Canada has a major economic opportunity in the global low-carbon economy, if it gets its climate and energy policies right. Those policies should be informed by principles like leveraging the ingenuity of markets and free enterprise, limited government, and respect for provincial jurisdiction. The following article is the latest installment of The Hub’s series sponsored by Clean Prosperity exploring the why, what, and how of conservative climate policy.

The phenomenon of ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing has sought to move capital away from higher-emitting (or “brown”) firms and into low-emitting (or “green”) ones.

Inevitably, there have been unintended consequences. A few are worth noting.

The first is that it has generally made heavy emitters perform worse, rather than better. As groundbreaking research by Samuel Hartzmark and Kelly Shue shows, starving heavy polluters from affordable capital means they can’t invest in reducing emissions. Rather, they tend to become short-termist, focused on reaping as much profit as possible before being squeezed out, instead of investing in processes and assets that would reduce their emissions but take years to pay off.

While starving brown firms of affordable capital often increases, rather than reduces emissions, providing green firms with more accessible capital leads to minimal benefits. That’s because green firms, by definition, don’t have a lot of emissions to reduce.

As an example, should Sunlife, a Canadian insurance firm that is highly ranked on sustainability indices, reduce its emissions by 100 percent, and achieve net zero, the company would save about 41,000 tonnes of CO2e.

If Cenovus, an oil sands company, knocked 6.2 percent off of its emissions (which it did between 2021 and 2022), it would save 1.2 million tonnes of CO2e.

ESG investing rewards the former rather than the latter. This is counterproductive.

The second is even more perverse. Brown sectors such as coal and oil that are shunned by ESG investors have become more attractive for private investors and state-owned enterprises who aren’t affected by ESG performance; and less attractive for publicly owned companies whose valuations are.

Similarly, many brown industries have been incentivized to move their production to jurisdictions and companies with lower (and thus less expensive) environmental standards. The upshot of all this is that brown firms are more likely to choose structures and jurisdictions where emitting more costs less.

The phenomenon has a name: carbon leakage. And it means global emissions are more likely to be relocated than reduced by onerous environmental standards.

A third and related phenomenon is that climate-conscious Western nations have lost a lot of their industrial capacity in heavy-emitting sectors, as these have set themselves up in less environmentally stringent nations. This is a huge problem because we actually need heavy-emitting sectors: oil refining, metal smelting, steelmaking, resource extracting, chemical manufacturing, and many more.

Canadian production in copper, nickel, cobalt, and graphite, for example, have all declined substantially in the past decade. Canada has just one copper smelter left, in Quebec. China has come to dominate the processing of a variety of critical minerals and chemicals, supported by their cheap industrial heat and power from burning coal.

It is hard to imagine the reshoring of energy-intensive material manufacturing aligning with Canada’s Paris commitments. But this imposes a direct tradeoff with our economic security and entrenches dependence on China.

Canadian best-in-class

Much of our current Canadian climate policy has focused on reducing domestic emissions by making our heavy emitting sectors smaller and uncompetitive, for example by proposing emissions caps for oil and gas production and fertilizer use.

This strategy is resulting in the unintended consequences outlined above: carbon leakage, offshoring of heavy industry to jurisdictions with weaker regulations, and vulnerable supply chains.

A conservative climate policy—one that confronts rather than ignores those realities—could better address the nation’s climate, economic, and security goals by doing one simple thing: boosting Canadian commodity exports across all sectors.

That’s because Canadian commodities outperform global averages in GHG intensity in almost all cases, owing to a variety of factors: our clean electricity grid, robust environmental standards, and high-quality resources amongst them.

