Interest rates are on the decline.

The Bank of Canada has cut its main policy rate three times in a row—and is widely expected to do so again next week, perhaps even by an outsized half-point cut.

You might naturally be tempted to think the pain of high rates will be over soon.

Not so fast.

The greatest effect from recently high interest rates has still not arrived, and the monetary drag will remain with us for some time yet, even if rates drop quickly soon.

Though there will no doubt be much celebration as rates return to normal. And the government is sure to keep taking credit. But in the months and years ahead, you should keep some much-needed context in mind.

First, accelerating rate reductions are themselves a sign of concern that the economy is weakening. If growth slows, then future inflation pressures ease and rates can come down faster.

Second, and more to the point, just because the Bank is lowering interest rates doesn’t mean it has taken its foot off the brake.

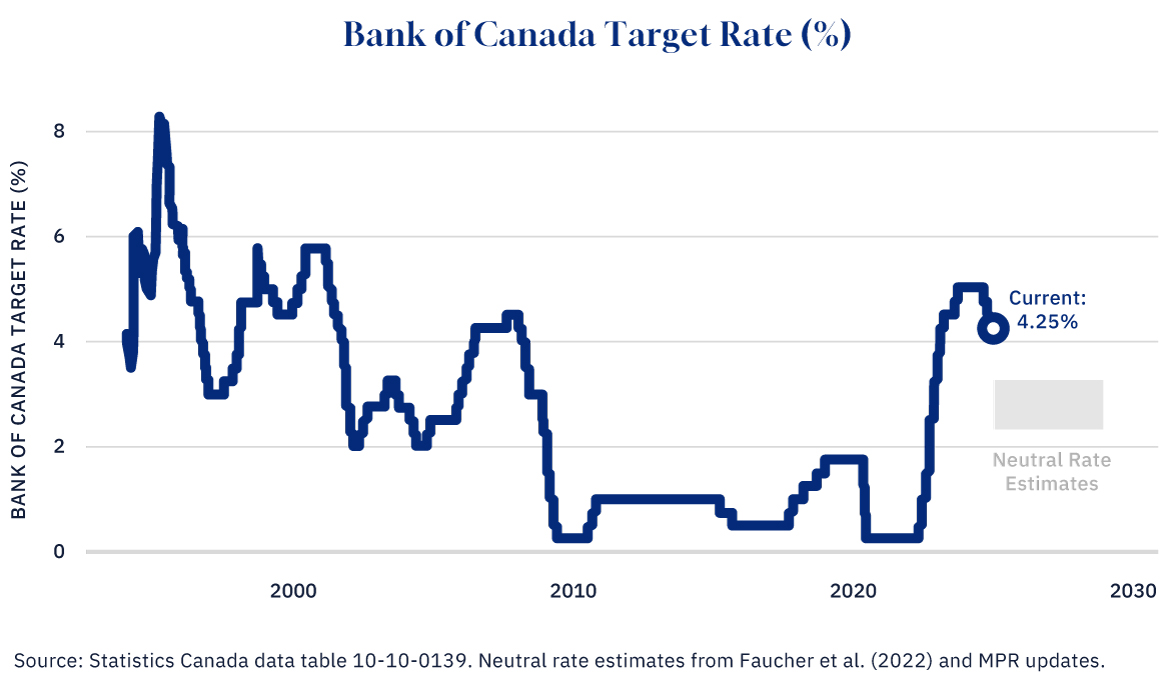

Though lower than before, the main Bank of Canada interest rate remains above the so-called “neutral rate” that would prevail in a normal, sustainable level of economic activity with inflation right on target.

We don’t know precisely where that is, but somewhere between 2.25 and 3.25 percent is the current best guess. Any rate above that tends to slow the economy. Any below, the reverse.

According to some recent projections, we might not see rates fall below three percent until the middle of next year and it might not be until the end of next year before we’re comfortably at the neutral rate.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

So we’re certainly easing off the brake, but we’re breaking nonetheless.

