In each EconMinute, Business Council of Alberta economist Alicia Planincic seeks to better understand the economic issues that matter to Canadians: from business competitiveness to housing affordability to living standards and our country’s lack of productivity growth. She strives to answer burning questions, tackle misconceptions, and uncover what’s really going on in the Canadian economy.

Free trade leads to a lot of good things: from lower prices and more selection for consumers to higher incomes for Canadians. In fact, it’s estimated that incomes are 15 percent to 40 percent higher as a result.

But recent policy developments seem to suggest free trade is out of style.

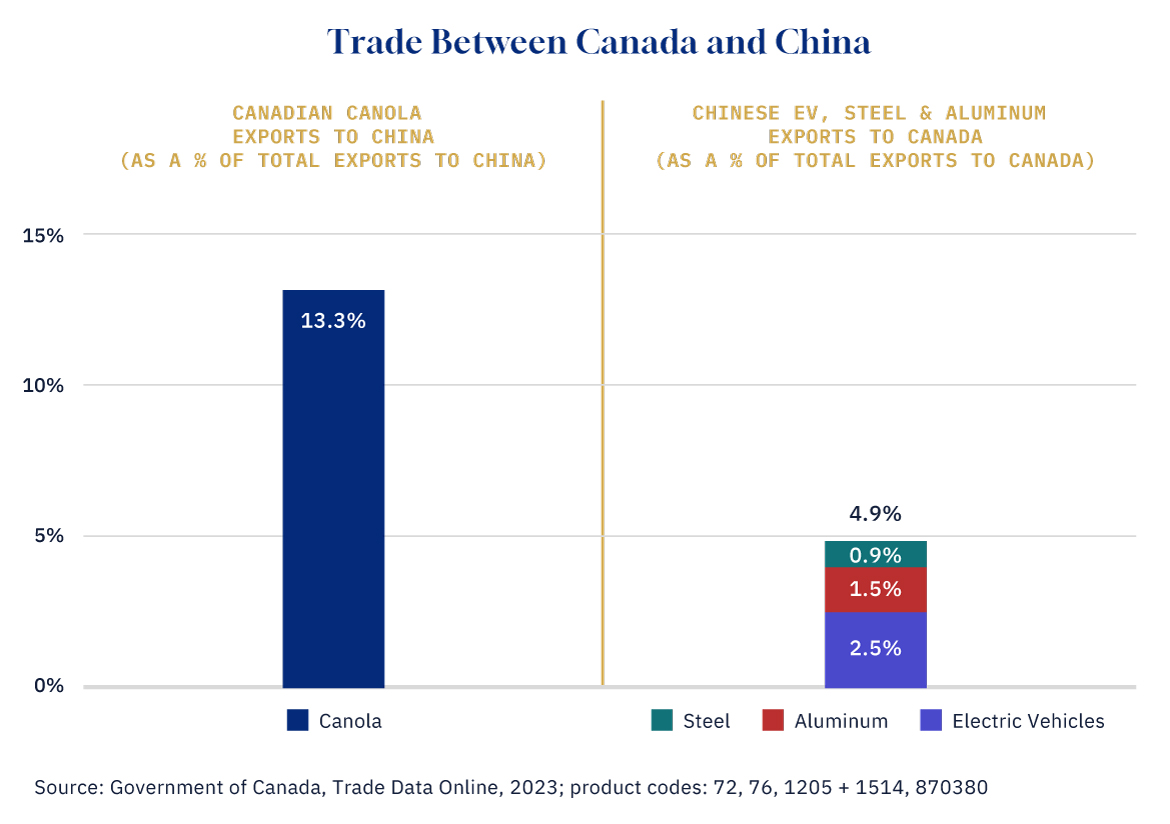

In case you missed it, the Canadian government recently announced new tariffs on imports of certain Chinese-made products, including a 100 percent tariff on electric vehicles as well as a 25 percent tariff on steel and aluminum.

The rationale that it’s viewed as necessary to protect a small but growing EV industry in North America. But there’s also added pressure from the U.S. and EU, that have already imposed similar tariffs domestically, on the grounds that unfair practices are propping up production in China.

Almost immediately, China clapped back with an investigation into canola imports from Canada. So far, no barriers have been put up. But it has nonetheless put Canadian farmers on high alert with the prospect of a classic tit-for-tat trade war.

This would be costly.

The exact cost to Canadian producers will depend on the size of the tariff (or other trade barriers of choice) and how much it deters consumers. For example, would some Chinese customers continue to buy from Canadian farmers despite higher prices?

Nonetheless, the sheer size of the industry suggests the hit to Canada’s economy would be meaningful. Canola is one of Canada’s biggest exports to China, amounting to approximately $4 billion dollars annually or around 13 percent of exports to the country. In fact, in terms of the value exported between the two countries, the canola industry is more important to Canada than EV sales are to China. The Chinese did not select this commodity at random.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

But there could be other cost implications as well. One is the regional impact. As some have pointed out, while the benefits to the EV sector will be concentrated in Ontario, the costs of a potential barrier on canola would be concentrated in the Prairies.

Another is the cost to consumers. Tariffs on China help Canadian producers but hurt Canadian consumers. Some of the most affordable EVs in the world are produced in China. Without them, consumers would be left with fewer options and higher prices for EVs. This is especially important given that all new cars sold in Canada are expected to be zero-emission by 2035.

Whether a decision to restrict trade is the right move likely comes down to politics over economics. Nonetheless, rising tensions and the recent chain of events show decisions to restrict trade—however well-reasoned—rarely come without consequences. These decisions should not be taken lightly.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.