Canadian politics is entering a new, more American phase, with ideology and polarization playing a stronger role than ever before.

This might seem counterintuitive given that Canadian animosity towards America over Trump’s annexation and tariff threats was the defining issue of the election. But if we peer beneath the surface, a series of structural trends are apparent, in line with a broader realignment of politics across the Western world.

First, while Conservative leader Pierre Poillievre adopted a more populist style than his Tory predecessors Stephen Harper, Andrew Scheer, and Erin O’Toole, this does not appear to have harmed his performance. While the shock of Trump tanked Poillievre’s 20-point poll lead, it was largely the result of the left-wing vote consolidating behind Liberal leader Mark Carney. Poillievre won 41.3 percent of the popular vote, the highest of any Conservative in 40 years. He also increased the party’s total number of seats, preventing a Liberal majority.

The lesson here is that taking forthright stances, such as defunding the CBC, will not harm the party and could even motivate supporters to the polls. The more centrist approach of Scheer and O’Toole, by contrast, produced meagre results. This does not mean that extremism pays, but it does indicate that the party can risk putting clear blue water between itself and the Liberals.

Another striking aspect of this election is that the NDP collapsed to just 6.3 percent, its worst performance ever. This shows that the NDP’s identity and philosophy are only weakly differentiated from that of the Liberals. The Green decline reveals the same tendency. When there is a perceived threat, tactical voting kicks in, consolidating the NDP and Green vote toward the Liberals as the main progressive electoral vehicle.

We saw the same phenomenon on the Right with the PPC, whose vote share shrank from 5.1 to 0.7 percent.

The net result is that the two largest parties got 85 percent of the vote. Outside Quebec, the share is over 90 percent. Rather than a continental European system with multiple parties having distinct identities, this is beginning to look like an American pattern. The NDP is no longer a Western Protestant populist or trade union alternative, but merely a stronger version of the ideological Left than the Liberals.

Instead of people shifting between the Liberals and Conservatives based on performance and leader popularity, as was the case prior to the 2000s, they now move within ideological comfort zones but contained on the Right or Left, between the flank protest parties, whether NDP or PPC, and the main party in their ideological bloc.

There is another sense in which this consolidation looks American. U.S. politics has become increasingly polarized, with limited vote switching between the Republicans and Democrats across successive elections. Affective partisanship, in which voters feel very negatively toward the other side and positively toward their own, is a key feature of the system.

In an important study of polarization in Canada, leading Canadian political scientist Richard Johnston found that between 1988 and 2021, Conservative voters began feeling emotionally warmer on a 0-100 thermometer toward Conservatives and cooler toward the Liberals and NDP. The same trend held for the other parties, except that Liberals began feeling warmer toward the NDP and vice versa. Two ideological blocs were forming. With voters leery of supporting their ideological out-party, that pushes Canada toward the two-party result we see today.

Just consider how partisans in 2025 feel about other party’s leaders according to April 10-13 polling from Angus Reid. Fully 95 percent of Liberals and 93 percent of NDP voters have an unfavourable view of Poilievre, with some 75 percent of Liberal and NDP voters possessing a “very unfavourable” view of the Tory leader.

For Conservatives, 87 percent hold an unfavourable view of Carney, with 66 percent finding him “very unfavourable.” That is a Grand Canyon-sized divide by historical standards. On the other hand, there is comity between Liberals and the NDP: 51 percent of Liberals are favourable toward NDP leader Jagmeet Singh (who only garners a 48 percent very favourable rating from his own NDP voters), and 67 percent of NDP voters are favourable toward Carney. Again, this is evidence of polarization between a Left and Right bloc, with warmth within each coalition.

Pierre Poilievre and Mark Carney at the leaders’ debate in Montreal, April 17, 2025. Christopher Katsarov/The Canadian Press.

The importance of issues

In polarizing systems, voters are increasingly able to link issues to ideology, and ideology to party. What is interesting is the divides over the importance of particular issues in 2025. The Angus Reid data shows that 30 percent of Tory voters rank crime as a leading issue, compared to 9 percent of Liberals and 5 percent of NDP voters. Immigration is important for 23 percent of Conservatives, but just 7 percent of Liberals.

