In geopolitics, the strong are rarely threatened, much less attacked. As we weigh the options for the future of our country in the midst of a federal election, Canada finds itself a target from our neighbour to the south because we are economically weak. The good news is that our weakness is largely self-inflicted and is reversible.

An OECD report lays it bare: among 38 advanced economies, Canada is forecast to come in dead last in long-term GDP per capita growth.

Canada’s energy CEO’s sounded the alarm bell in an open letter that pinpointed regulation as an impediment to investment and job creation. This should be a core issue that each leader vying for Canada’s top job should have an answer for. The financial services sector, which employs 10 times more Canadians than oil and gas, requires political attention too.

Canada’s financial sector has been historically resilient in the face of economic shocks, including the Great Recession of 2008-09. Our regulatory regime protects consumers, ensures firm-level solvency and systemic financial stability. These are important public benefits.

Trade-offs abound, however. Higher capital requirements and stricter supervisory practices deter international investment and impede innovation. From an affordability perspective, every regulated financial entity builds the costs of its compliance program into the prices it charges consumers. More regulation, higher costs.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

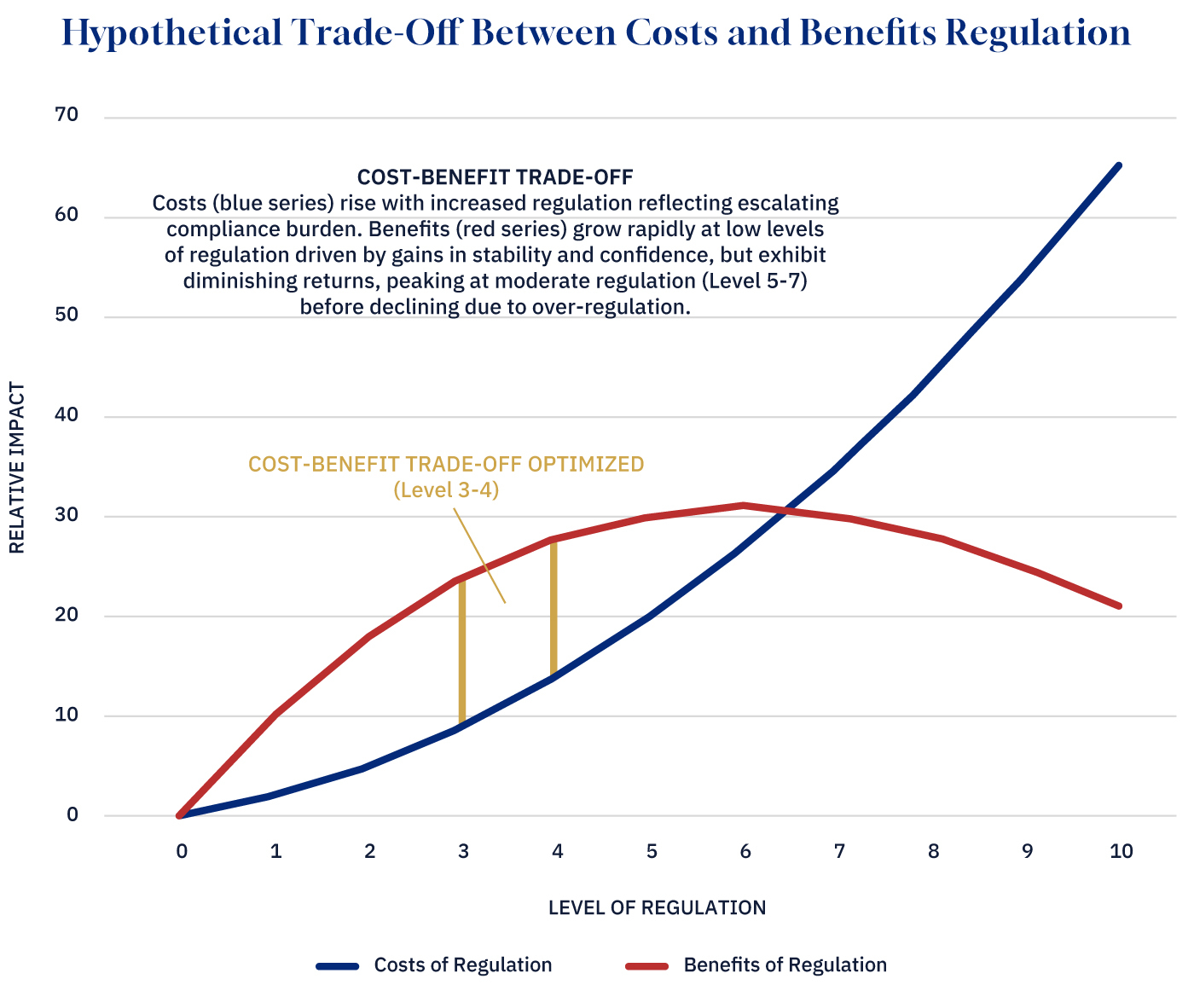

Let’s not quibble about whether regulation is needed. Of course it is. However, the fact that regulation is limited implies that too much regulation or the wrong kind of regulation can be harmful. The challenge is striking a balance between the benefits and costs.

