In the final week of the campaign, political parties began releasing their fully costed election platforms. And as far as government finances are concerned, the Liberal plan was especially noteworthy.

The platform marks a clear break from the government’s previous approach to fiscal policy and proposes to move Canada onto a less sustainable track.

Of course, former prime minister Trudeau was never one to stress financial discipline. His government frequently strayed from its own commitments around spending, deficits, and debt. But even then, there were nods to long-term sustainability.

It’s worth quoting the government’s own budget documents from last year at length, which highlighted the value of “maintaining Canada’s responsible fiscal anchor”…

… to reduce the federal debt-to-GDP ratio over the medium-term. This metric is key not only for fiscal sustainability, but also to preserve Canada’s AAA credit rating, which helps maintain investors’ confidence and keeps Canada’s borrowing costs as low as possible.Budget 2024, page 22

There’s little to disagree with here. Ensuring that the debt-to-GDP ratio falls over time is a widely accepted indicator of fiscal sustainability. Debt can’t rise indefinitely without consequence—this is not a political statement, but simple arithmetic.

One could take issue with the pace of the government’s previously planned debt reduction, or its ability to stick to its own commitments, but the goal pointed in the right direction.

The new Liberal platform proposes to change that.

A new (unsustainable?) fiscal trajectory

In its last budget, the government committed to lowering the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2024–25 and keeping it on a downward path. It also pledged to shrink the deficit to less than 1 percent of GDP by 2026 and beyond.