By contrast, the environment is an important issue for 21 percent of Liberals but only 1 percent of Conservatives. Forty-five percent of Liberals worry a lot about relations with the U.S. compared to just 21 percent of Conservatives. These are large divides.

On ideology, according to the most recent Canadian Election Study, 67 percent of Conservatives in 2021 identified as being on the Right, with 7 percent on the Left. NDP voters broke 49 Left to 22 Right, and Liberals 39 Left to 32 Right.

This might suggest Tories are outliers, but this measure reflects a relatively Left-leaning Canadian political culture. The growing warmth Liberal voters have for the NDP, and their coolness towards the Conservatives, as well as Liberal voters’ Left-leaning stance on many issues (when considered in an international context), suggests that Liberals are further to the Left than they perceive themselves to be.

The globalist-nationalist divide

A signature finding across the West is that electorates are realigning from a Left-Right economic split to a globalist-nationalist or “open-closed” cultural divide. Education level, which signifies cultural status and identity, therefore, becomes a more important demographic for voting. This is the case in Canada.

This year, the Angus Reid data from April shows that those making more than $100,000 split an even 44 to 44 percent between the Liberals and Tories, compared to 48 to 29 among those earning below $50,000, an income gap of between 4 and 15 percentage points, averaging 10. On education, however, university grads broke a whopping 58-25 for the Liberals over the Conservatives, and those with less than high school 45-39 in favour of the Conservatives, for a gap of around 20 points. That is twice as large as for income.

Youth and gender also tend to become important political cleavages, as value divides rise in salience in an electorate, while class and income become less important. A gender gap, especially among younger voters, is readily apparent in this Canadian election, as it was in the U.S. Across several polls, Canadian women went 48 to 36 for the Liberals over the Conservatives, while men preferred the Tories over Liberals 43 to 38. Canadians under 35, despite the narrative of Boomers backing Carney against the wishes of young people, did not consistently differ from older voters across the most recent polls. That is a weaker age gradient than in countries like Britain, but similar to the U.S. Young women are the strongest NDP demographic, and Carney managed to win over a considerable number of them.

The more politics moves from social class to ideology and from economic issues toward cultural concerns, the more zero-sum it tends to become. One of the most important issues redefining politics across the West is immigration. Canadian political scientists Stuart Soroka and Keith Banting show that immigration attitudes acquired a much stronger link to partisanship in Canada in the 2010s than in the period between 1980 and 2005.