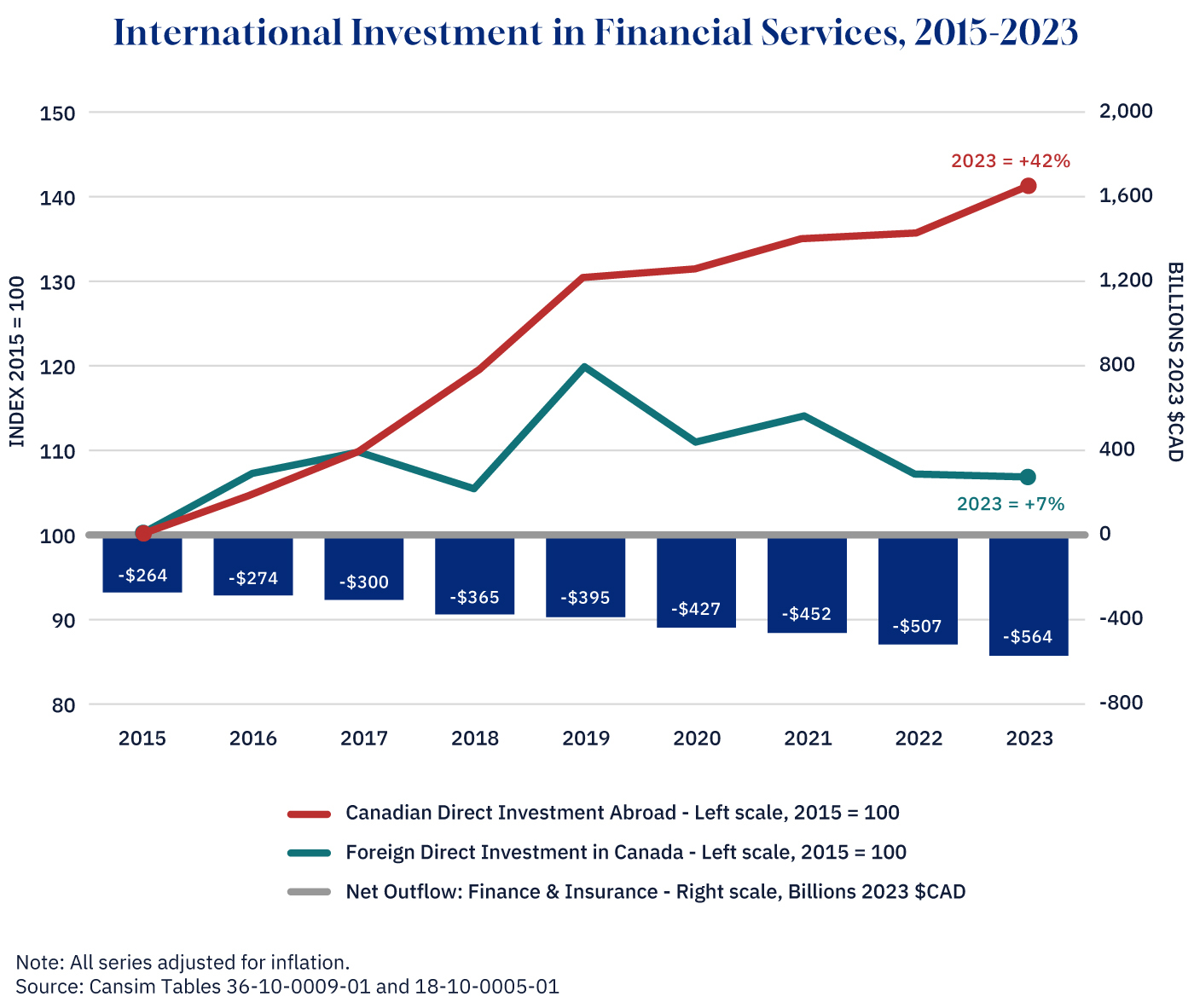

Here the data is flashing red. Canadian direct investment abroad jumped 42 percent from 2015 to 2023, signalling attractive financial services opportunities outside of Canada. Meanwhile, foreign direct investment in Canada crawled up just 7 percent. The net outflow doubled from $264 billion to $564 billion in just eight years. This gap signals Canada is losing its edge, bleeding jobs and capital overseas.

Unpacking the causes of Canada’s deteriorating financial sector competitiveness is challenging, but it stands to reason that the regulatory regime has a bearing on the relative attractiveness of Canada.

Recent research from the C.D. Howe Institute finds that Canada’s regulatory burden has grown significantly over the past decade, increasing compliance costs and reducing competitiveness. The report uses textual analysis to conclude that there is an imbalance between solvency and stability, on the one hand, and efficiency, competition, and innovation, on the other.

How should we think about the balance between stability and competitiveness? As regulation increases, the associated costs rise, reflecting the escalating compliance burden placed on firms. The benefits of regulation also rise at low and moderate levels of regulation, but eventually plateau, reflecting diminishing returns, before declining due to over-regulation. Moderate levels of regulation maximize the trade-off between benefits and costs.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

That’s the theory, but how do we measure the actual costs? We can cluster the costs of regulation into three categories: direct (administrative), indirect (compliance), and induced (including opportunity) costs. Let’s ignore the latter.

Quantifying the direct costs of regulation is straightforward. Most, though not all, financial regulators assess the entities they regulate, charging a fee to fund their operations. By my count, there are at least 18 financial regulators at the provincial and federal levels. Adding up their operating budgets, we land on $1.42 billion in administrative costs. This is the smallest part of the regulatory burden.

