DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

As we witness the first few weeks of the Carney government, we see that much of the political focus is inevitably on Donald Trump, tariffs, and trade. These are urgent and consequential issues, but they risk obscuring deeper and more enduring challenges at home. Governing effectively requires more than patching immediate leaks—it demands a clear understanding of the transformative period we are living through.

Prime Minister Mark Carney secured a mandate by persuading enough Canadians that he could navigate the immediate threat posed by Trump. But a more thoughtful reading of the moment recognizes that while Trump represents an imminent challenge, he is not a permanent one. The Biden presidency offers a cautionary tale: decline comes fast through the inexorable passage of time. Moreover, Trump’s presidency will be hastened by the probable reckoning of the 2026 midterms. Trump will shape the near future, but he will not define it.

Beneath the noise surrounding Trump lies a set of domestic fault lines that are reshaping the Canadian landscape—fault lines that demand more sustained attention from our leaders. As part of Pollara’s 40th anniversary retrospective, we will explore these emerging divisions. We begin with one of the most politically charged and socially consequential issues facing the country: immigration.

A political fault line around the world

Across advanced democracies and emerging economies alike, immigration has shifted from being a largely technocratic policy discussion to a deeply polarizing political issue. While many governments continue to promote immigration to address aging populations, labour shortages, and economic competitiveness, public opinion is increasingly moving in the opposite direction—driven by anxieties about culture, economic security, and social cohesion.

Here at home, Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre has labelled Canada’s population growth as “out of control” and called for “severe limits” to immigration.

In the United States, immigration remains one of the most divisive national issues. The southern border has become a symbolic and literal fault line, with Republicans under Donald Trump’s continued influence framing immigration as a threat to national identity, economic security, and law and order. Even as the U.S. economy remains heavily reliant on immigrant labour, public support has shifted toward tighter border controls and reduced immigration, especially among working-class voters. Democrats, for their part, remain internally divided, caught between humanitarian imperatives and growing voter unease.

Europe has experienced an even more dramatic shift. The refugee crisis of 2015 served as a turning point, catalyzing a surge of right-wing populism. Parties such as Alternative für Germany (AfD), France’s Rassemblement National, and the Sweden Democrats have gained momentum by explicitly opposing immigration—particularly from Muslim-majority countries—and framing it as a threat to Western values and social stability. Even historically pro-immigration states like Germany and Sweden have introduced stricter policies and emphasized integration over multiculturalism.

These policies are not the exclusive purview of right-wing parties. Denmark’s governing Social Democrats have expressed a vision for zero asylum seekers while pursuing third-country processing agreements, enforcing “anti-ghetto” legislation to dismantle “parallel” ethnic enclaves, and offering financial incentives for voluntary repatriation. Denmark’s centre-left coalition sought deportations to Rwanda even before the U.K.’s Tories.

Temporary foreign workers from Mexico plant strawberries on a farm in Mirabel, Que., Wednesday, May 6, 2020. Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press.

The U.K.’s Brexit was driven in large part by immigration concerns and highlighted the extent to which the issue can upend political orders. More recently, Prime Minister Keir Starmer has adopted an immigration policy that marks a clear departure from previous administrations. He has proposed a new Border Security Command to disrupt smuggling operations and reduce illegal crossings. Starmer also pledged to streamline the asylum system, eliminate the application backlog, and end reliance on hotels for housing claimants. While he maintains the post-Brexit points-based immigration system, he supports reforms to make it more responsive to labour market needs, especially in shortage sectors.

Australia and New Zealand offer a more cautious approach, using points-based systems to attract skilled migrants. However, rising concerns over housing, infrastructure strain, and visa abuse have recently prompted both countries to scale back immigration targets—part of a broader effort to align economic needs with domestic capacity and public sentiment.

In Asia, responses vary. Japan has begun admitting more foreign workers to address demographic decline, though public wariness persists. This shift comes after decades where Japan kept its borders tighter than almost any other country; in 2022, Japan accepted just 202 refugees compared to Canada’s world-leading 47,600, despite a population over three times as large. South Korea and Taiwan face similar pressures and have made limited moves to open their labour markets, with little progress on integration. Meanwhile, Gulf States like the UAE and Saudi Arabia continue to rely heavily on migrant labour without offering permanent status or citizenship, underscoring a clear divide between economic utility and national belonging.

