It seemed that U.S. President Donald Trump had made good on his threats to impose tariffs on Saturday, signing an executive order that would impose levies of 25 percent on all imports from Canada and Mexico, except for Canadian energy which would face a tariff of 10 percent. The order included a provision to trigger even higher tariffs if the targets of the order respond with tariffs of their own. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau then quickly responded by announcing a package of retaliatory tariffs. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum also vowed to retaliate. Following last-minute negotiations, however, both Canada and Mexico were able to secure a 30-day delay from the American tariffs.

Clearly, the situation is fluid. While a temporary pause is better than nothing, the threat remains. If the full extent of Trump’s tariffs are eventually implemented, there is a real risk that these actions could spark a trade war the likes of which have not been seen since the Great Depression. As an economist who has studied the macroeconomic consequences of protectionist trade policies, this possibility certainly has me worried.

As I set out below, the key takeaway is that a trade war would be painful for all involved, but more painful for Canada than the U.S. Canada’s GDP losses with broader retaliation could be as large as 1.62 percent. For context, Canadian GDP fell by 5.2 percent (about three times more) during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. But it’s important to keep in mind that our economy bounced back quickly the following year, in 2022. If the tariffs were to remain in place for several years, the cumulative losses could be significantly larger than the losses from the pandemic.

When Trump threatened to terminate NAFTA during his first administration, I developed a computer model to study how this would affect the economies of Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. The model incorporates a detailed depiction of the North American supply chain, frictions that prevent firms from easily switching from domestic to foreign suppliers in the short run, and other features that play important roles in determining how the effects of trade reforms play out over time. My article in the Canadian Journal of Economics contains more details for interested readers. When the details of Trump’s order and the Canadian response were published, I hurried to use the model to simulate what would happen.

Lesson 1: The longer this goes on, the worse it will get for Canada and Mexico.

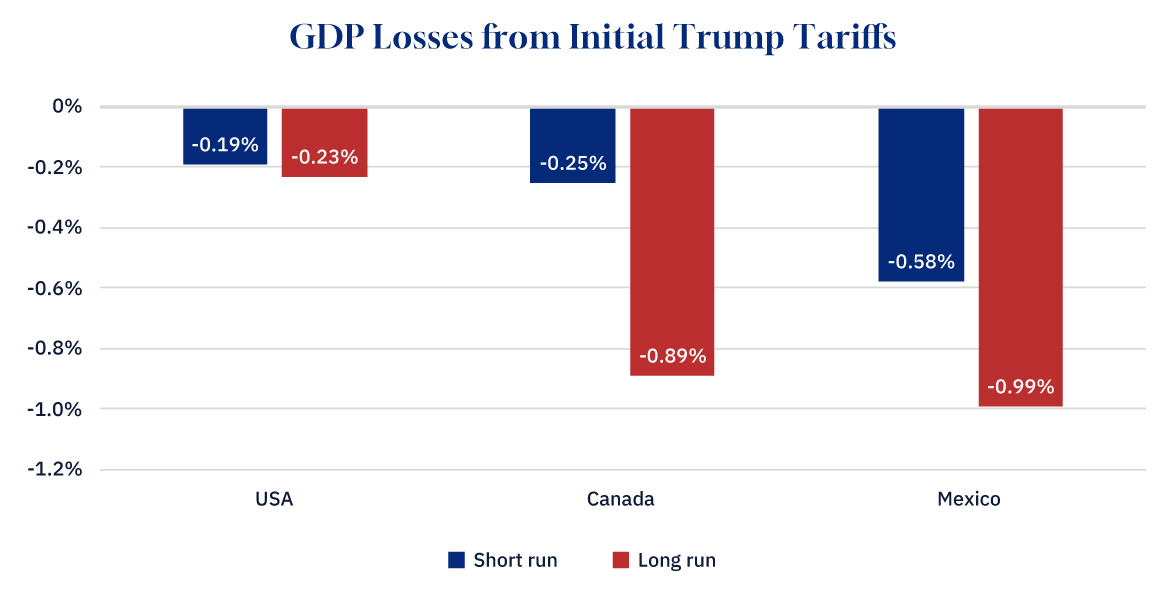

I first modeled the effects of Trump’s new tariffs on their own without any retaliation by Canada or Mexico. In the short term, this would reduce U.S. GDP by 0.2 percent, Canada’s by 0.3 percent, and Mexico’s by 0.6 percent. In the long term, U.S. GDP would not fall much further, whereas Canadian GDP would fall to 0.9 percent below its pre-trade-war level, and Mexico’s would drop 1.0 percent below. In other words, the long-run effects would be about five times larger for Canada and Mexico than for the U.S.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Lesson 2: Retaliation will hurt us much more than the U.S.

