The data science lab at Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital has developed more than 50 Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools for use in the health-care system.

Some, like an automated scheduler for nurses’ shifts, are relatively mundane. Others, like CHARTWatch, have saved lives.

Once an hour, CHARTWatch considers 150 to 170 data points for a given patient—such as their age, heart rate, and blood pressure—to predict the risk that they will die or need to go to the intensive-care unit in the next 48 hours. The software doesn’t require a human to actively monitor it. And if the high-risk threshold is breached, it automatically alerts the patient’s medical team.

Thanks to CHARTWatch, “We’ve been able to document a 26 percent reduction in unexpected mortality,” said Dr. Muhammad Mamdani, who runs the data science lab at St. Michael’s.

The lab is a rarity for a Canadian hospital. Why aren’t there more?

“That’s a good question. I think there should be many more,” Mamdani said.

Advocates of using AI in health care say the tools can improve health outcomes while automating rote tasks so doctors and nurses can spend more time caring for patients.

“The quicker AI is embraced in healthcare, the sooner we can start saving lives, reducing unnecessary strain on our doctors and nurses, and building a system that can work better for everyone,” wrote Louise Pichette, senior manager of health sciences at MaRS Discovery District.

AI applications in health care are still largely in the testing phase but have shown promise so far. There’s evidence that AI can improve the effectiveness of diagnostic imaging—mammograms, for example—by spotting patterns that a human eye alone could miss. AI has beaten humans at detecting skin cancer and breast cancer. It has been used to locate participants for clinical trials for new treatments and then to help manage and accelerate those trials. It’s been suggested that AI could help ease Canada’s shortage of family doctors.

Implementing AI in health care could also save time and money by finding administrative efficiencies—Unity Health’s automated scheduler for nurses’ work shifts, for example, can do in minutes what would otherwise take a human administrator several hours. Already in Canada, AI scribes that take notes on doctors’ behalf are becoming more common as a solution for the reams of paperwork that general practitioners deal with (the president of the Canadian Medical Association said they spend between 10 and 19 hours a week on administration).

The consulting firm McKinsey and Company estimated that Canadian governments could save $14 billion to $26 billion in the health-care system a year by using AI extensively to reduce administrative burdens.

Nevertheless, there are challenges to implementing AI across the health-care system. The tools can make serious errors and be biased against certain groups. AI software often requires operators to input large amounts of data in order to “train” it, which can create a risk that personal medical data will be breached.

Ultimately, said, John Hirdes, a professor in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo, AI can’t replace the human values that inform decision-making in health care—for example, whether doctors should try to extend a person’s life by a month even if they’re in extreme discomfort.

“We want a health-care system that corresponds to the value preferences of Canadians,” he said. “AI systems can’t replace our value framework.”

Hirdes urges policymakers to view improving patient outcomes as the number one priority when considering how to introduce AI into the health-care system—not saving money.

“If we can reduce unnecessary administrative work, that’s great,” Hirdes said. But “for me, outcomes, [patient] experience, staff experience and equity are the first things we solve. And then cost-effectiveness.”

Governments must move with more urgency

Nevertheless, while the federal public service is forging ahead with its AI strategy, there hasn’t been similar progress at the provincial level to harness the technology to improve health-care delivery—by far the largest public expenditure in Canada at $372 billion for all governments combined last year.

