Canadians are heading to the polls on April 28. The economy, cost of living, housing, affordability, and (of course) Trump are top of mind for many.

But one critical issue that has received little, if any, attention despite its importance for the country’s fiscal and economic future: the mandate of the Bank of Canada.

Whoever forms government after this election will get to both appoint the next governor of the bank (governors serve seven-year terms, with the current one ending mid-2027) and, much more importantly, will also decide on the bank’s core mandate when its current one comes due next year.

There are voices calling for change. Some want the bank to move beyond inflation and take on broader objectives—like employment, inequality, or even climate change. This includes not only a current senator, but also some within the government. Others, meanwhile, prefer to keep a clear inflation target, but at an increased target rate to allow higher inflation over time.

Either move would be a mistake.

Inflation targeting is simple and effective

For the past three decades—at least prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and its aftermath—the Bank of Canada has generally done quite well at keeping inflation low and stable. That success was, in part, thanks to a clear and consistent mandate: to keep inflation, as measured by the all-items Consumer Price Index, at two percent.

Of course, the last few years have tested this framework. Between 2021 and 2024, inflation rose sharply—reaching levels not seen in decades. But this was an anomaly, driven in large part by global energy and agricultural cost shocks after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

What matters more is how the bank responded. Its actions were quick and largely effective. Inflation came down rapidly. In fact, only one in five global inflation shocks over the past half-century have been resolved within two years. Canada was one of them.

This was no accident.