Across all these regions, a set of interrelated themes consistently emerges. First is economic insecurity—a pervasive concern among citizens that immigration increases competition for jobs, housing, and public services at a time when many already feel financially strained. Second is cultural anxiety, particularly in societies with strong linguistic or ethnic majorities, where immigration is seen as a potential threat to national identity, social cohesion, and traditional values. Third, and perhaps most destabilizing, is the widening gap between political elites and the general public: while policymakers and business leaders often view immigration as a strategic tool for economic growth and demographic renewal, many citizens experience it as a source of disruption, fueling mistrust in institutions and resentment toward perceived top-down agendas.

The Canadian case

These same dynamics are becoming increasingly visible in Canada. Once praised globally as a model for successful immigration, the country has been slow to respond to mounting signs of strain. Economic pressures—including the rising cost of living, a deepening housing crisis, and overburdened infrastructure—are reshaping public attitudes. Cultural unease, particularly in Quebec and parts of Western Canada, is also growing. At the heart of this shift is a widening gap between federal immigration policy and the everyday realities of Canadians—a gap that poses growing political risks for leaders who fail to acknowledge or address public concerns.

Over the past five years, Canada’s immigration policy has evolved in response to these pressures. In 2022 and 2023, the federal government pursued aggressive immigration levels. These targets were almost entirely responsible for expanding the size of Canada’s population by over 930,000 and 1.27 million people a year, respectively, well above historical immigration levels. However, by 2023, public unease triggered a series of policy recalibrations. The government introduced caps on study permits and tightened work permit rules.

By 2025, overall immigration targets were reduced, with a sharpened focus on attracting skilled workers in sectors facing acute shortages. Regional programs were also expanded to direct newcomers to less-populated areas. Together, these changes represent a clear pivot from rapid expansion to a more selective, regionally balanced, and sustainability-oriented immigration strategy.

In this context, Canada’s recent turn toward skepticism is not an outlier but part of a broader international pattern. Canada is now grappling with the same forces that have reshaped immigration politics elsewhere. Our findings—highlighting rising discontent in Alberta, Ontario, and Quebec—underscore this shift. Immigration, once seen as a pillar of national strength and vitality, is increasingly viewed through the lens of government failure, cultural erosion, and economic insecurity.

