This August, Ontario’s Health Minister, Sylvia Jones, announced that the Ford government would close drug consumption sites within 200 metres of schools and childcare centres. In making the announcement, Jones explained, “Continuing to enable people to use drugs is not a pathway to treatment.”

Her government’s shift in policy followed a string of blows aimed at Canada’s harm reduction policies, which were increasingly prioritized over the last decade or two to tackle the country’s drug crisis. In April, NDP Premier David Eby, historically a supporter of these policies, felt the need to walk back B.C.’s decriminalization trial halfway through the program following outcries from the community, who expressed serious concerns about what they were seeing.

More recently, Eby, against more mounting pressure from his constituents amidst an impending election campaign, went on to order a review of drug-use “vending machines” (some of which—astoundingly—had been placed outside of a hospital where addicts may be receiving treatment). Eby would make a much bolder announcement in September, when he shared that the province would place those who are severely addicted into involuntary treatment, adding “This…is the beginning of a new phase of our response to the addiction crisis. We’re going to respond to people struggling like any family member would.”

Though the Ford government’s reversal of the decision to place drug facilities near children’s centres addressed specific concerns, Jones’ comment seemed to hint at a much larger issue: that the bedrock of our drug policy, which prioritized offering safer ways for addicts to use hard drugs over treating their addiction, has been an abject failure.

In fact, Canada’s drug epidemic has reached such critical levels that it has attracted international attention. This past July, two journalists based out of the U.K. produced an investigative piece for the Telegraph highlighting the increasingly dire situation unfolding in Vancouver. Providing a glimpse into the city’s deepening drug crisis, they published heart-wrenching photos of strung-out addicts — some on the verge of an overdose and clinging to life — and went on to explain to their non-Canadian readers that “…a landmark experiment to decriminalise the possession of certain drugs in public — including fentanyl, heroin, cocaine, methamphetamines, and ecstasy — has allowed an opioid crisis to take hold that surpasses even the epidemic in the United States.”

Controversial as it may be to some, it is indeed a stark reality — a once vibrant, safe, and beautiful city has fallen victim to a disease that no one seems able to get a hold of.

The Telegraph exposé came at the heels of yet another troubling report out of London, Ontario, where police released details stemming from a months-long investigation that seemed to further discredit some of the harm reduction tactics being employed around the country. This time, centering around the city’s “safe supply” program, a scheme where doctors prescribe hydromorphone (an opioid), usually in 8-milligram pills, to people who are likely to use illicit street drugs like fentanyl. After a six-month investigation that led to 247 charges against 50 people, police made a damning announcement: a shocking amount of the drugs found had been diverted from safe supply programs, ending up in the hands of drug dealers across London and beyond.

The announcement sent a clear message; safe supply wasn’t so safe after all. But this, together with the Telegraph article, didn’t sit well with harm reduction advocates, nor journalists who consider themselves to have a pulse on the issue. In fact, the Toronto Star published an opinion article shortly thereafter, by journalist Manisha Krishnan, that slammed the Telegraph story while strongly defending safe supply measures: “Some safe supply is being diverted, but there is no evidence that it’s led to more deaths or teens forming new addictions,” wrote Krishnan. She linked to a report from the Office of the Provincial Health Officer of British Columbia to back up her claims — except, unfortunately, it doesn’t. When reading the report, what it actually states is this: “Some diversion is occurring; however, the extent and impacts are unknown.”

Krishnan also failed to highlight one other significant caveat published within the report: “Evidence for PSS (Prescribed Safer Supply) is promising…but not at this point strong enough for this intervention to be described as fully evidence-based…The evidence scan demonstrates that more needs to be done to investigate the potential for harm at the population level.”

Oops.

Additionally, although the data indicates there has not been an increase in Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) diagnoses amongst youth, or in any age group, since PSS launched in 2021, the report also implies that the data is a bit shaky: “…primary data collection with youth is limited aside from a pre-publication analysis from the At-Risk Youth Study. Additionally, policing data…have not been systematically explored.”

Ultimately, Krishnan seems to spreading what she claims to be debunking in her article — more misinformation.

A woman walks past a person using a glass pipe to smoke drugs in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, August 31, 2021. Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press.

