DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. This particular DeepDive is made possible by FP Canada and readers like you.

As the House of Commons returns, parliamentarians have virtually no limit to the number of pressing issues that they must address. A major one should be the financial resilience of Canadian households.

It’s no secret that in recent years, many Canadians have struggled with day-to-day financial challenges related to affordability, cost of living, and broader strains on their household budgets. These issues persist and risk being exacerbated by ongoing trade action by the Trump administration. In the face of this heightened economic uncertainty, the goal of strengthening the financial resilience of Canadians has become paramount for supporting households and protecting Canada’s economy.

A growing share of Canadian households are already experiencing financial vulnerability. According to a 2024 report by the Financial Resilience Institute, 78 percent of households—representing nearly 20 million Canadians—were estimated to be experiencing financial vulnerability on some level. It’s notable also that based on measures like the household debt-to-income ratio or the household savings rate, Canadian households find themselves among the most financially vulnerable in the OECD.

This has a lot of major implications for households and Canada’s economy. The ability of households to withstand financial shocks is a key determinant of a financially resilient and strong and prosperous economy. Its benefits extend beyond individual households and contribute to a society’s long-term stability and the proper functioning of market economies.

Building financial resilience isn’t easy—there are no silver bullets—but as FP Canada’s research shows, it should be a priority for parliamentarians.

To support policymakers, it’s important that they have the latest information on the current state of financial vulnerability across the country. This includes its underlying factors and how they’ve evolved over time, how the situation compares to our peers, and a sense of how to strengthen our financial resilience. Indeed, understanding Canadian economic policy is impossible without a clear picture of the financial well-being of everyday citizens.

This DeepDive essay, produced in partnership with FP Canada, aims to address these issues. The goal is to provide a snapshot of Canada’s financial resilience and contribute to a policy discussion about how we can strengthen our resilience—particularly in a moment of significant economic risk.

Defining financial resilience

A well-articulated and peer-reviewed definition of financial resilience from the Financial Resilience Institute is:

“The ability of individuals, households, or businesses to withstand, adapt to, and recover from financial shocks, such as income loss, unexpected expenses, economic downturns, or rising costs of living, without experiencing long-term financial hardship.”

This concept encompasses several key elements:

- Income stability: Having steady and sufficient income to meet financial obligations.

- Savings and assets: Maintaining emergency savings and assets that can cushion against financial disruptions.

- Debt management: Keeping debt levels manageable to avoid financial strain during periods of economic stress.

- Financial literacy: Understanding and applying sound financial practices, such as budgeting, investing, and planning for the future.

- Access to support: Availability of social safety nets, credit, and community resources to help mitigate financial hardships.

Financial resilience is typically measured through indicators like savings rates, debt levels, income volatility, and the ability to cover essential expenses without external assistance. The OECD and World Bank often echo these sentiments and emphasize that financial resilience is not just about wealth but about the ability to adapt and recover from financial setbacks without severe long-term consequences.

A snapshot of Canadians’ income-to-debt ratios

For Canadian families, financial resilience—the ability to absorb economic shocks and maintain stability—has eroded in recent decades. Indeed, one in four Canadians are now unable to cover an unexpected expense of $500.