New polling on Canadian attitudes towards immigration

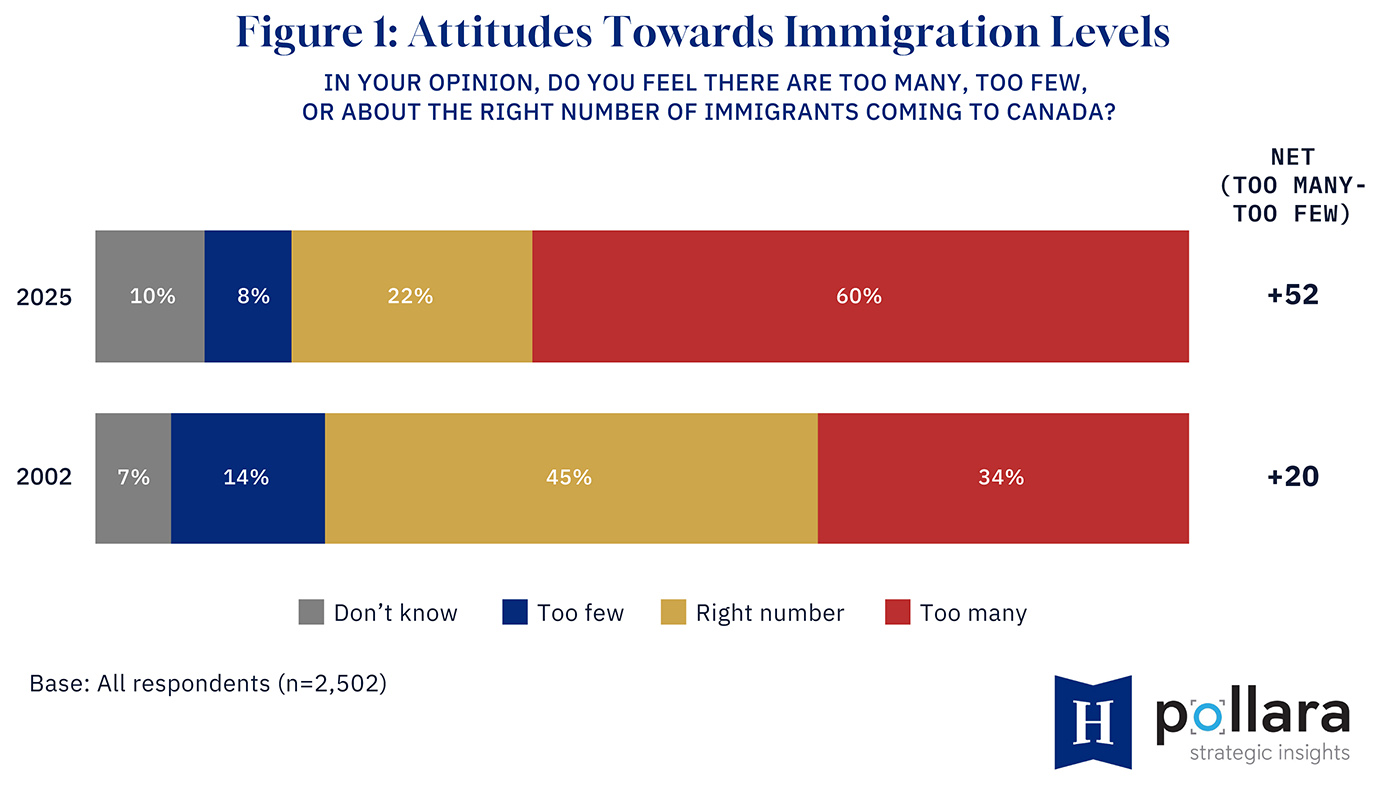

Pollara has been tracking Canadian attitudes toward immigration for decades, and to commemorate our 40th anniversary, we revisited this critical issue in a new national study. In a recent survey of 2,500 Canadian adults conducted from April 10 to 16, the most striking finding is the sharp increase in the number of Canadians who believe immigration levels are too high. When we first posed this question in 2002, only 34 percent held that view. Today, that figure has risen to 60 percent—a substantial 26-point jump that reflects a significant and lasting shift in public sentiment.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

