DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of Centre for Civic Engagement.

Anyone who pays any attention to economic policy debates in Canada knows that our productivity performance in recent years has been disappointing—and that’s putting it politely. Carolyn Rogers, the senior deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, put it more bluntly in a speech in March when she said that Canada faces a productivity “emergency” and it is “time to break the glass.”

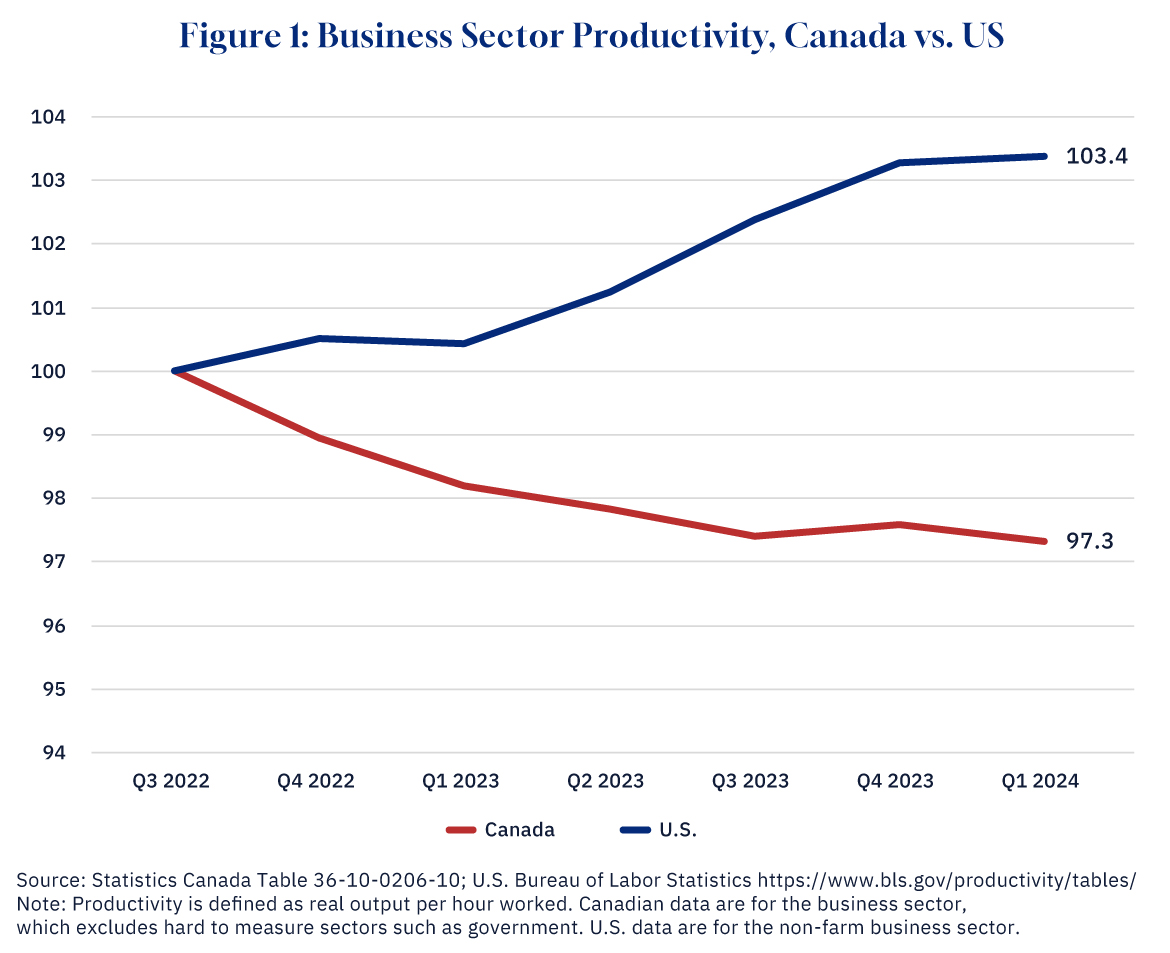

Not only is productivity—how much output each worker produces in an hour—not growing, but it is actually falling. As Figure 1 shows, Canadian productivity is lower now than it was in mid-2022 when the economy was coming out of COVID. Compare that to the United States, which has seen robust productivity growth since COVID and is now back to its pre-pandemic trend.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Canada’s poor productivity record comes with real costs for ordinary Canadians in the form of lower wages and living standards than in the U.S. The growing Canada-U.S. labour productivity gap is now 30 percent and that manifests itself in $20,000 less in GDP per capita for Canadians relative to Americans.

