The federal election scheduled for next year presents Pierre Poilievre and the Conservative Party with two distinct but interconnected opportunities. The first is a political opportunity to redefine the centre in Canadian politics. The second, a policy opportunity to implement transformational and lasting change in Ottawa—the change required to actually fix a “broken” Canada.

The list of Canadian conservatives who have been able to successfully seize such opportunities is short. It does include one name with particular relevance to the present time: former Ontario Premier Mike Harris. Harris created the original “common sense” brand, and it helped him achieve back-to-back landslide majorities and enabled a series of fundamental alterations to the policy status quo in Ontario—alterations that proved both consequential and long-lasting.

In this two-part essay, Alister Campbell (“message guy” in the Harris “Common Sense Revolution” campaign of 1995 and editor of The Harris Legacy) outlines key lessons the Poilievre team must learn from the Harris story. Here’s part one.

“We were raised on the faith

The center’s holding

And can’t be broken

And now that it’s started

It might not stop”

Maybe only a few Hub readers listen to Dinosaur Jr. (a grunge-era band led by guitar god J. Mascis), but I suspect many more share their worry about the degree of polarization in the political discourse of the Western world these days.

To some extent it can be argued that this uncomfortably high degree of recent tensions is actually normal. It may be that the benign post-Second World War-era of Western hegemony and the broad-based consensus on general political themes (including collective security, liberalized trade, progressive taxation to fund government programs for the less fortunate, etc.) is actually the outlier and bitter conflict is the norm. Certainly, the authoritarians of the world (Putin, Xi, Khameini, Kim, etc.) are united in their view that a world of successful democratic capitalism is not for them and they would prefer a return to Cold War conflict (or worse).

But for the multiple generations of Canadians (and subscribers to The Hub) who have lived, worked, and raised their families in this prosperous G7 country—never having had to serve in a military at war—it is hard to argue with the benefits of a more consensus-based polity. In many ways, a country with a centrist majority carefully skirting the extremes at both ends of the spectrum has proven to be a pretty good deal.

For conservatives in Canada however, this deal has always required an uncomfortable amount of compromise. Over decades. Political historians would probably differ on details, but sometime around the time(s) of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, the federal Liberal Party evolved into “Canada’s natural governing party.” Carefully fencing off their more socialistically-inclined activists in a separate New Democratic Party (who fenced off their own Communists), they have been able to position themselves at the centre of our politics for the many decades since. And using the NDP as a lever, they have also been able to consistently force Canada to embrace regular and climbing increments of increased government spending and state intervention.

When the Conservatives resist, they are painted (all too often successfully) as “extremists” and “outside the mainstream.” And when so painted, they are then regularly defeated by either Liberal majorities or Liberal minorities collaborating with the NDP as joint custodians of a centre-left status quo.

Two separate streams of conservative activism rebelled against this seemingly permanent role as Canada’s “natural official Opposition party” in the course of the 1980s. One stream came from the party and expressed itself in the triumphant, landslide 1984 election victory of Brian Mulroney. While still embracing the traditions of “progressive conservatism,” Mulroney refused to accept the electoral status quo, and by breaching the Liberal fortress in Quebec, delivered two consecutive majorities to the party.

The second stream (ironically) chose this same period to declare its unwillingness to be bound by the old deal at all. Preston Manning led a rising tide of populist discomfort with the centrist status quo and accomplished something almost as extraordinary as Mulroney’s winning 50-plus seats in Quebec: the founding of an entirely new Reform Party which, within three elections, was itself Canada’s new official Opposition. The irony is that the success of the second conservative movement guaranteed the near extermination of the first. And this divided Right made for easy pickings and guaranteed the Liberals under Chretien/Martin four consecutive terms in power.

It took an agonizingly slow process—including the formation of the Canadian Alliance (CA) and the eventual merger of the CA with the remaining rump of PCs—to recreate a single, new, and integrated conservative party in Canada. Under the leadership of Stephen Harper, the (re)united Conservatives, were almost instantly rewarded with government, in the face of a particularly divided Left (Liberals/NDP/Bloc and Green).