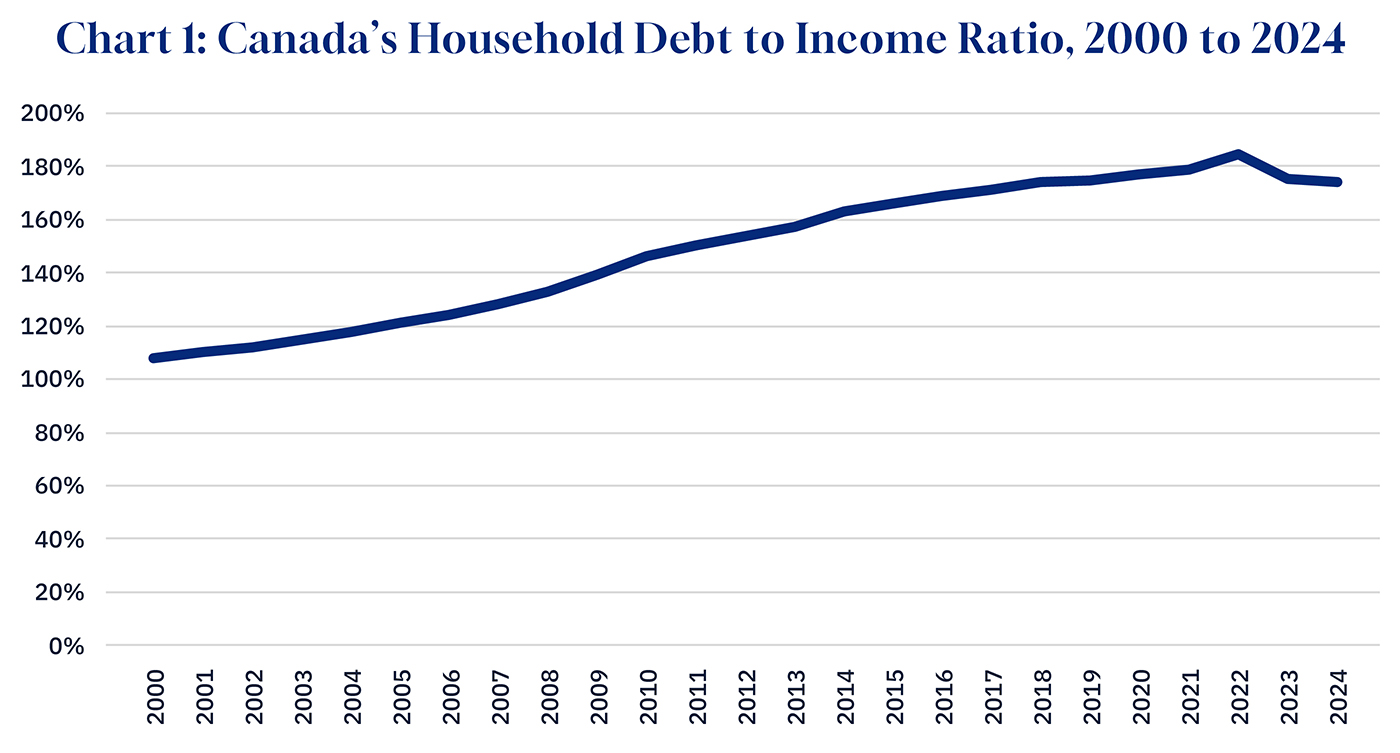

The most immediate concern is record-high household debt. As of 2024, Canada’s household debt-to-income ratio hovered around 175 percent, which puts it among the highest in the developed world. A combination of high mortgage balances, growing consumer debt, and rising interest rates has left many households vulnerable to economic downturns.

Consider a comparison with the United States. If Canada’s household debt-to-income ratio is 175 percent, that means that Canadians owe roughly $1.75 for every $1 of disposable income. By contrast, the United States household debt-to-income ratio is at 110 percent after experiencing a decline since the 2008 financial crisis. This represents a sharp departure from the 1990s, when household debt-to-income ratios in Canada and the United States were nearly equal.

Canada’s high household debt-to-income ratio has climbed rather consistently since the beginning of this century. In 2000, Canadian households were relatively financially stable. Yet there were signs that they were beginning to shift towards more credit-based consumption, with mortgages and consumer loans becoming more common. Soon, household debt levels started to surge.

Over the past two-and-a-half decades, declining interest rates, easy-to-access credit, and rising home prices have contributed to a nearly two-thirds increase in the household debt-to-income ratio (see chart 1).

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique set of challenges to household financial resilience. The economic shutdowns, job losses, and business closures caused a sharp recession in 2020. Federal emergency programs flowed an unprecedented $407 billion into the economy to help individuals and Canadian businesses stay afloat.