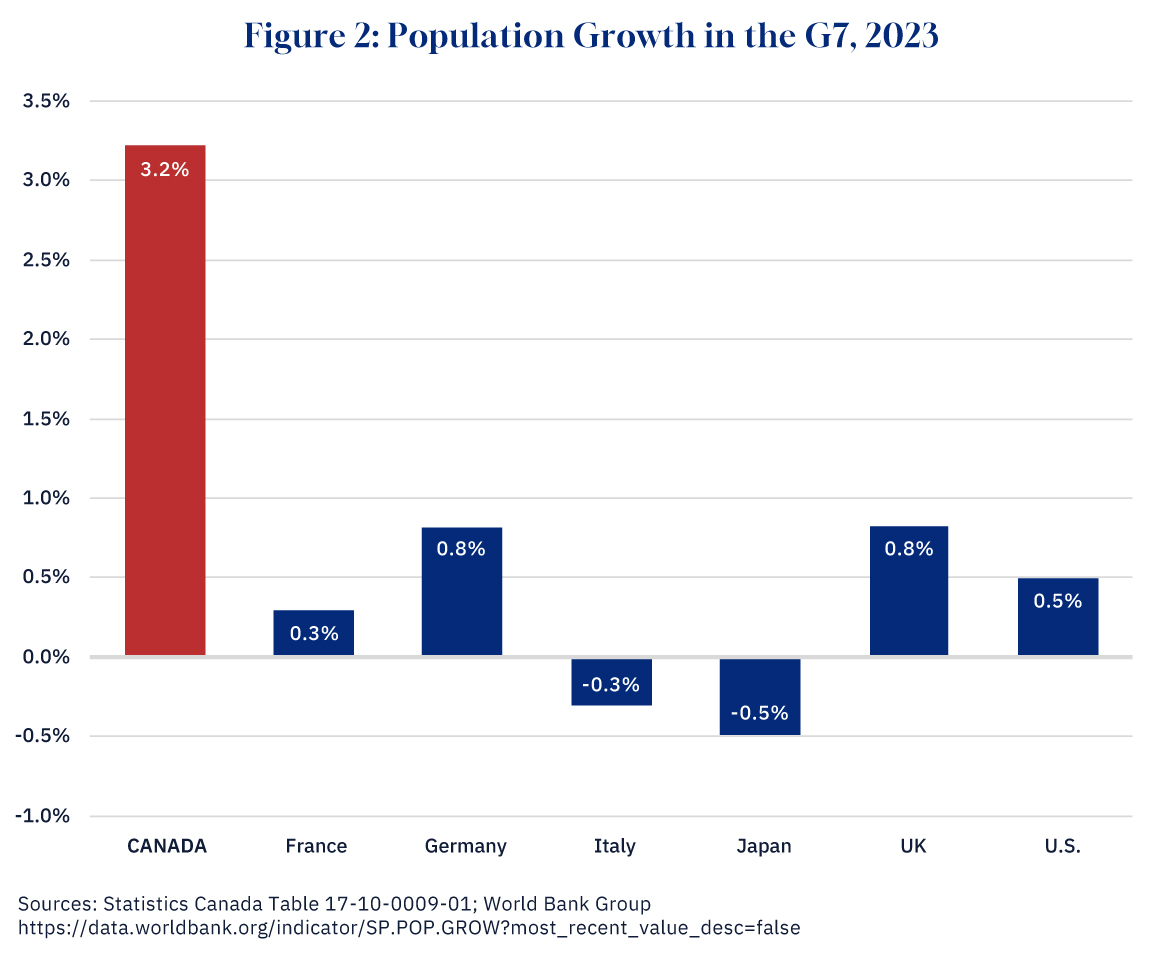

However, one area where Canada leads not just the U.S. but the developed world is population growth. As StatsCan reported in March, the Canadian population grew by 3.2 percent in 2023, blasting through the 40 million barrier to 40.8 million. This increase was the largest in percentage terms since 1957 when there was an influx of Hungarian refugees following the 1956 uprising. As Figure 2 shows, Canada’s population growth in 2023 was much higher than any other G7 country, much higher than the U.K. with 0.8 percent growth and the U.S. with 0.5 percent growth. Indeed, Canada’s population growth is more on a par with West African countries like Mali or Chad where women typically have five or six children.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

This surge in population did not come from women having more babies. As I have noted in an earlier Hub piece, Canada’s fertility rate reached a record low in 2023. Instead, 98 percent of Canada’s population growth came from immigration.

In this DeepDive we ask whether these two phenomena of falling productivity and rising immigration are connected. More specifically, has the surge in immigration had anything to do with Canada’s disappointing productivity performance?

What has driven the surge in immigration in Canada?