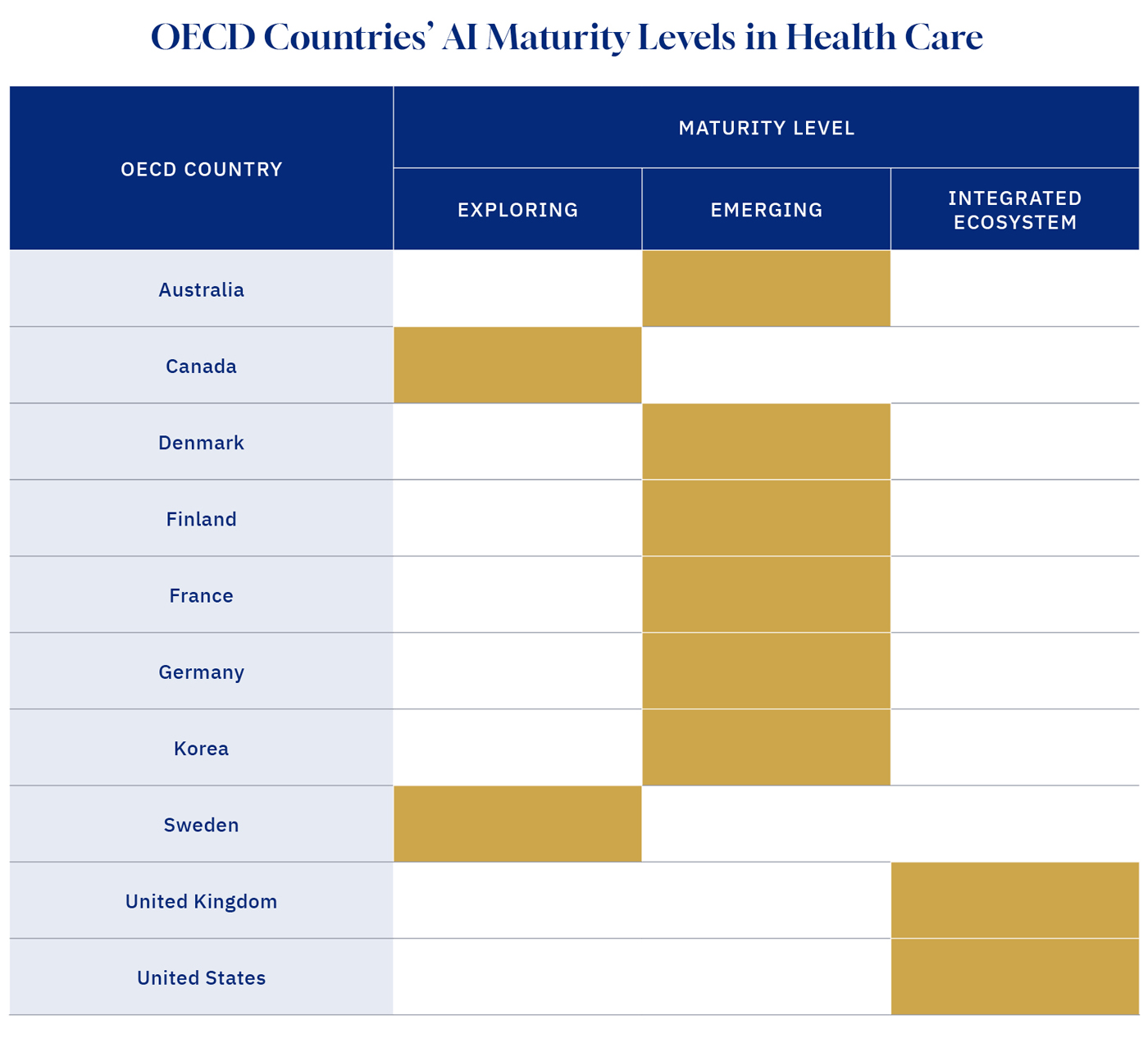

Most of Canada’s peer countries are already ahead of us in reaping those benefits, according to a paper published last year in the journal Health Policy. A team that included three researchers based in Montreal evaluated 10 OECD countries’ health care “AI maturity.” The analysis relegated Canada to the lowest or least mature of three levels, along with Sweden. Only the United States and the United Kingdom occupy the highest tier, known as “Integrated Ecosystem,” and the remaining six countries are in the middle “Emerging” tier.

Source: Health Policy, Feb. 2024; Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

In a 2020 report, the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research’s health-care AI task force lamented how “Canada has lagged behind many peer nations in its pace of uptake of digital healthcare innovations.”

The task force called upon the provinces and federal government to collaborate on a national AI health strategy. “Failure to seize these opportunities will have adverse consequences for the quality and efficiency of our health-care systems, the health of our communities, and the prosperity of the nation,” it warned.

In the absence of clear government leadership on AI in health care, researchers and health-care practitioners who want to harness the technology are having to figure things out for themselves.

“There hasn’t really been any formal collaboration with the government. I’ll be very frank, I don’t know if the government has a good strategy around all of this,” Dr. Mamdani said. “I don’t think they have a good plan around what a comprehensive health AI strategy would look like on the ground.”

Unity Health has partnered with medical technology startups to disseminate its innovations, Dr. Mamdani added, “Because as a hospital it is really difficult for us to spread our technologies to hundreds of other hospitals, because we’re not a business, that’s not what we do.”

He doesn’t think private-sector partnerships are a bad thing. But it would be better for Canada’s health-care sector if governments stepped up and played a role in advancing AI technology. He said Canada needs to decide whether it wants to be an innovator, early adopter, or laggard in this space.

“I think it’s a matter of vision. It’s a matter of resources as well.”

This article was made possible by Google and the generosity of readers like you. Donate today.