DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

Introduction

Canadians are losing their trust in the media. According to a report from the Reuters Institute at the University of Oxford, overall trust in the media among the Canadian population has fallen from 55 percent in 2016 to 40 percent in 2023. Among English-speaking Canadians, trust in the news is even lower with just 37 percent saying they trust the media in 2023.

The decline in trust comes at a time when the federal government is increasingly intervening to support major incumbent firms in the Canadian media landscape like The Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star and Postmedia. These measures include subsidies supporting the payrolls of qualified private news media, mandating Google to pay $100 million annually to support the journalism industry, and a tax credit for news subscriptions, among other measures. At this point, estimates suggest that there could be as much as a 50 percent subsidy on journalist salaries up to $85,000 per year.

Amid already declining trust in the news media, there are growing questions about how government support for the industry is perceived by Canadians and to what extent this may influence trust. Likewise, further effort is needed to decompose trust along various social cleavages (including education levels and political preferences) to better understand variation in media trust among Canadians.

To this end, The Hub has partnered with Public Square Research to conduct polling on the public’s trust in the news media across the country and its views on the government subsidization of the industry. This DeepDive presents the results of this poll and discusses the potential threat that government backing of the media might pose to the news media’s already deteriorating relationship with the Canadian public. It also puts forward some alternative policy options that aim to minimize the scope of government intervention by following consumer behaviour in the market.

Survey methodology

The “Trust in News Media” survey project is focused on the trust relationship with news media in Canada. It was designed with two main objectives.

The first objective was to grasp overall perceptions of news media in Canada that may contribute to and/or undermine existing trust in news. The second objective was to gauge public awareness of recent federal legislation that will fund news organizations, as well as the overall support for public funding of journalists and journalism.

The questionnaire was designed by Public Square Research in partnership with The Hub. The survey included twenty-four discrete questions, with additional demographics. The questions covered perceptions of news media, awareness, and support for government legislation, as well as both positive and negative arguments underpinning government legislation, and the potential impact of legislation on trust in the media.

The online survey was conducted in both French and English and included 1,500 adult Canadians, which were reflective of the gender, age, and regional composition of Canada. The survey was conducted between May 28 and June 2, 2024. While online surveys cannot be assigned a margin of error, the corresponding margin of error for a probability sample of this size is +/- 2.5 percentage points, 19 times out of 20. The margin of error will be larger when looking at sub-populations in crosstabulation.