An epidemic killing more young people than COVID-19

As of 2021, one out of every four deaths in young people in Canada was opioid-related; a brutal and infuriating statistic, particularly on the heels of a pandemic that was treated as the biggest threat to public health in recent history. In B.C., opioid overdoses have become the leading cause of death for people aged 10–59 and now account for more deaths than homicides, suicides, accidents, and natural diseases combined.

The beginning of the end

In 2003, shortly after celebrating my eighteenth birthday, I moved away from my hometown to attend the University of Toronto. It was there, in that much larger city, that I first witnessed homelessness at scale and the societal ills that hard drugs and mental health issues can inflict on a place. And though not yet everywhere, there were small pockets in and around the city that served as host to many homeless and drug-addled youth (with only a punk-ish edge distinguishing them from the hipsters of the city’s early aughts scene). Yet there was always a feeling that, if they chose, those struggling with drugs could access the help they needed and ultimately get themselves out of that situation. And indeed, many of them did.

Today, however, what was once considered a drug problem stemming from the colliding rise of youth rebellion and medical system failures has turned into a full-blown epidemic — one that has infiltrated nearly every city and small town across North America. Gone are the days when the sight of someone visibly high on drugs would stop you in your tracks. Instead, we simply glance over our shoulders, shake our heads, and keep on walking, accepting this heartbreaking and increasingly familiar fixture in our lives.

Today, many of our downtowns resemble scenes from The Walking Dead. City streets are lined with addicts. We have a society in which grown adults feel comfortable shooting up on the front steps of our elementary schools. Many of our beautiful ravines and parks have been converted to dilapidated campgrounds littered with haphazardly built tents, garbage, and human waste strewn about.

So, what happened?

“It’s multifaceted. There’s a lot of trauma. Health-care services are on the brink. The drugs are stronger and more addictive.; They can’t afford housing, so now they’re out on the streets.”

These are the usual replies when discussing the accelerating drug epidemic with our leaders. Yet, people have always had trauma, of course, and though most public services have gone downhill in recent years, it seems the main reason addiction services are falling short is simply because of the increasing number of people who need them. Mary Bartram, policy director at the Mental Health Commission of Canada, told CBC News in March 2023 that “There’s no way that increased investment has caught up with the increased level of need.”

That said, some things are for certain: the drugs have gotten stronger, and people seem to be getting more addicted. But when and how did the drug epidemic really start?

A man using a rolling walker walks on the street past tents setup on the sidewalk at a sprawling homeless encampment on East Hastings Street in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, on Tuesday, August 16, 2022. Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press.

Go West

In both Canada and the United States, an influx of tent cities first appeared around the turn of the centure along coastal cities on the West Coast, most notably in California, Oregon, and British Columbia. Ease of access to shipping ports along the Pacific Ocean, ideal for trafficking, along with a laissez-faire attitude towards recreational drug use, made this region a hotbed for drug users who were looking for a more accepting place to settle. In 1997, the Vancouver-Richmond Health Board declared the rise in hard drugs a public health emergency, and the voices calling for supervised injection sites and heroin-assisted treatment programs grew louder.

In 2000, the San Francisco Health Commission made harm reduction — which advocates making it safer to use drugs rather than criminalizing those who use — an official public health policy. Following step one year later, the City of Vancouver’s drug policy coordinator authored a report called ”A Fours Pillar Approach to Drug Problems in Vancouver,” which recommended harm reduction as a key priority of drug policy strategy. This report would ultimately go on to inform drug policy approaches across Canada.

Over time, the public watched hesitantly as more harm reduction policies were rolled out, thanks to advocates who deemed them critical in the fight against addiction. These ideas would lead to conversations about the decriminalization of hard drugs and, eventually, the opening of so-called “safe” or supervised injection and supply sites across the country. Indeed it was in 2003 when Vancouver became home to North America’s very first supervised injection site. Reasonable concerns were raised, and the public questioned whether these tactics might actually encourage more drug use. However, activists were quick to silence dissenting voices while doubling down on their claims that these policies would save lives and that the benefits to addicts would outweigh the costs to society.

In 2005, a heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) trial began in Vancouver and Montreal, but by 2007, Stephen Harper’s newly elected Conservatives had already introduced their National Anti-Drug Strategy. This seemed to indicate an end to the HAT programs and a pause to similar policies being implemented throughout the country. Nonetheless, a second HAT trial opened its doors in Vancouver at the end of 2011. But by 2013, it became evident that they might be forced to close their doors for good. This prompted a handful of the program’s participants, along with Providence Health Care of British Columbia, to file a Charter challenge against the federal government. However, when the Liberals were elected in 2015 they withdrew the case and the program continued.