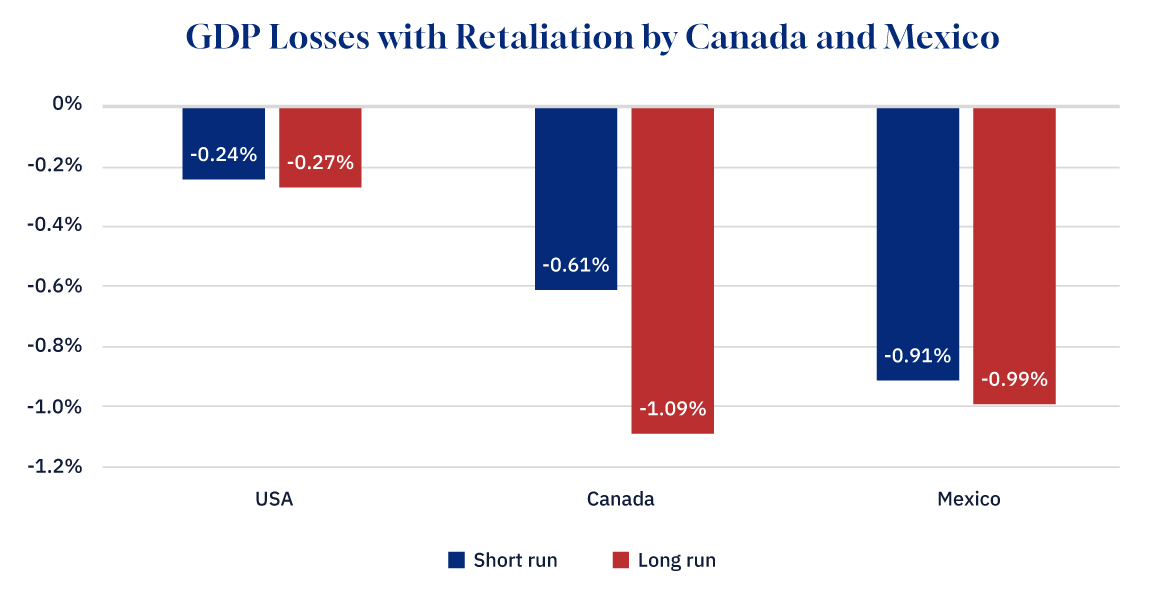

Next, I added in the retaliatory tariffs announced by Trudeau. Unlike Trump’s tariffs, which will hit all Canadian and Mexican products, Canada’s planned retaliation will hit consumer goods, but not the intermediate inputs imported by Canadian producers. The former account for about one-third of total Canadian imports from the U.S. As Mexico’s retaliation plan had not yet been announced, I assumed that it would mirror Canada’s if their new negotiation period is unsuccessful and tariffs are implemented after the 30-day delay. Unfortunately, retaliation will only hurt the U.S. slightly, while it will hurt the Canadian and Mexican economies substantially. Moreover, the pain will come more quickly than if there is no retaliation, especially for Canada, where the initial drop in GDP will be more than twice as large.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Lesson 3: Broader retaliation could make the U.S. feel more pain, but it would come at a steep cost.

