For the past few years, Pierre Poilievre was tuned into the Canadian mood with extraordinary precision. His pitch was shaped around a country gripped by a scarcity mindset—rising housing costs, strained health care, expensive groceries, and an overwhelming sense that the basics of life were slipping further from reach. It didn’t hurt that former prime minister Justin Trudeau was deeply unpopular and most of his detractors thought he made all of those things worse.

Poilievre’s political playbook was clear: speak to frustration, channel it into demand for change, and offer a blunt, unapologetic narrative of what’s broken and who’s to blame. It worked—until it didn’t.

On January 6, 2025, the story changed. Trudeau announced his retirement. Donald Trump had spent the previous month talking about Canada becoming the 51st state, and the mindset of the public began to change. And it changed fast.

Our polling at Abacus Data before, during, and after the federal election reveals something seismic: the mindset of Canadian voters shifted—from scarcity to precarity. In doing so, the criteria for leadership changed with it. Canadians were no longer only asking, “Can I afford rent and groceries today?” They were asking, “Will Canada still be Canada tomorrow?”

This isn’t just semantics. It’s a transformation of emotional and political logic. A scarcity mindset worries about immediate access to essentials; a precarity mindset fears that the systems ensuring those essentials—economic, health, social, geopolitical—may not hold at all. It’s a shift from stress to anxiety, from cost-of-living pressure to existential instability.

And it proved decisive in the outcome of the election.

How precarity upended the campaign narrative

We all know how this new story started. At the start of 2025, the Conservative Party was ahead of the Liberals by 27 points in Abacus Data’s first survey of the year. There was talk of the BQ forming the official Opposition, the NDP leapfrogging the Liberals, and the Liberals facing annihilation. Only 12 percent of Canadians believed the Liberals deserved to be re-elected. At the start of the year, our early polling still showed the question driving most voters was straightforward: who can fix what’s broken at home?

But then President Trump detonated a bomb that upended Canadian politics.

The announcement of new tariffs on Canadian goods, vague musings about annexation, and his belligerent framing of Canada as a geopolitical pawn all changed the context overnight. Canadians were suddenly being asked a different question: who can protect the country from this chaos and uncertainty?

That question didn’t play to Poilievre’s strengths. It demands not just indignation, but steadiness. Not just critique, but control. And in Carney, many Canadians found the kind of steady, calm, competent persona that precarity voters crave.

The data bears this out. In a March survey we conducted, 56 percent of Canadians said they were voting based on which party could best manage the Trump threat—a reversal from just weeks earlier, when 56 percent had said they were prioritizing domestic change. Among those driven by the Trump threat, the Liberals held a crushing 25-point lead.

This wasn’t just a shift in policy priority—it was a shift in mindset. And mindset, as we’re learning, may matter more than ideology.

Understanding the precarity mindset

My team at Abacus Data—led by my colleague Eddie Sheppard—started to notice a change in how people were talking about the world and the issues that mattered to them. We sensed a shift in mindset. So we worked to develop a five-level precarity index—from low to extreme—to better understand this shift. It measures how anxious Canadians are about system-level collapse: health care failing, jobs disappearing, institutions losing grip. It captures fears not just about today, but about the years ahead.

Precarity isn’t confined to any one demographic. Yes, younger Canadians and women are more likely to experience high or extreme levels of precarity. But what’s striking is that income has a weaker correlation than expected. Plenty of high earners feel precarious. In fact, it’s those who have something to lose—a job, a house, a pension—who often worry most about what could go wrong.

Here’s the political kicker: the more precarious someone felt, the more likely they were to vote Liberal in 2025. Among those in the extreme category, 55 percent voted Liberal and only 30 percent Conservative. For those with low precarity, the pattern flipped—66 percent Conservative, 27 percent Liberal.

The implication? Precarity made a Liberal victory possible, even among voters who otherwise desired change.

Liberal Leader Mark Carney makes a campaign stop in Upper Onslow, N.S., on Monday, April 21, 2025. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

Scarcity was Poilievre’s battlefield. Precarity was Carney’s

In hindsight, it’s clear that Poilievre was campaigning for the country we were in, while Carney was campaigning for the country Canadians feared we were becoming.

