In each EconMinute, Business Council of Alberta economist Alicia Planincic seeks to better understand the economic issues that matter to Canadians: from business competitiveness to housing affordability to living standards and our country’s lack of productivity growth. She strives to answer burning questions, tackle misconceptions, and uncover what’s really going on in the Canadian economy.

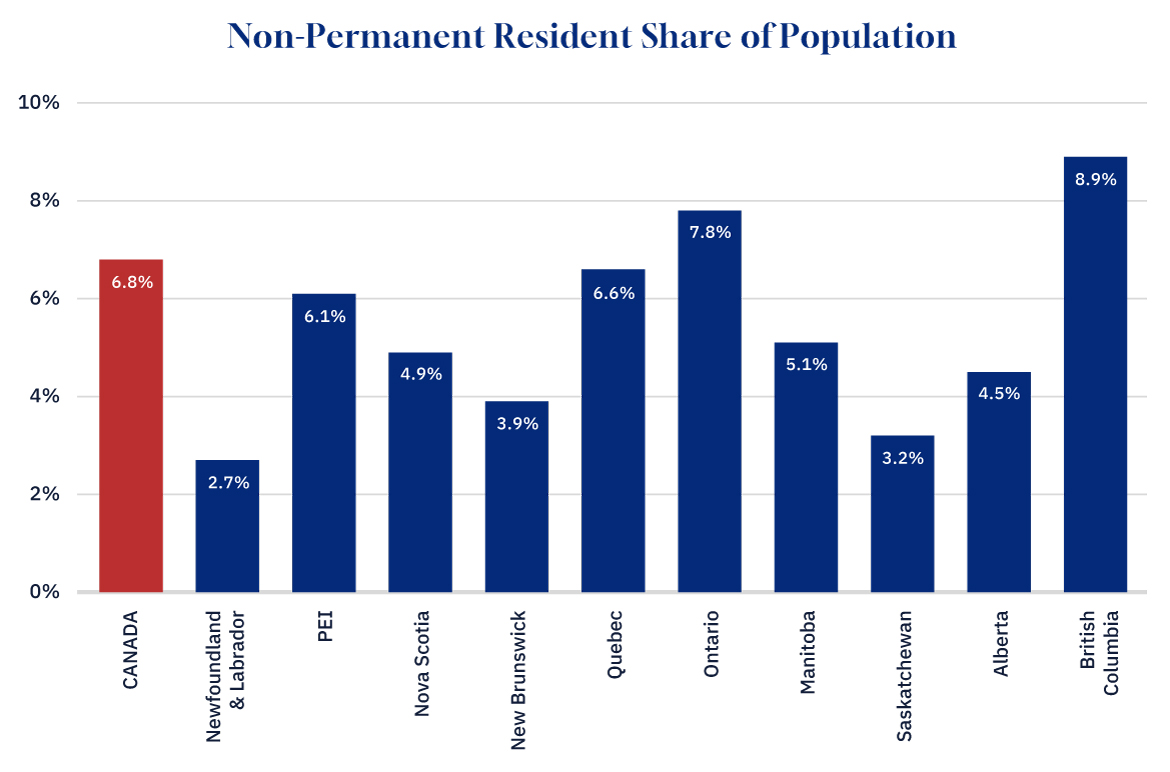

The federal government is under pressure to reduce the number of non-permanent residents (NPRs) in Canada. Specifically, they announced a target for NPRs—foreign workers and students as well as asylum claimants—to account for no more than 5 percent of Canada’s population by 2027.

As of the time of the announcement, NPRs were thought to account for 6.5 percent of the population. Since then, the number has risen slightly (now at 6.8 percent) and many, including the Bank of Canada, have questioned if Canada will reach its target within the given timeframe.

What will it take to reach the target? One consideration is where the imbalance lies geographically. While the target is national, data shows that the NPR population is not evenly distributed across the country, and certain provinces will likely need to see sharper cuts than others.

In particular, three provinces stand out. Though around half of Canada’s provinces exceed the 5 percent threshold, British Columbia and Ontario are both significantly above it (at 8.9 percent and 7.8 percent respectively). Likewise, Quebec comes in slightly below the national average but well above the target at 6.6 percent.

Conversely, smaller provinces tend to fall below the target. Interestingly, Alberta—despite being one of Canada’s larger provinces and experiencing a record-breaking population surge—remains below the target as well.

Of course, the three largest provinces will also weigh more heavily on the national average. To put this in perspective, bringing the NPR-to-population ratio in all other provinces down to just 2 percent (which amounts to cutting the number of NPRs in these provinces in half) would still leave it well above the announced target.

On the other hand, a 30 percent reduction in the number of NPRs in each of the three largest provinces would bring the national average close to its goal (though exact numbers will vary depending on whether NPRs become permanent residents or leave Canada entirely).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Policy changes announced thus far will disproportionately target these three provinces and could go a long way toward meeting the announced target. For instance, the cap on international student permits announced earlier this year will have the biggest impact on Ontario and B.C. Meanwhile, Quebec has made moves to reduce the number of temporary foreign workers in Montreal by placing a pause on new applications in the low-wage stream of the program.

Other policy changes (including greater restrictions on the use of the temporary foreign worker program and a new pathway to transition NPRs to permanent residency) do not have a regional focus per se but will nonetheless have a bigger impact in provinces with more NPRs. All told the current geographical imbalance is likely to level as Canada moves toward the 5 percent target.

This post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.