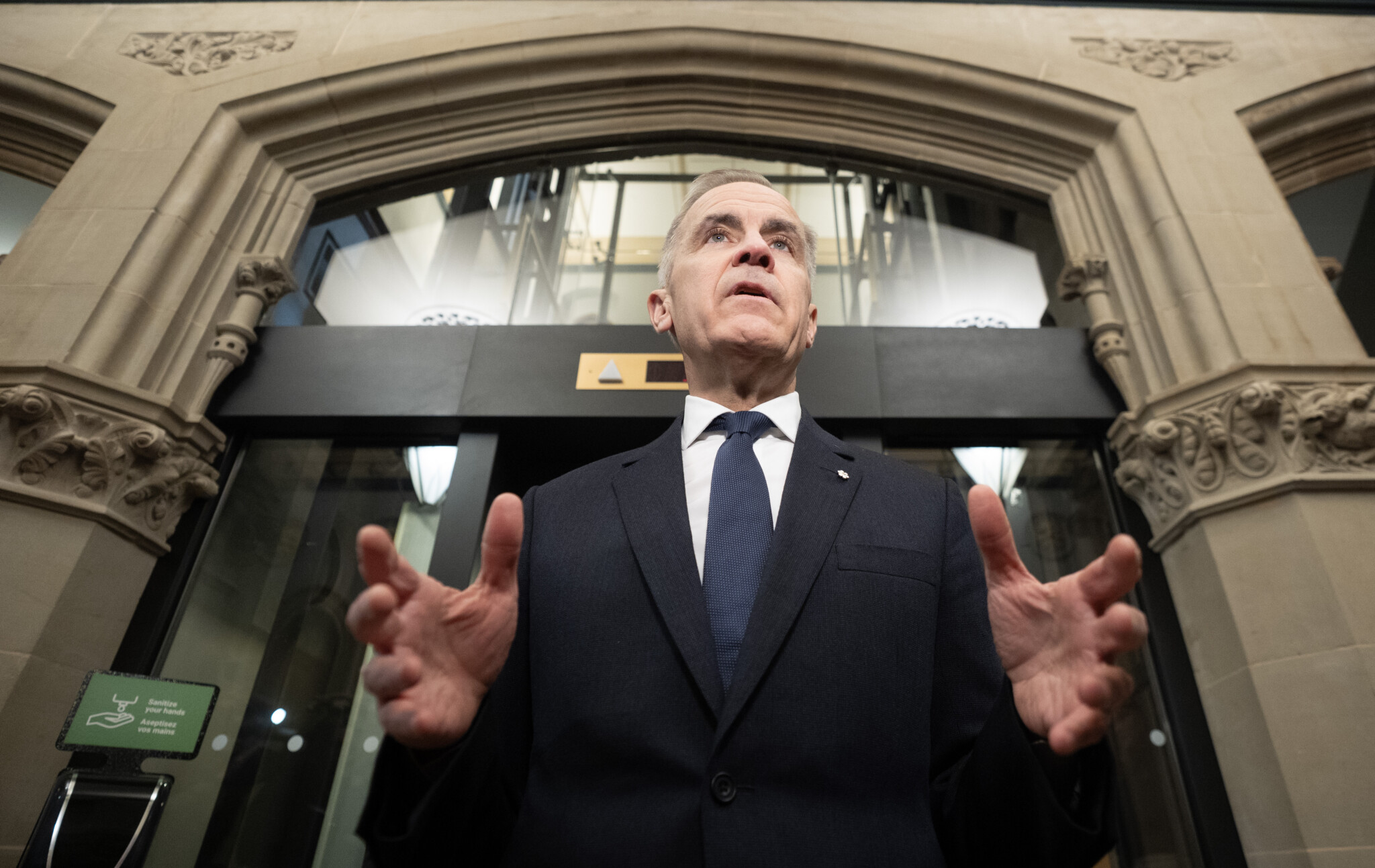

Just how much should Liberal leader Mark Carney be allowed to leave the campaign trail for the prime ministerial podium to make announcements on behalf of the nation, but which also benefit the Liberals at the polls?