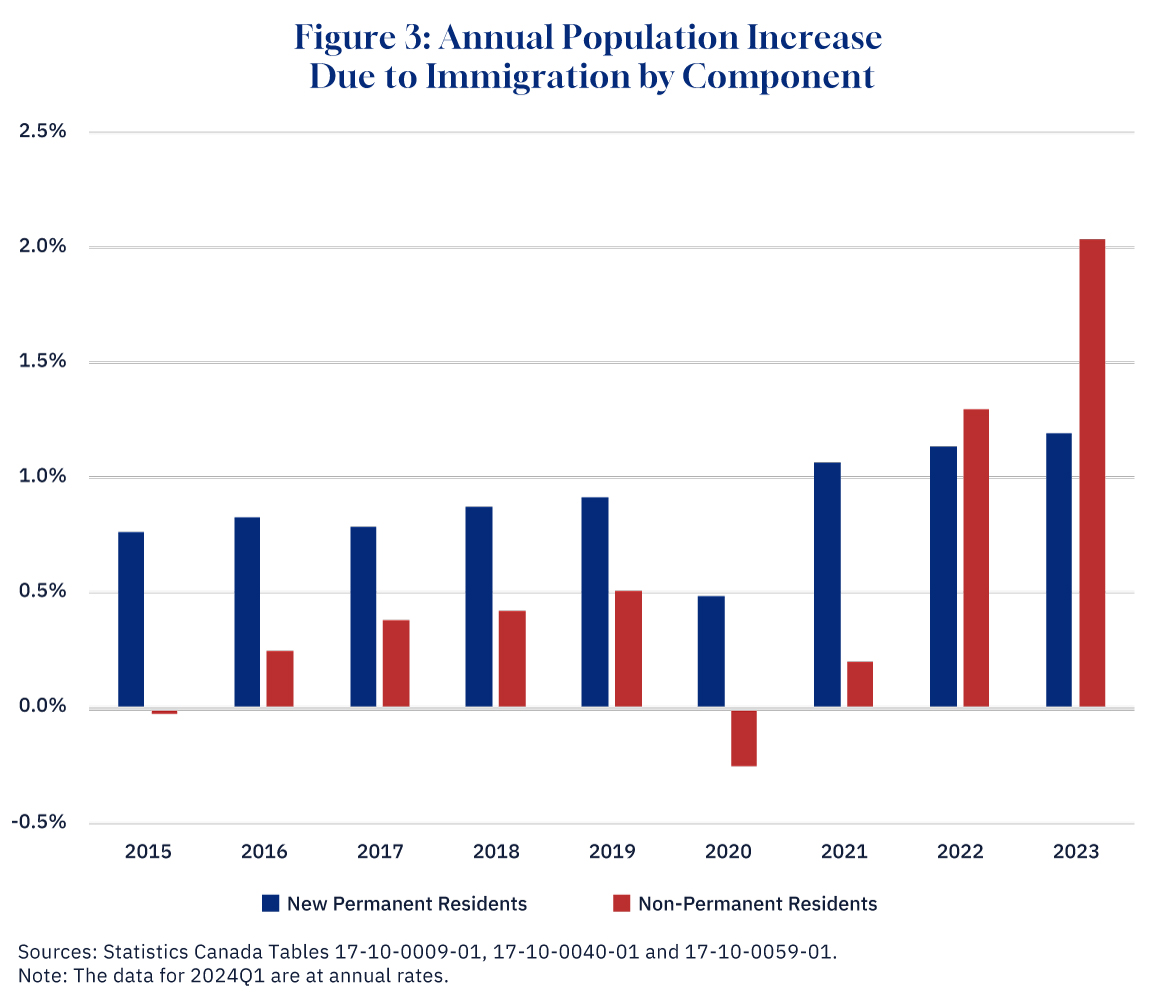

Let’s dive into the numbers. Figure 3 below shows the overall percentage increase in Canada’s population from immigration since 2015, the last year of the Harper government, divided up into two categories.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The first is new permanent residents, who have been granted the right to live and work permanently in Canada. Often these immigrants will have been living abroad before obtaining permanent residence status, although in some cases they might have already been in Canada as temporary residents. About 40 percent of new permanent residents are selected on economic criteria; however, most are not: they are either family members of economic applicants (20 percent), family members of those who have already immigrated to Canada (20 percent), or refugees (15 percent).

As the chart shows, the number of new permanent residents has been growing. In 2015 they contributed 0.7 percentage points to Canada’s overall population growth of 0.8 percent; by 2023 they contributed 1.2 percentage points to overall population growth of 3.2 percent.

However, permanent residents have been surpassed as a contributor to population growth by the other category of immigrants: non-permanent residents (NPRs). There were very few in this category in 2015, but their numbers have grown rapidly: by 2023 they contributed 2.0 percentage points to population growth, so that almost two-thirds of Canada’s overall population growth was accounted for by NPRs.

