Last year, I thought it would be a romantic Hawaiian honeymoon destination to visit America’s most famous battleship. The beautiful 80-year-old, 45,000-ton USS Missouri played a key role in the Second World War’s invasion of Iwo Jima, the Korean War—and, incredibly, even the first Gulf War. Most importantly, however, 79 years ago today, a tiny spot on its 1.2 acres of teak deck was the site of Japan signing its document of surrender, which formally ended the Second World War.

It was a defining moment, marking the conclusion of a six year long conflict that killed 75 million people and reshaped the modern world. It was also a moment that marked one of the most monumental Canadian screw-ups in history.

As the Globe and Mail described it nearly 80 years ago, it “will rank high among the historic bobbles of our time.”

A floating spectacle

According to my American tour guide, it was the USS Missouri, eight decades ago, that played the leading role in a triumphant display of American dominance, featuring a fighter aircraft armada and 250 warships anchored in Tokyo Bay. The German surrender four months earlier was a solemn affair. The surrender in Japan would be a spectacle.

The exhausted and recently atom-bombed Japanese delegation was brought onboard and immediately blinded by the flashbulbs of 300 invited journalists. Only a few days earlier the hundreds of soldiers straining their necks to catch a glimpse of their defeated foes, had been readying themselves for “Operation Downfall”—the invasion of Japan. But that was before Emperor Hirohito defied his generals and finally submitted to the Allies.

The humiliated Japanese were led to a table and chairs and greeted by the top brass from all the Allied nations, led by U.S. General Douglas MacArthur who had orchestrated the affair. Every Allied power (the U.S., the U.K., France, the Netherlands, China, the Soviet Union, Australia, and New Zealand) was represented by a general, marshal, or admiral. Every country except for Canada.