When other cities throughout North America began to adopt similar harm reduction practices — coinciding with the introduction of new and far more dangerous narcotics hitting the market — the drug problem spiralled.

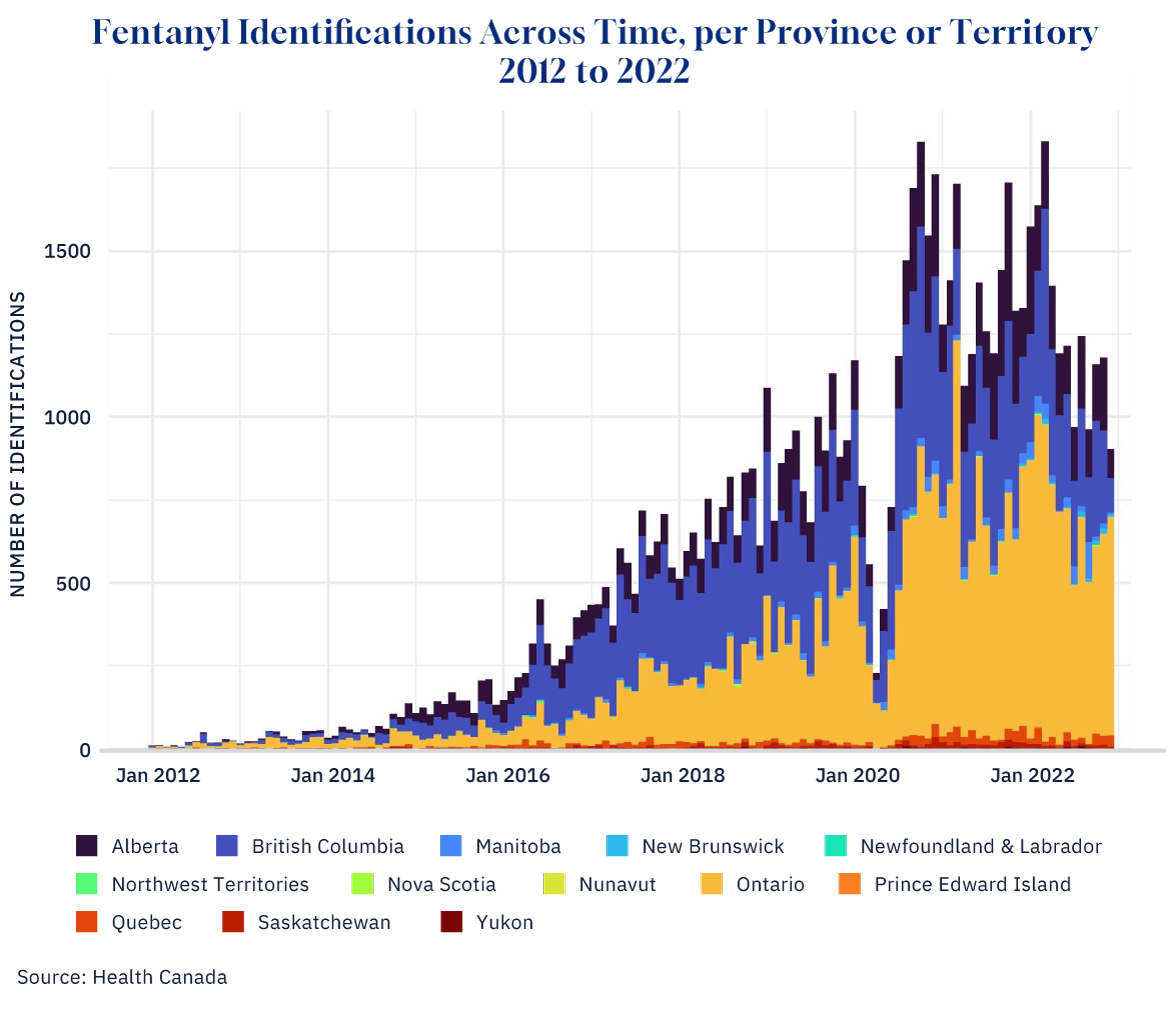

Source: Health Canada. Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The fentanyl effect

First detected by police in 1989, fentanyl hit the streets in a bigger way around 2012, eventually eclipsing the damage done by its opioid predecessor, oxycodone hydrochloride, most commonly sold under the trade name OxyContin. A pharmaceutical, OxyContin was found to be overprescribed by several doctors across North America, resulting in not only an unprecedented level of prescription drug abuse but also unfettered black-market circulation. This led many users to escalate into harder drugs, like heroin, kickstarting an opioid crisis that snowballed in the early 2000s.