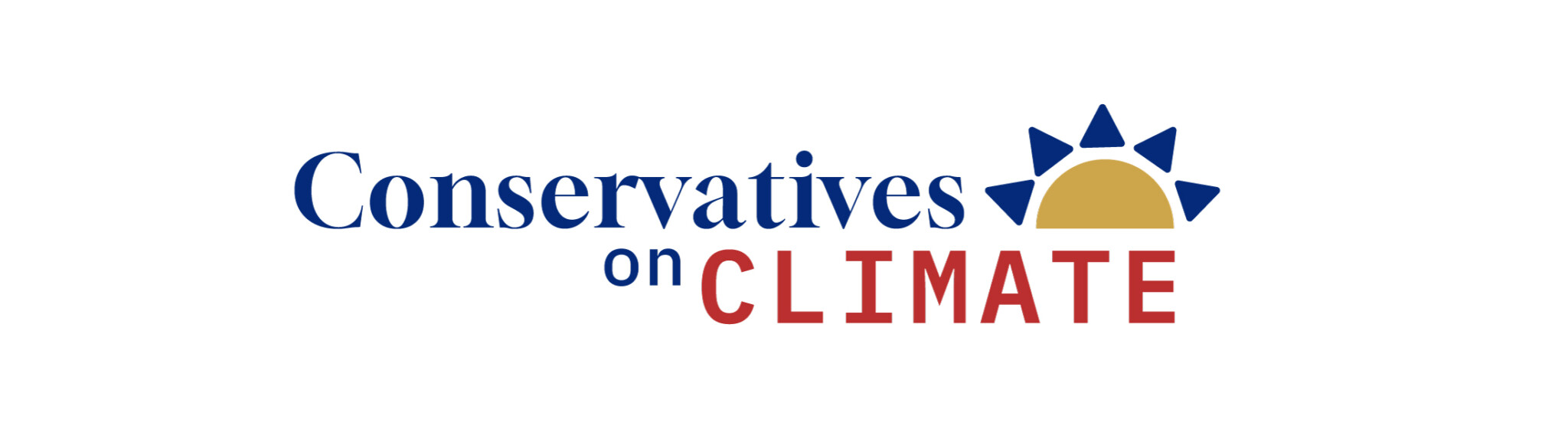

In mining, Canadian commodities across almost all types have lower carbon intensities than the global average, and many are world-leading (see figure 1).

Aluminum, copper, gold, and nickel are in the top performing decile for GHG intensity amongst their peers. Our potash is produced with 50 percent lower GHG intensity than its competitors. Even Canada’s metallurgical coal—an essential component in steel-making—has the lowest GHG intensity of any global producer.

Figure 1 E1 GHG emissions—country percentile position, by commodity. Credit: Skarn Associates. Source: Canadian Mining Journal 2021. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