Impressions of the media

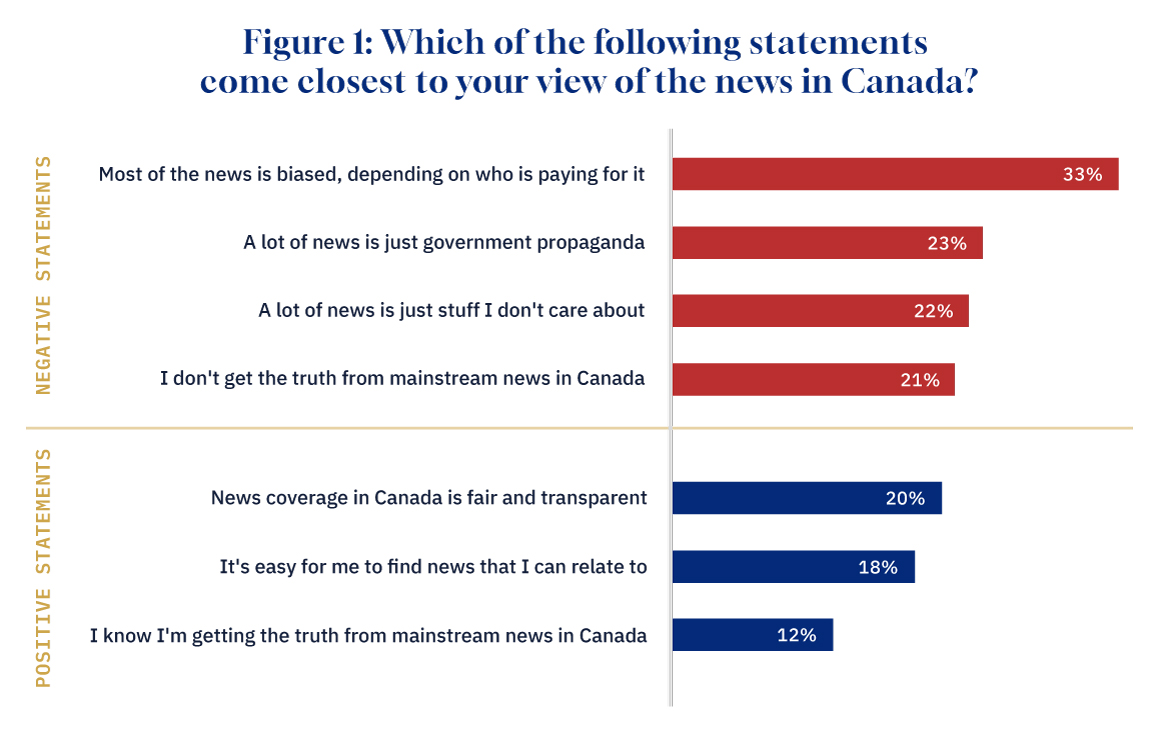

Survey respondents were given a list of positive and corresponding negative statements about the news in random order and asked to select the statements which came closest to their view of the media. This question was designed to isolate positive and negative perceptions, and rank which specific qualities have the greatest impact on overall perceptions of the news.

As seen in Figure 1, not surprisingly, negative statements were selected more often, with one-in-three saying that there is a lot of bias in the news—depending on who is paying for it. One in four say a lot of news is just government propaganda, and one-in-five say that news is stuff they don’t care about (22 percent) or that they don’t think they get the truth from mainstream news in Canada (21 percent).

By contrast, positive judgements were selected by fewer, with two in ten or less saying the news was fair and transparent (20 percent) or easy to relate to (18 percent), and only twelve percent saying they were getting truth from the news.

Q2. Which of the following statements come closest to your view of the news in Canada these days? Choose up to 5 that best represent your view. N=1529.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Impressions of the media by party support