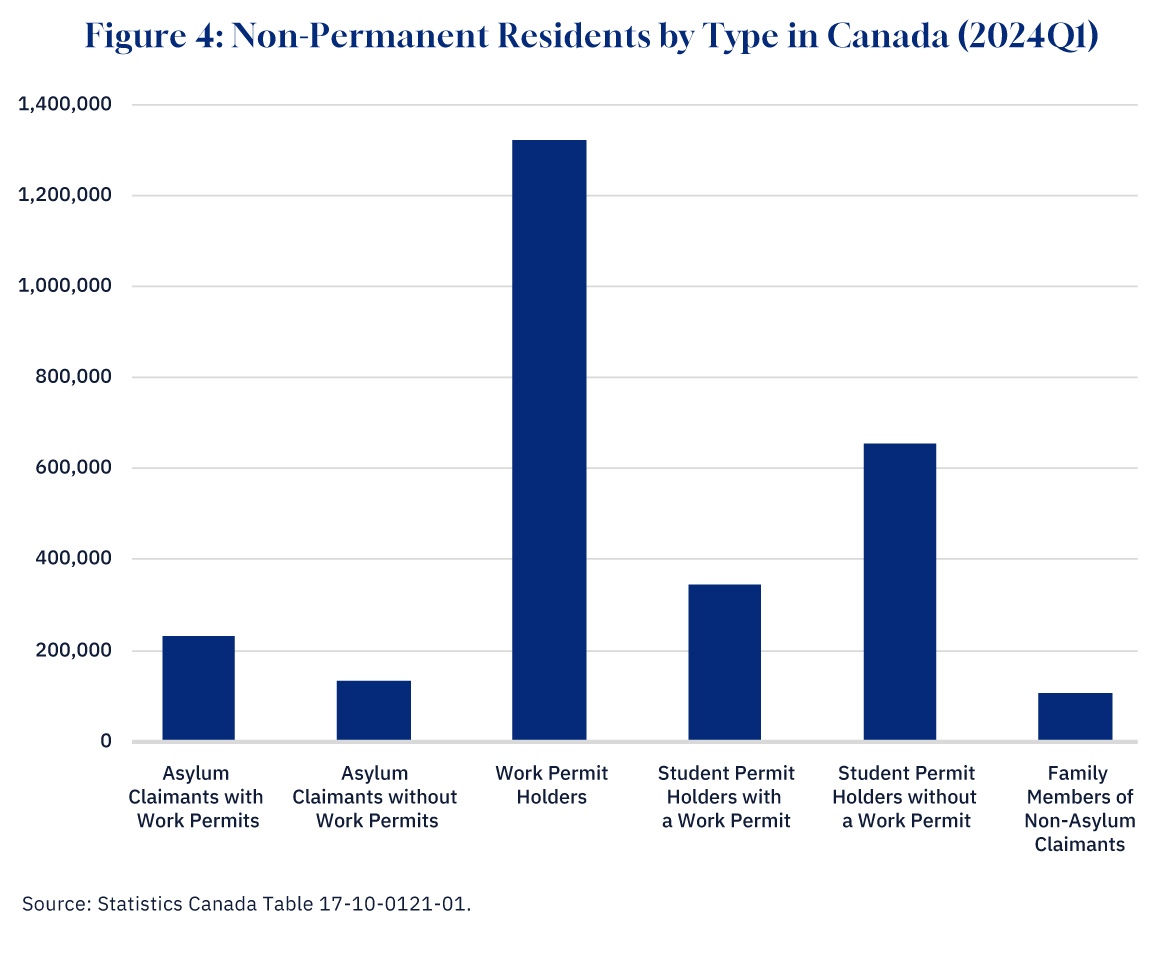

Who is included in the NPR category? Figure 4 breaks down the overall total of 2.8 million NPRs in Canada into its different components. Some are asylum claimants. This includes refugees from war-torn countries such as Ukraine, but also many people from countries like Nigeria, Mexico, and India who may be more motivated by economic circumstances. As Chart 4 shows, asylum claimants account for 360,000 of the NPRs in Canada. About two-thirds of asylum claimants have a work permit.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

A second category is temporary foreign workers—those with just a work permit. This includes not only low-skilled workers, such as people brought into the agricultural sector on a seasonal basis, but skilled workers in fields such as IT. This is by far the largest category of NPRs: 1.3 million people—about half the total.

A third category is students: Chart 4 shows that there are about a million foreign students in Canada. This is about half of the total, and of these about a third also have a work permit. Finally, there are about 100,000 family members of those NPRs who have work or study permits but who are not asylum claimants.

In total, therefore, 1.9 million (68 percent) of the 2.8 million NPRs in Canada are entitled to work. While not all NPRs with a work permit—particularly students—would actually be employed, the vast majority will be, as their residence in Canada is tied to having a job. Furthermore, it may well be that some NPRs who are not entitled to work are nonetheless doing so given that companies that hire migrants who are not entitled to work are rarely prosecuted.

Having documented the surge in Canada’s immigrant population, it is now time to look at its potential effect on productivity growth.

What drives productivity growth?

To understand the potential link between immigration and productivity, we need to have a framework for thinking about how productivity growth happens. Although there are certainly different ways to think about this question, the standard approach—reflected for example in Statistics Canada’s productivity statistics—is to ascribe growth to one of three sources: innovation; more capital goods; and/or a higher quality labour force.

The first source of productivity growth, innovation, includes new scientific discoveries (such as electricity), new ways to organize production (such as the assembly line), and new products (such as the automobile). The factors that lead to innovation and that influence the rate of adoption of new ideas, processes, and products throughout the economy are still a bit mysterious to economists, and the contribution of innovation to growth is generally measured as a residual, i.e. what can not be explained by other factors.

How might immigration affect innovation? It is certainly true that in the U.S., for example, the immigration of skilled scientists and engineers has contributed significantly to innovation. This does not seem to be as much the case for Canada or other countries, perhaps the U.S., as the world’s largest economy and strongest research universities is able to attract top talent in a way that other countries can not. It should also be borne in mind that countries like Japan and South Korea that have very little immigration have nonetheless managed to construct very innovative economies.

