On Friday, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre pre-empted the vacillating Trudeau government by rightly calling for import tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles as well as other manufactured goods. His case for tariffs stands in sharp contrast with a recent Globe and Mail op-ed which argued in favour of importing Chinese EVs on the grounds that the risk to Canadian automakers is “exaggerated.” Poilievre is right and the op-ed writers are wrong.

Let’s go through to the heart of the central claim made in the Globe and Mail. Are Chinese-made EVs cheaper than those made in North America? Yes. But the authors overlook the unfair advantages that Chinese firms enjoy. They briefly nod to forced labour but ignore the various other ways that Beijing has heavily subsidized the Chinese EV sector to undercut global competitors, including forcing technology sharing, limiting foreign competition, and pouring public funds into the industry since 2009 to accomplish the industrial goals as laid out in its 14th Five-Year Plan.

Canadian firms should absolutely be expected to compete on market terms with companies from around the world. But what if companies aren’t operating according to market principles? In today’s era of “geoeconomics,” Canadian policymakers may need to step in to level the playing field. This is such a case.

Ottawa has started to recognize the nature of the problem here and began to consult on how to respond to the reality that “Chinese producers are generating a global oversupply” while benefiting from “unfair competition from China’s intentional, state-directed policy of overcapacity and lack of rigorous labour and environmental standards.” But the Trudeau government has moved too slowly.

Poilievre’s high-profile announcement is a sign that he recognizes that Beijing’s global strategy relies on using the excess capacity of domestic production to flood foreign markets and in so doing kneecap foreign auto industries. This is the continuation and evolution of a pattern of behaviour seen since 1989 in industries as varied as textiles, plastics, vaccines, mineral processing, and steel.

The excess auto production capacity of China is difficult to determine, but global estimates put it at anywhere between 5 million to 10 million cars per year. This level of surplus supply equals between a third and two-thirds of total North American car production in 2023, while EV sales in the U.S. have just passed 1.4 million in 2023. (Canada managed 275,000 in 2023).

This level of unfettered Chinese excess supply into the Canadian market would be disastrous to the southern Ontario auto industry. Automaking is one of the few value-adding industries that we have retained in the face of a massive loss of manufacturing jobs over the past decades.

Declining opportunities in auto manufacturing are yet another symptom of a real policy trade-off that has seen jobs sent overseas and diminishing opportunities at home for those who are left. From 2006 to 2016, there was a loss of over 216,000 manufacturing jobs in Ontario alone. Research suggests that something like half of these job losses may be attributable to the “China shock” of low-cost import penetration.

These job losses have big spillover effects. According to Statistics Canada, between 2000 and 2015, there was a 10 percent drop in full-time, full-year employment for men in southern Ontario, the cause of which the agency, by and large, ascribes to the decline in manufacturing.

A BYD ATTO 3 electric sports utility vehicle gets charged at a BYD dealership on April 4, 2023, in Yokohama near Tokyo. Eugene Hoshiko/AP Photo.

The same happened in the U.S., where employment and wages in sectors exposed to Chinese competition over the past three or four decades have fallen and never recovered. This should not be news to anyone. The hope of “retraining” and “reskilling” workers that we hear so often about all too often is nothing but a mirage, told to make ourselves feel as though we are not denuding entire parts of the country and the affected population of their livelihood.

The challenge for policymakers here is determining when and in what cases to intervene to protect Canadian industry from unfair advantages that Chinese firms have. We must be able to judge what sectors are strategic and what constitutes state-driven advantages versus the normal vicissitudes of market competition.

The playing field should be generally level, which in the case of China, it is certainly not. We also need to recognize that in certain cases like semiconductors or vaccines, there are spillover benefits or strategic reasons why we want a domestic productive capacity.