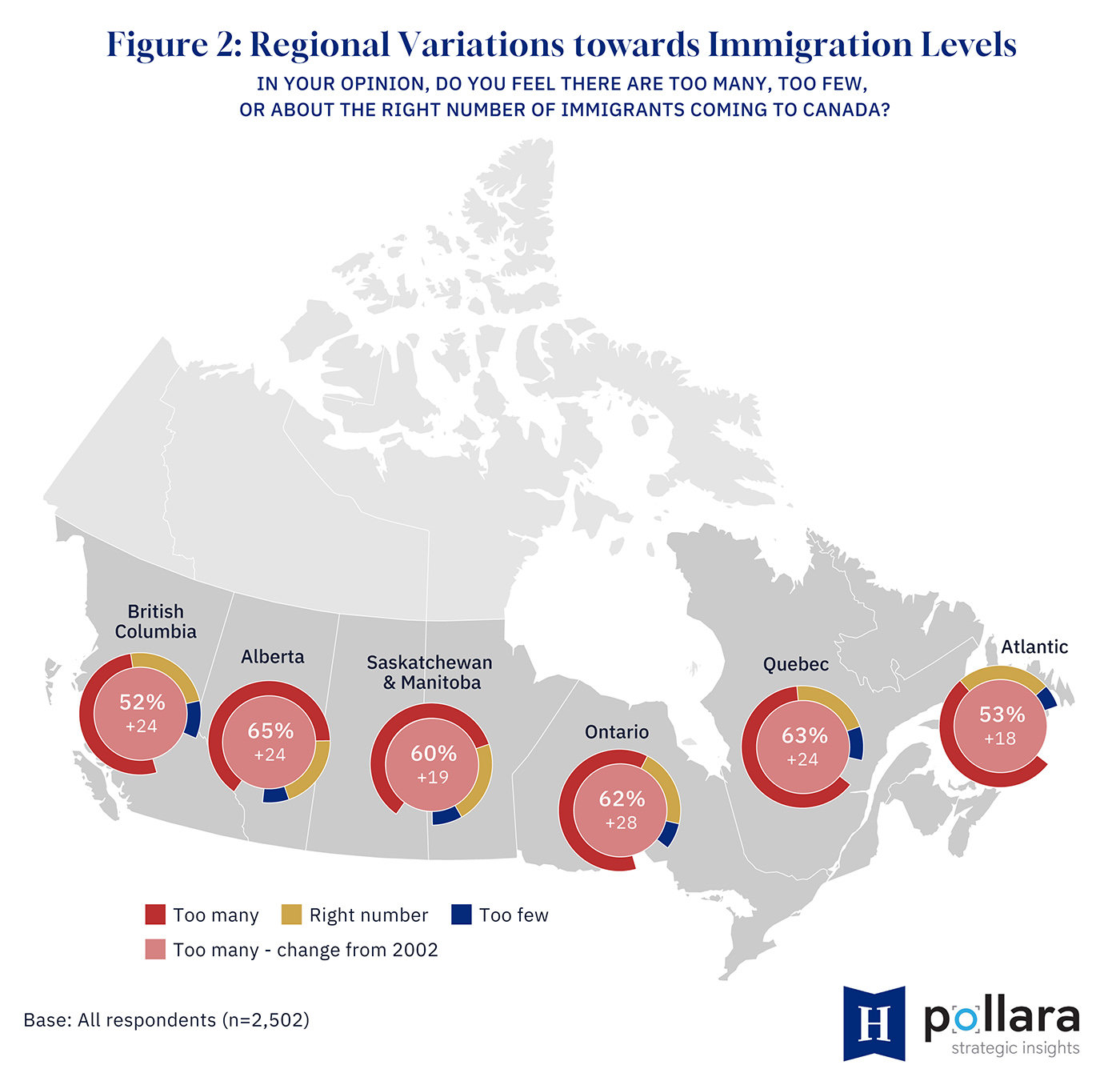

Alberta stands out as the most critical province, with 65 percent of its residents saying immigration levels are excessive. Quebec (63 percent) and Ontario (62 percent) also show high levels of concern, reinforcing a regional pattern that now poses significant political and policy challenges for the federal government.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Cultural anxiety and fractured identity