When Canadians were focused on scarcity—“my paycheque isn’t enough,” “prices are too high”—Poilievre’s message hit its mark. But precarity raises deeper questions: “Will my job exist in five years?” “Can I trust the system to be there for my kids?” “Is my country safe from foreign interference?”

This new mindset doesn’t just demand different policies. It demands different leadership traits. A precarity electorate looks for calmness, steadiness, reassurance. Carney’s central banker persona—dry, methodical, prudent—suddenly became an asset. It’s a rare moment in politics when boring becomes a feature, not a bug.

There’s a lesson here for Conservatives: if the public is frightened, angry doesn’t cut it. If the public is looking for safety, disruption can feel like danger.

Two roads from precarity: populism or collectivism?

The shift from scarcity to precarity also creates two possible political responses.

One is a populist reflex: close the borders, lash out at elites, promise a strongman who will protect “us” from “them.” This is the path that Trump himself represents. In other contexts—Hungary, India, parts of Europe—it’s proven potent. And has Poilievre flirted with elements of this posture, even if he’s never fully embraced it.

The other is a collectivist instinct: protect the whole, strengthen the centre, shore up the safety nets and institutions we all rely on. This is the road the Liberal campaign took—with appeals to national unity, “Canadian values,” resilience, and institutional strength. It was decidedly Canadian, nationalist, and patriotic.

What made 2025 unique was that the threat was external. Trump was the existential menace—not immigration, not climate policy, not internal division, and not Trudeau. And so, the collective reflex won out, albeit barely. When existential fear came from the outside and from a threat that exemplified the populist, conservative worldview, more Canadians leaned into community and competence, not what they perceived to be anger and blame.

