Bloc Quebecois Leader Yves-Francois Blanchet threatened last week to push for an early federal election over his party’s demands that the government hike old age security payments (OAS) for seniors between the ages of 65 and 74 by 10 percent.

Setting aside the fate of this particular Parliament, Blanchet’s policy proposal has divided economists and policy experts from the general public. On the one hand, economists argue that the elderly in Canada are already quite well off and an additional cash transfer to them is just another item contributing to the federal deficit.

Indeed, the Parliamentary Budget Office has already chimed in that the proposed increase would cost $16 billion over the next five years—potentially aggravating both the deficit and the debt. On the other hand, a recent poll finds that three-quarters of Canadians support to some extent raising the benefit to those aged 65 to 74.

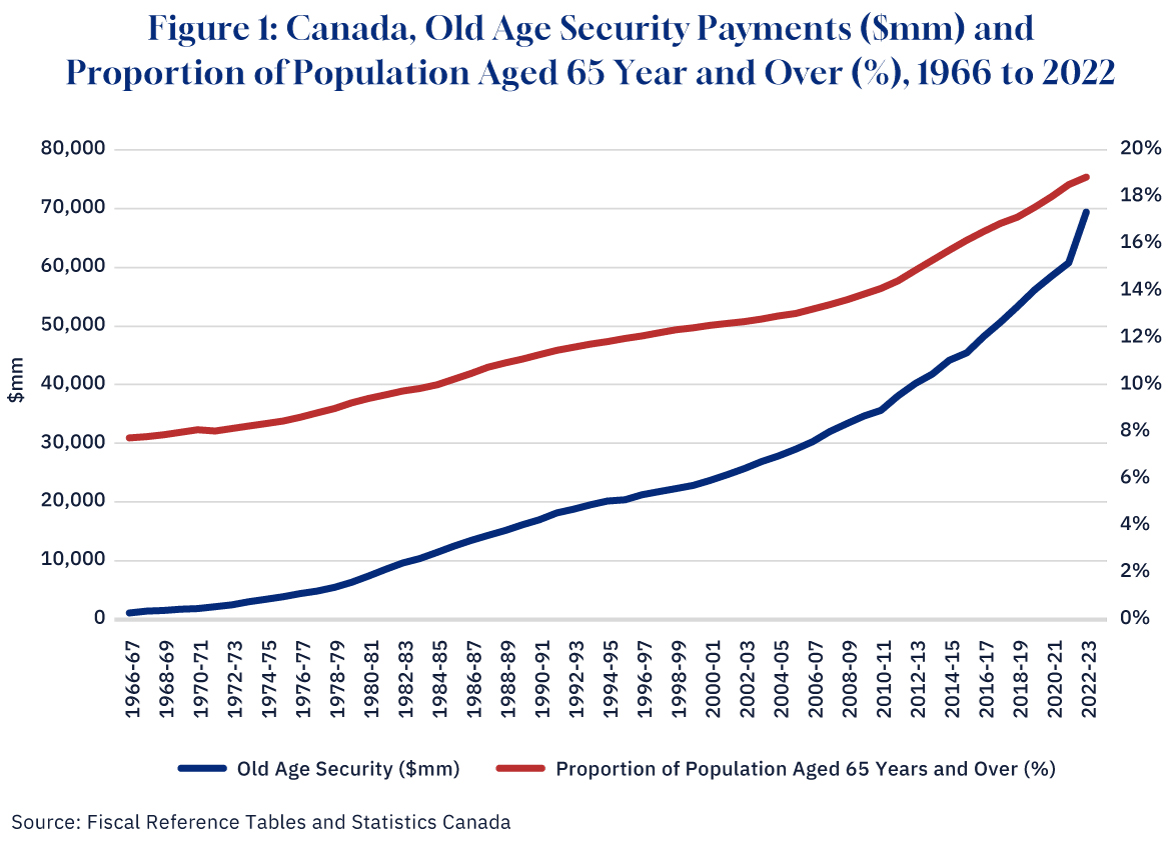

To understand why economists and the public differ can be illustrated with several simple charts. Figure 1 plots the proportion of Canada’s population aged 65 years and over from 1966 to 2022 alongside total OAS payments over that same time period.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

From $1 billion in 1966, OAS grew to $69.4 billion by 2022. As a share of federal spending, it has grown from 10 percent in 1966 to 15 percent by the eve of the pandemic and has only declined to 14 percent because of the overall increase in federal spending post-pandemic.

Economists and policy experts maintain that as the population ages and the proportion over age 65 increases, expenses for OAS will take up an ever-larger share of federal spending. The proportion of the population aged 65 years and over is currently about 18 percent and is expected to reach 23 percent by 2040.