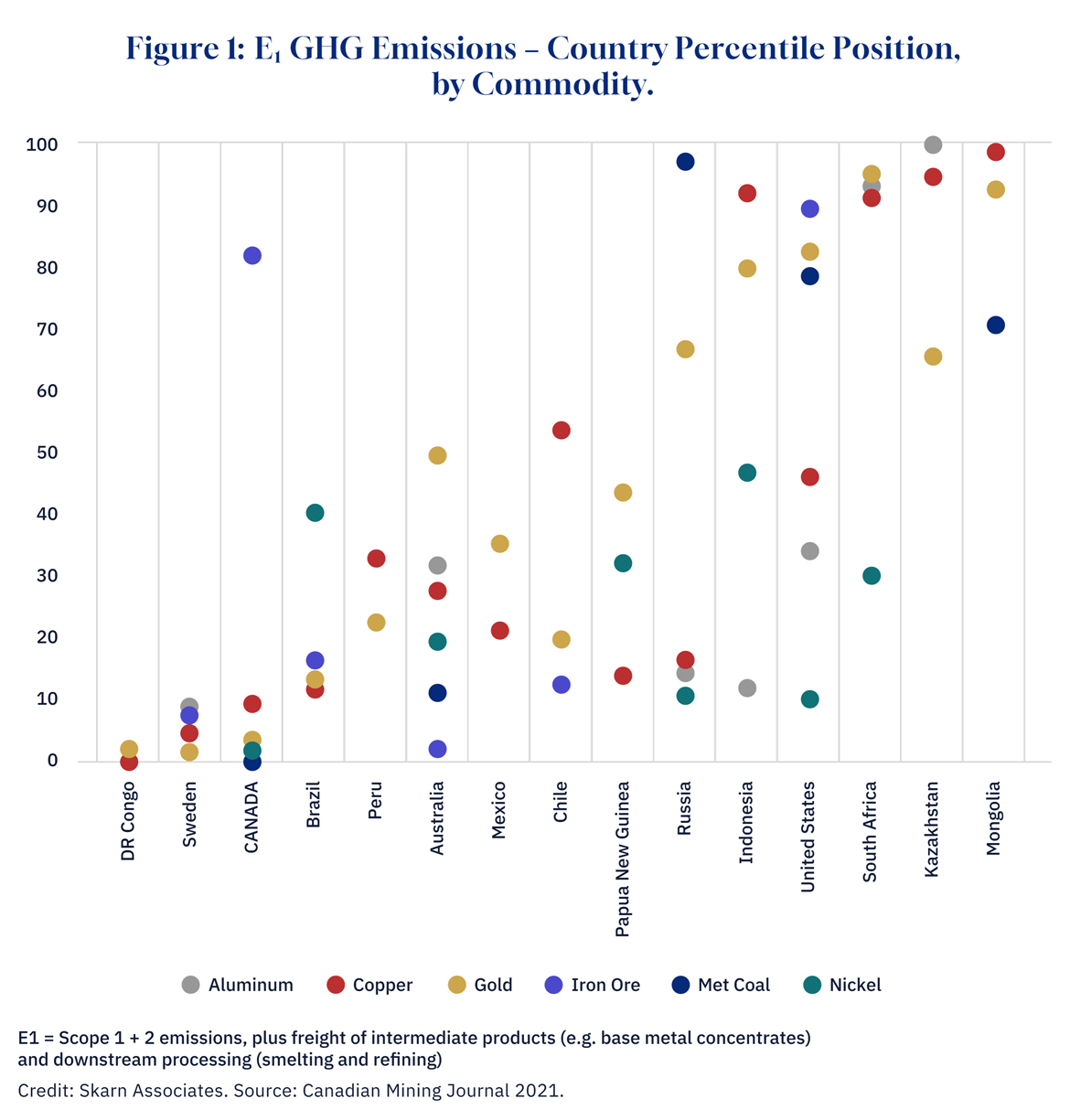

The same applies in agriculture. According to the Global Institute for Food Security, Canadian products have a fraction of the global average carbon intensity for staples including field peas, durum wheat, lentils, canola, and non-durum wheat (see figure 2 as an example). This is owing largely to genetics, crop rotation, efficient fertilizer application, and zero or minimal tillage practices in Western Canada.

Figure 2 CO2 intensity of non-durham wheat. Source: GIFS 2023. Comparisons for all agricultural commodities listed above are available from this source. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Finally, natural gas and—yes—even oil production in Canada compare favourably to their peers.