Though both drugs are used to treat pain, fentanyl is significantly more potent than OxyContin and far more deadly. With fentanyl registering at 20 to 40 times more potent than heroin (and 100 times more potent than morphine), it has not only become the drug of choice for many chronic drug users, but it also puts their risk of overdose exceptionally high.

While fentanyl is prescribed in many countries around the world, the opioid crisis has particularly hit the U.S. and Canada, affecting mostly young and middle-aged adults. Although this has most often been blamed on system-wide failures of the pharmaceutical and health-care industries (which enabled a profit-driven quadrupling of opioid prescribing) the policies that have allowed this crisis to not only continue but reach such critical levels are deserving of scrutiny.

Indeed, despite overwhelming consensus acknowledging that the overprescribing of pharmaceuticals led to this crisis, bureaucrats continue to stand firmly behind experts who consider the introduction of a “safe supply” an effective way to temper it. (Yes, you read that right; we’re attempting to mitigate a crisis stemming from the over-prescribing of opioids by prescribing more opioids).

Despite this consensus, Krishnan’s article makes a startling claim—that “decades of prohibition have impacted the current fentanyl crisis.” Her rationale is that the 2010s crackdown on prescription pain pills meant that many were left with no other option but to turn to heroin (presumably as it was easier to come by). But this leaves out a key part of the equation: if prohibition did fuel the current crisis, then why did we see such a dramatic rise in fentanyl use at the exact time our drug policies began favouring harm reduction over criminalization?

It’s just business, baby

It would be hard to argue that the increased regulation of pharmaceuticals led to the fentanyl crisis. Ultimately, fentanyl is cheaper and easier to make than other drugs. It’s also odourless and tasteless, making it easier to traffic. Additionally, because it goes undetected when mixed with other narcotics, and so many users first ingest the drug unknowingly which then fuels their addiction. In the end, it seems much more likely that our policies have helped foster an environment where the drug trade could flourish; de-regulation and newly sanctioned supply channels meant dealers could build smarter networks within the system, allowing for greater economies of scale and more customers.

In fact, a recent article in the National Post suggests just that; in April, a report was leaked that had been commissioned by B.C.’s top doctor, Bonnie Henry. Written by American drug policy expert Jonathan Caulkins, the report examined the “economics” of safer supply diversion. But, as the article uncovers, it presented some troubling conclusions. Ultimately, Caulkins raised serious concerns about “the impacts that cheap or free safer supply could have on national and international drug markets,” with Caulkins concluding that “resourceful smugglers” would likely procure these drugs and resell them in other jurisdictions where they command a higher price.”

The drug policy expert was particularly concerned about how profiteers may benefit from the distribution of “safe fentanyl,” not only because it’s in such high demand across North America, but also due to the fact that it’s “compact and easy to smuggle.”

Worse though, the article suggests that the Provincial Health Office attempted to bury the contents of the report, presumably due to the implications it may have on current drug policies—the same ones that have evidently made drug trafficking easier, contributing to a multi-billion-dollar international narcotics industry and, undoubtedly, creating a slew of new millionaires in the process (lucky for them, clamping down on money laundering has never been Canada’s strong point).

Beyond speculation, this theory holds some weight. A recent interview with U.S. State Department official David Asher, published in The Bureau, offers insight into Canada’s illicit drug trade. Asher discusses how U.S. government investigations of TD Bank revealed that Toronto and other Canadian cities are host to the global command and control of fentanyl money laundering. North America seems to be battling what he calls a “reverse opioid war,” in which Chinese Triads in Canada have been co-opted by the Chinese Communist Party to facilitate global money laundering and drug trafficking. “We should be treating this like it’s a new type of hybrid war. We are losing citizens like we haven’t seen since World War II,” said Asher.

