On Thursday, March, 20, The Hub’s editor-at-large Sean Speer gave remarks at a National Speakers Bureau showcase event about the upcoming federal election and the threat to Canadian national unity. The following essay is an edited version of his speech.

If your job like mine is commenting on policy and politics, it’s admittedly a bit of a torturous time.

On one hand, we’re living in a target-rich environment. There’s lots to talk about, to say the least. It’s not typical for instance for the president of the United States to speak openly about wanting to annex your country.

On the other hand, the whole thing is a bit exhausting. We’re on day 59 of Trump’s presidency. There are still 1,402 left. But who’s counting?

I want to spend the next several minutes though convincing you that our biggest risk isn’t Donald Trump’s talk of making Canada the 51st state. It’s how we respond to his persistent provocations that may actually prove to be a bigger threat. The risk is that if we’re not careful, we can cause fault lines within our own society to open up and create a permanent chasm between Canadians in different parts of the country.

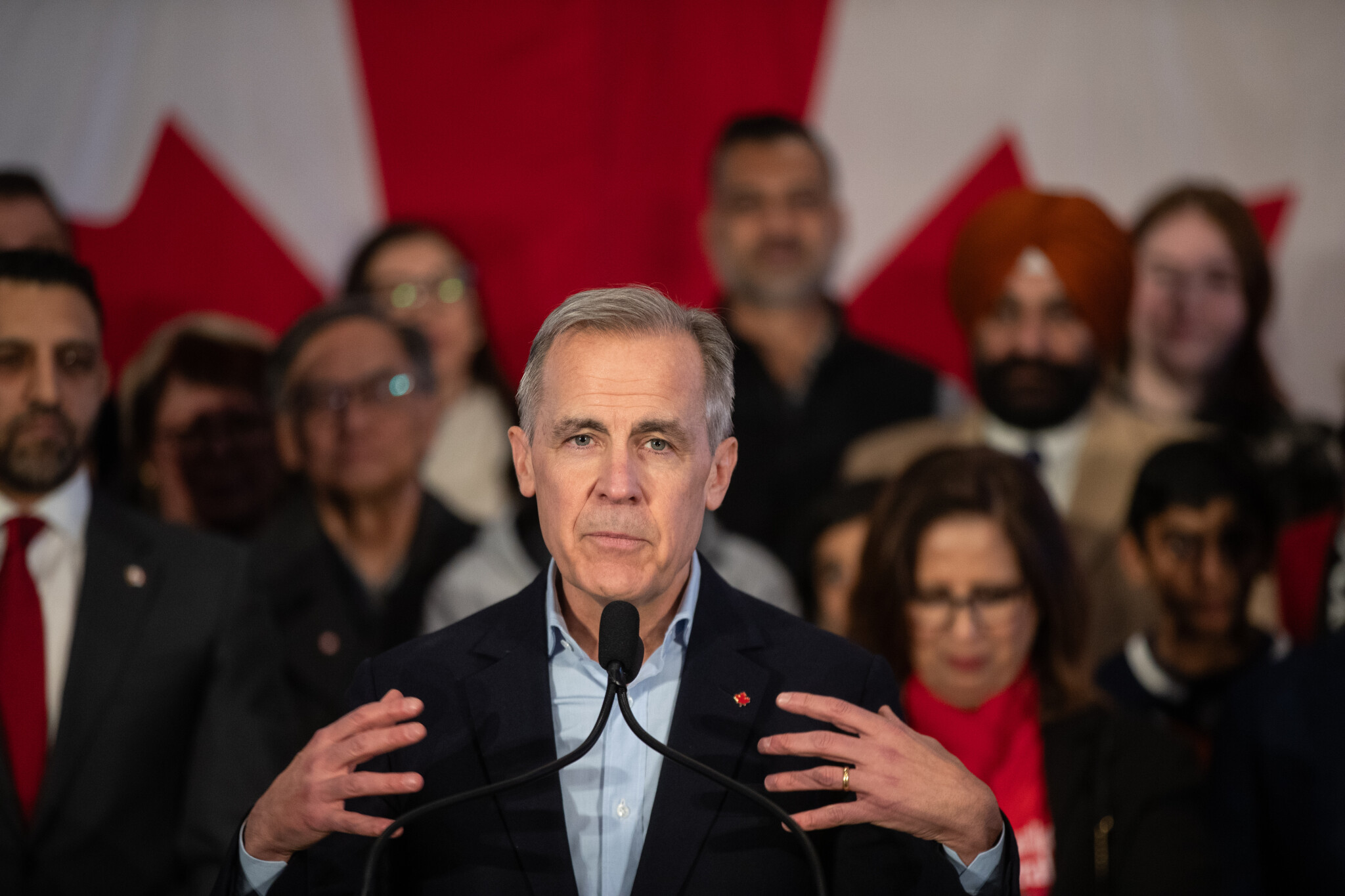

If reports are accurate, Prime Minister Mark Carney will trigger an election on Sunday. It’s bound to be one of the most consequential in our lifetime. Trump will invariably be at the backdrop. But so will national unity.