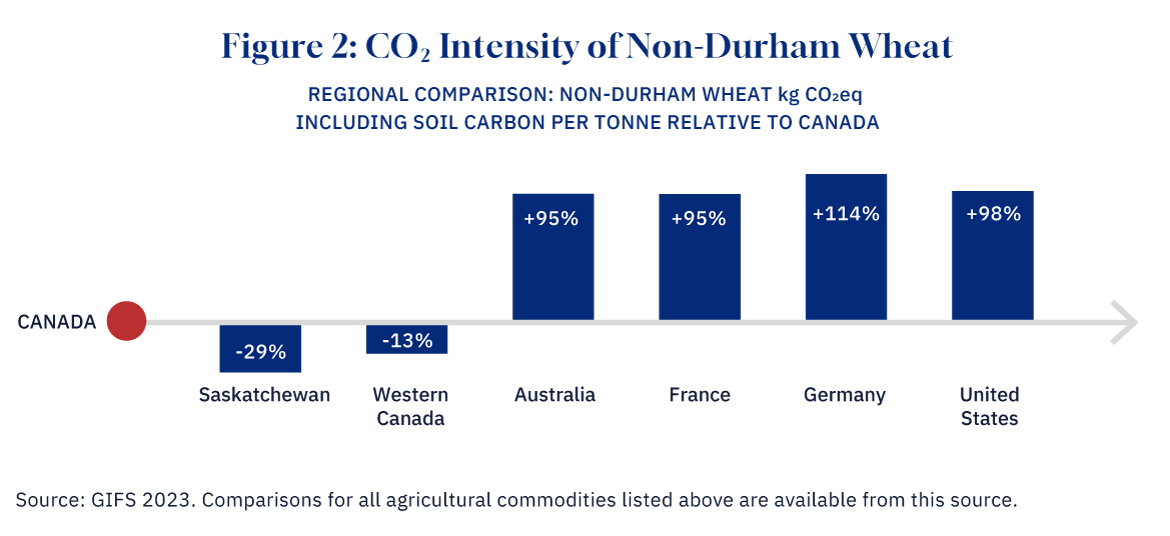

Canadian LNG exports will be amongst the lowest emitting in the world. That is because the planned LNG export terminals in British Columbia largely benefit from access to clean hydroelectricity for the energy-intensive process of cooling natural gas until it is a liquid; and from cooler ambient temperatures at the facility site. LNG Canada, Woodfibre LNG, and Cedar LNG are all expected to export amongst the cleanest LNG on the planet (see figure 3). Upstream, Canadian natural gas also enjoys progressive and world-leading methane management that has further reduced emissions intensity.

Figure 3 CO2 tonnes emissions intensity by source of LNG. Credit: Jerome Gessaroli, Macdonald-Laurier Institute 2024 Sources: LNG Canada; Cedar LNG Project Environmental Assessment Certificate Application; Canadian Energy Centre. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

While some conventional Canadian oil production has relatively low GHG intensity, the oil sands are more complicated. Although there has been significant progress in reducing the carbon footprint of each oil sands barrel, resulting in a 23 percent lower emissions intensity since 2009, on average oil sands production is about 50 percent higher emitting than the global average.

However, the apples-to-apples comparison for the Canadian oilsands isn’t light, sweet crudes from Norway or Saudi Arabia. It’s with other heavy oils. That’s because the refineries in the United States (and increasingly Asia) that accept Canadian crude are optimized to process heavier oils and produce a range of petroleum products that rely on the unique chemical properties that heavy oil possesses. Light, sweet crude is not interchangeable in practice with heavy, sour crude.

The range of carbon intensity for global crudes is enormous. When compared to similar crude grades, Canadian heavy oil compares relatively favourably. According to S & P Global analysis, Canadian oil sands operations have carbon intensity values of between 43.6 kgCO2e/boe and 119.8 kgCO2e/boe. The Unites States’ domestic source of heavy oil, California’s medium to extra-heavy San Joaquin oil, has 177.9 kgCO2e/boe. And although sanctions are often applied to Venezuelan’s heavy oil owing to President Maduro’s dictatorship, it has the world’s largest reserves of oil and is a natural competitor for Canadian heavy oil. Their prolific Orinoco Belt has a whopping carbon intensity of 1,460 kgCO2e/boe.

This is not to say that the Canadian oilsands can’t and shouldn’t reduce their carbon intensity, and with Pathways Alliance there is a credible plan to do so. But the obvious alternatives to Canadian heavy oil in oil markets, particularly the American one, are worse.

Figure 4 Comparison of Production Volumes and Production GHG emission intensity for Gulf of Mexico and Other US Regions and Other Countries Crude Oil across all API gravity categories. Source: NOIA 2023. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

A conservative climate policy—one that prioritizes reducing global emissions over meeting national targets—should not make Canada’s heavy emitting sectors smaller; it should make them better. That means keeping our high environmental standards and industrial carbon pricing; but not at a level where it depresses Canadian production and competitiveness.

As a rule of thumb, any Canadian commodity that performs above the global average for GHG intensity should be preserved, because offshoring production would lead to higher global emissions. As a matter of climate policy, our focus should be on supporting Canadian products to be best in class (e.g. in the top performing quartile globally for emission intensity) rather than phasing them out.

The caveat here is that as other producers reduce their emissions through various technological advances, Canadian producers would have to remain a step ahead of their peers to remain that top performer. A race to the top, rather than the bottom.

Global energy and climate systems are complicated. What makes sense in reports and in conferences often doesn’t make sense when tested in the real world.

Getting rid of Canada’s brown sectors is one of those ideas that may look good on paper but is absolutely counterproductive to reducing global emissions in real life. A conservative climate policy should focus on making Canada’s heavy-emitting industries the best in the world, not the smallest.