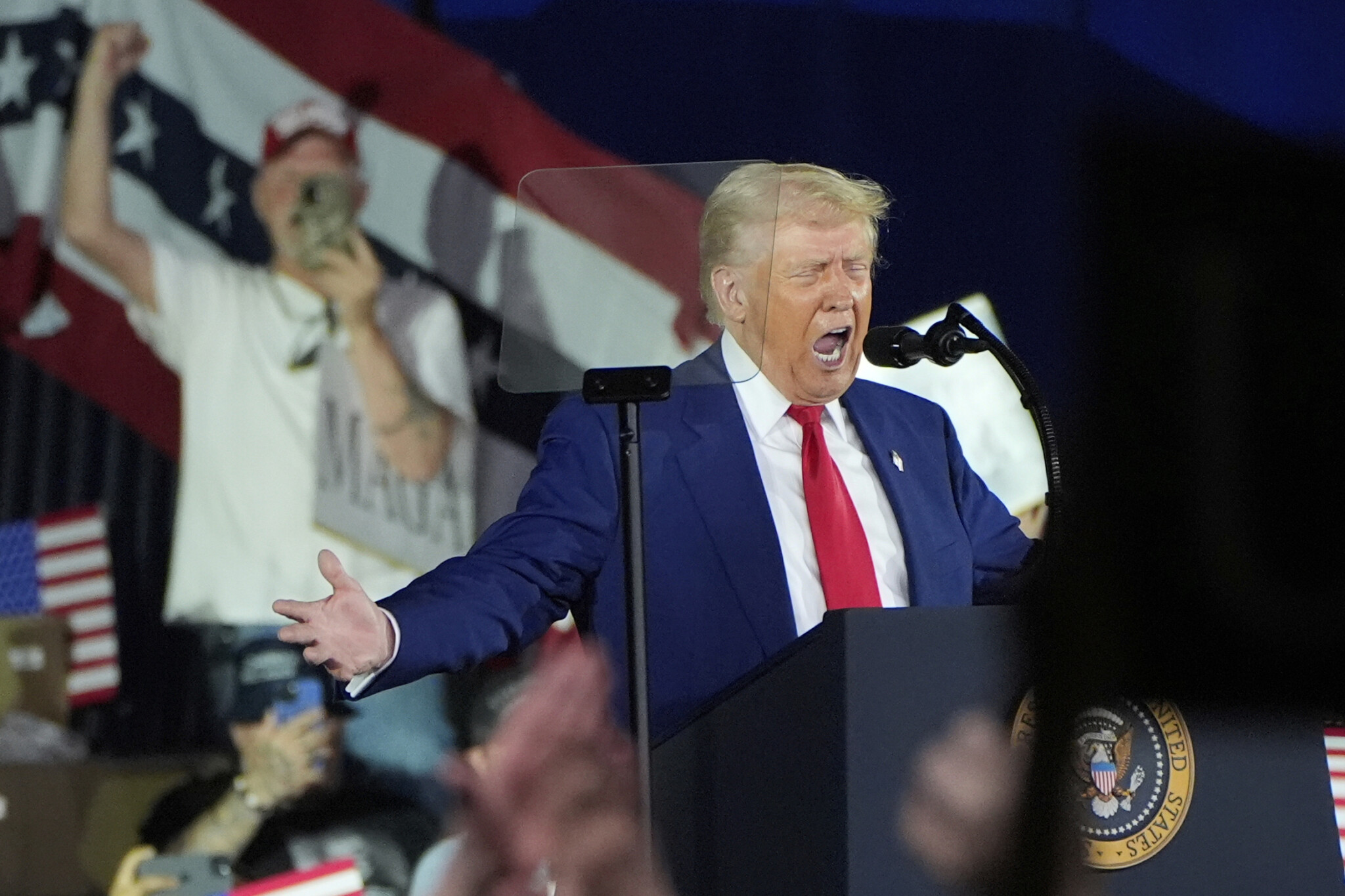

President Donald Trump speaks on his first 100 days at Macomb County Community College Sports Expo Center, Tuesday, April 29, 2025, in Warren, Mich. Alex Brandon/AP Photo.

This helps explain why, even among traditional Conservative identifiers, some crossed over. In our data, a subset of self-identified Conservatives told us they were voting Liberal, not out of newfound loyalty, but because the Liberals made them feel safer (think Baby Boomers). Precarity broke partisan habits.

What’s next for the Conservative Party?

So, what should Conservatives do now?

First, they must acknowledge that precarity is not a temporary blip. It’s a structural condition in Canadian public opinion. Our systems—economic, health, environmental, geopolitical—feel fragile. Until that changes, Canadians will continue to prize stability over disruption.

Second, they need to expand their toolkit. The Conservative Party cannot only offer grievances. It must offer protection. That means developing serious, credible policy on climate change, technological disruption (especially AI), trade resilience, and health-care capacity.

Third, the party must reconsider its tone and its talent. In a world defined by anxiety, voters want leaders who project calm, not just conviction. They want seriousness, not just passion. The 2025 election was not lost because of Poilievre’s ideas. It was lost because of his brand.

Security, calmness, and order—once the bedrock of conservative politics—have, for now, been claimed by the Liberals. That’s not inevitable. But reclaiming should be a top priority for the Conservatives.

The realignment isn’t over—but the Age of Rage might be

Just a few days after Canadians voted, Australians also cast their ballots in a national election. And the result? A centre-left Labor government—once deeply unpopular—was re-elected with relative ease. The opposition conservative coalition, which leaned heavily into Trump-style rhetoric and culture war themes, failed to connect (and its leader lost his seat, too). Despite economic frustrations and dissatisfaction with the incumbent, Australians opted for continuity, calm, and institutional stewardship over confrontation and disruption.

Sound familiar?

The parallels are striking. In both countries, a public that had once seemed primed for populist revolt instead chose leadership that promised stability in the face of global volatility. In both, the conservative alternative misread the public’s appetite—not for change, but for security.

Which raises a provocative question: is the so-called Age of Rage coming to an end?

For the past decade, politics in much of the West has been shaped by anger—against elites, against globalization, against systems that no longer seemed to serve ordinary people. That anger brought us Brexit, Trump, convoy protests, and a growing cynicism about democratic institutions.

But now, in the face of mounting precarity—climate shocks, geopolitical threats, inflation, automation, system strain—anger may be giving way to anxiety. And that shift brings with it a new political mood.

We may be entering the Age of Reassurance.

This is not a time for revolutionaries. It’s a time for rebuilders. The public is not looking for a battering ram. It’s looking for a builder with steady hands.

For Conservatives, this is both a challenge and an opportunity. The electorate still wants change, but not at the expense of stability. They want economic discipline, yes, but also social cohesion. They want borders protected, but democratic norms upheld. They want freedom, but not chaos.

If the Conservative movement in Canada—and around the world—wants to win in this new age, it must trade fury for focus, bluster for steadiness, and ideology for trust.

Because in an age of reassurance, calm is the new charisma.