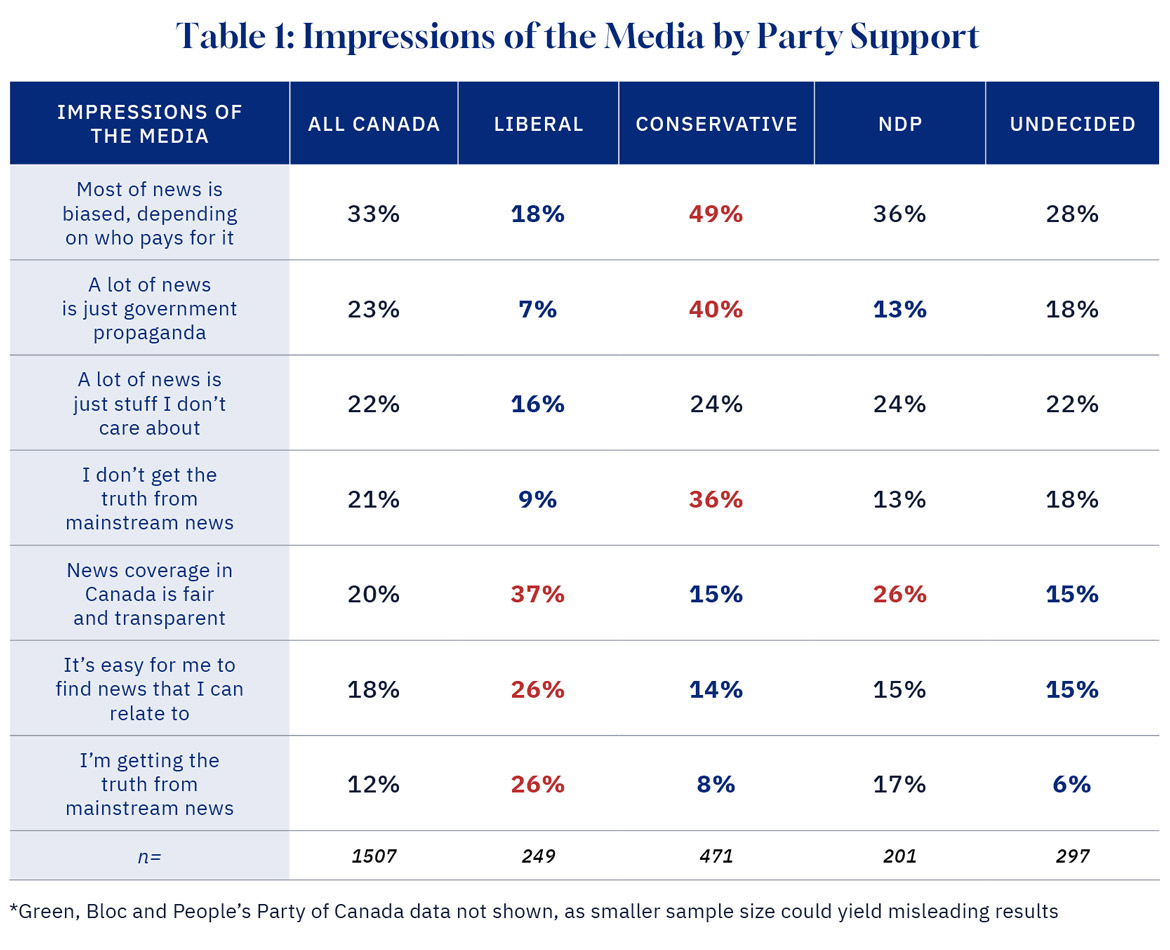

Reviewing the same questions through a partisan lens we see a distinct pattern emerge. Liberal Party supporters are much less likely to agree with negative statements, and much more likely to agree with the positive statements about the news media (see Table 1).

Conversely, Conservative Party supporters are much more likely to hold negative views of the media and are less likely to hold positive views, with half of Conservative Party supporters saying that the news is biased, depending on who is paying for it, and four in ten saying that a lot of news is just government propaganda, and more than a third (36 percent), saying that they don’t get the truth from mainstream news. NDP, Green,* and Bloc* supporters fall more closely to the average, with a few exceptions.

Q2. Which of the following statements come closest to your view of the news in Canada these days? Choose up to 5 that best represent your view. N=1529.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Very few aware of government funding journalists’ salaries

In order to understand the public attitudes about the public funding of news media, we need to first gauge awareness of the broader legislation. When asked, we found that few Canadians said they were actually aware of the details of the government’s direct and indirect support for the industry, including specifically through the Online News Act (Bill C-18).

In fact, only four percent said they were following the legislation closely, and roughly another quarter (24 percent) said they have heard of it, but don’t know the details. That leaves close to three-quarters of the Canadian public unaware of the legislation, or details of the legalisation (data not shown). Consequently, few would have known about the government’s intention to defray the costs of journalists and journalism at all.

Few supportive of government funding journalists’ salaries

Importantly though, when asked how supportive they would be of government subsidies for the salaries of private news organizations, such as the Globe and Mail, Toronto Star, Toronto Sun, or the National Post, only four percent said they were very supportive, and another twenty-six percent said they were somewhat supportive. That leaves a strong majority of Canadians—seven in ten—not very supportive, or not supportive at all.

Young people and those who are university educated are most likely to be supportive, and older Canadians (sixty-five years of age or older) are most likely to be not supportive at all.

Once again, we find a distinct partisan split on this issue, with Liberal and Green Party supporters more likely to be supportive (44, and 41 percent respectively), compared with only two-in-ten Conservative Party supporters. Conservatives are also most likely to be not supportive at all (47 percent).

