By any objective measure, the Ford government’s performance on homebuilding has been somewhere between mediocre and abysmal. Surprisingly for a right-of-centre government, the causes of this poor performance are a combination of skyrocketing housing construction taxes coupled with overly burdensome regulations. Ontario’s failure to create an environment conducive to homebuilding becomes particularly clear when placed in contrast with Alberta.

The fairest way to judge a politician’s performance is against the goals they set. At a Ford Fest event in September 2023, the premier helpfully laid out his housing vision, stating “We’re going to offer a 1,600-square-foot home, with a basement that’s finished that you can rent out or have family there. You’re going to have a backyard with a fence. You’re going to have a paved driveway—under $500,000.” Ford would go on to add that the government would help facilitate the building of “thousands and thousands” of starter homes.

This vision never came to fruition. There are few places in Ontario where you’ll find single-family homes, let alone 1,600-square-foot ones with finished basements and paved driveways priced under $500,000. The latest Canadian Real Estate Association data shows that average single-family home prices in southern Ontario range from $1.45 million in Oakville and $1.3 million in Mississauga to $594,000 in Kingston and $570,000 in Tillsonburg.

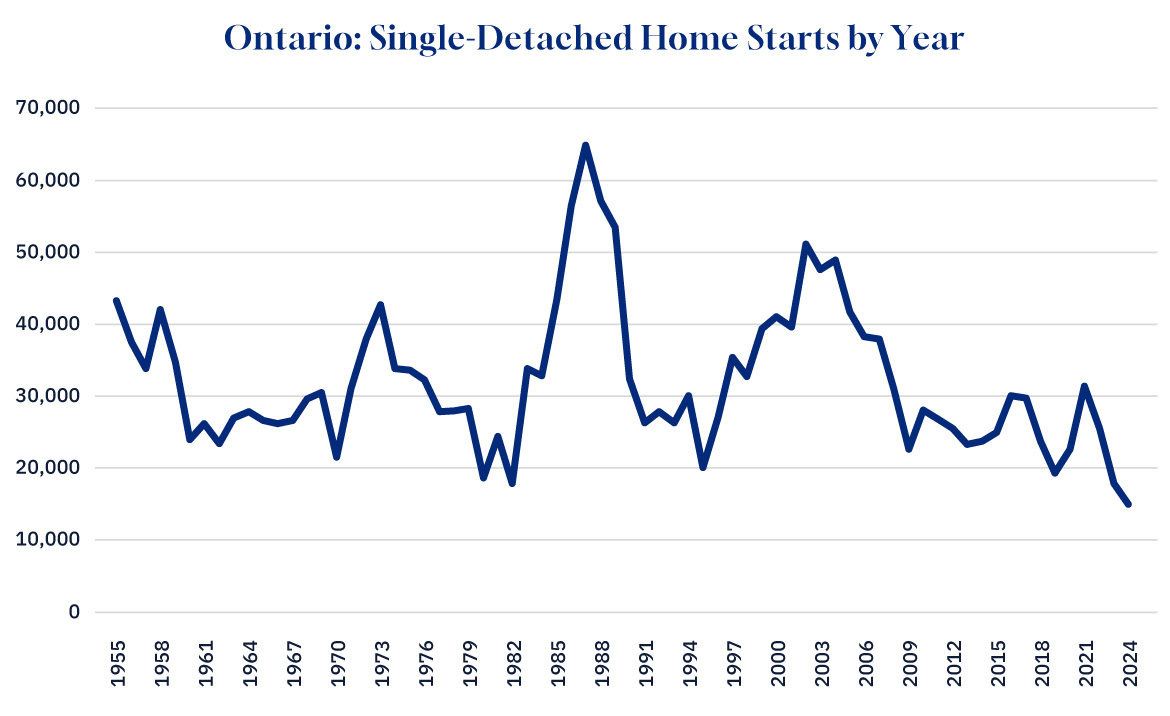

These family-sized homes are expensive because they are both in demand and exceptionally rare. In 2024, there were only 15,000 single-detached home starts across the province, the lowest figure in the province’s recorded history. In comparison, single-detached home starts were 43,000 in 1953, the year the records began. Construction of these types of homes has fallen considerably over the last twenty years, a phenomenon that has only gotten worse under this government.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

If we expand Ford’s definition of family-sized homes to include semi-detached and townhouse units, the picture only looks marginally better. Last year, Ontario had its fifth-worst year ever, and worst year since 1982, for single-detached, semi-detached, and row housing unit starts.