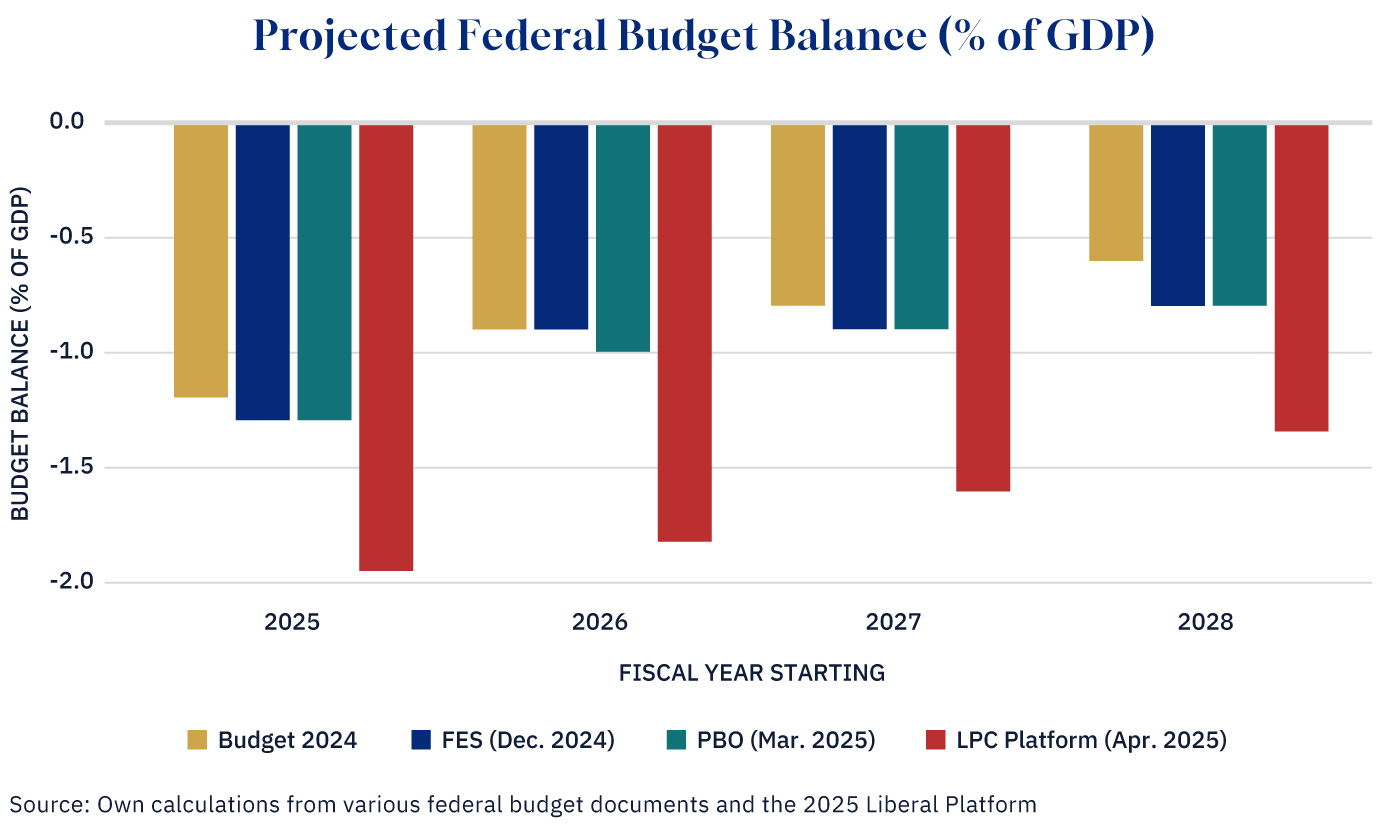

The party now hopes to achieve a deficit of 2 percent of GDP in 2025–26, falling only slightly to 1.8 percent the next year, then 1.6 percent, and eventually 1.4 percent by 2028. This is a sharp increase compared to previous projections—those in the last budget, the fall economic update, and even the Parliamentary Budget Officer’s most recent independent forecast—and it’s an even sharper increase from the government’s own plans from just over two years ago, when it projected a surplus by 2027.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Prior to COVID, Canada had not seen sustained deficits this large outside of recessions since the early 1990s.