Harper’s time in office also revealed just how hard it is to shift the centre in this country. Even small nudges to the status quo brought howls of anguish from its beneficiaries, amplified by a mainstream media inclined to believe that the status quo was in fact holy writ and it was blasphemy to amend.

And then Justin Trudeau.

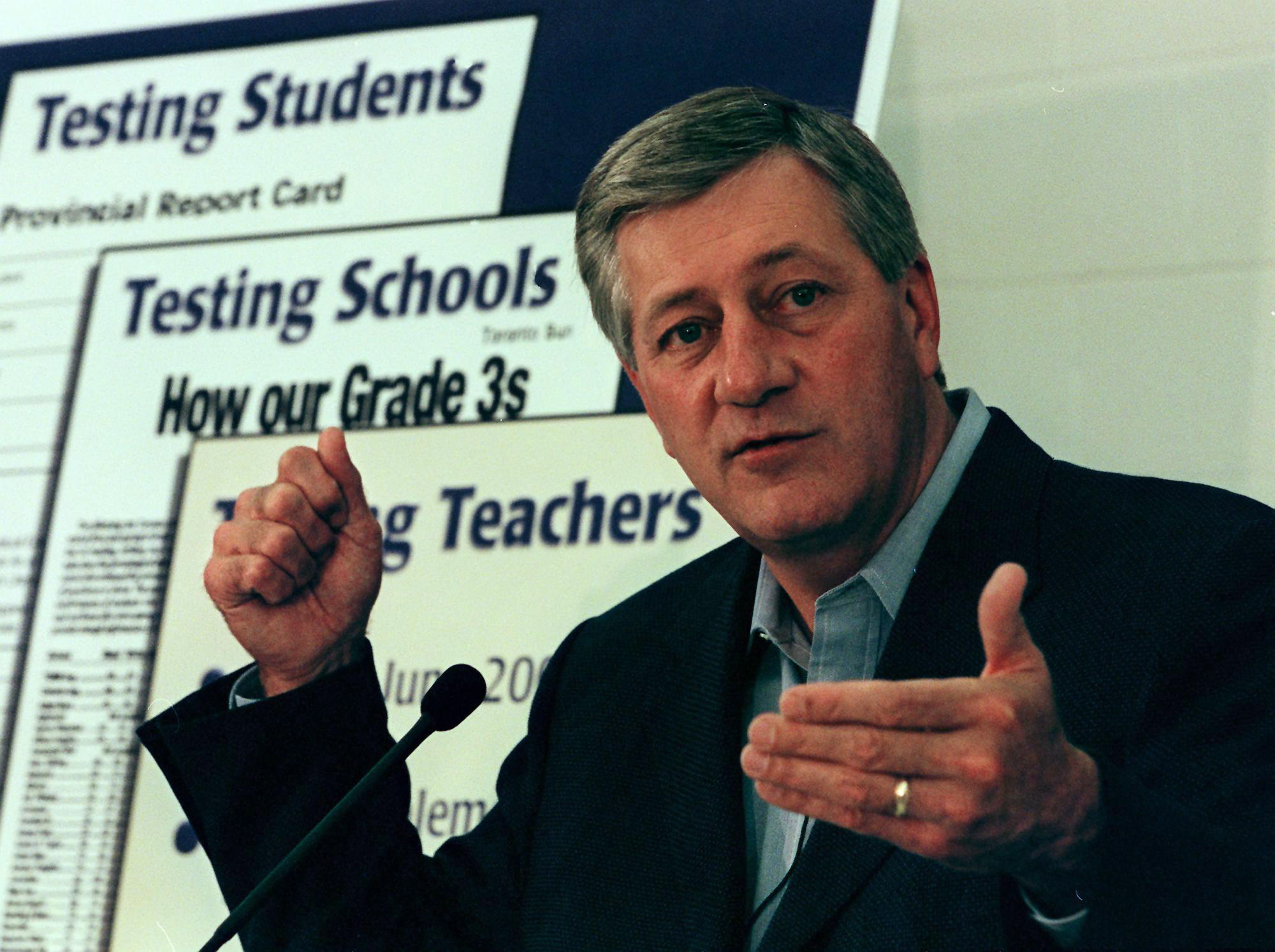

Ontario Premier Mike Harris gestures at a press conference held at Sheridan College in Oakville Ont., Friday, May 28, 1999. Rene Johnston/CP Photo.