The indirect costs of regulation, which include the compliance costs of regulated entities, are much steeper and are more difficult to measure. They encompass in-house compliance staff (including IT, audit, reporting) and the third parties (consultants, technologists, lawyers) retained to support compliance programs.

A pioneering, though now dated, study out of the University of Washington found that for every $1 spent by a regulator on regulatory or supervisory activities, $20 is spent by the regulated private sector entities in compliance. Using a range of methodologies, other studies have tried to quantify the cost of regulatory burden. Adjusting the findings of these studies to generate a comparable multiplier, some studies come in lower ($5 in compliance costs for every $1 spent by regulators), but multiple studies come in closer to the 20:1 multiplier (see here and here, for example).

In a country like Canada, which has multi-level regulation, often with duplicative (or more) reporting requirements, it is reasonable to suppose that Canada comes in at the higher end of the range.

This 20:1 multiplier is sobering. Instead of the cost of financial regulation coming in at $1.42 billion, we have compliance costs adding $28.4 billion to the price tag, pulling the total closer to $30 billion. Putting this estimate in context, the typical Canadian household would spend $1,850 each year to ensure the safety and soundness of the financial institutions that service their banking, insurance, pension plan, and investment fund needs. That’s a steep price to pay when pocketbooks are pinched.

Canadians have long benefited from a robust regulatory framework that protects consumers and prevents dangerous risk-taking on the part of financial institutions. However, regulators cannot ignore economic considerations, such as efficiency or the cost-of-living crisis, when creating their expectations around risk management.

As we confront Canada’s economic vulnerability and seek to elect a new government, we must insist on efficient financial regulation that attracts capital and encourages innovation. Absent that, Canada will continue to underperform economically and serve as a takeover target for political expansionists.