The following is the second installment in a multi-part series tackling Canada’s housing and immigration crises. The series will focus on their root causes, intertwined nature, and potential solutions. You can read part one here.

The first article of this series laid out the basic arithmetic of Canada’s current housing crisis—ill-advised levels of immigration far above Canada’s capacity to build sufficient housing to accommodate the consequent rapid increase in population—and pointed out that there remains an undiminished belief that the solution to this is to be found on the supply side, and that a set of policy changes will allow Canada to build significantly more houses in the next eight years than it has in the previous eight years.

Part one ended with the provocative statement that this belief is a dangerous delusion that, if it continues to animate immigration and housing policies, will do further damage to Canadians’ standard of living and quality of life.

The nub of the argument that Canada can build its way out of its housing crisis is that Canada is a large country, and we should be able to build sufficient housing for the country’s growing population but for overly restrictive municipal zoning and permitting requirements.

Although it is not always stated explicitly, it is at least strongly implied that these restrictive requirements are driven by the selfish “NIMBYism” of those who have already secured suitable housing for themselves.

The only problem with this argument is that it ignores the facts on the ground.

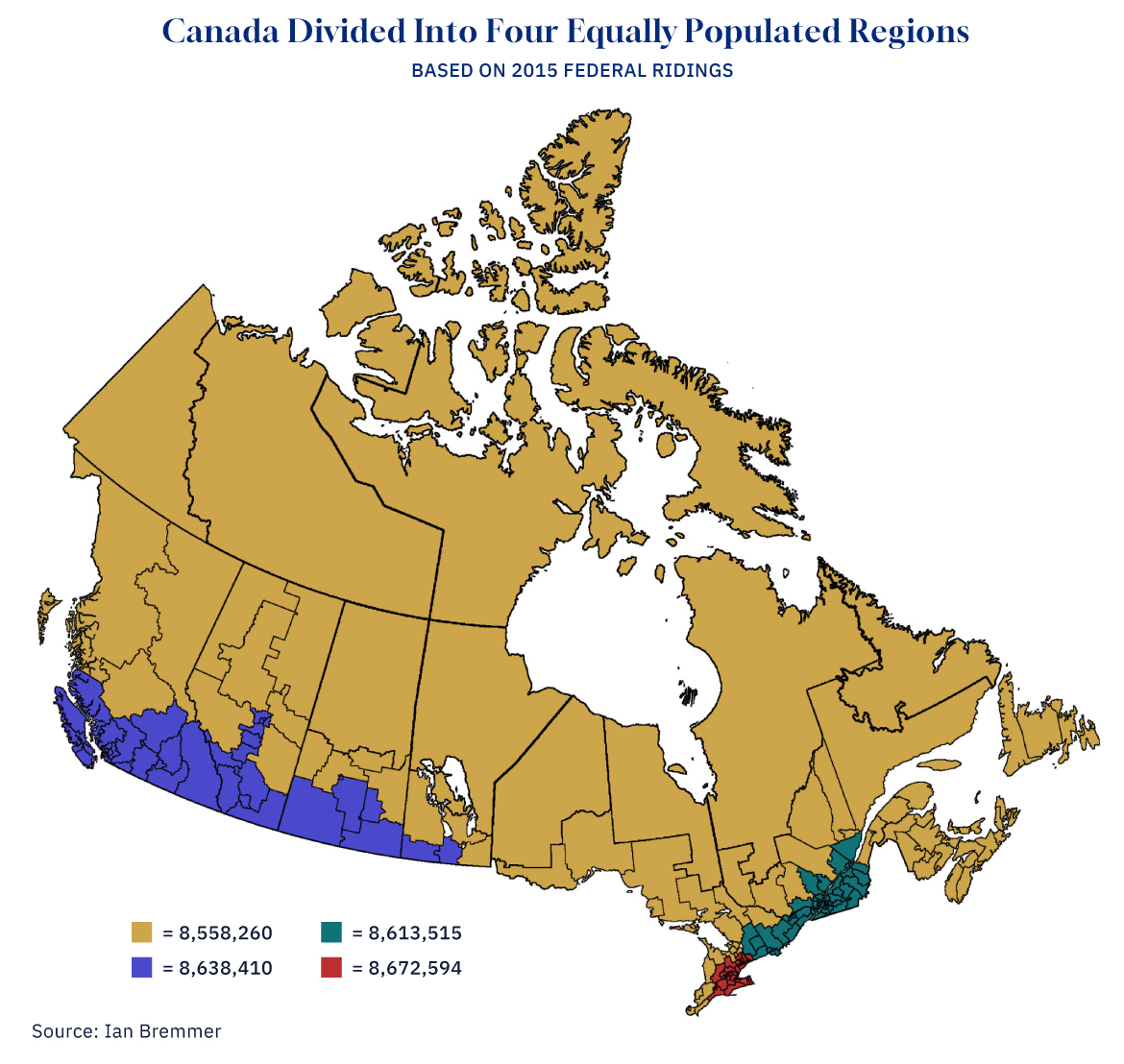

Yes, Canada is a large country. But when it comes to where people want to or need to live, not so much. Our population is concentrated in a very small portion of our land mass. A flavour of this is provided by the map below, which divides Canada into four “regions” with equal populations. This map is based on 2011 population numbers, but if it were redone with current population numbers the red, green, and purple areas would all shrink, as Canada’s population growth has continued to concentrate in its major metropolitan areas.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

It is no doubt true that it would be relatively easy to find space to build houses in that big yellow area. The reality is that very few new Canadians choose to live in that big yellow area. In fact, the overwhelming majority of new Canadians choose to live in very tiny pieces of the other areas.