A long way to get to my point regarding polarization. If the second half of the 20th century was a benign period with a strong bias towards the centre, it was in large part a response to the appalling human consequences of the radical polarization seen in the first half of that century. The democracies did win, but only at great cost, when the extremes of the Left (Stalinist Communism) contested for dominance with the extremes of the Right (Hitler’s National Socialism).

Some see politics as a continuum, and those who do, describe a barbell with a slim connecting bar holding together two heavy bulbous ends. In this metaphor, the centre is the slim connecting bar. If the ends get too large, or if the connecting bar gets too thin, then it will break—“the centre will not hold.” Other political scientists argue that this continuum is actually circular with the extremes of the Left and Right meeting at the back/bottom of the circle. One of The Hub’s founding editors has recently described the unnerving number of policy areas where Donald Trump’s vice-presidential candidate JD Vance has espoused views that match closely with the most progressive extremists increasingly driving today’s Democratic Party. That would be a vivid illustration of the potentially circular nature of policy and politics at the extremes.

But I do not believe the logical or sensible Conservative response to this current polarization should be to simply revert to the traditional, centrist, status quo deal. For several important reasons.

First, because that traditional deal has meant increasingly bad policy for Canada. Weak economic growth, low productivity, an abandonment of key strategic, competitive advantages (effective exploitation of our natural resources, control over the quantity/quality of immigrants, etc.) a complete/wanton disregard of our obligations as a democratic nation to ensure adequate defence capacity for our own sovereignty in the North or our NATO allies, the continued granting of bail to repeat, violent offenders…the list goes on. To describe the status quo as broken appears to me to be almost polite.

Second, the current federal Liberal Party is no longer capable of honouring their part of that traditional bargain. Central to the old “deal” was a commitment from both parties of the centre that they would not tolerate the extremes within their fold. The NDP/Liberals worked to ensure that their tent did not encompass avowed Communists. And the Conservatives committed to ensure that no white, ethno-nationalist strain of lunatics were allowed inside their tent. Today’s multi-racial and open Conservative Party shows no tolerance for the foul strains of this nationalist or racism. However, the liberal Left parties no longer seems capable of honouring their part of this bargain. It’s no longer traditional “Communism” which is infecting their party. In some ways it is something even worse.

Today’s progressive Left is guided by a comprehensive worldview that seems to equate evil with a so-called colonialist and patriarchal hierarchy that its exponents are on a mission to deconstruct with messianic fervour. This extremist worldview is deathly serious. And insane, as it views all issues through a single, race-based lens (substituting out Marx’s class-based filter for something equally myopic).

Its logical outcome is fundamentally in opposition to all the centre’s traditional, Western, liberal democratic values. It appears that, in their hearts, today’s Liberal Party believes these people are right. Many of its members certainly share the ideology of the climate extremists, who are demanding no less than the unilateral abandonment of the blessings we have all received from the output of a well-regulated capitalist economy. These two extremist cadres now control both Canada’s Liberals and NDP. The net result is a governing coalition that has nothing but contempt for its own country—our history, our citizens, and, in fact, anyone who does not share this reductionist and destructive worldview. Today’s Liberal Party is on a mission to transform us into something only tenured professors in love with acronyms like DEI and ESG could dream up.

The good news is that the people of Canada are not ready to go there. The upswelling in support for the federal Conservatives in recent months—including among newer Canadians—has several explanations.

First is the utterly normal and healthy belief that, after so many terms in power for a single party, it is time for a change. Second, there is clearly some voter exhaustion with the sonic torture that listening to our unctuous and condescending incumbent PM entails. Far more significant, the strong lead of the Conservatives in all recent polls is directly correlated with a near-universal appetite for a restoration of common sense in government. A government led by people who do not appear to hold their fellow citizens in such low regard.

