I first Googled “How do I become a Canadian spy” in July 2005. I was living in London, U.K. working in finance when a bus and several subway stations had just been blown up by domestic homegrown terrorists only a few blocks from my office. Fifty-two people were killed and 770 were injured. Just four years earlier when two passenger planes hit the Twin Towers murdering nearly 3,000, I was a senior at Brown University in Rhode Island. This was followed by terrorists killing 191 civilians on a Madrid train. For those who don’t remember this time period, it was the age of terrorism. It was an age where not only did you know what the threat was, but it felt very real and dangerously close.

So, I signed up to be an intelligence officer with the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and joined the Canadian Forces Infantry Reserves with the Queens Own Rifles of Canada. I became part of a generation of young, idealistic Canadians who, as one of my former colleagues put it, “ran away and joined the circus.” We wanted to serve Canada and really weren’t all that sure what that meant or how to do it. If I’m honest, my first Google search was actually “Does Canada have spies?”

I would go on to spend nearly a decade serving in both organizations, leaving in 2016. Looking back, I am extremely proud of where I worked, what we accomplished, and the important work my former colleagues continue to do to keep Canada and Canadians safe. I was able to share some of this in my memoir, but most of it will always be a secret.

When I wore my army uniform in public, people used to walk up to me and thank me for my service. But my military career was mostly confined to parade nights at the armoury and the occasional weekend exercise in rural Ontario. It was while wearing my intelligence officer uniform (a generic button-down shirt and navy blue blazer) that I got to do the cool spy stuff that no one would ever know about or thank me publicly for.

Working long hours, dealing with stressful cases, and then lying to everyone I knew about what I was up to was a challenge. Occasionally you’d get a rah-rah speech from CSIS management saying things like, “The powers that be [the politicians in power] really appreciate everything you’re doing. They were so impressed with the information you were able to collect and you are making a real difference in the safety of our country.” It was a thankless job in many ways, but we did it because we believed we were making a difference.

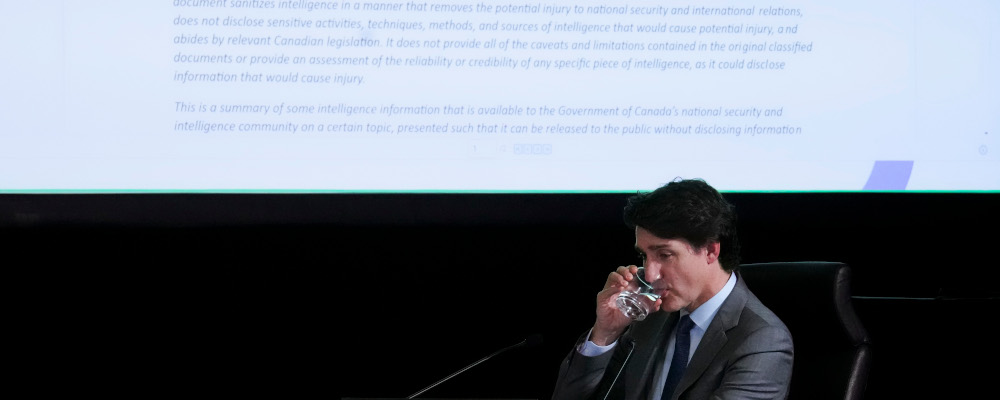

Today, I am not sure how any executive at CSIS will be able to stand up and give that speech with a straight face after watching Prime Minister Trudeau and senior officials at the foreign interference inquiry hearings say under oath, repeatedly, that they don’t often read CSIS briefs. That they take our intelligence with a huge grain of salt. That they don’t think our findings are worth following up on.

“There is a certain degree of—I would not say skepticism—but of critical thought that must be applied to any information collected by our security and intelligence services,” explained Prime Minister Trudeau.

The reason this is a major problem is not the hurt feelings of former spies, but what it reveals about the government’s attitude towards its spy agency and perhaps the wider public’s views on security. It’s an attitude that poses problems for the future security of Canada. There has always been a naiveté and complacency about the threats we face in an increasingly dangerous world. Canadians just don’t think much about our security. There is a general attitude of: “What does anyone want with us?” The lack of pressure the public is applying to government to fund our military in recent years may be a good illustration of this.

The reality is that our national security is not an accident. It is the result of thousands of men and women in our intelligence community, military, law enforcement, and corporate security, getting up each day and going to work. The safety we enjoy is on some level proof that the system is working. This also means our security is not guaranteed to continue. I believe Canada has been able to get by on the sacrifices of the few men and women who do these jobs, and that our political leadership, despite a lack of political pressure, has taken generally this threat seriously. Unfortunately, I fear that as the threats we face become more nuanced, those we entrust with our safety are increasingly unwilling or not sufficiently empowered to protect us.

The CSIS mandate is to collect, analyse, and advise government on threats to the security of Canada. There are four main threats: espionage and sabotage, foreign interference, terrorism, and subversion. It was my job to be a “collector” of information. As an intelligence officer for a domestic security service in the post-9/11 days, I was in the coffee and conversation business. I would often knock on doors 20 minutes from where I grew up, asking people for information and help with my national security investigation.

Back then when we tackled enemies like the 2006 Toronto 18 terrorists and the 2013 Via Rail derailment plot, it was a pretty straightforward job. We didn’t want to see the domestic attacks we saw around the world happen here at home. They were tangible threats we could see and easily explain at those doorsteps.

The threats CSIS is being asked to monitor today are far more nuanced and less visible. My colleagues and I used to worry about bombs going off in capital cities, but now an act of terrorism could be someone hacking into a water treatment plant to change chemical levels. In my day, foreign interference was honey traps and the attempted blackmail of elected officials. Now, we are uncovering potential state-sponsored misinformation campaigns during elections. Espionage and sabotage are rampant in the theft of IP and the hacking of companies. These threats are far less tangible and often difficult to attribute to a single source. Often we’re left with no easy answers to mitigate the risk.

Meanwhile, during this period when threats are evolving, our security apparatus is left to contend with a political leadership that is hesitant to listen to our warnings and seemingly content with avoiding having to deal with them.

Recently the government announced legislation to counter the threat of foreign interference, including expanding CSIS powers and a foreign agent registry. While many will be applauding these actions, I can’t help but think back to how this all began and what it took to finally get government to act. The public inquiry was the result of political pressure caused by the leaking of sensitive information to the media on the growing threats and their continued inaction on foreign interference. Leaking is wrong. It’s also not done lightly. It is a symptom of an intelligence service that felt its reports and advice were not being dealt with appropriately. I hope this is a wake-up call because it’s a terrible way to make national security policy.

I worry about what all of this means for Canadian security. What has this complacency meant for the next generation of army reservists and intelligence officer recruits?

In 2024, what is prompting their Google searches before submitting a job application to CSIS? And what are they going to encounter if they get there? In my time working for the intelligence service, it was a growing organization capitalizing off of a strong mandate, an army of bright-eyed recruits, and a risk-tolerant executive. Today, I fear that, at a time when their job is more difficult than ever, we may be losing our will to support those who are working to keep us safe. This is a dangerous direction to be going in.

Recommended for You

‘Putin has no intention of stopping this war’: Sir Bill Browder on three years of war in Ukraine and how Russia is evading sanctions

The Weekly Wrap: The Liberals must abandon their internet regulation agenda

‘This is going to take a carefully executed strategy’: Ann Fitz-Gerald on whether Canada will ever spend 5 percent of its GDP on defence

DeepDive: It’s time to end the boom-and-bust cycle of Canadian shipbuilding