Immigration and the capital stock

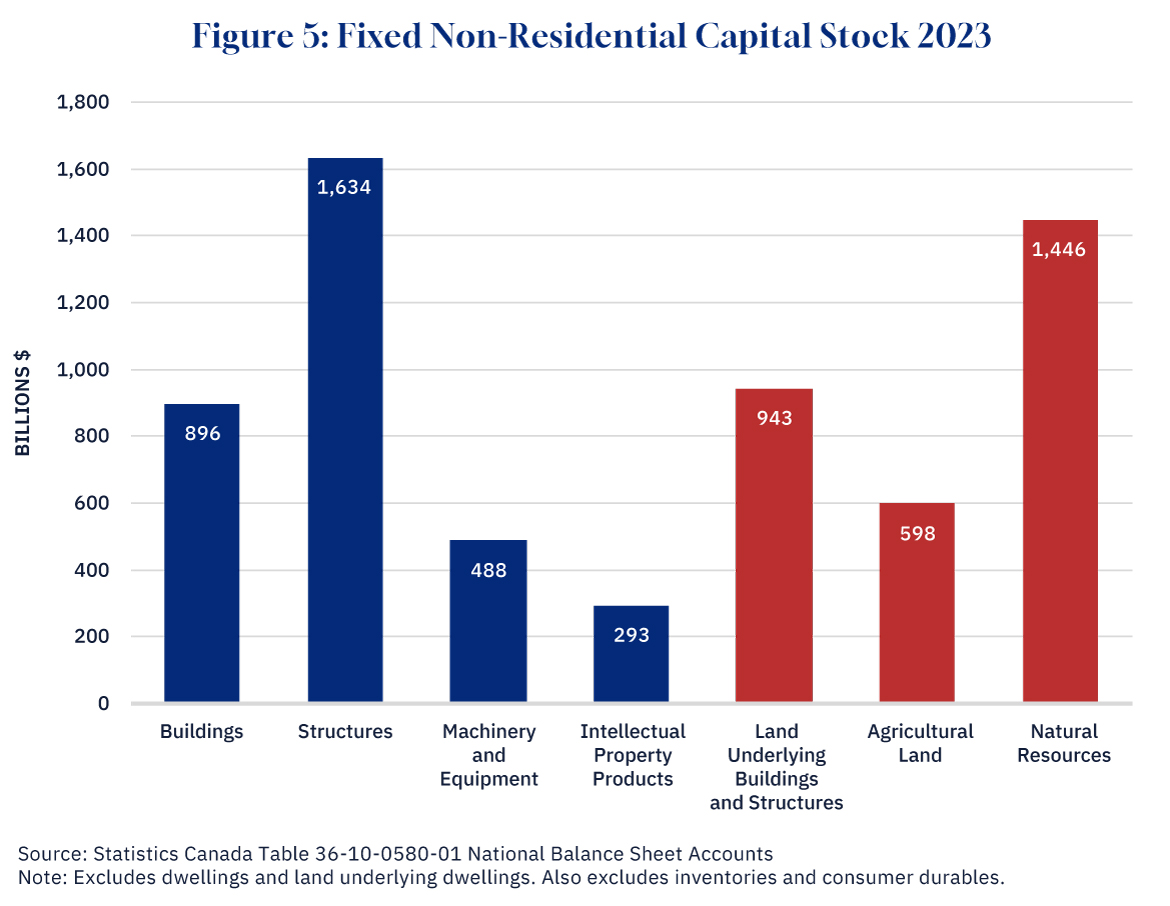

The second source of productivity growth is the capital stock, which is essentially all the things, both tangible and intangible, that are used by workers to produce goods and services. Figure 5 below shows the different components of Canada’s capital stock for 2023. On the left-hand side, in blue, are produced assets, or capital goods that have been manufactured in some way. Produced assets comprise buildings (such as factories, shopping malls, and office buildings), structures (such as highways, mines, and pipelines), machinery and equipment (such as computers and robots, but also trucks and machine tools), and intellectual property products (such as software and R&D). In total, these had a market value of $3.3 trillion dollars in 2023.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

On the right-hand side of the chart, in orange, are non-produced assets. These comprise the land upon which buildings and structures sit, agricultural land used for farming, and natural resources. The latter includes not just proven energy and mineral reserves, but also timber and even radio spectra. In total, these had a market value of $3.0 trillion in 2023.

Adding together both produced and non-produced assets gives a total of $6.3 trillion dollars, slightly more than double Canada’s GDP. This means that each Canadian worker has on average $312,000 worth of capital to help him or her produce goods and services. This average, which economists call the capital-labour ratio, is a key determinant of productivity. The more machines, factories, land, and natural resources a worker has, the more productive that worker will be.

High-income countries such as Canada or the U.S. typically have much higher capital-labour ratios than low-income countries such as India or Nigeria (the exceptions are countries like Saudi Arabia with huge oil reserves). China went from being a low-income country to an upper-middle income in large part by investing heavily in its capital stock.

What happens when there is a sudden increase in the workforce? The initial impact will be a decline in the capital-labour ratio. On average, each worker will have less capital to work with and will therefore be less productive. Output will go up—there are more workers in the economy—but output per worker will go down, putting downward pressure on wages across the economy.