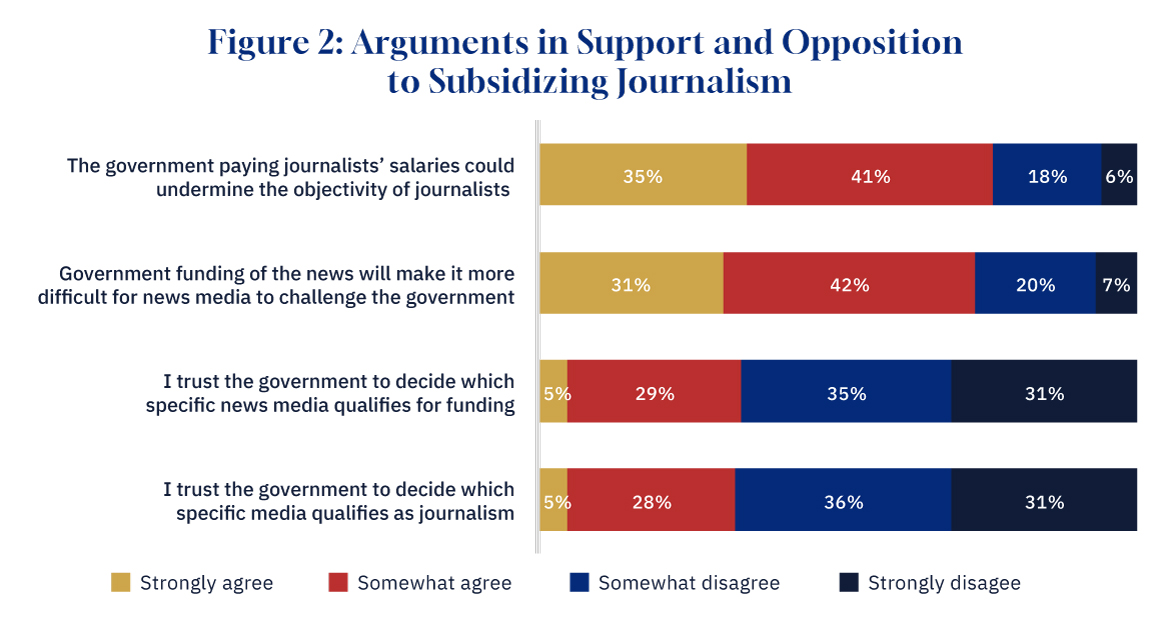

Why Canadians aren’t supportive of subsidizing the news

Concerns about the growing subsidisation of news among the public centred on issues of objectivity and the ability of the media to perform a key function in holding governments to account (see Figure 2). More than three-quarters (76 percent) of Canadians agreed that the government subsidizing journalists’ salaries could negatively impact journalist objectivity. Likewise, almost three-quarters (73 percent) of Canadians agreed that if the government was funding the news, this would make it more difficult for news media to hold government to account, a core public interest function of the media.

Canadians were also concerned about the capacity of government to subsidize private news media in a fair and transparent manner. Specifically, two-thirds (66 percent) of Canadians felt that they wouldn’t trust the government to decide which specific news organizations qualified for funding and two-thirds (67 percent) also felt that they wouldn’t trust the government to define which specific media qualifies as journalism.

Q3. How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the government and the news media, and the funding of news? N=1529.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