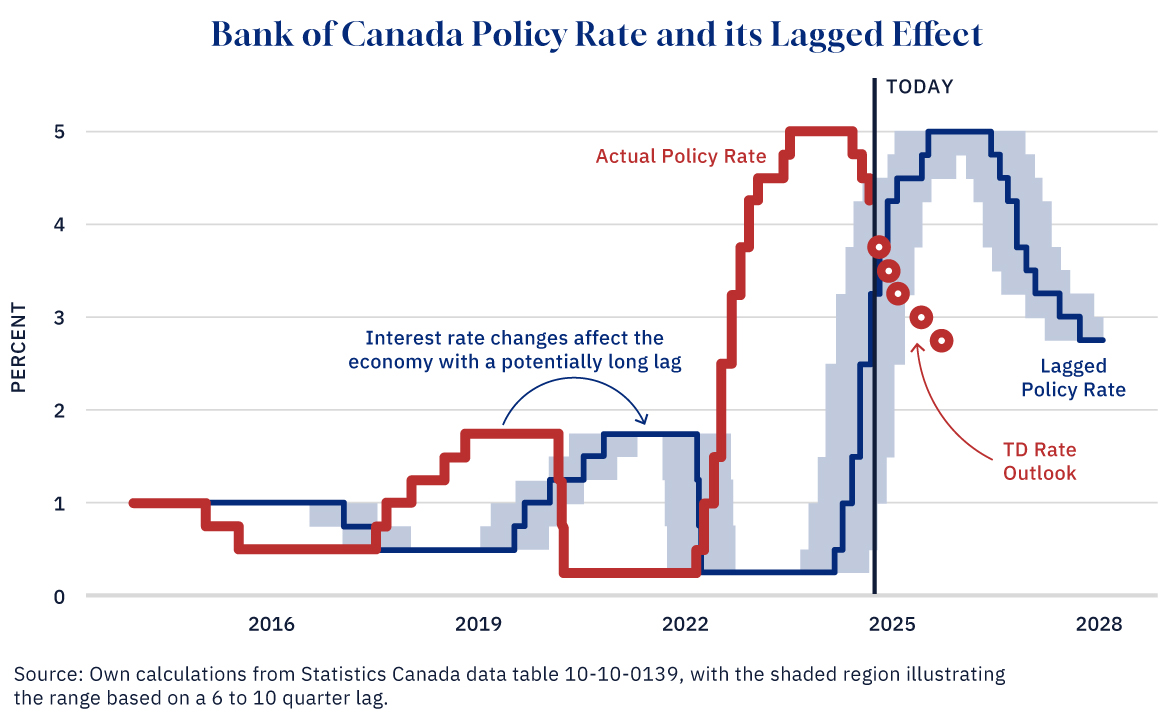

The third reason to temper enthusiasm is the most important of all: interest rates work slowly. Very slowly.

In fact, what matters most for the economy today is not where rates are, but where they were.

It takes time to adjust business investment decisions, household savings decisions, consumer spending decisions, and more. Some of this is obvious. High rates make borrowing more costly, which means items we tend to borrow to purchase tend to see lower demand. Home renovations, new vehicle purchases, and so on, are highly affected.

But interest rates affect us in many other ways beyond. Increasing interest payments on debt leaves fewer dollars available to spend on other items. This is especially important for mortgage holders, which will take a long time to work its way through the system. High rates, after all, lower the amount of mortgage principal that households are repaying, which means much lower consumption spending further into the future.

High rates also increase the incentive to save rather than spend. Indeed, the size of personal term deposits has grown considerably since rates started to rise. From about $800 billion in March 2022 to nearly $1.1 trillion today in July 2024, which might be locked in for some time. Personal chequing deposits, meanwhile, have declined over this period.

Finally, though this is by no means an exhaustive list, high rates redistribute wealth across individuals in a way that matters for the overall economy. High-income elderly individuals are the greatest beneficiaries while younger families just starting out face mounting burdens. This matters since the consumption of older households is lower and might be less sensitive to income changes than that of younger households. (As an aside, successive policy choices by the government to benefit seniors at the expense of others are particularly perverse in this environment.)

In short: the economic shadow cast by the Bank’s previous high rates is long and will for some time to come. Their effect is already baked in.

For how long? It is tough to know for sure, and depends on the circumstances. There’s good research suggesting that the full effect of rate changes takes one to two years to arrive. So since the Bank increased rates to five percent on July 12, 2023, the full effect might not be felt until at least January 2025 or later.

The Bank maintained that high rate until April 10, 2024. Fast forward 18 months from there and we’re in mid-October 2025. If the lag is in the longer range of 24 months, then the effects last until April 2026—over a year and a half from now. Canada’s high level of consumer and mortgage debt could mean lags even longer than this are not out of the question.

So if rates decline as the latest TD Economics’ outlook anticipates (used just for illustration), then the effect of monetary policy on the overall economy might not be back to “normal” until 2028.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The bottom line is that the path forward will not be as smooth as many hope. The economic pain from high interest rates will linger far beyond today’s early signs of relief. While one can certainly welcome news of falling rates, the influence of past higher rates will continue to weigh on economic activity for quite a while yet.

Politically, this reality will challenge incumbent governments as voters may not feel the benefits in time for upcoming elections (in B.C., Saskatchewan, and New Brunswick now, and the federal government potentially soon). We should also be on guard against any claims of victory by governments. The fact that monetary policy has “long and variable lags” (as economists are fond of saying) means Canada’s economic road ahead remains uncertain.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story indicated Manitoba in the midst of an election when it is New Brunswick that is heading to the polls. The error has been corrected.