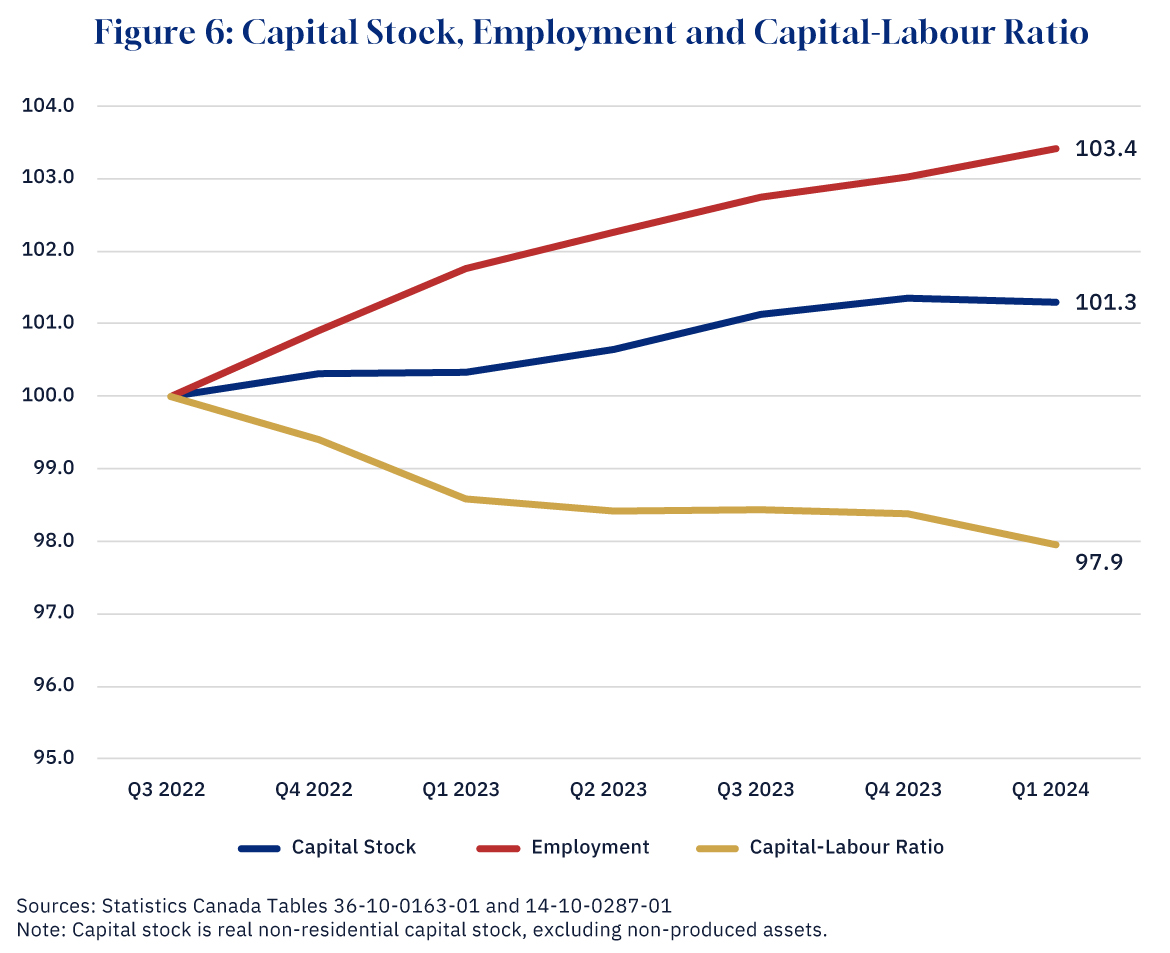

As Figure 6 shows, this is exactly what has happened. The produced capital stock has risen by more than 1 percent since the third quarter of 2002, but employment, driven by the surge in immigration, has risen by more than 3 percent, so that the capital-labour ratio has fallen by two percent, helping cause the slide in productivity that we saw in Figure 1.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Not everyone is worse off though. For the owners of capital, an influx of workers is beneficial. Workers are cheaper, and with more workers per unit of capital, they get more output. This is why business is often a strong supporter of higher levels of immigration.

In the short run, then, more immigration means lower productivity. However, what happens over time? After all, countries with bigger populations aren’t necessarily less productive. The U.S. has nearly ten times Canada’s population and has higher productivity than Canada.

The answer is that over time the capital stock, at least the produced part of it, adjusts. With a bigger economy, businesses have an incentive to invest more, and productivity will start to recover. Even the stock of non-produced assets can grow if there is more investment in mining exploration or if more land is cleared for agriculture or zoned for commercial or industrial use.

That’s the good news. The bad news is that this adjustment can take a very long time. The reason for this is that much of the capital stock is very slow to adjust. Developing more land for buildings or factories is a notoriously long process in Canada, and the time it takes to get permission for a major resource project is even longer. Even without these external constraints, it takes time to plan, get internal approvals, arrange financing, and actually complete construction. According to the head of the Mining Association of Canada, a new mine can take up to 15 years to become operational.

Thus, at least in the near term, we would expect an increase in immigration to reduce productivity, as the existing stock of capital, both produced and non-produced, now has to support a greater number of workers. Just as in the housing market, the supply of physical assets cannot adjust quickly to a surge in population.

Immigration and labour quality

The third driver of productivity growth is the quality of the labour force, or how much human capital—skills, education, experience—that a worker possesses.