Mike Harris and Preston Manning take part in a panel discussion during the Canada Strong and Free conference in Ottawa on Friday, May 6, 2022. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

In this time, when the traditional natural governing party has lost its way, unable or unwilling to purge its extremist elements and ideologies, there is now room for Canada’s Conservative Party to carve out a new centre. Common sense elements of this will logically include:

- A restoration of fiscal balance;

- a new agenda to restore Canada’s capacity for higher productivity and economic growth (including marginal income tax rates with an upper bound below 50 percent);

- a strategic approach to immigration;

- a renewed commitment to an effective and efficient federal civil service, executing its core functions with professionalism while leaving the provinces to do their jobs with less interference;

- a justice system that successfully puts criminals before the courts, keeps repeat and violent offenders incarcerated before trial and, upon conviction, in jail for appropriately lengthy sentences;

- a recognition that the single best thing Canada can do to help the planet reach net-zero is to successfully export our natural gas to China and India so they can stop burning thermal coal;

- the realization that Canada can have no credible foreign policy without spending two percent of GDP on our armed forces within the first term of a new government;

- a commitment to reconciliation with First Nations based on private property rights and by ensuring they share fully in our natural resource (and other) riches;

- enabling innovation in service delivery to fix our no-longer-best-in-class health-care system;

- And a renewed commitment to balance in regard to where the state and the family intersect on issues of public health.

This whole list will madden the Left. But to the centrist majority in Canada, these items are just common sense. And that is exactly why this opportunity to shift the centre is generational.

Ontario’s Mike Harris first created the “Common Sense” brand—which Poilievre has now firmly adopted as his own—in the 1990s. Ontario had fallen on very tough times and there was a huge majority of the electorate ready to respond to proposals for major change. Harris delivered that change in style. And in so doing, shifted the political centre in Ontario.

I believe there are three points in particular about Harris’ Common Sense Revolution (CSR) which could be particularly instructive for the Conservative Party leader and those crafting his campaign strategy.

First, the reason the CSR is remembered today, when so many other platforms since are long forgotten, is not because it was a central element of an unexpectedly successful Canadian political campaign (although it was that). Rather, it is because Harris then diligently went about actually implementing the rich and well-thought-out policy content of that platform. And he won a second majority, with an increased plurality, primarily because he had done when he said he would do. It is a mistake to think that the CSR was just good marketing. It was not just a meme. True common sense requires a robust policy framework with a comprehensive array of actual planned actions.

The second point is that Mike Harris’ opponents tried to tar him as a right-wing extremist, using the traditional progressive Left strategy that had worked so often before. They failed because Harris’s common sense agenda actually spoke to the broad centrist majority of Ontario. The policies he articulated and implemented were seen by the majority of Ontarians as perfectly reasonable, sensible, and long overdue.

Finally, a critical component of the Harris political strategy was to demonstrate a true commitment to change by forcefully articulating policies guaranteed to enrage the mainstream media, and then reaffirming commitment to these policies in the face of the ensuing controversy. But the choice of policies was deliberate and directly aligned with his thinking around re-defining the centre. Policies such as mandatory work for welfare (1995) or mandatory teacher-testing (1999) were seen by the Left as extreme. But the Harris team knew these so-called wedge issues were in fact supported by the vast majority of target “persuadable” voters. Issue selection is key.

It is always tempting for Conservatives to poke the Left for amusement. Or deliberately showcase policies to reinforce support from the core. Poilievre and his team must eschew this temptation. Common sense victories are won by speaking to the accessible majority. And the policies selected for focus should always be those that help broaden out a centre-right coalition.

These practical political stratagems were central to Harris’ success in redefining the centre and creating a powerful and lasting common sense brand. But, Harris is a rare exemplar of a Canadian conservative able to achieve both sustained political success and transformational policy consequences. In the second part of this essay (in The Hub next Saturday), I will discuss some lessons from Harris’ time in government and what they can teach Poilievre about how to be a transformational prime minister.