As the Canadian economy emerged from the pandemic, inflation became a major issue, with prices for housing, food, energy, and other essentials climbing rapidly. In response, the Bank of Canada raised interest rates sharply starting in 2022 to curb inflation, but this move exacerbated the financial strain on Canadians, especially those with high levels of debt. Mortgage holders with variable rates or those who need to renew their mortgages face significantly higher payments, leaving many households vulnerable.

Simultaneously, the cost of living in many urban areas, combined with the persistent affordability challenges in the housing market, has deepened the financial vulnerability of Canadian families. It’s notable that the highest household debt-to-income ratios are found in British Columbia and Ontario, which are home to the highest house prices. The gap between these provinces (approximately 200 percent) and Atlantic Canada (approximately 130 percent) is roughly 70 percentage points.

A growing number of Canadians, especially those in low- and middle-income households, are increasingly struggling to build savings, plan for retirement, or cushion themselves against unforeseen financial emergencies. Rising living costs, stagnant wage growth, and mounting debt burdens have created a perfect storm, leaving many families vulnerable and unable to secure their financial futures. Without meaningful policy intervention, this trend threatens to deepen economic inequality and undermine long-term stability.

Royal Bank of Canada Wealth Management (RBC) signage is pictured in Ottawa on Wednesday Sept. 7, 2022. Sean Kilpatrick/The Hub Canada.