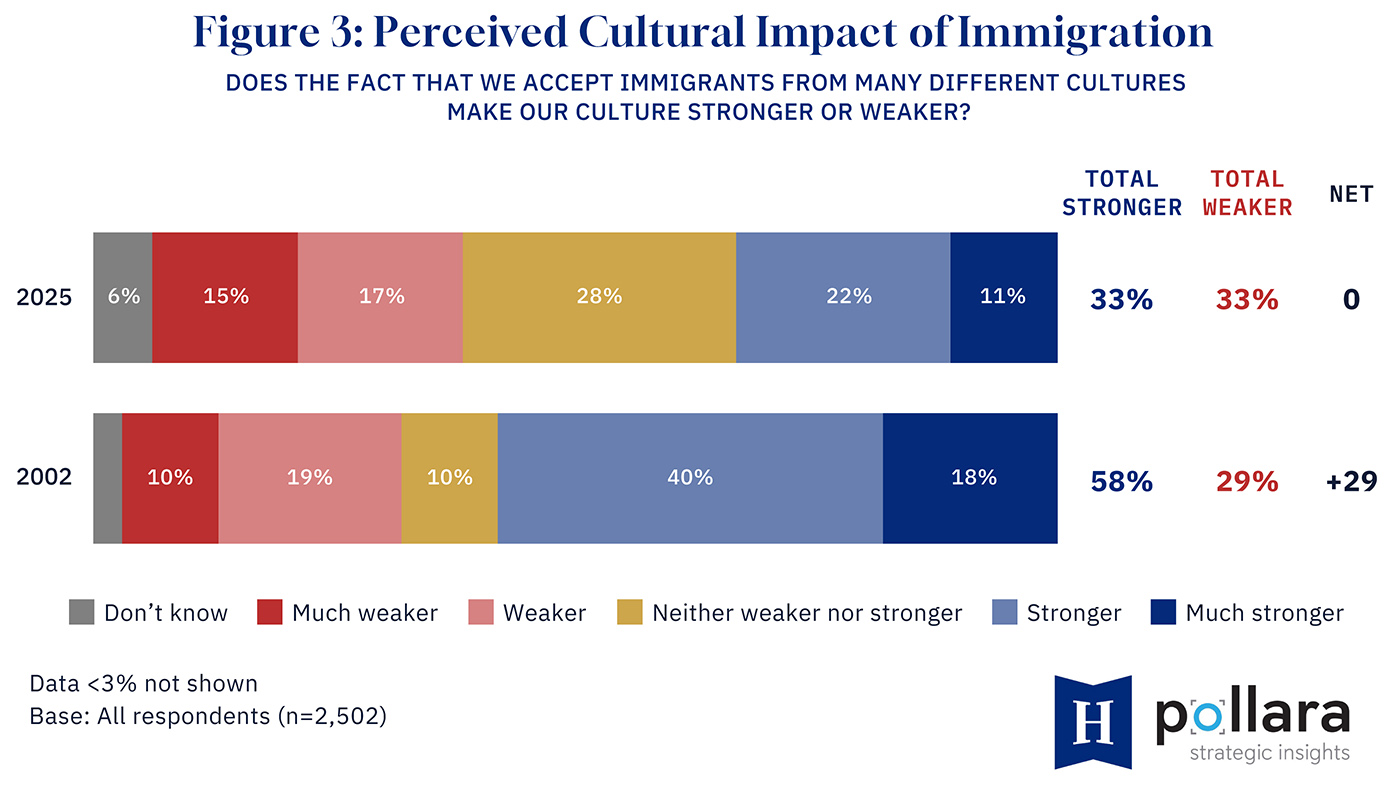

The study finds a growing unease about the cultural implications of immigration. In 2002, most Canadians (58 percent) believed immigration enriched the national culture. By 2025, this consensus has eroded: just 33 percent of Canadians now hold the same view.