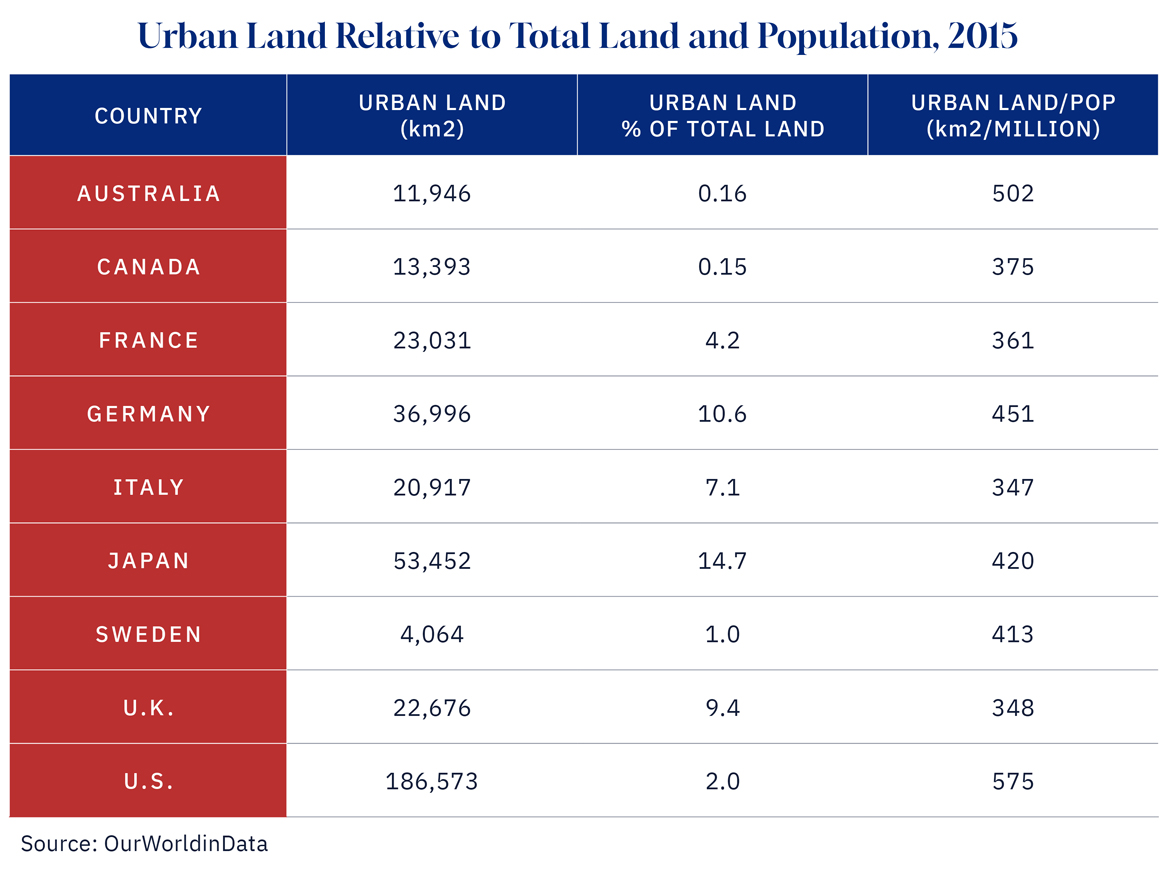

Let’s look at this from an international perspective. In the table below, Canada is compared to the other G7 countries, as well as Australia and Sweden,Australia is arguably the country most similar to Canada in terms of geography, economic structure, and relative concentration of population. Sweden has often been held up as a comparator/idealized mode for Canada on many socio-economic dimensions. in terms of total urban land in absolute terms and relative to overall land area and total population in 2015.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

In addition to showing what a small percentage of Canada’s land base is urban, it also shows the fact, perhaps surprising to some, that Canada has less urban land per million people than most of the countries on this list. In essence, Canada is “urban land poor.” It is in particular worth noting the discrepancy between the U.S. and Canada. Because of our proximity to the U.S., it is only natural that Canadians will benchmark their housing availability and affordability against that of Americans. The U.S. has 50 percent more urban land per person than Canada does. And keep in mind this discrepancy will have grown since 2015 as Canada’s rate of population growth has greatly exceeded that of the U.S. since then.

Well, couldn’t we just expand municipal boundaries and grow our urban land base? To some extent, Canada has been doing this over time, but the ability to do this around our major metropolitan areas has become increasingly constrained because of land use policies—for instance, the agriculture land reserve in British Columbia and the greenbelt in Ontario—that make such conversions less and less politically doable.

The notion that we could insist new Canadians live predominantly in the yellow parts of the map above doesn’t make any sense economically as economic activity is increasingly being concentrated in major metropolitan areas. In any case, there would be no mechanism by which Canada could insist that the newcomers stay in the yellow, even if their initial entry permit required them to start their life in Canada there, which would not survive a Charter challenge to the courts.

“None of that is problematic,” say the supply siders, “just densify!”

In part three of this series, we will see why that proposal is less of a solution than its proponents claim.