A majority of Canadians think that Canada is broken after years of stagnant incomes, affordability challenges, rising crime, government failures on basic functions like healthcare and immigration, and a deepening cultural malaise. But decline is a choice, and better public policies are needed to overcome Canada’s many challenges. Kickstart Canada brings together leading voices in academia, think tanks, and business to lay out an optimistic vision for Canada’s future, providing the policy ideas that governments need to ensure a bright future for all Canadians.

The federal government has heard the message from economists, the Bank of Canada, and Statistics Canada clearly: Canada’s productivity growth is dismal. Without a policy change, the OECD forecasts that our productivity growth will rank last among its 38 member countries.

While many think productivity is an arcane measurement of interest only to economists, that understanding is fundamentally incorrect. Productivity is how efficiently we use our resources to produce something of value. Productivity growth makes Canada richer, allowing us to access better healthcare, education, living standards, and even environmental outcomes.

Coming out of this week’s cabinet retreat, Treasury Board president Anita Anand announced a new federal working group to “investigate Canada’s low productivity levels.” Here are some policy areas and actions that the working group should pursue to reverse our productivity decline.

Childcare policies

Accessible and affordable childcare is crucial for economic growth, enabling more women to join the workforce. In 2021, the federal government introduced its $10-a-day childcare program, intending to open 250,000 new spaces by 2026. While the concept is sound, the government’s implementation has been flawed. The program is experiencing delays, is administratively intensive, and explicitly favours public and not-for-profit providers, sidelining the private sector.

Statistics Canada data shows that across Canada, the proportion of children five years and younger in childcare dropped by almost 4 percent between 2019 and 2023. Over the same period, the proportion of families having difficulty seeking childcare increased from 36 to 46 percent.

Excluding private day-care providers, which are mostly women-owned, combined with administrative burden and competition from subsidized rates, works against the primary goal of increasing licensed spaces. Inadequate funding has even forced some providers to drop out and raise rates to remain viable. The result? Female participation in the labour force has stagnated at 61.3 percent in May 2024, virtually unchanged from 61.4 percent in May 2015.

Government debt and private investment

Between 2015 and 2024, federal government debt ballooned from $660 billion to $1.37 trillion. During the same period, the value of machinery and equipment in Canada decreased by 5 percent in real terms. While many factors influence business investment decisions, this correlation suggests that increased government borrowing may be crowding out private-sector investment, a well-documented phenomenon in economic literature.

Research also suggests that the appropriate size of government ranges around 26 to 35 percent of GDP, beyond which additional benefits are minimal. However, Canada’s cumulative government expenditures have consistently exceeded this range, standing at 40 percent in 2022 and remaining above 35 percent annually since 2007.

Excessive government spending hinders economic growth by crowding out private investment and requiring higher taxes to support increased spending. It leads to a heavier regulatory burden, which can stifle business activity. Government programs also adjust more slowly to changing economic conditions, reducing economic flexibility. Moreover, larger government expenditures encourage rent-seeking behaviour by businesses, diverting resources from otherwise productive activities. Collectively, these effects reduce productivity and economic growth.