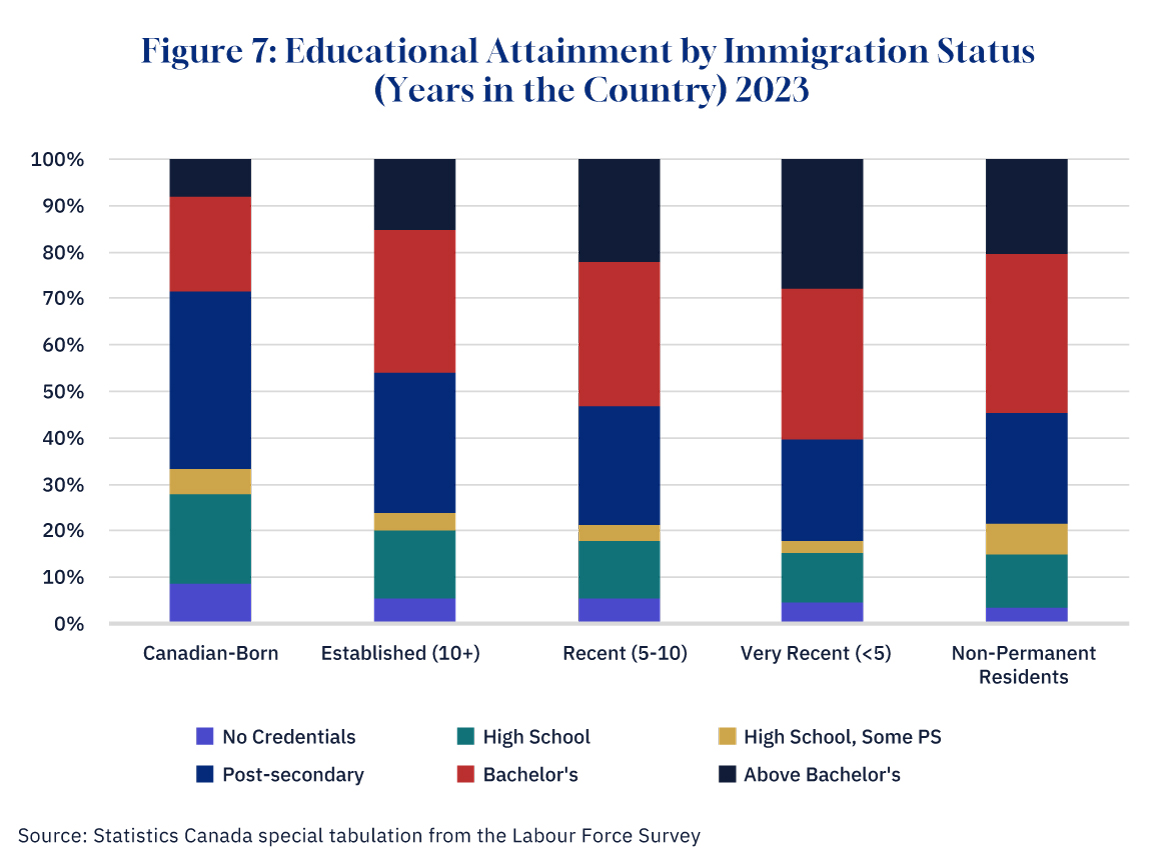

If immigrant workers had the same characteristics as Canadian-born workers, we would expect immigration to have no impact on labour quality. However, immigrants do not have the same characteristics as Canadian-born workers. On the one hand, the countries that Canada draws the bulk of its immigrants from (India and China) have much lower levels of human capital than Canada. On the other hand, those who choose to emigrate are often better educated, and our immigration system is designed, in part, to select for the “best and the brightest”—immigrants with more human capital.

In practice, what we see is that immigrants do have fairly high levels of educational attainment. In Figure 7 below we can see that 60 percent of very recent immigrants, and 55 percent of non-permanent residents, have a bachelor’s degree or above. In comparison, less than 30 percent of the Canadian-born population has a bachelor’s degree or above. (Of course, it may well be that the Labour Force Survey does not capture many lower-skilled immigrants who may not be as willing or indeed able to participate in surveys.)