Canadian household savings

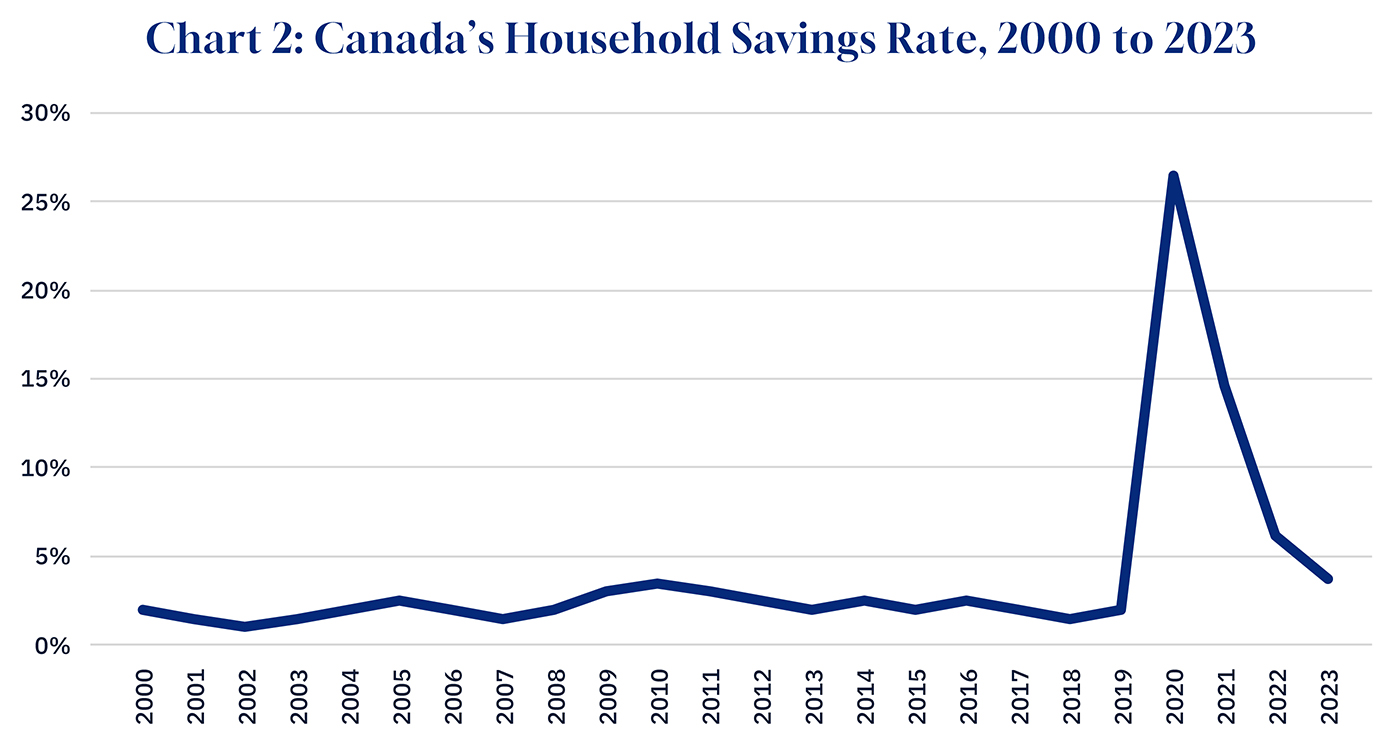

Combined with the stress reported above in the debt-to-income ratio for Canadian households, Canada’s household savings rate declined sharply in the early 2000s. While the savings rate hovered around 10 percent during the 1990s, it fell to just 2 percent in the new century. It has never fully recovered.

The 2008 financial crisis led to a temporary increase in savings, as households were more cautious about their finances. But in the years following the global recession, the savings rate averaged about 3 or 4 percent. By 2019, it was back down to just 2.4 percent, which was among the lowest in the developed world.

There was a pandemic-driven spike in Canada’s savings rate due to lockdowns, restrictions on spending, and government financial support. It reached as high as 27 percent in 2020. But it began to normalize thereafter. As restrictions eased and consumption patterns returned to normal, Canada’s savings rate fell back to roughly 4 percent (chart 2). High inflation and interest rates started to impact discretionary spending, while households also faced pressure from rising debt levels.

There’s a divergence across provinces when it comes to savings rates driven in part—though not fully—by housing prices. Alberta (8.8 percent) and Quebec (7.8 percent) both had savings rates that doubled the national average in 2023. British Columbia (0.6 percent) and Ontario (1.7 percent) were well below the national average. Nova Scotia was the only province with a negative savings rate due to higher consumption costs and rising debt servicing costs.