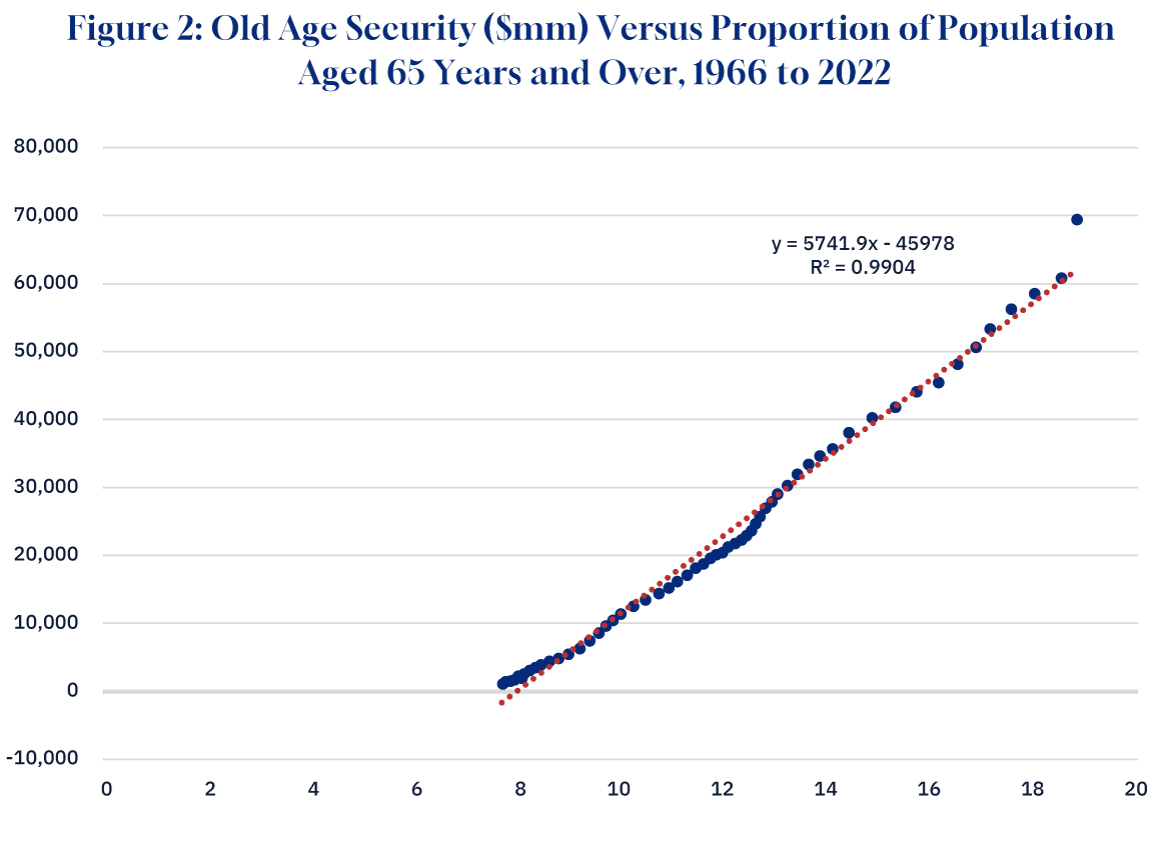

There is a pretty strong linear relationship between total payments and the proportion aged 65 years and over (notwithstanding the outlier bump for 2022) as Figure 2 illustrates. Using this relationship, if the proportion of seniors hits 23 percent, by 2040 the amount spent on OAS could easily be $86 billion.

However, this does not consider the proposed additional 10 percent increase for the payout to seniors in the age 65 to 74 category which combined with the 2022 increase, means that by 2040 spending will definitely be much higher than this linear extrapolation.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Is this sustainable? If spending rises faster than the resource base, then there is a sustainability issue. The ultimate resource base is of course an economy’s GDP, and the evidence here suggests that OAS has never been sustainable and that it has become less sustainable over time. Over the entire 1975 to 2022 period, nominal GDP in Canada has grown at an annual average rate of 6.2 percent while the corresponding annual average growth rate for total OAS payments has been 6.4 percent.

If one examines just the 21st century (2000 to 2022), then nominal GDP has been growing at 4.7 percent and OAS payments at 4.8 percent. If one just looks at the most recent period from 2012 to 2022, nominal GDP has been growing at 4.4 percent annually and OAS has grown 5.7 percent. OAS payments have been growing faster than the economy. Moreover, over time, the growth rate of the economy has been declining, making sustainability a more pressing issue.