The Hub’s managing editor Harrison Lowman reached out to Carleton University associate professor Philippe Lagassé, a parliamentary and Westminster expert, to discuss the caretaker convention and whether it’s written in stone or what it allows for. An edited transcript is included below.

HARRISON LOWMAN: What is the caretaker convention?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: It’s a series of rules. It’s not one single rule, which is part of the reason that we run into trouble with it. We call it a convention, but it really is a series of different things.

So, on the one hand, part of it deals with whether or not the government is able to use government resources for partisan purposes and things of that nature that’s disallowed or that’s clarified in the convention.

But then there’s another piece to this, which is that when a government either loses the confidence of the House of Commons or when Parliament is dissolved, which is what we have today, there is no legislature to hold it to account. And therefore what we demand of the government is what’s called “the principle of restraint.” So it’s not that they can’t exercise legal authority. It’s not that they don’t have legal authority. It’s not that they cease to be the government. They are always the government. What we ask of them, though, is that they restrain themselves.

HARRISON LOWMAN: How does the convention define restraint?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: The idea is you shouldn’t do anything that is not routine or that couldn’t be easily reversed by a future government.

The basic principle is that if you can avoid doing things, you should probably avoid doing them.

But there are a number of caveats that are put in place in the guidelines that are important for us to appreciate. The first one is the government retains the ability to act in matters that it deems urgent and in the public interest.

It can also act in ways that may be irreversible, but should do so only when consulting with opposition parties. So if there’s something really urgent that you need to act on and you need to do, and the other opposition parties are on board, you can get away with it.

But the key thing is really this notion of the public interest. The guidelines have been updated a number of times with each election, and in this most recent update, we’ve seen language introduced about the importance of acting globally. And it’s not odd for us to see that this coincides with the tariff threat from the president in the United States.

HARRISON LOWMAN: The other day, the Globe and Mail ran an editorial that called Carney’s “expansive use of the prime minister’s mantle in this campaign” “problematic.” Do you think it’s problematic?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: It’s a difficult one for me, to be honest, because these are fairly unique circumstances. It’s always been a bit frustrating for somebody who works on this stuff. I kind of point to the fact that this convention exists, but it also has these caveats for these exceptional circumstances.

Part of the problem is that it’s very much in the eye of the beholder. Is it in the public interest for the prime minister to deal with the president of the United States and to have a call with him? I mean, you can make that case.

Should he be calling the secretary general of NATO? Well, if you take an expansive view, I suppose you could fit it in within that. We also have the Ontario precedent, where, just a couple months ago, the premier basically said, “Look, I’m premier and I’m going to be premier all throughout this election.”

HARRISON LOWMAN: Including in Washington, D.C.

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: Yeah. The circumstances have kind of demonstrated the fragility. It really does reinforce to me, these rules and this restraint ultimately depend on the judgement of the prime minister.

We then depend on the electorate to punish a prime minister who acts inappropriately. The problem is this seems to be helping the prime minister with the electorate.

This is highlighting the limits of this rule. And others have commented, I think of Ian Brodie, former chief staff to Prime Minister Harper, who makes the argument that this whole thing is a mirage. It’s not real.

HARRISON LOWMAN: I think for Ford, and Carney too, it’s kind of like a steroid for their campaign. You get to appear in front of the podium with the beautifully carved maple leaf and look like a prime minister or premier.

I want to point out this disconnect. You wrote recently, “The PM and cabinet should not use government resources to advance partisan agendas or help them win re-election.”

And yet, I was listening to the Curse of Politics the other day—a podcast of political strategists who were talking about caretaker—and they said, “We’ve been saying Carney should be PM as many days of the week as he can be. Those are better campaign days for him [than making announcements].”