Disparities in Canadians’ financial resilience

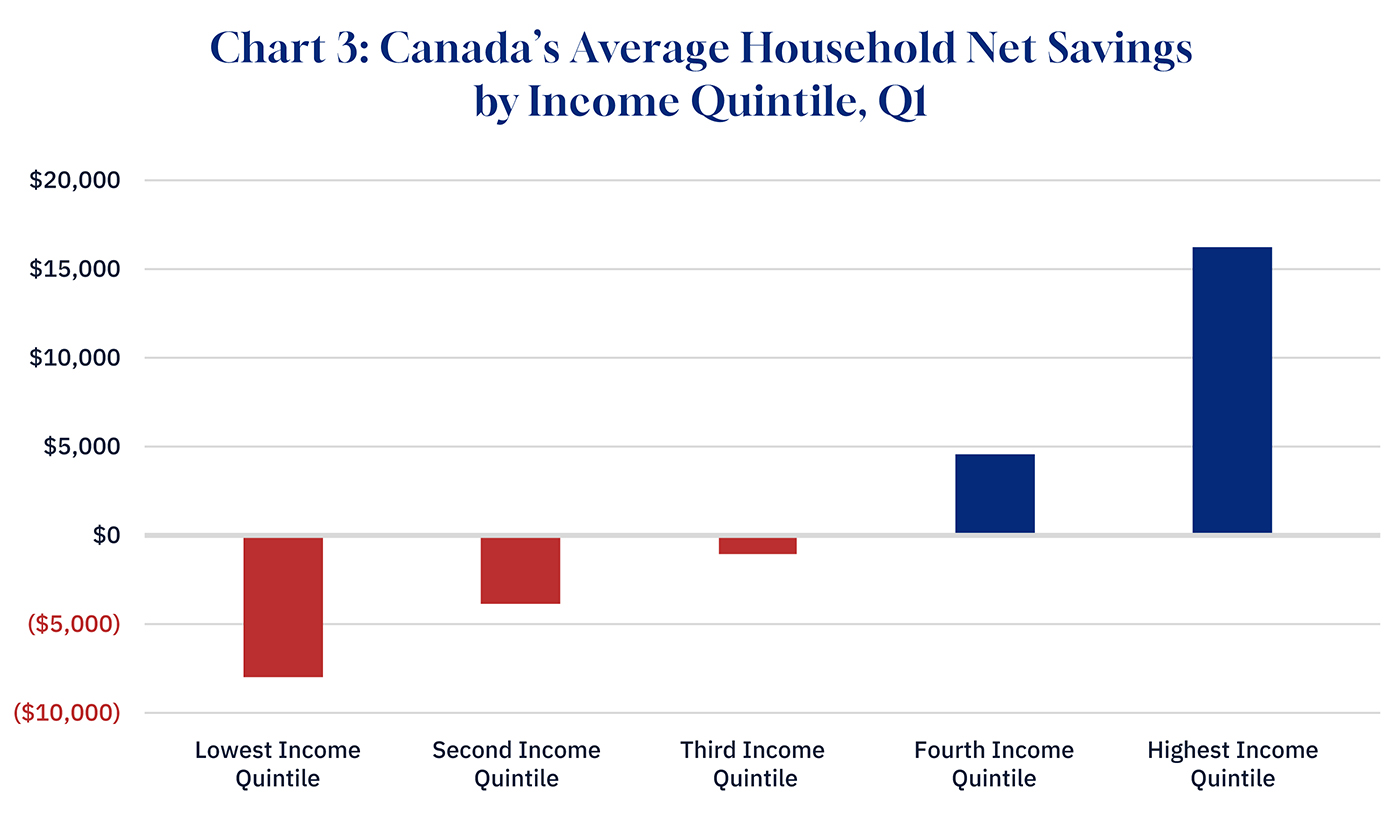

The financial resilience data reveals striking disparities tied to income levels, underscoring the uneven distribution of financial vulnerability across Canada. While higher-income households often have the resources to weather economic shocks, those in lower-income groups face significantly greater challenges, such as limited access to savings, higher debt burdens, and fewer opportunities to increase their incomes.

But these problems aren’t limited to low-income Canadians. For instance, data show that middle-income earners spent, on average, 17 percent more than their take-home pay in 2024, which amounts to a state of “dis-savings” (see chart 3). Those in the two lower income quintiles are facing even greater financial vulnerability.

The key point is that although financial resiliency is a broad issue, it’s especially critical for low-income households. According to one report, for instance, about one in three households in the lowest-income bracket is considered “extremely financially vulnerable.”

Canadians’ debt service ratios

Another measure of financial resilience is the household debt service ratio (DSR), which represents the proportion of income dedicated to paying debt obligations, including mortgage payments and other consumer loans.

Canada’s DSR has experienced a steady increase due to interest rate changes, inflation, and a shift in household incomes. During the early 2020s, historically low interest rates enabled many households to take on more debt, particularly in the housing market. However, as the Bank of Canada implemented rate hikes to combat inflation, borrowing costs surged, resulting in a higher proportion of household income being allocated to debt repayments.

The total DSR for Canadian households has gone from being relatively stable around 11 or 12 percent in the early 2000s to report all-time high of 15 percent in Q4 2024 and has remained persistently high ever since. This figure is notably higher than that of the U.S., where the household DSR is less than 10 percent. Several factors contribute to this difference, including higher levels of household debt in Canada, differences in mortgage structures (e.g., shorter mortgage renewal periods in Canada versus long-term fixed rates in the U.S.), and varying interest rate sensitivities.