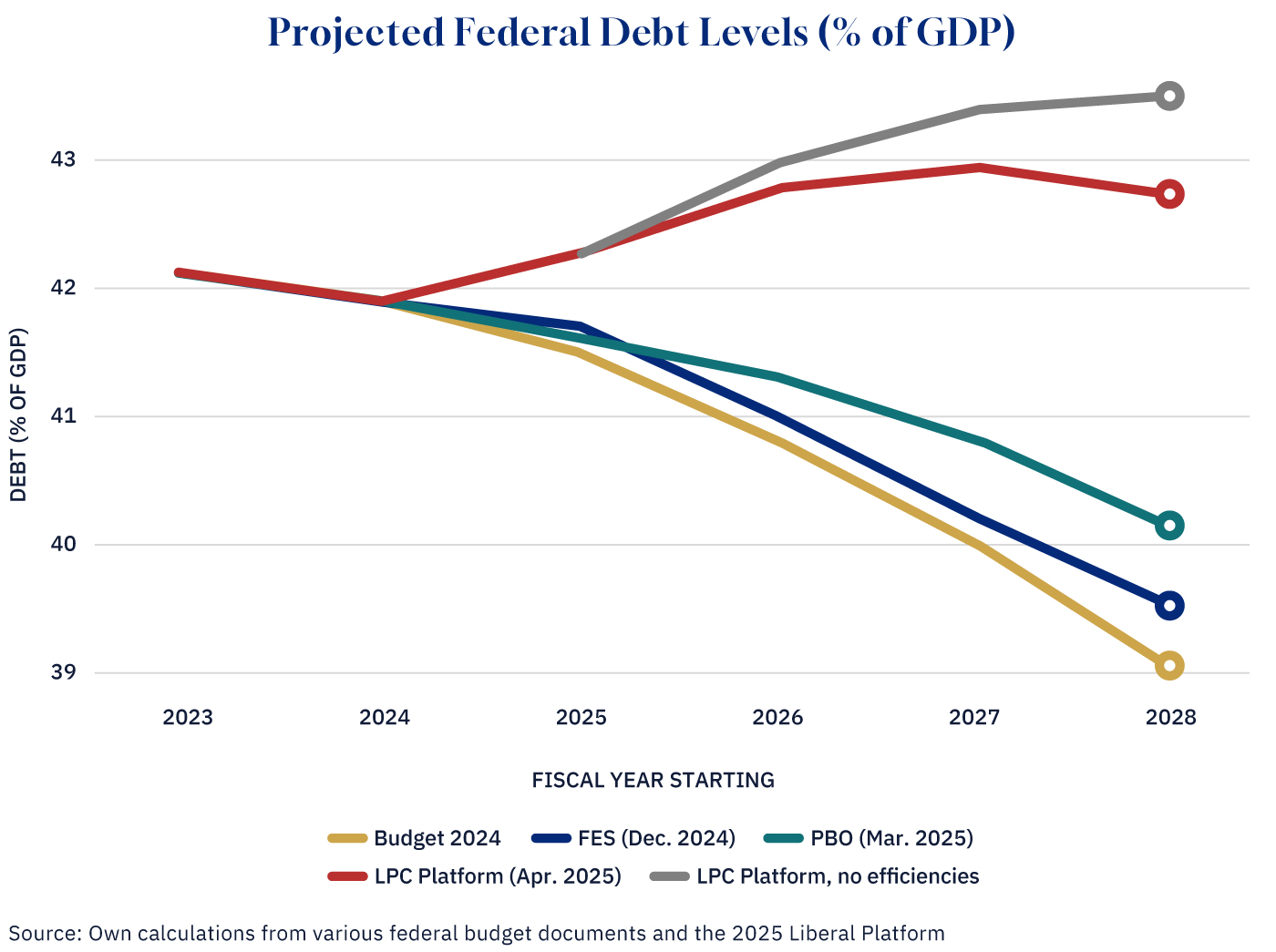

Rather than showing a decline in the debt-to-GDP ratio—from nearly 42 percent in 2025 to 39 percent by 2028—the new platform projects a rise to nearly 43 percent by 2027, with only a slight drop to 42.7 percent in 2028. That’s an increase of 2.6 percentage points of GDP compared to the PBO’s baseline, and 3.7 points above the government’s earlier budget plan.

These are not only large numbers, but the entire fiscal trajectory of the federal government is now pointed in a potentially unsustainable direction, as I illustrate below.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

This is not merely an abstract concept. Higher debt means higher interest costs—an estimated $2.3 billion more by 2028. Total federal interest payments that year will hit $68.7 billion, or about 15 cents of every tax dollar collected that year.

Looking under the hood

There are also reasons to doubt whether even these projections will hold. First, the economic assumptions behind them are potentially optimistic. Neither the last federal fiscal update nor the PBO’s baseline reflects the serious risks of a volatile economic and trade environment—especially important for a small, open economy like Canada’s.

If the downside economic scenario in the fall statement plays out—and the government sticks to its platform spending plans—federal debt could rise to about 44 percent of GDP by 2026, I estimate. Outside of the pandemic years, that would be the highest level since 2001. And even this downside projection does not truly represent what Canada’s economy would look like in the event of a full-blown trade war. After all, it features slower growth but no recession.

Second, the platform assumes the government will achieve productivity gains that will lower operating spending by $13 billion by 2028. Why that number? I can only speculate, but it turns out that these savings are the entire reason why deficits are projected to fall.

The platform shows a $62 billion deficit in 2025, dropping to $48 billion by 2028. But without those assumed gains in efficiency, the 2028 deficit would remain over $61 billion—basically unchanged.

Without those productivity gains, debt-to-GDP would rise each and every year in the plan, peaking at 43.5 percent in 2028, as I illustrated above.

Fiscal credibility at risk

This isn’t to say that the Liberal platform doesn’t contain worthwhile initiatives. This column isn’t weighing their merits or whether the benefits outweigh the costs of individual programs. Reasonable people can and will disagree about all of that.

Instead, I’m simply pointing out that the government’s previous fiscal anchors—declining debt-to-GDP and deficits below 1 percent of GDP—have now been clearly abandoned.

That’s a problem.

Frequent shifts in fiscal targets—regardless of party—can erode public and market trust in fiscal policy. And if markets lose faith in a government’s numbers, they price in more risk. That itself can raise borrowing costs.

Having a rising debt-to-GDP ratio built into the plan also weakens Canada’s fiscal flexibility. Public debt should act as a shock absorber in uncertain times. A declining ratio gave Ottawa room to respond to economic or geopolitical surprises.

And then there are the accounting changes the platform proposes.

It commits the federal government to run a “balanced operating budget” in 2028. It does this by excluding roughly $50 billion in capital spending each year over the next four years. But this figure is puzzling, at least to me. Statistics Canada puts actual federal capital spending at just $16.6 billion in 2023. So much of what the platform calls capital is probably just rebranded program spending.

Perhaps that’s not too surprising. Governments often label things as “investments” when they’re not. But the platform proposes to expand this relabeling from a comms strategy to formal fiscal policy. That risks muddying the waters around what the overall financial position of the government actually is and raises concerns about fiscal transparency.

The bigger picture

Deficit spending is not inherently bad. Public debt plays an important role as a shock absorber during recessions, for example. It rose by roughly five percent of GDP during the financial crisis and by 16 percent during COVID. It’s therefore important to lower debt levels after a crisis passes to prepare for the next inevitable shock.

In an increasingly uncertain global economy, and with no shortage of future demands on public finances—due largely to population aging and rising health care costs—Canada would benefit from a credible and sustainable fiscal strategy.

Unfortunately, this platform takes us further from that goal.