It’s clearly helping him win this election, or improving his chances, and he seems to know it’s helping him win. No?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: Yeah. I think the key point to make here, and it’s one that I find really frustrating, is it’s the media who insists that there’s somehow a difference between Carney as the Liberal leader and Carney as the prime minister. The reality is he’s always prime minister.

HARRISON LOWMAN: So he’s not taking off the candidate cape and putting on the other prime minister cape?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: He’s not changing capes. He’s like Superman. It’s always a uniform that he’s got underneath, right? And he gets into the phone booth, and then he switches it up, but it’s always there, right?

He isn’t pausing his campaign to become prime minister for a while. He’s always prime minister.

He’s basically using the incumbency advantage to its maximum effect. There’s nothing in the caretaker guidelines that makes this clear distinction between the partisan role of the prime minister and the prime ministerial office, and it’s not one that we recognise outside of elections either.

HARRISON LOWMAN: I think some are frustrated because it’s during an election, where you want things to be fair. You want a level playing field. And there’s obviously a home ice advantage when you’re already the prime minister.

The Globe pointed out Carney has taken up prime ministerial duties on something like 35 percent of the campaign days.

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: I’m not saying it couldn’t evolve, right? We may get to a point where we want the caretaker guidelines to be clearer on this, and we say no when it comes to certain activities. Like we would make a distinction between the prime minister in their official executive capacity and that person as the leader of a political party running for re-election. But the challenge I have is that that’s not what it currently says, and it’s not what our Constitution currently demands. We’re seeing a clash between public expectations and constitutional reality.

HARRISON LOWMAN: Who’s the final arbiter here? Would there ever be an instance where the Privy Council Office would step up to a prime minister and say, “Sorry, prime minister, you can’t be doing that according to X, Y, Z, or does the prime minister have final say in terms of what he or she gets to do in front of that prime ministerial podium during election?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: We don’t know exactly what the conversations are. I would hope that the Clerk of the Privy Council has intervened in some cases and maybe had a word with the prime minister. …Caretaker really is just a creature of the Privy Council Office.

That said, the Privy Council Office isn’t exactly known for its propensity to stand in the way of prime ministers. It’s the prime minister’s department. It’s there to enable the prime minister.

So you may have fearless advice, or at least someone saying, “Look, prime minister, this this kind of off board. You shouldn’t do that.” But at the end of the day, the problem is, the decision ultimately lies with the PM. It’s the PM who decides what they think is appropriate within the confines of the rules.

HARRISON LOWMAN: Why can’t a senior civil servant, a deputy minister, or someone make these announcements, make these moves, and handle things while we leave politicians to go out on the hustings and try and seek our vote? They can play in partisan waters. And we’d have a clean line of separation between those two things. Why does that not happen?

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: Constitutionally, ministers are always responsible. You always have to have a responsible minister to do things. They have both constitutional and legal obligations and accountabilities and responsibilities.

Presumably, in some cases, have, you could have the clerk or the deputies fulfil that function. But that’s just not the Canadian way. We could get there. I suppose, again, it’s not, it’s not outside of the realm of possibility.

But when it came to the call that occurred between the prime minister and President Trump in the aftermath of a lot of what’s been going on. I don’t think it would be wise to place a functionary in front of somebody like President Trump. When you’re dealing with an adversary or an interlocutor who’s looking for weakness, are you going to put somebody in front of them who is not of their standing? If anything, that’s going to fulfil or reinforce their sense that we’re in a vulnerable position.

HARRISON LOWMAN: They’d be called less than “governor.”

PHILIPPE LAGASSÉ: When you’re dealing with a president who gets upset if somebody doesn’t wear a suit in the Oval Office, I don’t know if you want to send them a deputy minister to speak to.

The problem is there are a number of roles where it would be somewhat inappropriate for an official to speak with an elected representative. So that demands that in many cases we have the prime minister or ministers fulfilling that function. And that’s reinforced by the fact that the Constitution and the number of our laws expect them to do that.

This interview has been edited and condensed.