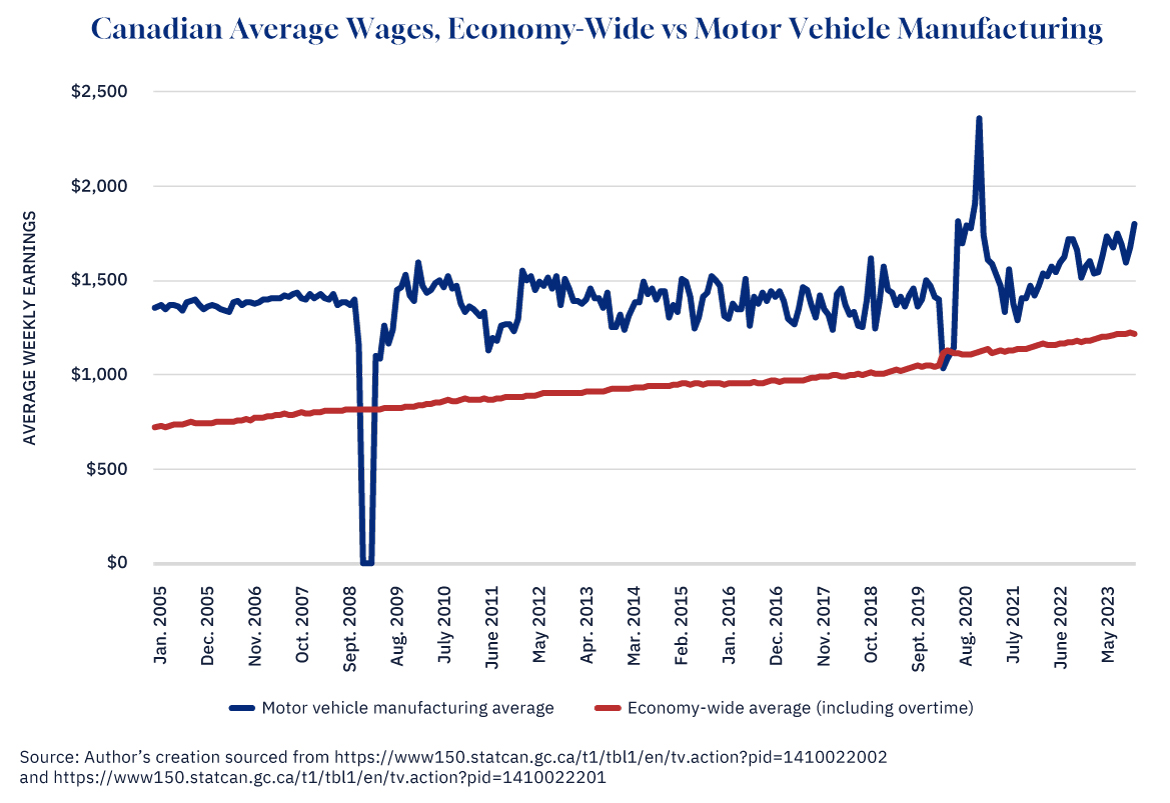

One can argue that the auto sector fits this description. Here, we have an established sector that provides direct employment for over 117,000 Canadians (and spinoff automotive jobs for 371,000 more), is one of the parts of the economy invested in research and development and value-added production that produces a quality (increasing technology-heavy) good that nearly everyone has use for. Wages in the auto sector have consistently been above the Canadian average, with the brief exception in 2009 during the Great Recession (see below).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

To consign this sector to a tsunami of Chinese state-supported companies bent on wreaking the same destruction that they’ve done to the rest of North American manufacturing is an exercise in economic nihilism. Will manufacturing still face headwinds? Yes, undoubtedly so. Automation, changing consumer tastes, and fair international competition are going to be major challenges for Canadian firms in the future. But our response to an incoming, state-supported flood from Beijing cannot be to shrug our shoulders and say that it makes no difference whether the sector lives or dies, or where our cars come from.

Further potential economic storms lurk ahead. As Chinese EV manufacturer BYD has looked to establish branch plants in Mexico, the American auto sector has already responded in force, calling for changes to CUSMA to consider the potential for backdoor sales in the U.S. While CUSMA does have provisions that could be used to prohibit Chinese vehicles made in China to be sold into the U.S. via Canada or Mexico, branch plants are a different beast. Washington is understandably very twitchy about this and will take cautions to ensure China does not reap advantages from CUSMA.

It would be much better for our two countries if Ottawa proactively tariffed Chinese EVs and avoided endangering our most important economic partnership over a potential branch plant. Averting an unnecessary confrontation with the U.S. that muddies the waters around CUSMA (especially given the deal is set to be renegotiated in 2026) is one area where American and Canadian interests solidly align. Clearing the decks and soothing the American auto industry (and their significant lobby power in Washington) is a wise way to smooth the renegotiation. But avoiding the fate of Europe should be our ultimate goal.

In Europe, the auto industry (dependent on China for high-end luxury auto sales) fears retaliatory tariffs from China should there be a strong tariff on consumer EV imports. This has limited the ability of the European Union, a bloc built on consensus, to find an effective way to respond, and Chinese EVs are starting to show up in force. This displacement will have the net result of dampening the native EU auto market, and even if there is a BYD branch plant set up in Hungary, it will not be sufficient to make up the difference. And once established, it will create vested interests, coopting domestic politicians and businesses, and further paralyze an EU policy response as the situation degrades.

None of this discounts the fact that EV sales are growing year-over-year, and will likely be the dominant vehicle type in the future. But that is even more reason that we should reject being led down a primrose path we have been down before with every other type of manufacturing that has come under Chinese pressure. Beijing does not share our values or play by our accepted rules of capitalist competition. It seeks once again to ensnare the West into dependency for another economically critical sector. We have woken up to this threat in vaccines, steel, and microchips. Why go down this path again when we already know the way it ends?