Last week, a lot of eastern Canadian casual politicos woke up to what’s been going on in British Columbia. Let’s play some catch-up. Only nine months ago, British Columbia’s Conservative Party held one seat in the legislature and was polling at 16 percent. Not long before that—well, they were a bit of a joke.

The provincial Conservatives had a niche, certainly, but they weren’t a party that was contending for power. They were a place for right-wing British Columbians to park their vote when they felt that the centre-right brokerage BC Liberal Party wasn’t doing enough for the conservatives in its electoral coalition. Which was rarely required, because until recently, the BC Liberals did do a fair bit for the conservatives in their electoral coalition. So, the BC Conservatives remained on the fringe. Particularly when BC Liberal leaders could make the argument that their coalition had to hold together to block the NDP from taking power.

Then the NDP did take power. First through an agreement with the Greens, and then with a majority government of its own. And up until very recently, a huge number of British Columbians decided the NDP weren’t so radical after all. So, what became of the BC Liberal proposition? As, at first, the NDP showed the province they could be in favour of natural resource extraction, be reasonable stewards of the economy, and resist the excesses of trendy progressive social policy, the BC Liberals struggled to present a contrasting alternative, and in time, to articulate a raison d’être.

Then COVID hit, and the floundering BC Liberals made two very grave errors. They renamed the party to BC United, a branding faux pas that many others have dissected and I won’t dwell on here because I think the other misstep is even more important: they banned Aaron Gun from running in their party’s leadership race.

When Gunn sought to put his name forward to run for the BC Liberals, he had already made a name for himself as a cutting critic of the growing disorder and chaos in B.C. cities. Because while John Horgan had initially resisted the pull of progressive social policy, in time the provincial NDP, their municipal counterparts, and the public service apparatus of the region did fall prey to unwise, experimental policies, particularly related to decriminalization and drug policy. British Columbians were growing first impatient then angry at the lawlessness, addiction, death, and disorder. This as the cost-of-living crisis was growing more acute and the price of housing worse in Vancouver than anywhere else in Canada. And not only did Gunn have a strong message calling for change, he had the social media savvy to build a big audience and the storytelling prowess to channel people’s anger toward action. Sound familiar? Yeah, it did to Pierre Poilievre too.

Gunn didn’t have to decide to put his name on a ballot. He could have continued to monetize his online influence. He saw an opportunity to translate his message into political action, though, and he was willing to put his money where his mouth was. But just as the NDP had fallen prey to trendy social progressivism, so had what remained of the BC Liberal party establishment. The powers that be determined that Gunn shouldn’t be eligible to run in their leadership. They barred him from running, and in so doing, sent a message, loud and clear to young, energized activists—many of them new to politics and conservatism and eager to help—that they weren’t wanted in the BC Liberal party.

From that point on, exacerbated by the rebrand, BC United lost traction and relevance, finding themselves squished into a very narrow band in the middle of the political spectrum, representing Vancouver business interests and not much else. All the while, public resentment has fueled populism, forcing political parties to find ways to resonate with working-class Canadians.

In the meantime, Gunn got himself nominated as a federal Conservative candidate, giving the party a strong chance at winning his north Vancouver Island seat and setting himself up to be a future star in a governing Conservative caucus in Ottawa.

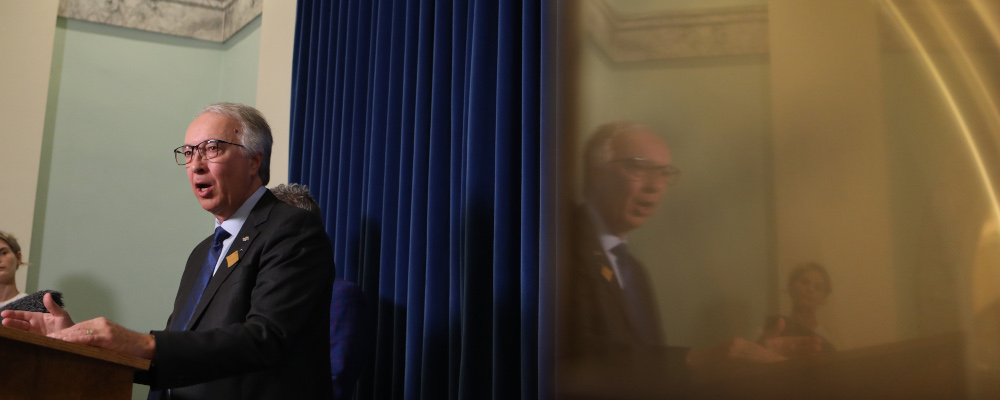

Enter John Rustad and the BC Conservatives, now sitting somewhere between 34 percent and 38 percent (to the NDP’s 40 percent) depending on the pollster. Five months out from an election campaign, the BC Conservatives have gone from a fringe party to contenders for government, and if not that, a strong opposition. This is an incredible political accomplishment.

But as with other right-wing populist movements, the commentariat has been quick to try to explain the success away. It’s true Rustad and his party are capitalizing on a very popular federal Conservative brand. But why assume that brand association will peel away? Yes, it’s possible some voters will clue into the difference between the provincial and federal parties during a writ period and thus choose not to lend their vote to the provincial party. But it’s equally possible that voters will simply see in the BC Conservatives much of what they like about the federal Conservatives. Namely, change.

That’s because Rustad has not sat back and let others do the work for him. He spoke up on issues where BC United either couldn’t or wouldn’t. On the carbon tax, gender identity, drugs and decriminalization, and Indigenous reconciliation, Rustad has staked out ground Kevin Falcon has effectively conceded. And when BC United has tried to jump on an issue, it’s been too little too late, proving to voters that if they want change, they should go with the real deal.

All of this is why last week’s frenzied coverage of rumours about merger negotiations sounded a lot more like the wishful thinking of the B.C. business community than it did a pre-election likelihood. After all, why would Rustad consider a merger? Even the mainstream media is conceding that his polling position has moved from flash in the pan to serious trend. He’s nominated young, diverse candidates across the province, and NDP Premier David Eby is treating him like his primary opponent (one who he is concerned is gaining on him).

If Rustad and the BC Conservatives can stick to the key issues that British Columbians care about and the NDP can’t match them on, improve their fundraising outcomes by converting messaging on those issues into effective small-donor appeals, and organize a professional ground game to drive voter identification and get out their vote on election day, they stand the chance of reducing BC United’s vote and seat count even further while increasing their own. It’s hard to imagine they won’t either form government or take up the mantle of a strong opposition to a weakened NDP government.

Rustad has nothing to gain from negotiating with a party he’s crushing in the polls. Especially because so much of his party’s appeal comes from their rejection of establishment thinking. It’s not that the goal shouldn’t eventually be for the Right to be united again in British Columbia. It’s just that if and when there are negotiations to do so, Rustad and the BC Conservatives better be darn sure they’re taken entirely on their terms. They’ve earned it.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

Ginny Roth: How vacant liberal nationalism left Canada worse off than George Grant even imagined

Peter Menzies: Justin Trudeau’s legislative legacy is still haunting the Liberals

‘Our role is to ask uncomfortable questions’: The Full Press on why transgender issues are the third rail of Canadian journalism