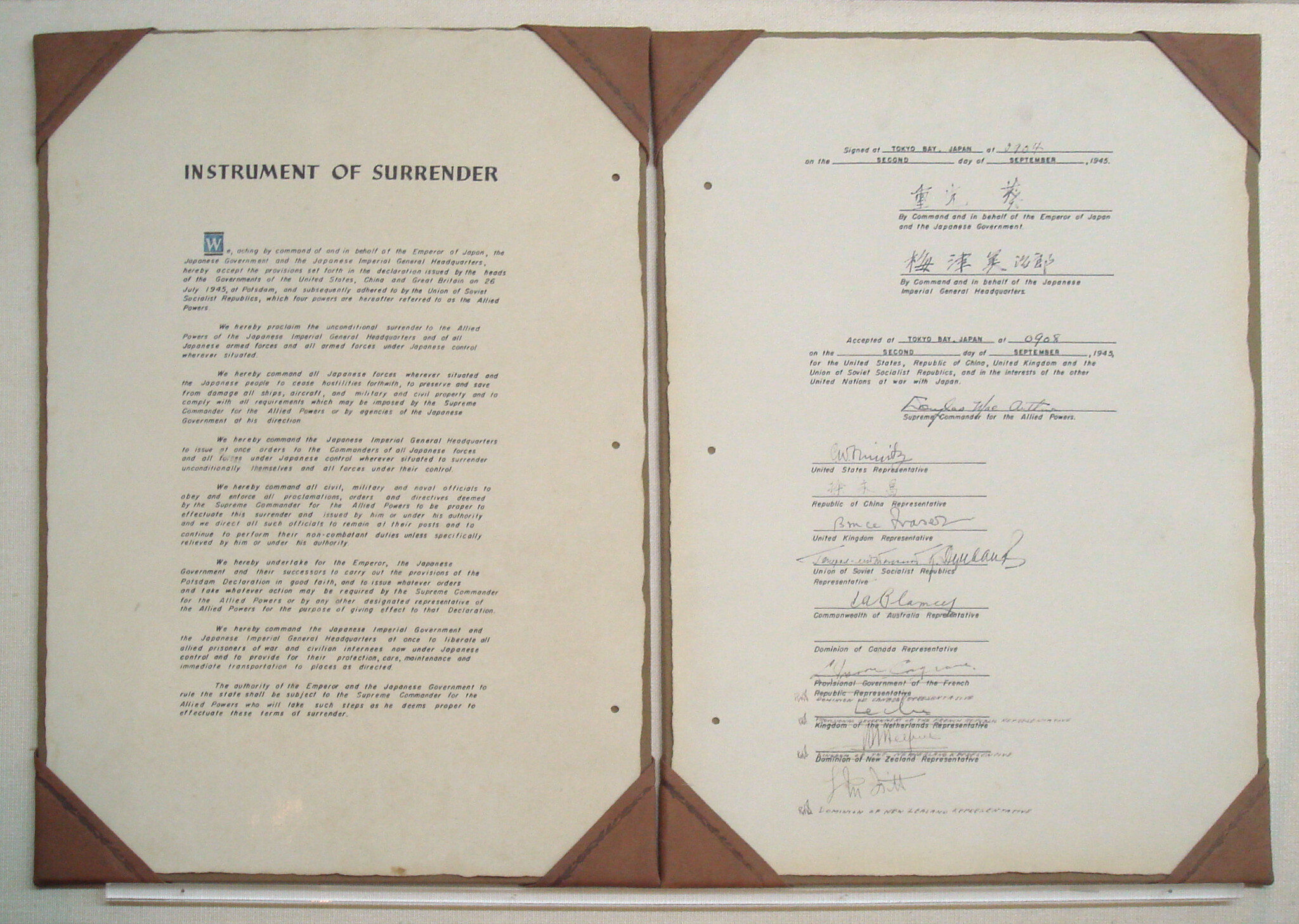

Signing the “Japanese Instrument of Surrender” for Canada, arguably one of the most important documents in history, was one Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave.

As our American guide explained to me, my new wife, and our fellow tourists, Canada did not have a high-ranking officer available in the region. The man who should have been representing us was Major-General Bert Hoffmeister, a distinguished veteran in the Italian campaign who had helped lead the epic capture of Ortona.

But Bert was stuck in Vancouver.

So, Canada had to settle for Cosgrave, our Australian military attaché—a man who only had one functioning eye and who one of the American generals on board described as, “An elderly masher of the gigolo type.”

This was a significant moment for our country. In their heroic 1941 defence of Hong Kong, Canadians were the first to declare war on Japan and took part in one of the first-ever battles in the Pacific. We lost nearly 300 men in the process. More than 260 Canadian prisoners of war later died in Japanese custody from starvation, sickness, forced labour, and horrific abuse. Some emaciated Allied soldiers were even at the signing ceremony, their protruding rib cages in full view of their former captors. Canada’s signature on that surrender document would be some measure of revenge.

Allied delegates gather on the deck of the USS Missouri to receive the Empire of Japan’s surrender on September 2, 1945. Photo credit: U.S. government.

A famous flub

Sadly, it was not to be. Cosgrave would make his mark on history—but in all the wrong ways. When it was Canada’s turn to sign the Japanese copy of the surrender document, instead of putting his signature on the designated line above “The Dominion of Canada,” Cosgrave accidentally wrote it on the line below, where France was meant to sign. Observers questioned if Cosgrave had been distracted. Others blamed his partial blindness. Still others speculated if he was drunk.

“There was a sense of this big ceremony we had set up. Everything is supposed to go off right. And then, ‘oops’,” Michael Pass, a historian and expert in Canadian-Japanese relations told me in an interview.

“[H]istory cruelly remembers him only as the man whose brief walk on the world stage was marred by a misplaced signature,” wrote veteran reporter Geoff Ellwand years later.

With his blunder, Colonel Cosgrave set off a chain reaction of confusion. The French and Dutch were then forced to sign on the wrong line, relegating the Kiwis to the empty space at the bottom of the page.

When the Japanese eventually came to retrieve the document that marked the defeat of their empire, the ship’s captain said they “started to question something on it.” The perturbed party wondered whether the document was legal. They seemingly refused to accept it, botched by Canadian hands. As minutes ticked by, and the end of the war was delayed, the USS Missouri ran the risk of becoming the site of an international incident.

“The Canadian messed it up,” announced our American tour guide. I stared down at the deck avoiding the gaze of fellow tourists we had proudly told we were from Toronto. I spent the time doing the mental math, concluding that every hour, visitors to the Missouri were being told Canada screwed up signing one of history’s most important documents. We were an international laughingstock. But were we really?