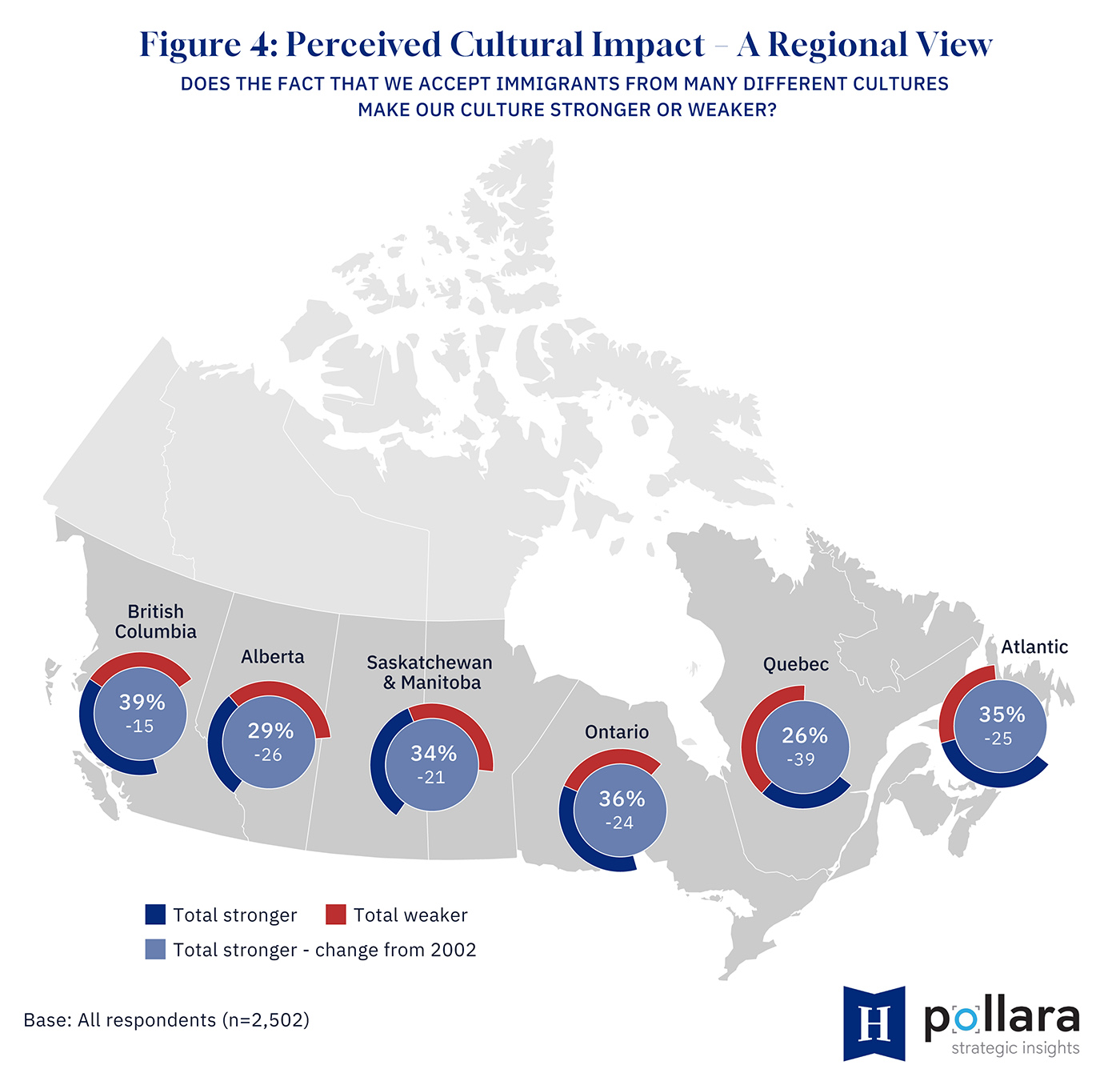

When examining the perceived cultural impact of immigration, the divide across regions is particularly striking in Quebec and Alberta.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Just 26 percent of Quebecers think accepting immigrants from different cultures makes our culture stronger, while 39 percent, the most of any province, think this weakens our culture. Alberta follows (29 percent strengthens/35 percent weakens), pointing to a notable undercurrent of skepticism towards multiculturalism. In contrast, more British Columbians (38 percent strengthens/31 percent weakens) and Atlantic Canadians (35 percent strengthens/28 percent weakens) express more favourable, if still cautious, assessments of immigration’s cultural contributions.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Signs of erosion

Economic concerns around immigration are more pronounced than ever. In 2002, 40 percent of Canadians believed immigration increased unemployment. Today, a majority of Canadians (52 percent) share the same view. Once again, we see interesting regional differences with Albertans (56 percent) being the most worried. Also, Canadians with college or high school education (55 percent) are particularly concerned about the impact of immigration on unemployment.

