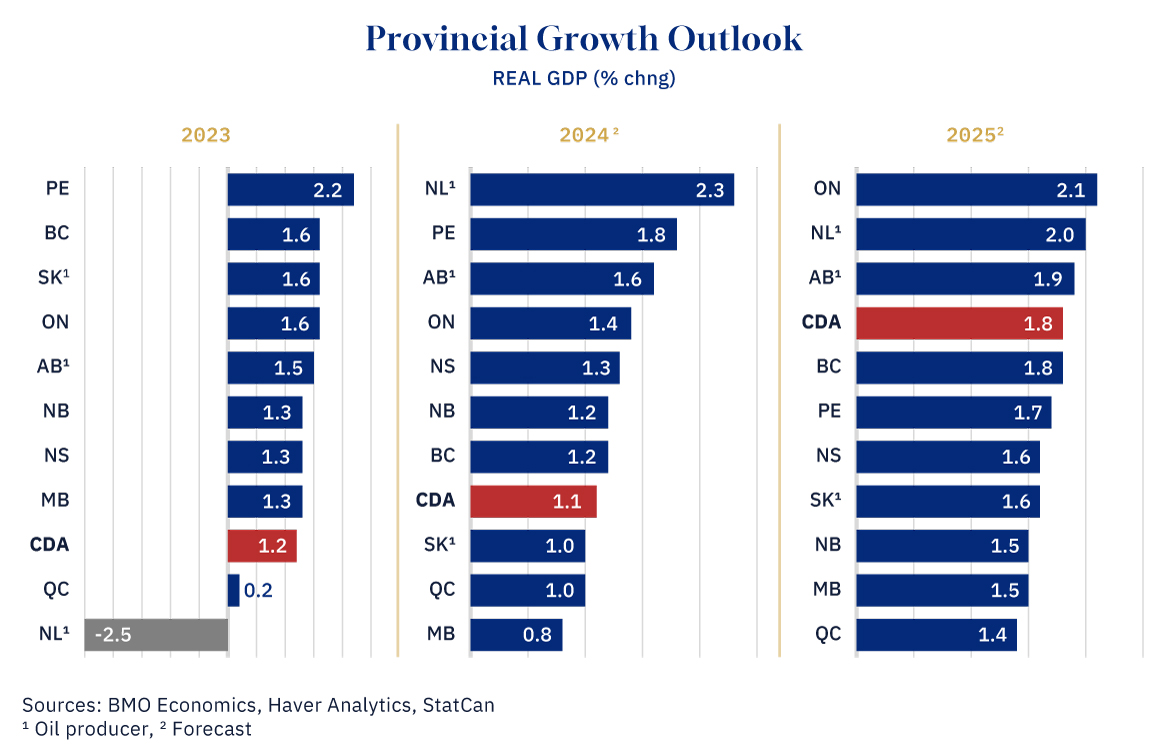

The Canadian economy is growing slowly as past interest rate hikes weigh and the job market softens. Real GDP growth is expected at a modest 1.1 percent this year, while labour supply rises at a brisk pace. That combination has lifted the unemployment rate to 6.6 percent, or 1.8 ppts above the cycle low. Most provinces are running at sub-potential growth rates and seeing per-capita output contract, while the disparity in economic performance across the country is relatively narrow.

British Columbia looks to post growth about in line with the national average through 2025 (Chart 1). The province carries the highest share of residential investment in the country, a sector that is still grappling with high mortgage rates.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Alberta is expected to lead among the larger provinces with 1.6 percent growth this year, as firm oil prices support incomes and demographic inflows surge.

Saskatchewan should underperform slightly at 1.0 percent, while Manitoba’s diverse economy remains steady—these two provinces should benefit from favourable crop conditions.

Ontario’s economy is growing despite the real estate correction. Population growth is a massive 3.5 percent year over year, which is adding to consumer demand and residential investment. The consequence remains stressed infrastructure and high living costs. Real GDP is on pace to grow 1.4 percent this year, with scope to accelerate to 2.1 percent in 2025 as rate cuts are felt more broadly.