He also criticized the Canadian government for inadequate cooperation in fentanyl trafficking and money laundering investigations, suggesting “political and financial influences are hampering effective law enforcement” and that “failure to disrupt these networks is contributing to the ongoing fentanyl crisis.” In other words, it seems government policies may be fueling Canada’s drug trade on multiple fronts.

Tents are seen on the sidewalk in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver, on Tuesday, August 16, 2022. Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press.

The tides are turning

Alberta is already beginning to see some success through what former premier Jason Kenney calls “an alternative to the single-minded obsession” with harm reduction.

In a podcast interview with The Hub in September, Kenney shared that Alberta is instead ensuring that those suffering from addiction can access seamless opportunities to “detox into long-term treatment.” These will not be day programs situated in areas “where they’re surrounded by their dealers and their addicted friends”, said Kenney, emphasizing the need to be “removed from those destructive environments.” He says they’ve already made huge investments and have seen “tremendous integrations between police, addictions services agencies, other social services, homeless shelters and…provincial and municipal governments.”

“It’s going to be a long fight, and we need the Feds to be on board with this,” said Kenney.

Though the Caulkins report fiasco and the announcement from B.C.’s premier to re-criminalize drug use in public spaces (despite being only halfway into their three-year trial on decriminalization) were early indications of shifting attitudes, the reality on the ground did not seem to persuade all policymakers. In fact, some seemed more committed than ever to pursuing the same failed strategies. Just as the stories out of Vancouver and London were causing a stir online, B.C.’s Bonnie Henry, called for an end to the prohibition on hard drugs and proposed that the province provide options for people to buy opioids without a prescription. This was met with a swift response from the left-wing NDP government, which pushed back in disagreement—a signal that the tides on drug policy may be turning.

In the end, however, Henry may have only been the canary in the coal mine. A few days after her plan was released, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre shared a post online suggesting that secret documents had been uncovered indicating that the federal Liberal government, at that time supported by the NDP, had a “national decriminalization” plan of their own. Though the details were scarce, it shows just how popular some of these harm reduction policies have become.

This despite legitimate criticism that surrounds much of the research and data used to affirm them; in February, The Hub published an article calling the “landmark study” from the B.C. Centre for Disease Control “junk science.” The study attempted to showcase that access to “safe supply” decreased mortality rates among drug users; however, it seems researchers didn’t properly control for other factors, like typical dosages of OAT (opioid agonist therapy) given to safe supply drug users versus the control group.

Data from a 2022 study out of Peterborough, Ontario is met with similar issues; it touted that participants in their safe supply program saw a 79 percent reduction in overdoses and an 86 percent reduction in unregulated fentanyl use. But there’s one major flaw: the majority of the data referenced in the study was based on second-round interviews, of which only 16 out of 41 participants took part. The gap in data relating to the remaining 25 participants provides significant uncertainty around the program’s true success date.

Denial in the face of criticism

The backlash to Canada’s worsening drug crisis is predictably growing. The experimental programs launched at the hands of progressive policymakers have allowed what was once considered relatively localized examples of disorder to unfold into a widespread complete and utter catastrophe.

The reaction from the Left to this, however, is telling. In regard to the Telegraph article, for instance, instead of focusing on the significant issues covered, they deflected attention to its less pressing details. A chorus of angry voices on X accused the journalists of promoting “addiction porn.” Others, including a local reporter, proclaimed that they simply “parachuted in” without sufficient knowledge about the complexities contributing to the city’s crisis, while some went on a “fact-checking” campaign focused on what they considered key inaccuracies — mainly, that the crisis was already spiralling before the decriminalization trial had begun, and that there are some U.S. cities who hold a higher record of overdose deaths per capita.

This reaction was perhaps the perfect demonstration of the toxic culture that’s festered behind the scenes, one which continues to drive many of these policies today. Progressives must stubbornly maintain the illusion that the overall harm reduction model is the right approach to drug policy, or else admit that the entire scheme may have been a failure.

Of course, none of that can change what is painfully evident with our own eyes: the overarching drug policies that have been implemented over the past two decades have failed. They’ve failed those suffering from addiction, and — most critically — they’ve failed society. Today, it seems impossible to keep going in this direction. But that it took us this long, and that we allowed so much damage before we’ve started to change course, will leave a mark on our country for decades to come.