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

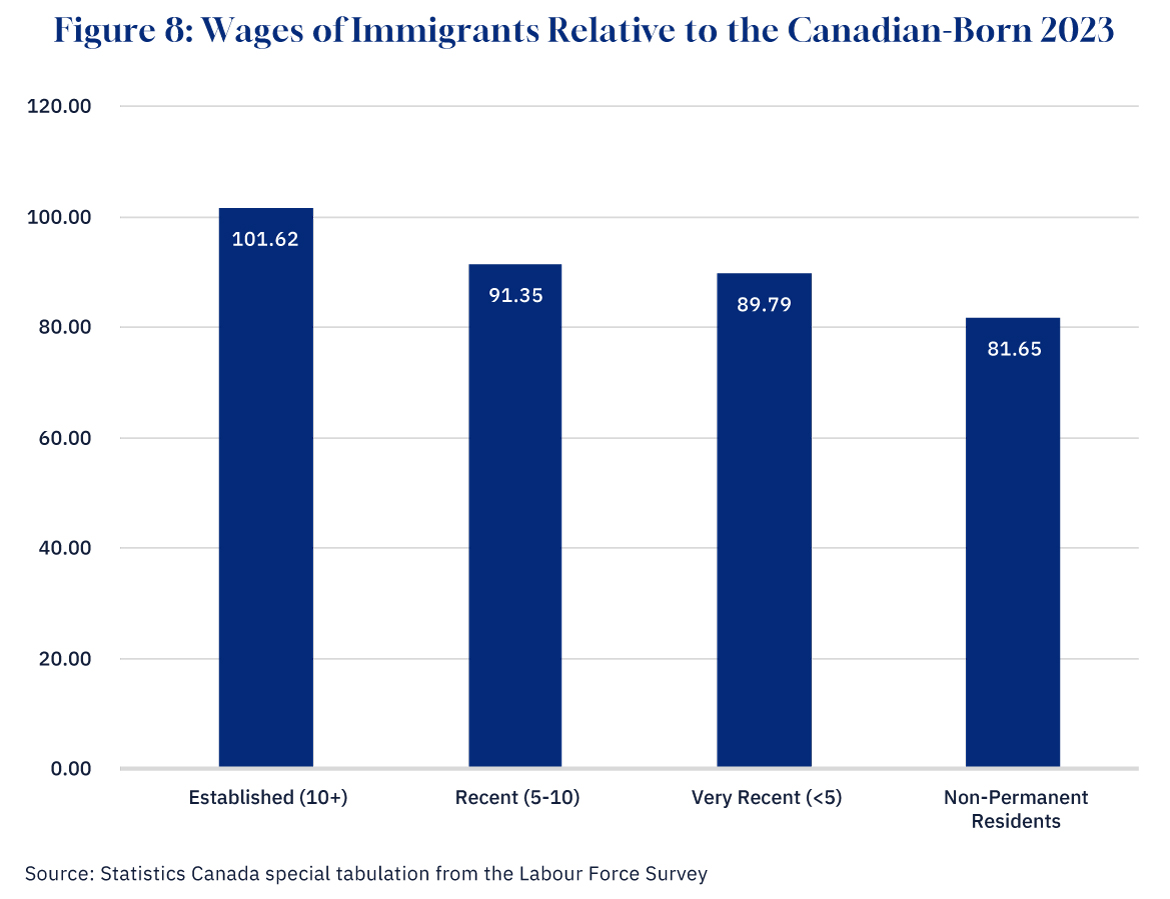

However, this superiority in educational credentials does not necessarily translate into higher earnings. In Figure 8 below, we show the wages of immigrants relative to Canadian-born workers. Established immigrants—those who have been permanent residents of Canada more than ten years—have earnings slightly above that of the Canadian-born. However, recent immigrants—permanent residents between five to 10 years—and very recent immigrants—permanent residents for less than five years, have earnings that are around 90 percent of Canadian-born workers. Non-permanent residents have even lower relative earnings—slightly above 80 percent of Canadian-born workers.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

This suggests that recent immigrants’ credentials are less valued, or that they have less relevant work experience or skills. Lack of familiarity with Canada’s official languages and culture may also play a role. Occupational licensing barriers are also likely to impede educated immigrants from entering many professions given that it is not always easy for professionals to be licenced if they come from another province of Canada, let alone another country.

Could outright discrimination against visible minorities play a role, with employers offering wages to recent immigrants that are lower than their level of productivity? The fact that established immigrants have caught up with their Canadian counterparts would seem to suggest not. Time in Canada, rather than ethnic origin, seems to be what is driving lower wages for immigrants. (Note that even among established immigrants, only 23 percent were born in Europe and the U.S.)

However, while the wage gap between immigrants and the Canadian-born does dissipate, it takes a significant amount of time: as Chart 7 shows, those immigrants who have been in Canada for five to 10 years still earn only 91 percent of the Canadian-born. This suggests that a surge in immigration such as the one that we have just experienced is likely to reduce labour quality for a long period of time until the new arrivals catch up.

Key takeaways: do the negative impacts on productivity mean that immigration is negative for the Canadian economy?

It does seem likely then that the surge in immigration over the last few years, particularly amongst NPRs, has contributed to the recent decline in Canada’s productivity. Because the capital stock moves slowly, faster population growth reduces the available stock of machinery, buildings, and natural resources per worker, making them less productive. And because new immigrants and NPRs are less productive than immigrants who have been in the country for a long period of time, a surge in immigration lowers the average quality of the workforce. The other key driver of growth, innovation, is unlikely to respond significantly to immigration, given that ideas tend to flow easily over national borders.

None of this means that no one in the economy benefits from immigration. Owners of capital certainly benefit when labour is cheaper and more abundant. However, the principal beneficiaries of immigration are immigrants themselves. Given the huge wage disparities between Canada and the developing countries from which the vast majority of immigrants come from, the potential economic gain to immigrants is very large. The costs of relocating and adapting to a new country are small in comparison.

Furthermore, there are things governments can do to improve the economy’s adjustment to the higher immigration. Policies to improve the investment climate would help increase the capital stock, and better credential recognition would reduce the wage gap for new immigrants.

However, policy action on these fronts can only go so far. Ultimately, it is always going to take some time for the capital stock to catch up with a bigger workforce, and new immigrants are likely to be less productive for a significant period (unless Canada is willing to become much more selective in its immigration policy, cutting back on family class immigrants, and making selection criteria much more stringent). This means that if immigration remains at its current level, it is likely to remain a drag on productivity and therefore our standard of living for some time to come. Whether that proves politically sustainable remains to be seen.