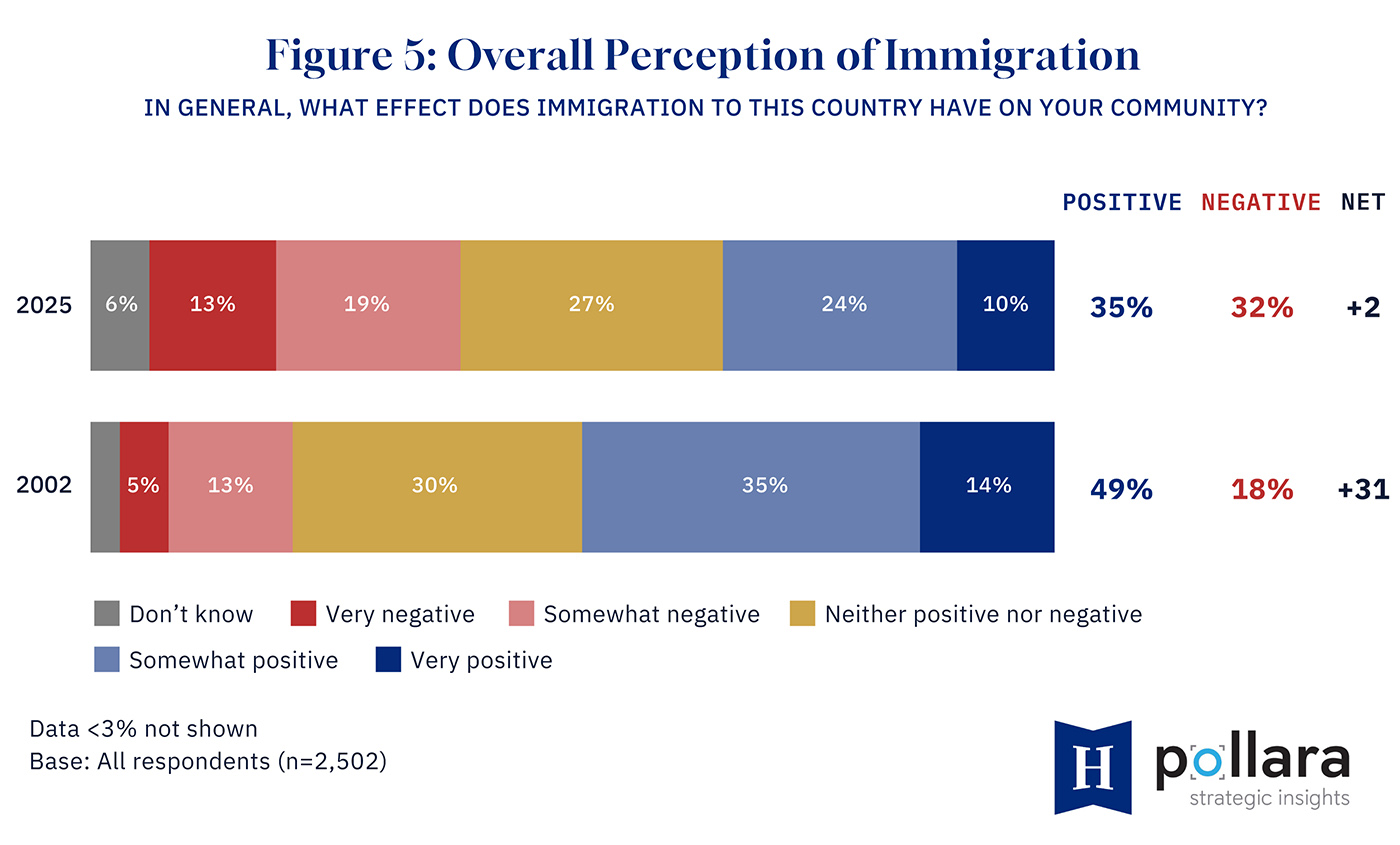

In the same vein, the overall impression about immigration has soured. When asked, “In general, what effect does immigration to this country have on your community?” almost half of Canadians (49 percent) back in 2002 felt positively. Twenty-three years later, only about one-third (35 percent) feel the same way.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Key takeaways

This erosion of trust in immigration carries direct and growing consequences for the Carney government, which must now navigate a political landscape where support for immigration can no longer be assumed as a default consensus. For years, Canada’s pro-immigration stance was widely seen as a point of national pride—an expression of openness, pragmatism, and multicultural identity. But that consensus is beginning to fracture. Rising economic pressures, strained public services, and growing cultural anxiety have altered the public mood. What was once a source of political unity is now becoming a point of division.

The Carney government’s electoral focus on the external threat posed by Trump—while understandable and effective in mobilizing voters—has come at the cost of deeper engagement with emerging domestic tensions. The Trump issue remains real and immediate, particularly in the realms of trade, national security, and global democratic stability. But as the old saying goes, “This too shall pass.” The danger lies in mistaking a temporary crisis for a permanent framework of governance.