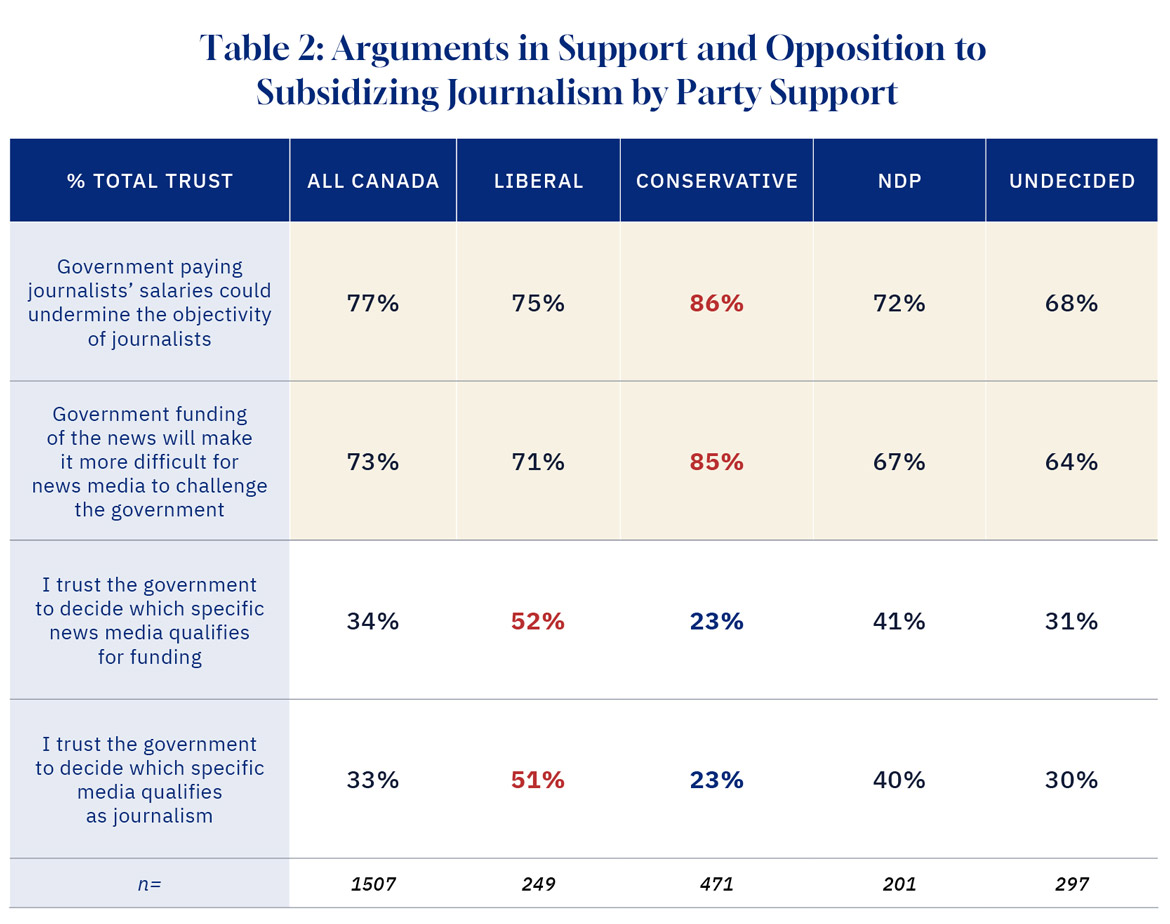

Interestingly, while there was partisan disagreement over support for government funding news media, there is greater agreement among Canadians of different party affiliations in terms of concerns about the effect of government subsidies on journalist objectivity (see Table 2). Over 70 percent of supporters of all major political parties agree that having the government paying journalists’ salaries could undermine journalist objectivity, ranging from a high of 86 percent of Conservative supporters to 72 percent of NDP supporters. Similar strong cross-party majorities are also concerned with how government subsidization will impact the ability of news media to challenge government.

Where there is more partisan disagreement is in terms of whether supporters of different political parties trust the government to decide who receives the funding and which organizations are deemed sufficiently journalistic. In this instance, a slight majority of Liberal supporters trust the government to make these decisions, while on the other side, less than one-quarter (23 percent) of Conservative supporters trust the government to make those decisions.

Q3. How much do you agree or disagree with the following statements about the government and the news media, and the funding of news? N=1529.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

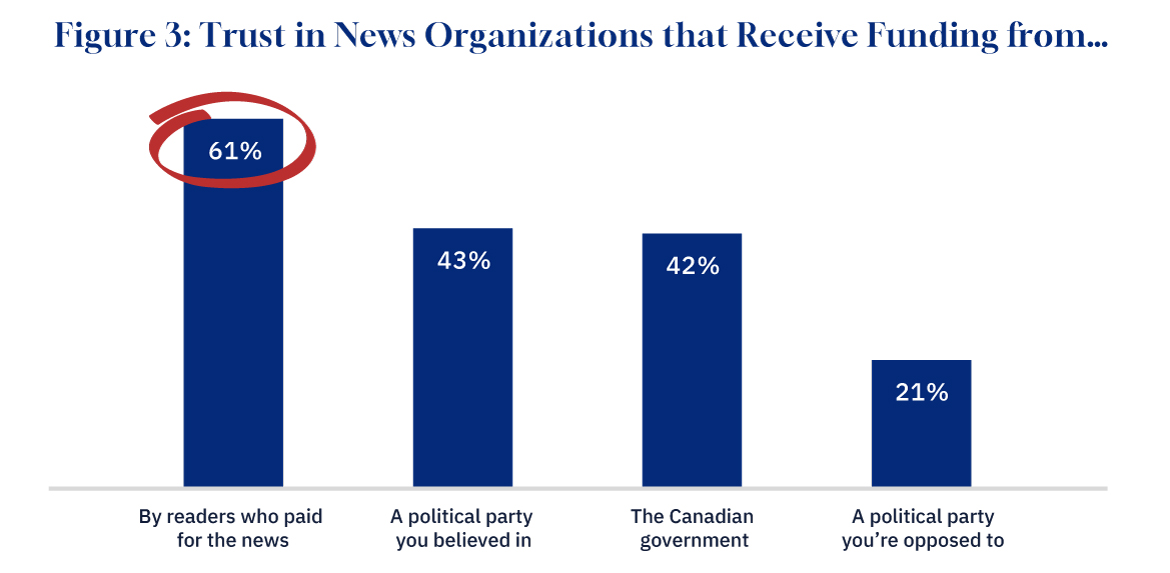

Trust in news organizations that receive funding

Finally, we turn to an evaluation of Canadian trust in the media by different funding models in Figure 3. Overall, trust in the media is highest if the media organization funding is based on readers paying for the news. Indeed, three in five Canadians (61 percent) trust media that is funded by readers. This is in comparison to two in five (42 percent) of Canadians trusting media that is funded by the Canadian government, while only one in five Canadians (21 percent) trust news organizations that receive funding from a political party that they’re opposed to. This result further highlights the risk of how funding from partisan governments could further erode trust in news media, which is already in decline.