Credibility is enormously important

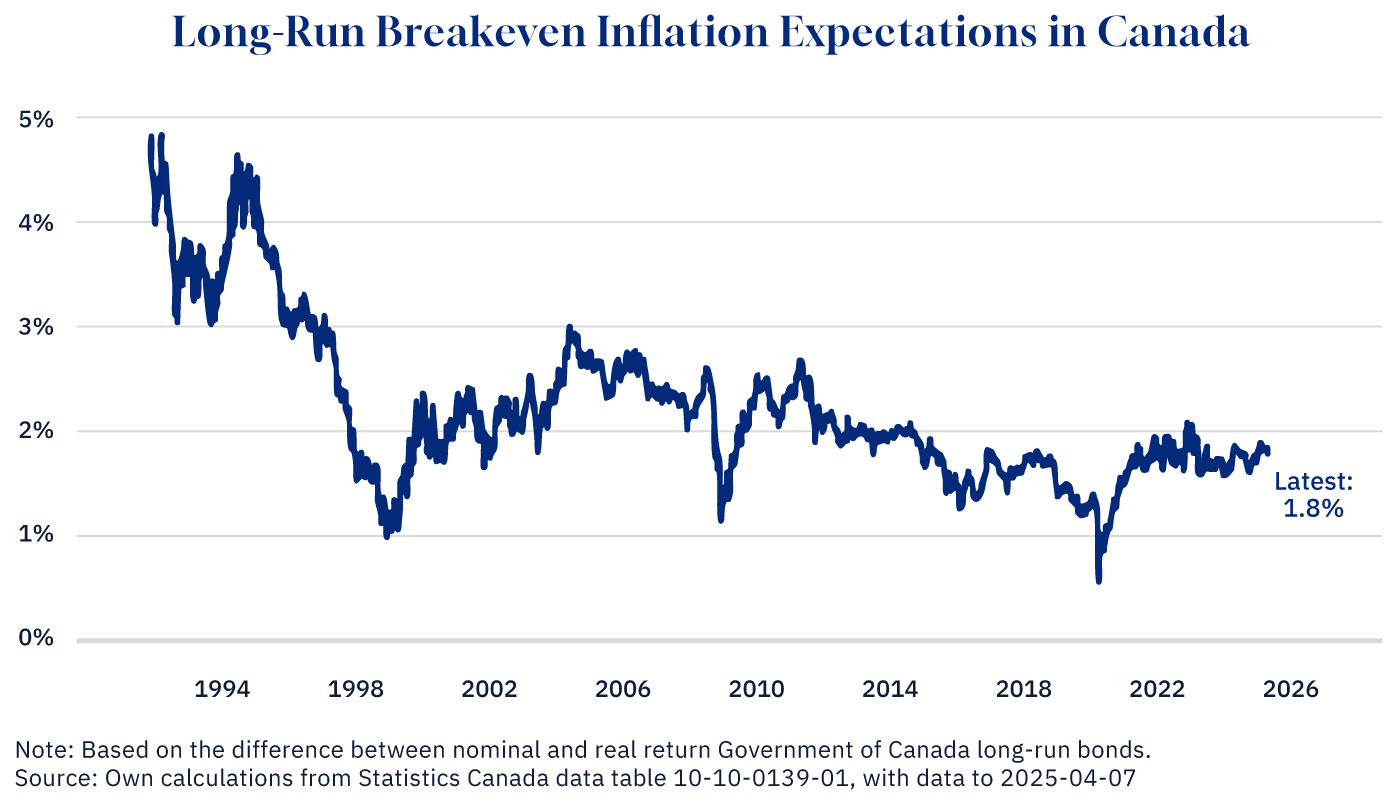

A big reason for the bank’s success was the strength of its credibility. People believed the bank would act—and that belief anchored inflation expectations. We can easily see that in the bond market, where we can infer what investors (putting considerable sums at risk) are implicitly betting on what future inflation will be. As I illustrate below, this rose somewhat following the pandemic, but never much above 2 percent.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

A clear mandate helped make that possible. Without it, the cost of bringing inflation down would have been much higher.

That credibility is therefore a valuable national asset, built up over decades of consistent policy decisions.

To be clear, there’s no objectively perfect inflation target—2 percent isn’t obviously better than 1 or 3 percent. But because we’ve had it for so long, moving away from it now would undermine the credibility of the target itself. This is especially true after the recent inflation shock. Changing the mandate in its wake would introduce uncertainty and could raise questions about whether the bank can stick to its target when times get tough.

When inflation expectations are well-anchored, it becomes easier—and less costly—to maintain low and stable inflation in the first place. That’s something that benefits all Canadians.

While the Bank of Canada may have other responsibilities, such as promoting financial stability, its monetary policy mandate should focus exclusively on inflation.

Inflation is not just a social injustice,To borrow language from Irving Fisher, one of the most influential economists ever, in testimony before a Canadian House of Commons committee in 1923. but a singular goal helps families and businesses plan ahead. Retirement savings, wage negotiations, buying a home, or long-term business investments—all of these depend on predictable inflation. If we introduce ambiguity or move away from the well-established target, that predictability erodes. Planning becomes harder and confidence falls.

Room for improvements

None of this is to say that we should keep the status quo, or that there aren’t sensible changes to be made that could improve the mandate.

The current one, for example, was adopted in 2021 and technically remains focused on inflation. But the last renewal introduced language around employment that has created confusion and genuine risks because reasonable people could read it as a shift toward a broader mandate beyond simply inflation. In my view, that was unfortunate and the result (no doubt) of some within the government pushing for a broader mandate but settling for something less.

The next government could correct that error and return to a clear, unambiguous 2 percent inflation target.

Here’s the core issue: the Bank of Canada has just one broad policy tool—short-term interest rates. To meet multiple goals, like inflation and employment, one tool will not do. And when it comes to employment, it’s not clear that monetary policy is even the best tool. Governments have more effective levers—like tax policy, spending programs, training initiatives, and so on. It’s the fiscal authority that should take the lead there.

Reasonable people could also argue for improvements in the bank’s communications, governance, and transparency. But these operational improvements should not come at the cost of a clear and singular mandate. Clarity of purpose preserves credibility. And credibility is the foundation of effective monetary policy.

As the election nears, Canadians are rightly focused on economic security issues. But let’s not overlook the quiet, technical-sounding issue of the Bank of Canada’s mandate. The next government will, after all, be the one to shape it for many years to come.