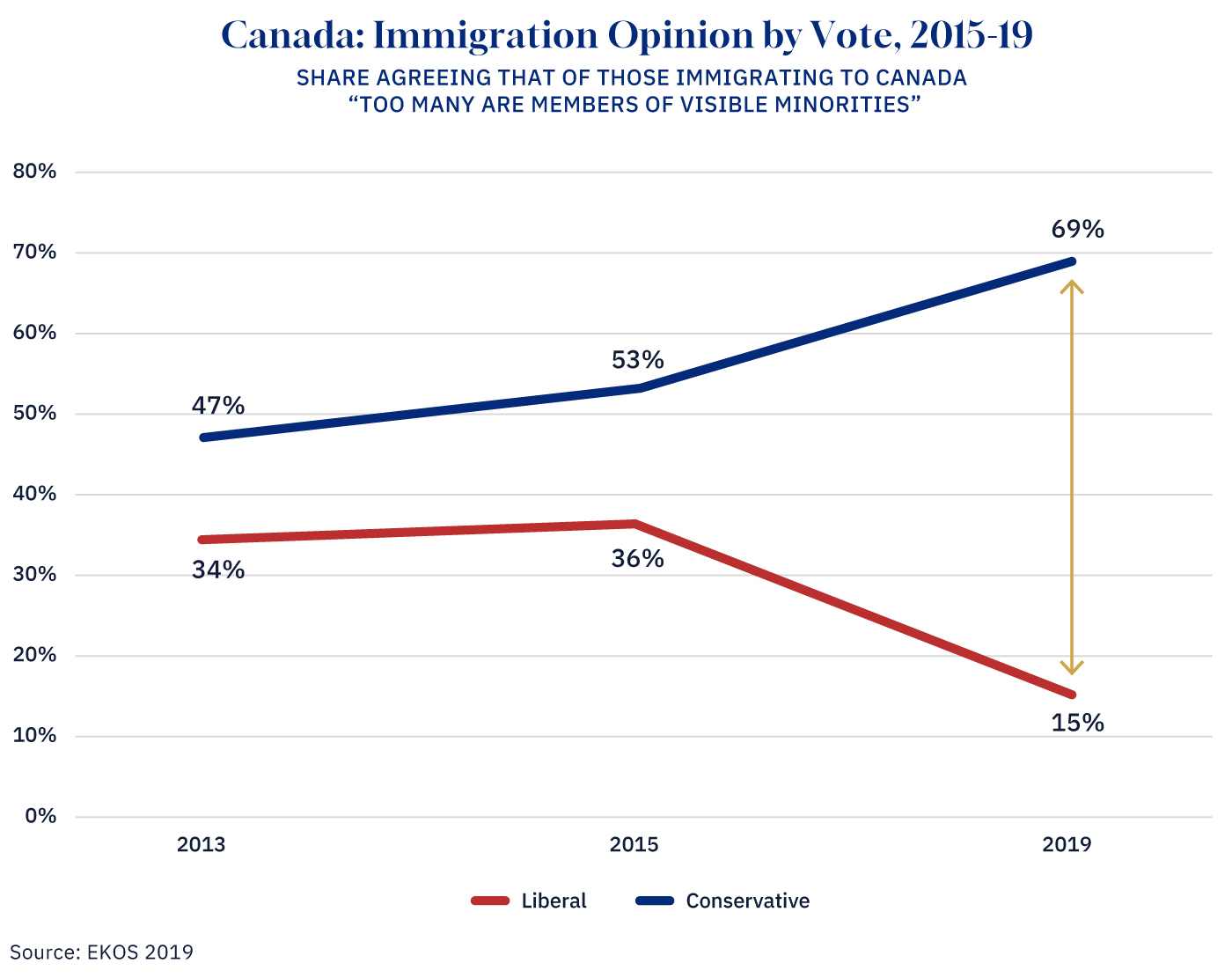

Figure 1 below, based on a series of EKOS polls, illustrates how views of immigration polarized along political lines in the late 2010s. Something similar occurred in the U.S. between 2012 and 2016 and, more slowly, in Britain between 2010 and 2019. In Canada today, there is a gulf in immigration opinion that was much less true before the 2010s, when the economic Left-Right divide dominated. Immigration opinion is connected to education level more than income, with non-graduate “somewheres” more aligned to the culturally conservative restrictionist position than the graduate “anywheres.”

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

The more “anywhere” cosmopolitan outlook is matched by differences in views on what political scientist Ron Inglehart calls “postmaterialist” questions, such as group equality and the environment. In the 2021 Canadian Election Study, the last for which we have data, around three in four prospective Liberal and NDP voters said that the federal government should spend more on the environment, compared to only one in three Conservatives.

On culture war questions, while Liberal women felt warmly towards feminists, giving them a 68 out of 100 rating (NDP women gave them a 73), Tory-voting women felt cooler, at just under 50. Where Liberals supported renaming buildings associated with those involved with residential schools by a 56 to 27 margin, this was opposed 56 to 29 by 2021 Conservative voters.

In a 2024 survey of culture war attitudes, I found that 65 percent of both Liberal and NDP supporters had a favourable view of Black Lives Matter, compared to 35 percent of CPC voters. Where 54 percent of combined NDP voters and Liberals said the pride flag should fly over government buildings, just 16 percent of Conservatives agreed. The values divide is stark and influences vote choice, even though these issues, along with immigration, were not discussed during the election.

This Canadian election shows a country sorting along ideological lines into two main blocs, each fronted by a major party. The Right has been steadily increasing its level of support since 2015, which may trigger a countervailing defensive response on the Left. All this will consolidate Canadian politics into a bipolar, U.S.-style pattern.