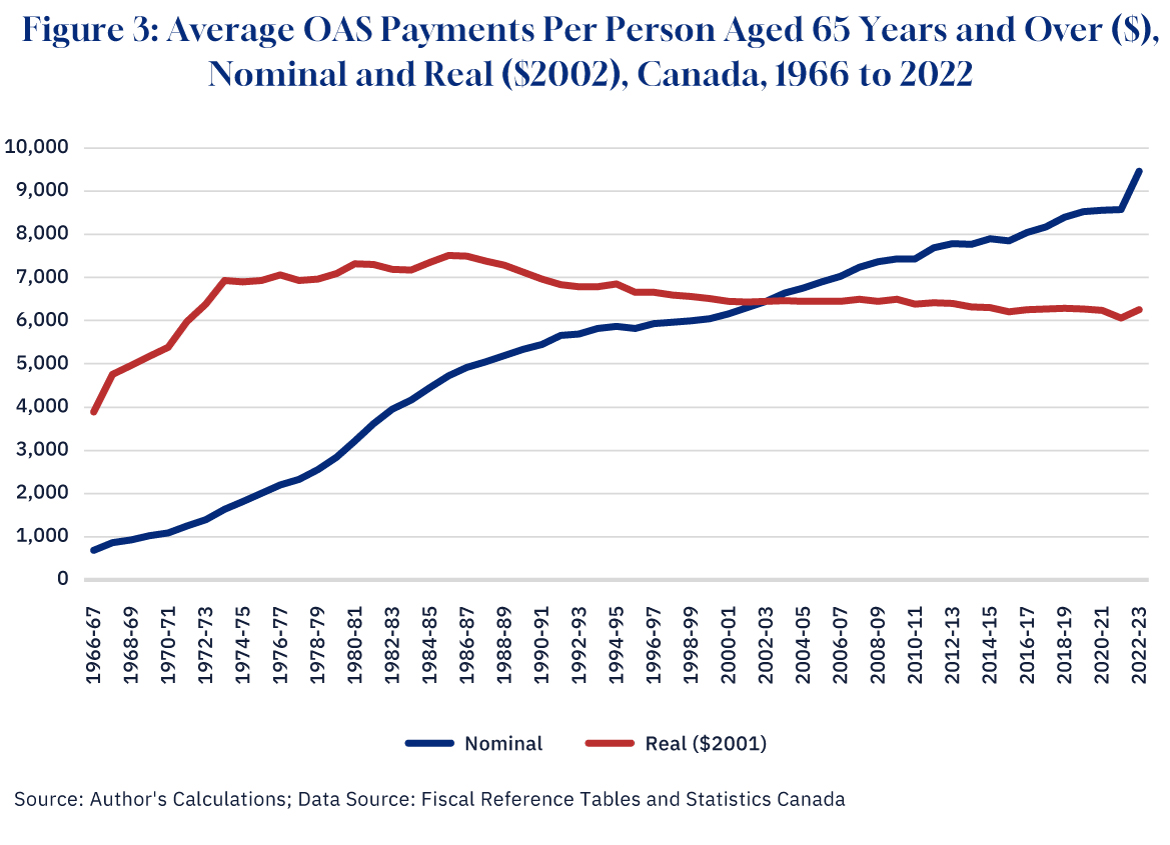

Yet, the general public is immune to this type of argument because it is preoccupied with the all-consuming issue of the cost of living. Figure 3 takes the number of Canadians aged 65 years and over (of whom approximately 96 percent receive OAS) and divides them into total OAS payments to get the average nominal payment per senior. It then also deflates this by the All-Items CPI ($2002) to get the real average OAS payment per senior.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The results illustrate quite clearly why so many Canadians feel that OAS should increase. While the nominal amount has shown a steady increase, after inflation, it appears to have been in decline since the late 1980s. Between 1966 and 2022, the average annual nominal total OAS payment per senior rose from $681 to $9,467. In inflation-adjusted dollars ($2002), the same period saw an increase from $3,892 to $6,261. In $2002, the average OAS payment per senior peaked at $7,507 in 1985 and by 2022—even with the 10 percent bump for those aged 75 and over—was at $6,261 for a decline of nearly 17 percent.

Is there a solution? Given the history of past political scuffles over OAS, the solution will be difficult. How can one increase the OAS further and make it sustainable at the same time? This would involve yet more policy choices. The OAS is currently a universal basic income for those aged 65 and over but as a senior’s income rises above a threshold, there is a reduction or clawback.

For example, in 2023, if income exceeded the threshold amount of $86,912, the OAS pension would be reduced. Specifically, if in 2023 your income was $96,000, then the repayment was 15 percent of the difference between $96,000 and $86,912 requiring a clawback of $1,363.29. In 2024, the minimum income recovery threshold will rise to $90,997 but even so, for those aged 65 to 74, there will continue to be OAS paid out up to a maximum income of $148,451, and for those aged 75 years and over the maximum is $154,196.

As economists are always saying, there is no such thing as a free lunch. If one truly wants a more generous OAS to help lower-income individuals cope with the rising cost of living while at the same time making a better effort at fiscal sustainability for OAS, then something has to give. Perhaps, the payouts to higher incomes need to be reduced meaning the clawback rate needs to be increased or the minimum threshold at which the clawback starts needs to be reduced.

By how much? Well, that is a question for the government of the day, but such changes are fraught with political difficulties given the past history of trying to make OAS more sustainable.

When the Mulroney government in the 1980s moved to limit inflation protection for OAS payments, there were major protests by seniors. The government retreated in the face of 63-year-old Solange Denis and her famous “It’s Goodbye Charlie Brown” statement.

In 2012, the Harper government put in motion a plan to raise the eligibility for OAS from 65 years of age to 67 starting in 2023 with a full transition by 2029. At the time, this change would have affected anyone born after 1958 and was expected to save $10 billion annually once fully in place. However, there was criticism of this plan and it was scrapped by the incoming Trudeau government early in its first mandate.

In the end, when it comes to political expediency or good economic choices, good economic choices always seem to end up sacrificed on the altar of political expediency.