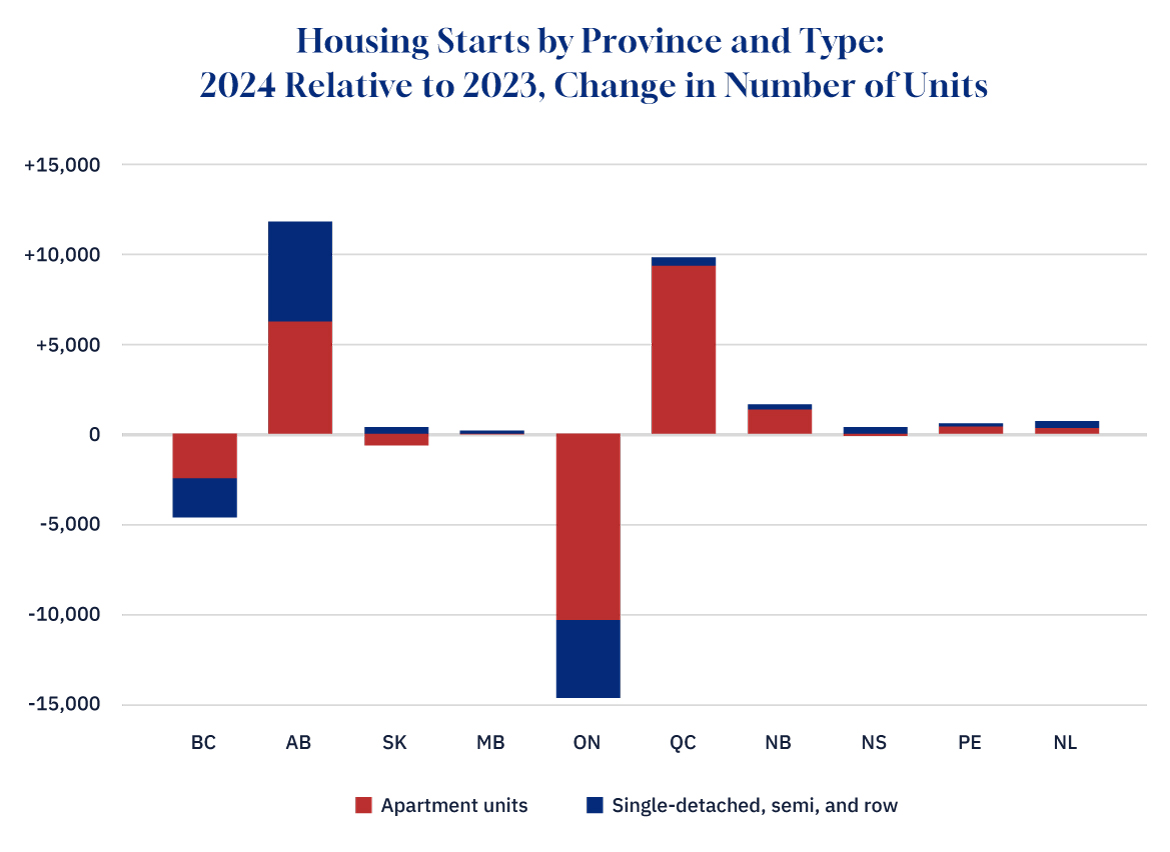

The Ford government has acknowledged the drop in housing starts, with Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy citing higher interest rates as a contributing factor. While interest rates do impact the homebuilding sector, other provinces have been able to increase housing starts in the face of higher rates. In 2024, housing starts increased in seven of 10 Canadian provinces, and while starts dropped by nearly 15,000 units in Ontario, they rose by nearly 20,000 units in the rest of Canada.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The contrast between Alberta and Ontario is stark, particularly since both provinces have Conservative governments. This raises the obvious question of “What is Alberta getting right that Ontario is getting wrong?”

A Canadian Home Builders’ Association report from 2023 can shed light on this question. One major difference between the two provinces is taxes. Municipal charges, including development charges, on low-rise development in Calgary were $42,800 a home in 2022, and in Edmonton, they were $29,353. Contrast this with the City of Toronto, where they were $189,325 a home, and Markham’s $162,348. A 2024 update of cities in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) showed that across 15 GTA municipalities, these charges rose an average of 34 percent between 2022 and 2024, adding an extra $42,000 in municipal charges alone. These tax increases make building homes cost-prohibitive, which slows housing construction.

While it was Ontario municipalities, not the provincial government, that raised these taxes, the municipalities did so under the provincial Development Charges Act. The province had attempted to slow down the increase in development charges with their 2022 More Homes Built Faster Act (Bill 23), they repealed those provisions under the 2024 Cutting Red Tape to Build More Homes Act (Bill 185), so municipalities were free to hike development charges.

We should not overlook the role that provincial taxes play in the two provinces. Unlike Ontario, Alberta has no sales tax on new homes, and while Ontario does have a partial tax rebate, the maximum value of the rebate is achieved when a home is priced at $400,000, as the conditions for the rebate are not inflation-adjusted, and have not had any type of adjustment in over a decade. Ontario also has high land-transfer taxes; a $1 million home in Ontario would pay $16,475 in these taxes, compared to just $740 in Alberta. And if that Ontario home is in Toronto, an additional municipal land transfer tax applies.

Another vital difference between the two provinces is in the length of time it takes to get a development project approved. In Calgary and Edmonton, based on 2022 data, it took an average of five and seven months respectively. In Ontario, average timelines ranged between 10 months in London to 23 months in Markham and 32 in Toronto. A 2024 update of cities in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) did show an improvement, with the 15 GTA municipalities now taking an average of 20.3 months, down from 22.7, but still well off Calgary’s five-month timeline. And Alberta continues to innovate, with Edmonton being the first municipality in Canada to provide automated development permit reviews.

Finally, we cannot overlook land use regulations. Unlike his counterparts in other provinces, Ford has been particularly hostile to legalizing fourplexes and other reforms that would give landowners more options on the types of housing they could build as of right. And when it comes to opening more land to development, such as expansion of urban growth boundaries, the issue has become even more politicized due to the Greenbelt scandal. If cities lack both options to build up, and options to build out, then building simply will not happen.

Ontario’s housing crisis is not going away, and these problems from high development charges to poorly designed regulations, can be fixed. I am cautiously optimistic that a provincial election will cause all of the parties to bring ideas forward, and adopt those proposed by experts, to end our housing construction malaise.