Quebec, however, has seen activity struggle, including swings around public-sector strike action. Growth is expected at 1.0 percent this year and a below-average 1.4 percent in 2025. Softer 2.5 percent population growth hasn’t been as big of a driver, nor as big of a stressor. The outcome of the U.S. presidential election could also have significant implications for Central Canada, and eyes will be on any changes in the trade file.

Atlantic Canada continues to grow at a solid clip, largely due to population growth—both from international immigration and interprovincial in-migration. Most of the region should see growth around prior-year rates in 2024 as residential investment and consumer spending hold firm.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

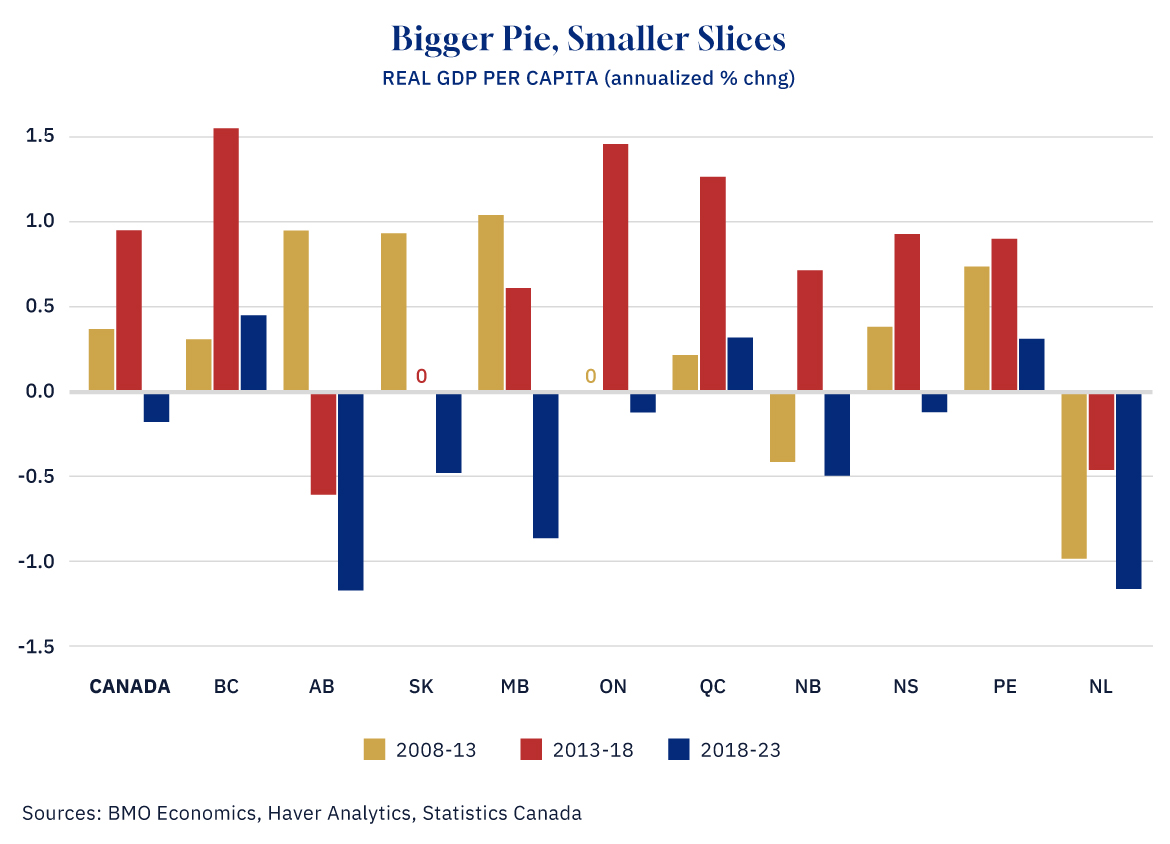

One takeaway for the group is that, while each provincial GDP pie is getting bigger, the slices (i.e., per-capita output) are getting smaller (Chart 2). Per-capita output has contracted across seven of 10 provinces over the past five years, a stark change from prior periods. Note that each period involved a major shock, be it the financial crisis (2008-13) or the oil boom/bust (2013-18).

This article was originally published at BMO.