Q4. How much would you trust a news organization that was receiving funding from any of the following; N=1529.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Key takeaways

Public trust in the Canadian news media is declining. As of 2023, according to research from the University of Oxford, only two-in-five Canadians have trust in the news media. Polling by The Hub in partnership with Public Square Research provides some indication of why trust is eroding and how growing government subsidies of journalist salaries may further impact this slide. For instance, Canadians are concerned about perceived bias in the news media, fairness and transparency in news coverage, as well as the relatability of news coverage. Moreover, most Canadians are unaware of recent policy initiatives that see government funding journalist salaries, and seven-in-ten Canadians are not supportive of these policies, with concerns including that government subsidization will negatively impact journalistic objectivity and the ability of news media to hold governments to account.

Our research also illuminates a growing partisan dimension towards how Canadians view the news media. Liberal and Green Party supporters are more likely to be supportive of government subsidization of journalist salaries (44 and 41 percent respectively), compared with only two-in-ten Conservative supporters. However, there is some partisan agreement in terms of concerns regarding the negative effect of government subsidies on journalistic objectivity and government accountability. Regardless of party support, at least seven-in-ten Canadians share these concerns.

Taking the issue of declining trust in news media seriously and recognizing the democratic importance of a free and independent press to hold the powerful (including government) accountable, it’s worrisome that government subsidies and partisan perceptions could erode this trust further. The poll results highlight the potential importance of initiatives like the Ottawa Declaration on Canadian Journalism to establish the independence of emerging news media in an attempt to rebuild the trust of the Canadian public.

Moreover, the federal government should consider the impact of current and future subsidization initiatives on public trust in the news media. It should also recognize the unintended consequences of the further erosion of public perceptions of legitimacy. As such, the government may wish to consider policy reforms that could mitigate the concerns that the Canadian public has (see below) by creating a stronger market role for any public programs that support the industry.

Ultimately, a key takeaway from this DeepDive is that trust in the news media is highest when journalism is funded by readers.

A man reads the final print edition of the French language newspaper La Presse at a coffee shop in Vaudreuil-Dorion, west of Montreal, Saturday, December 30, 2017. Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press.

Policy proposals for reforming government support of the news media

In light of the above polling, one of us (Taylor Jackson) has a series of policy proposals that could reform government support for the industry and stop the further slide of Canadians’ trust in media.

1. Tax credits for digital news subscriptions—let the money follow the reader

The federal government’s digital news subscription tax credit is presently a non-refundable tax credit of 15 percent on up to $500 in annual subscription spending. France’s equivalent tax credit is 30 percent. Canada’s political tax credit is more generous than both—it can be up to 75 percent on the first $400 in donations. The government may consider expanding the generosity of the digital subscription tax credits to bring it closer in line with France or the political donations tax credit. The government could also make the tax credit refundable so that Canadians receive the benefit independent of whether they have taxes owing. A key virtue of the tax credit is that public subsidies follow consumers’ market behaviour. It therefore creates a market test—something which is missing from the current subsidy model.

2. Define news journalism as a charitable activity and allow charitable incorporation of new groups

Journalism isn’t presently an eligible charitable activity under the Income Tax Act. The government has sought to get around this issue by creating a whole new class of organizations called Registered Journalism Organizations that have the ability to issue charitable tax receipts. Few journalistic outlets have opted into the new model because of its onerous approval process and overall complexity. A simpler approach would be to make journalism a charitable activity. News media organizations could then be able to avail themselves of the benefits of charitable status. Public subsidies (like in the case of option one) would follow consumer behaviour and flow to individuals rather than news media outlets themselves.

3. Reform the CBC and make it a local news wire service

The strongest case for policy intervention in the industry may be to support local journalism where one could argue there is a genuine market failure. The problem is that the CBC is presently solving this issue. Its footprint only extends to about 40 cities and communities which mostly includes provincial capitals and other key population centres. Although it has added to its local journalism capacity in recent years, it would require a far more fundamental reconfiguration of the CBC’s staffing and operations to reposition the broadcaster as primarily focused on delivering news and information for smaller markets. One such model would be to transition it to a Canadian Press-style wire service, with journalists in communities across the country focused on reporting on local issues.