I worry in particular that the campaign exacerbates regional tensions across the country. One might think of it as a zero-sum political battle between Alberta and Saskatchewan on one hand and the Via Rail corridor of Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto on the other.

By way of background, the former is home to 48 federal parliamentary seats or just over 14 percent of the House of Commons. The latter is a bit bigger: it’s home to 51 seats or slightly more than 15 percent of the House of Commons.

Yet while they’re roughly similar shares of Parliament, their politics couldn’t be more dissimilar. The Conservative Party represents 44 of Alberta’s and Saskatchewan’s 48 seats whereas the Liberals hold 48 of 51 seats in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto.

These numbers are crucial to understanding Canadian politics—particularly as we head into an imminent election campaign.

To put a fine point on it: the Conservatives have nearly 92 percent of the seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan and the Liberals hold about 94 percent of seats in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto.

To put an even finer point on it: these electoral percentages mean that Liberal voters in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto alone essentially have a veto on the voting preferences of Conservatives in Alberta and Saskatchewan.

One way to think about it is for the past three federal elections, Albertans and Saskatchewanians have overwhelmingly gone to the polls and voted to elect Conservative governments, and yet they haven’t gotten what they wanted. Voters elsewhere in the country—particularly those in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto—have canceled out their vote.

One might argue that that’s fair. That’s how elections work. That’s of course true. But these regional dynamics can create powerful political incentives for the different parties as well as strong feelings in the regions that are key to understanding Canadian politics.

The sense of Western alienation that we often hear about is kind of “baked into” our political system. It reflects an arguably justified perception that the region’s contributions to the country are high but its influence is low.

Mark Carney speaks during his Liberal leader campaign launch in Edmonton, on Thursday January 16, 2025. Jason Franson/The Canadian Press.

We shouldn’t underestimate its consequences. Recent polling tells us not only that Western alienation is currently high—perhaps at historic levels—but the share of the population that’s open to becoming the 51st state is by far the highest in the country.

Nearly one in five Albertans for instance say that they’d vote in favour of joining in the United States if a referendum was held today. An even higher share—more than one in four—believes that they’d be better off if they were part of the U.S.

Which brings us to the election campaign. As I said, it’s not going to be a normal campaign—and not just because there’s a good chance that the president of the United States live tweets it.

As candidates are knocking on doors and Canadians are starting to make judgements about how they intend to vote, we’re expecting to be walloped by the latest round of American tariffs.

On April 2, the Trump administration’s tariffs—as much as 25 percent across the economy and 10 percent on energy exports—are set to come into effect.

This is what political scientists would describe as an “exogenous force” and the rest of us might call a “big f-king deal.” It has the potential to influence the election in unexpected yet significant ways.

Particularly, if as it has been speculated, the administration opts to proceed with the 25 percent across-the-board tariffs but exempts oil and gas exports.

Canada’s oil and gas exports to the United States are by far our biggest. They’re worth about $140 billion per year. To put that in perspective: automotive exports are $60 billion annually.

The significance of oil and gas exports is precisely why the Americans would exempt them from tariffs. It’s a sign of how valuable they are to the U.S. economy.

Yet therein lies the political risk for Canada.

If oil and gas exports are exempted from tariffs, there will be calls on federal political leaders to impose an export tax—which is basically a tax on Canadian energy companies that export oil and gas to the United States.

The purpose would be to raise prices on American companies and consumers as leverage in the ongoing trade dispute. Ontario Premier Doug Ford has called it a “trump card” in negotiations with the Trump administration.

There’s no doubt that an export tax on oil and gas exports would hurt America’s economy. But it would also be an explosive issue—a flashpoint—in the campaign that would split the major parties along regional lines.

The political incentives for Carney and the Liberals would presumably tilt in favour of supporting such a measure. Not only would it demonstrate their willingness to take a hard line against the unpopular Trump administration, but given they only have limited support in Alberta and Saskatchewan, the political costs would ostensibly be low.