Canadian representative Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on Canada’s behalf aboard the USS Missouri. Photo credit: Keystone/Hulton archive/Getty Images

Canadian Colonel Cosgrave

It was only by ignoring American tour guides, going back to my honeymoon hotel room, and digging deeper into Canadian history that I learned that rather than laughing at Clumsy Cosgrave, we should be thanking him.

Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, born in Toronto in 1890, truly served his country not during the Second World War but during the First World War. That blind eye of his? It was likely the result of him surviving the first-ever gas attack in Ypres, while still managing to help fend off a German attack. He would also fight at Vimy Ridge, the Somme, and Passchendaele. Cosgrave emerged on the other side of the Great War with a Distinguished Service Order (twice) for “conspicuous gallantry in action”. France awarded him the Croix de Guerre, for his feats of bravery.

Deeply damaged by the “soul-deadening trench warfare,” he then took to writing about his experience. He may have been inspired to write by his friend Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, the famous Canadian poet soldier, who shared a dugout with him on the Western Front. The story goes that McRae wrote “In Flanders Fields” on a scrap of paper on Cosgrave’s back during a break in the shooting.

Cosgrave would go on to work as a Canadian trade commissioner in China, before settling in Australia as our military attaché. Being stationed in the region, he witnessed firsthand the devastation the war’s final months had had on Japanese civilians. He felt deeply sorry for them. Then, one day, he got an impromptu call to sign some important paperwork.

“Cosgrove had a pretty distinguished career, all things considered. The fact that we remember him for five minutes on the deck of a battleship in 1945, to the exclusion of everything else is pretty unfair to him,” admits historian Pass.

Quick revisions

Back on the deck of the USS Missouri 1945, the international delegations were at a loss for what to do next. Had Canada’s momentary blunder made the surrender invalid? Would they have to consult a Tokyo lawyer? Should they pick up arms and start fighting again?

As chaos began to set in, General MacArthur’s quick-witted chief of staff Richard Sutherland sprang into action. Armed only with his fountain pen he hastily scratched out the now incorrect country titles, painstakingly wrote the titles out himself, and signed his own initials next to the corrections.

Before they had time to protest, Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and General Yoshijiro Umezu were handed their leather-bound capitulation package and whisked off the Missouri’s gangplank, into their waiting boat.

“Now it’s all fine. Now it’s all fixed,” said Sutherland, reassuring the Japanese, officially ending the Second World War and ushering in a new era of peace.

“A mighty air armada passed over our heads, the Marine Band played California, Here I Come and Sidewalks of New York, and everyone was happy, except Japan,” Canadian naval officer George Gayman, who was accompanying Cosgrave, wrote in his journal that day.

Colonel Cosgrave’s botched signature on the Japanese Instrument of Surrender” which brought an end to the Second World War. Photo credit: Wikipedia.

A place in the history books

With that, a monumental mistake basically became a historical footnote.

“It was annoying. It ruined the solemnness of the ceremony,” explains Pass, who insists Cosgrave should be cut some slack. “It was embarrassing. It didn’t reflect well on Cosgrave and perhaps on Canada as well. But it was not terribly consequential. Life went on.”

Life did go on, but unfortunately for Cosgrave, his mistake would follow him across the Pacific Ocean. While the official dispatch to Prime Minister Mackenzie King did not mention his representative’s foul-up, the Allied press made sure to record it.

“Colonel Cosgrove emerges as the feature player in an incident [that]…put a touch of humor in the gravest ceremony of our time,” said the Globe and Mail.

Cosgrave’s infamous mistake would haunt him and define him. He was teased repeatedly, teasing he would grow sick of. But, eventually, he appeared to be forgiven and was able to laugh at himself.

When he passed away in Quebec in 1971, at the age of 80, Cosgrave’s New York Times obituary described him solely as the man who “delayed the conclusion of the armistice” by signing on the wrong line. The Japanese surrender document, with Cosgrave’s (“not so handy”) handiwork, is now prominently displayed at Japan’s Edo-Tokyo Museum for more tourists to see.

But Cosgrave’s letter to a diplomatic colleague about being summoned to the end of the Second War, 79 years ago today is grateful. He takes it all in stride.

“Twill always remain the highlight of my not uneventful career.”