Labour shortages

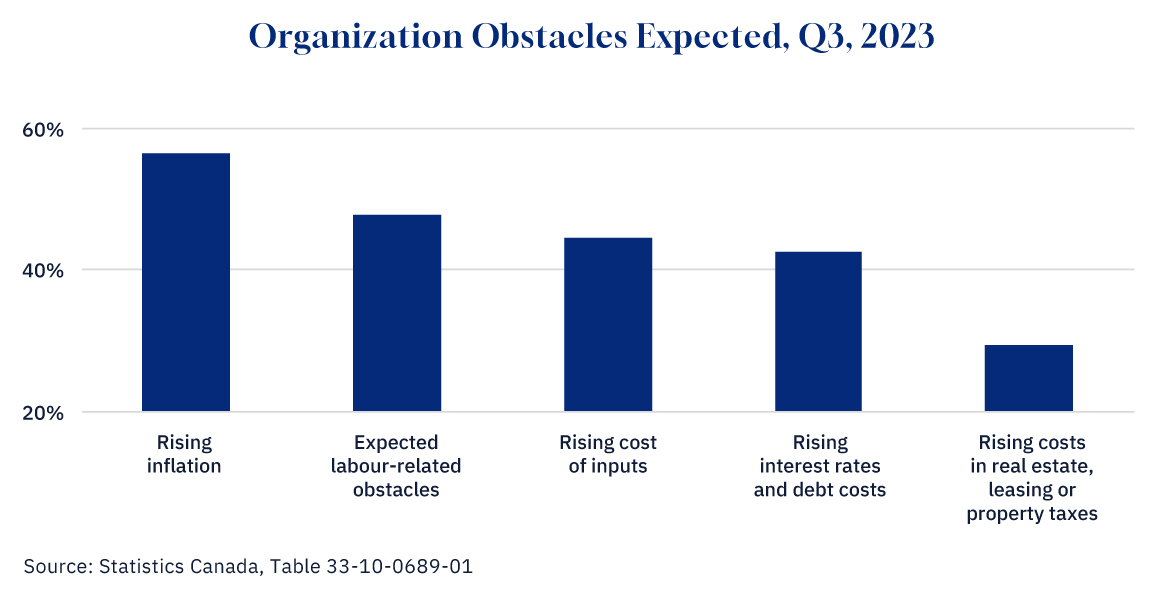

A Statistics Canada survey for Q3 2023 shows that labour-related obstacles are the second greatest concern identified for businesses, surpassing even rising interest rates and real estate/leasing costs.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

In 2022, labour shortages cost small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs) over $38 billion in lost sales. Meanwhile, between 2015 and 2024, federal public-sector employment has grown 43 percent, nearly three times faster than private-sector employment growth.

If the federal public sector had kept the same growth rate as the nation’s population, there could potentially be up to 72,000 more workers available for employment in the private sector. Assuming two out of three workers were employed by SMEs, and using an average of $450,000 revenue per employee, SMEs could have generated over $21 billion in additional annual revenue.

Tax policies

In 2016, the federal government raised the highest federal marginal tax rate by 4 percent. Combined with provincial rate increases, seven out of 10 provinces now take over 50 percent of marginal earnings in taxes from high-income earners. Additionally, the capital gains tax rate increased from 50 to 67 percent on gains over $250,000.

Canada now has the fifth-highest combined marginal tax rates among 38 OECD nations. Compared to the United States, our largest competitor for skilled workers, all provinces except Alberta and Saskatchewan have higher marginal tax rates than all 50 U.S. states.

These tax hikes have consequences. Research shows that higher corporate and personal taxes reduce the amount of innovation and where it occurs. Jason Smith, CEO of Klue Labs, captured the sentiment well when he said, “Canadians teeter on edge on starting their companies in Canada or going to the U.S. Every incremental tax makes us think twice about starting companies in Canada.”

Policy recommendations

- Scrap the current childcare plan and implement a demand-driven system. Give money directly to families and let them choose the care that works best. This will spur the creation of new spaces across both for-profit and non-profit providers. Childcare will become more affordable and will, in turn, also improve the participation rate of women in the workforce.

- Reduce the government’s economic footprint. Aim to reduce total government spending to no more than 35 percent of GDP. Start by reducing the size of the federal public sector to its 2015 proportional size relative to population. This will help address labour shortages and reduce government expenditures, contributing to a smaller, more efficient government.

- Eliminate or significantly reduce direct business subsidies. Instead, encourage growth by streamlining regulations and removing entry barriers, fostering a more dynamic and competitive business environment.

- Rescind the recent tax hikes on capital gains and lower marginal tax rates on high earners to stimulate domestic innovation and entrepreneurship. These changes will help Canada compete with the U.S. in attracting and retaining top talent and innovative companies. The ability to implement these tax reductions depends on reducing expenditures through public sector downsizing and other cost-cutting measures.

The path to improving Canada’s productivity is clear and achievable. The necessary changes are neither complicated nor controversial. They are good government management practices ensuring that the private sector has access to capital and labour, as well as incentives to innovate and grow.

Policies relying on government intervention to replace the free market seldom produce improved growth and productivity. By implementing these measures and allowing the private sector to lead, a future Canadian government can create an environment where productivity and prosperity can flourish for all Canadians.