In each EconMinute, Business Council of Alberta economist Alicia Planincic seeks to better understand the economic issues that matter to Canadians: from business competitiveness to housing affordability to living standards and our country’s lack of productivity growth. She strives to answer burning questions, tackle misconceptions, and uncover what’s really going on in the Canadian economy.

The labour market is an important sign of the health of Canada’s economy. Recently, it has been described as cooling off, as the unemployment rate increased slightly in May. But, because most experts see this as a good sign, giving the Bank of Canada permission to continue to lower interest rates, hardly anyone has raised alarm bells. In fact, talk of a recession, and angsty Google searches, have all but fallen away.

But should we be worried?

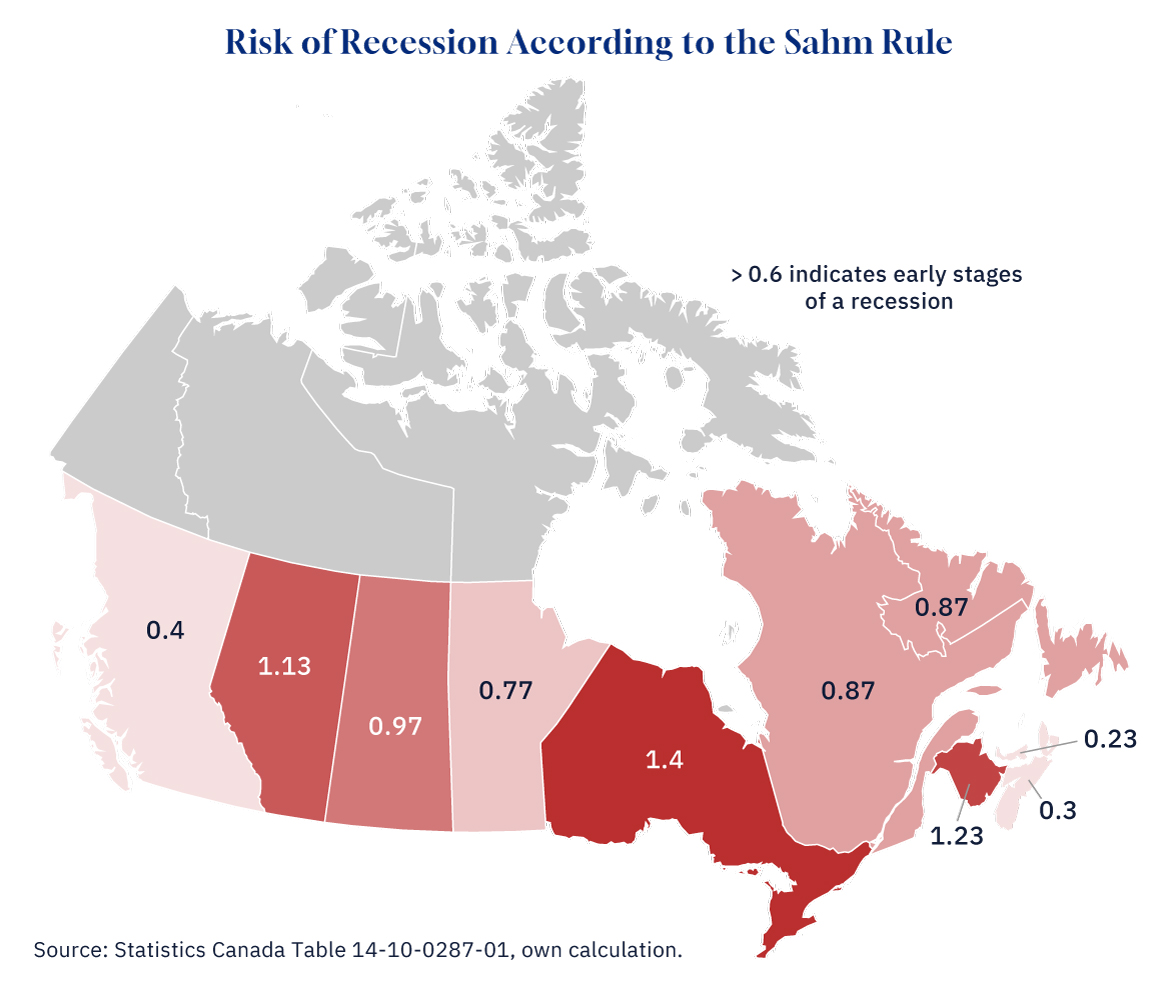

U.S. economist Claudia Sahm created a rule of thumb—called the Sahm Rule—for when an increase in unemployment is more than just a minor adjustment but instead signals an economic downturn. The rule goes that if the current unemployment rate is significantly higher than the lowest rate seen over the past year, it means we’re in the early stages of a recession. In Canada, this trigger point is around 0.6, and using the rule retroactively has only ever incorrectly signaled a recession one time.

Unfortunately for Canada, the Sahm Rule suggests that, at 0.97, the recession warning light is blinking red.

And, though there are some regional differences, this warning sign is largely flashing across provinces. Specifically, provincial estimates show:

- Seven provinces are signaling the early stages of a recession.

- The signal is most alarming in Ontario, where the number sits at 1.4.

- Interestingly, Alberta—with the fastest population growth and the highest expected economic growth this year—comes in second at 1.13.

- Meanwhile, a few provinces have seen an increase in unemployment but are still below the trigger point: B.C., Nova Scotia, and P.E.I.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Month to month, it can be easy to overlook just how much the labour market has weakened. But as the Sahm Rule makes clear, today’s labour market is not the same place of plentiful job opportunity it once was, and in most provinces the scale of the turnaround is concerning. While a recession would certainly give the Bank of Canada permission to further lower rates, cheaper debt hardly beats having a job.

That said, Sahm herself has emphasized that the rule can be broken and, in fact, already has. So, while it’s important not to dismiss the current turnaround in the labour market as simply expected or necessary, we’d also be wise to consider if or why this rule no longer holds.

This post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.

Recommended for You

The Notebook by Theo Argitis: Carney’s One Big Beautiful Tax Cut, and fresh budget lessons from the U.K.

Rudyard Griffiths and Sean Speer: The fiscal hangover from the One Big Beautiful Bill hits Canada

Lucy Hargreaves: Canada needs builders, not bystanders

Need to Know: Mark Carney’s digital services tax disaster