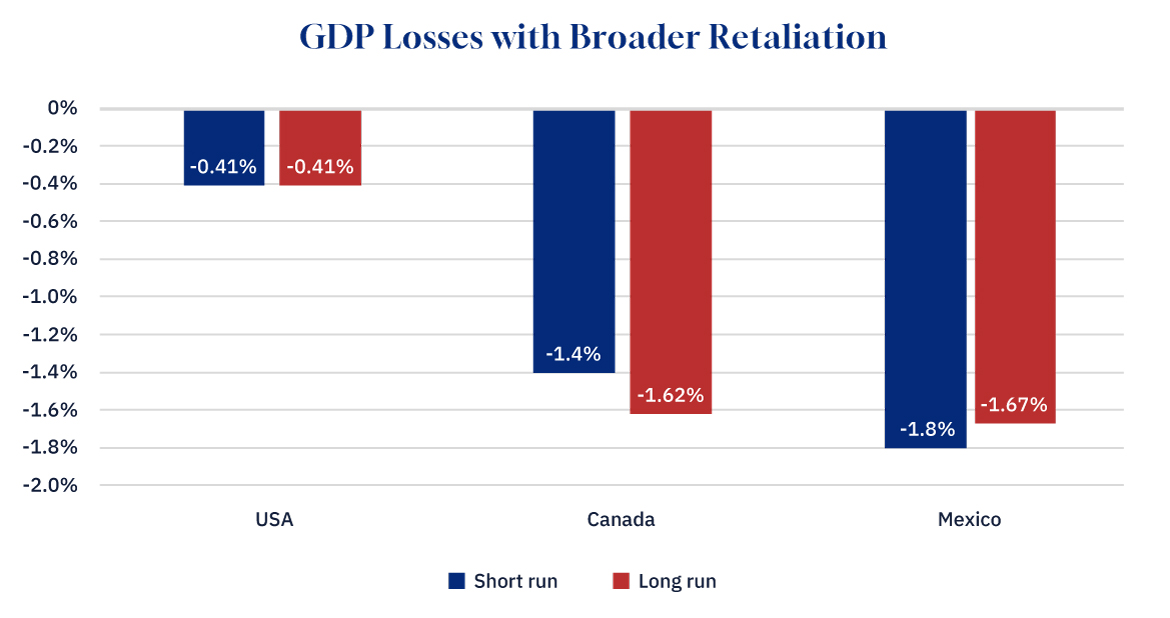

What if, instead of focusing only on consumer goods, Canada and Mexico retaliated by putting “dollar for dollar” tariffs on all U.S. products, including intermediate inputs? This would inflict more pain on the U.S. economy, to be sure, but it would also inflict much more pain on Canada and Mexico. In all three countries, the economic losses in this scenario would roughly double relative to the baseline retaliation scenario above.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Lesson 4: Escalation will be substantially more painful—including for the U.S.

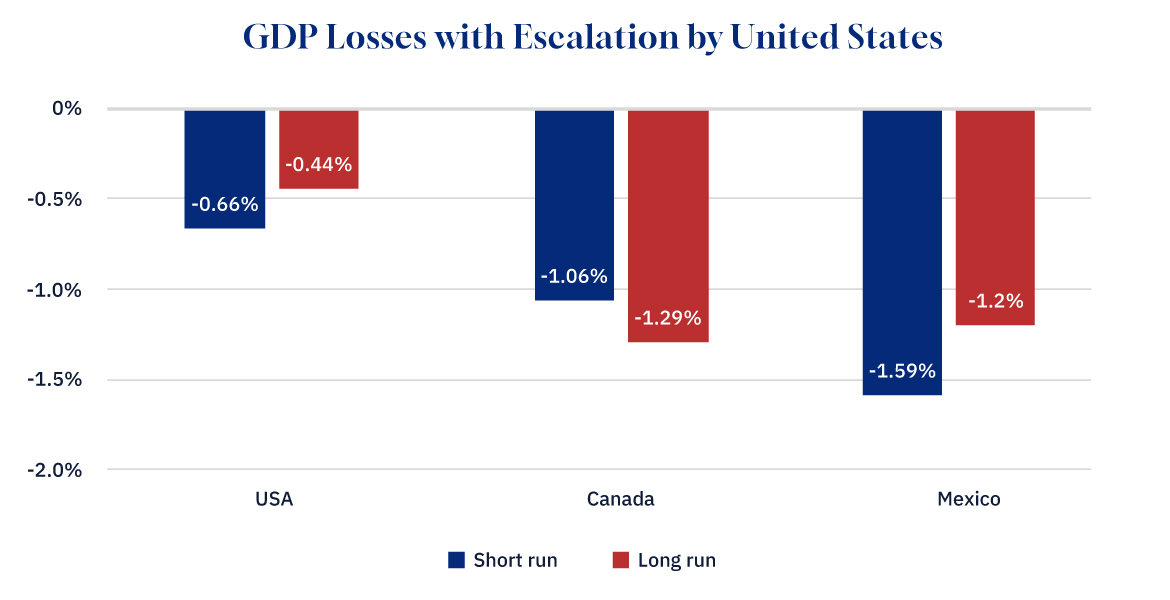

Finally, I modeled what could happen if U.S. tariffs do in fact rise further in response to retaliation by Canada and Mexico. Absent a clear picture of what this escalation might look like, I assumed that U.S. tariffs double, to 20 percent on energy and 50 percent on all other products. This escalation would hurt Canada and Mexico significantly, bringing the short-run GDP losses to 1.06 percent and 1.6 percent, respectively, and the long-run losses to 1.3 and 1.2 percent. However, it would also hurt the U.S. substantially more than the initial retaliation by Canada and Mexico. In the short run, U.S. short-run losses would triple, rising to 0.7 percent, and the long-run losses would almost double.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

It’s worth mentioning that the data used to calibrate the model are a slightly out of date so the numbers themselves should be taken with a grain of salt. But the relative magnitudes—the effects on Canada and Mexico versus the U.S.—can be relied upon, and they reflect an uncomfortable asymmetry. The reality is that trade with the U.S. is simply far more important for Canada and Mexico than vice versa.

Take Canada for instance. Exports make up about a third of our GDP, and about three-quarters of these exports (about a quarter of our GDP) go to the U.S. The U.S., on the other hand, relies much less on trade, with only about 10 percent of its GDP going to exports. Moreover, while Canada is America’s most important export destination, its exports are far more diversified than ours; less than 20 percent of U.S. exports (about 2 percent of its GDP) go to Canada. This means that the U.S. economy has much more capacity to absorb the shock of these tariffs—and the retaliatory responses to them—than ours.

This asymmetry indicates that Canada and Mexico are likely to gain little economic leverage over the U.S. by retaliating, and what leverage they do gain will be very hard won. If there’s one silver lining in my findings, it’s that further tariff hikes will be relatively more costly than the initial round of tariffs for the U.S., which may reduce the likelihood of a vicious cycle of escalation.