Strengthening Canada’s financial resilience

Consumer spending is responsible for about 55 percent of Canada’s gross domestic product. A major shock to household consumption would have negative economic consequences. According to a 2022 cost-of-living survey, 86 percent of Canadians reported that rising household costs were outpacing their income growth. There’s a high risk that another economic shock—including a tariff-induced recession—would seriously threaten the financial sustainability of these households and the broader economy.

One way to address financial resiliency is a faster-growing economy. All things being equal, faster economic growth would contribute to higher labour demand and greater wage growth and job stability. Rising wages would in turn enable households to accumulate savings and reduce their financial vulnerability. Although some may argue that faster economic growth is merely captured by high-income earners, that notion isn’t quite consistent with theory and evidence. Economic growth typically boosts household income across the distribution and therefore enables consumers to pay down debt, save more, and build financial buffers.

The benefits of financial planning

Although a faster-growing economy is a necessary solution to household financial vulnerability, it’s an insufficient one. Governments must enact other policies to address the different factors that contribute to the lack of financial resiliency across the country.

Successive governments have enacted changes to mortgage rules to better ensure that borrowers can manage their payments in a higher interest rate environment. There have also been efforts to expand savings through voluntary savings programs, such as RRSPs or TFSAs, and a mandatory increase to the Canada Pension Plan. We have also seen various efforts to bolster financial literacy. These are positive steps.

But there is a growing sense that we should do more to strengthen household financial resilience. There has never been a more critical time to act.

A person walks past multiple for-sale and sold real estate signs in Mississauga, Ont., on Wednesday, May 24, 2023. Nathan Denette/The Canadian Press.

It’s important to remember that compared to the past two decades, Canadian households today are more indebted, spending a higher portion of their income on debt payments, and facing greater financial strain, particularly among low- and middle-income households. The saving rate has improved from pre-pandemic lows, but it remains well below the pandemic peak. And our household DSR is notably higher than that of the United States. It’s not hyperbole to say that Canadian households are among the most financially vulnerable in the OECD.

FP Canada has commissioned research on the key factors that can contribute to greater resilience for low- and middle-income Canadians. The research, including two white papers on the subject (of which many of the data points have been referenced in this essay), finds that financial resilience is a multifaceted challenge, demanding equally multifaceted solutions.

There’s considerable evidence that those Canadians who draw on the expertise of financial planning professionals to help them manage debt and plan for the future are better off. This is true across all income groups.

This is in large part because financial planning professionals can provide holistic support to their clients. This includes comprehensive advice encompassing all aspects of a client’s financial life, including investments, money management, taxation, insurance, budgeting, retirement planning, and so on. The research shows that those Canadians engaged with financial planning professionals tend to improve across all resilience categories, exhibiting positive financial behaviours that move them towards resilience and out of financial vulnerability.

Based on this research, FP Canada has been advocating with policymakers in Ottawa to consider solutions for improving the financial resilience of Canadians. In particular, FP Canada has put forward specific ideas on how government could help low- and middle-income Canadians obtain access to financial planning advice as one way to improve their financial resilience.

Key takeaways

As set out above, Canadian households face significant financial resilience risks. This in turn represents a significant macro and micro threat for Canada. It’s quite likely that a significant number of Canadian households could not sustain themselves through another pandemic or another major financial setback, such as a sustained trade war with the United States.

Strengthening household financial resilience should, therefore, be a key policy priority for Canadian governments. Achieving this objective will require leveraging a range of policy tools. A critical focus should certainly remain fostering robust economic growth, which in turn drives labour demand and supports higher wages.

However, it’s clear that more than ever, individual households in Canada are facing uncertain financial circumstances. Against this backdrop, it’s critical for policymakers to investigate and dedicate federal resources to strategies that will help Canadians build their financial resilience at the micro level.

We have presented here data that shows Canadians are struggling, and financial planners have been shown to be able to help. Although an engagement with a financial planning professional isn’t a silver bullet, the research shows that those who use these services tend to have greater financial resilience—across all income categories.

This DeepDive was made possible by FP Canada and the generosity of readers like you. Donate today.