DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. This particular DeepDive is made possible by Rio Tinto and readers like you.

Amid a chaotic geopolitical and economic agenda, the G7 leaders meeting in Kananaskis this past week found time to develop a joint statement on critical minerals. The statement represents one of the clearest and most significant expressions of the economic and strategic importance of key minerals.

As they said:

We, the Leaders of the G7, recognize that critical minerals are the building blocks of digital and energy secure economies of the future… We have shared national and economic security interests, which depend on access to resilient critical minerals supply chains governed by market principles. We recognize that non-market policies and practices in the critical minerals sector threaten our ability to acquire many critical minerals, including the rare earth elements needed for magnets, that are vital for industrial production. Recognizing this threat to our economies, as well as various other risks to the resilience of our critical minerals supply chains, we will work together and with partners beyond the G7 to swiftly protect our economic and national security. This will include anticipating critical minerals shortages, coordinating responses to deliberate market disruption, and diversifying and onshoring, where possible, mining, processing, manufacturing, and recycling.

The G7 statement is a reminder that Canada is well-positioned to be a global leader, not just as an “energy superpower,” but as a natural resources superpower that brings energy, critical minerals, and manufacturing together in a resilience-oriented industrial strategy.

Realizing this opportunity will, of course, require a greater appetite for risk and changes to policy frameworks for how we assess and finance major critical minerals projects, from mines to processing to manufacturing, some of which are already underway. We also must link our strategy to global dynamics around geopolitics, technology, population growth, and climate change, as suggested in the G7 leaders’ statement. Too often, our natural resources strategy has been inward in orientation, mired in domestic squabbling, and failing to respond to shifts in global capital markets and the competitive landscape for critical minerals and energy.

There’s also a need to recognize the interrelationship between Canada’s natural resources and other parts of the economy. Critical minerals and affordable, reliable energy are essential and mutually-reinforcing inputs for Canada’s manufacturing sector. Low-cost energy and a growing supply of critical minerals will be mutually reinforcing and vital assets at a time when industrial production is under assault from U.S. protectionism and relentless cost pressure and competition from Asia.

A resilience-oriented industrial strategy should thus be understood as a policy agenda designed to leverage Canada’s natural resources for economic and geopolitical advantage and boost domestic growth and resilience, including in the manufacturing sector. In particular, such a strategy should involve a combination of public-private partnerships, Indigenous economic reconciliation, and support for innovation.

Canada and the global natural resources sector

Canada’s natural resources sector exists in a global context. Prices of most commodities are set globally and traded in markets from Shanghai to London to Dubai. Our resources sector is dominated by multinational firms that invest on a risk-adjusted return basis globally, targeting the most economically valuable resources and projects with the lowest political risk. Even Canadian-based multinationals, from Nutrien to Agnico-Eagle to TC Energy, invest across jurisdictions in this manner.

Geopolitics can be a massively disruptive factor in the allocation of global capital to the natural resources sector, as countless examples illustrate. The outlook for Canadian LNG completely turned in 2022, based on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the following sanctions and supply disruptions that sent EU and Asian buyers scrambling for new supply. Canadian aluminum producers have had to grapple with two rounds of U.S. Section 232 tariffs, first in 2018 and again this year. Canadian canola producers have endured collateral damage from trade and geopolitical tensions with China, most recently in the form of retaliation to Canadian tariffs on Chinese-made electric vehicles.

Technology, too, is a massive global disruptor for the Canadian natural resources sector. Consider the plunge in global solar panel costs or the rapid uptake of EV technology in China’s transportation sector. These changes don’t need to be global in scope to influence demand for traditional fossil energy or create booming demand for the minerals that are integral to their production.

No government or industry leader has a crystal ball, so how can the Carney government plan for future global geopolitical or technological disruptions? Resilience is the appropriate frame to manage future shocks. Key principles of resilience should include a portfolio approach that avoids unhedged risks, secures international partnerships, and leverages existing strengths in the Canadian natural resources sector and its underlying policy framework.

For critical minerals, avoiding unhedged risks translates into a balanced strategy accounting for upstream and downstream as well as different types of minerals. A strategy that went all-in on lithium and EV batteries may have looked good in 2022 but does not look good in 2025 following a slump in North American EV demand and a scale back of consumer incentives and mandates in the U.S. Conversely, a high-tech oriented mineral like graphite was an afterthought in 2021 but looms large in 2025 following a series of Chinese export restrictions. A portfolio approach is essential as different minerals will face different macro demand drivers and threats from foreign competition and innovation-driven substitution over time.

Government can play a key role in helping industry ride through downturns and external shocks that can be difficult for private investors alone to withstand. This doesn’t mean bailouts but rather keeping policy signals and incentives consistent and aligned with longer-term objectives. The Carney government will have the opportunity to reset and reinforce these policy priorities, including continuity in decarbonization and electrification of the economy alongside a greater commitment to building economic resilience and finding new markets for natural resources and manufactured goods.

The Compass Minerals Salt mine sits at the mouth of the Maitland River on Lake Huron in Goderich, Ont. on Thursday, July 18, 2024. Geoff Robins/The Canadian Press.

Canada should also balance its critical minerals policy across the value chain. Canadian governments have supported significant investments in downstream projects focused on batteries, battery materials, and EV manufacturing. There’s much less tangible to point to in terms of results on new mining and minerals processing activity. These well-intended investments have left our critical minerals strategy imbalanced to the consumer-facing side of the market, with less presence as a global upstream mining and processing player.

Successful mega-development of mining and processing projects in areas such as gold, uranium, and potash may provide a path forward for critical minerals, particularly with respect to greenfield projects that must be world-scale to compete for capital. Yet there will also be upstream opportunities focused on brownfield redevelopment and secondary recovery, smaller-scale projects for rare earth elements and other “niche” but strategic minerals, and a renewed focus on recycling and circularity. Canada has already led the way in this type of project with Rio Tinto’s development of scandium oxide recovery from its titanium dioxide waste streams in Quebec and Teck Resources’ recovery of germanium from its zinc processing in British Columbia. There are also promising pathways led by CVW Cleantech to extract valuable critical minerals from oil sands tailings in Northern Alberta.

Downstream partners can provide upstream financing for these projects, combined with government and Indigenous financial incentives, including critical supports for R&D in the mineral and metal processing space, which is essential to close the technology gap with Chinese competitors.

Canada must continue to look abroad for critical minerals partnerships. The U.S. critical minerals executive orders and the Trump administration’s approach to energy dominance have a strong Buy America focus, putting Canadian access to U.S. government procurement markets and incentives for critical minerals at risk. Section 232 tariffs on steel and aluminum, of course, add an even greater wedge in the relationship. While the underlying logic and economic reality of deep Canada-U.S. integration on metals and minerals may re-emerge, there is little downside to strengthening alternative markets.

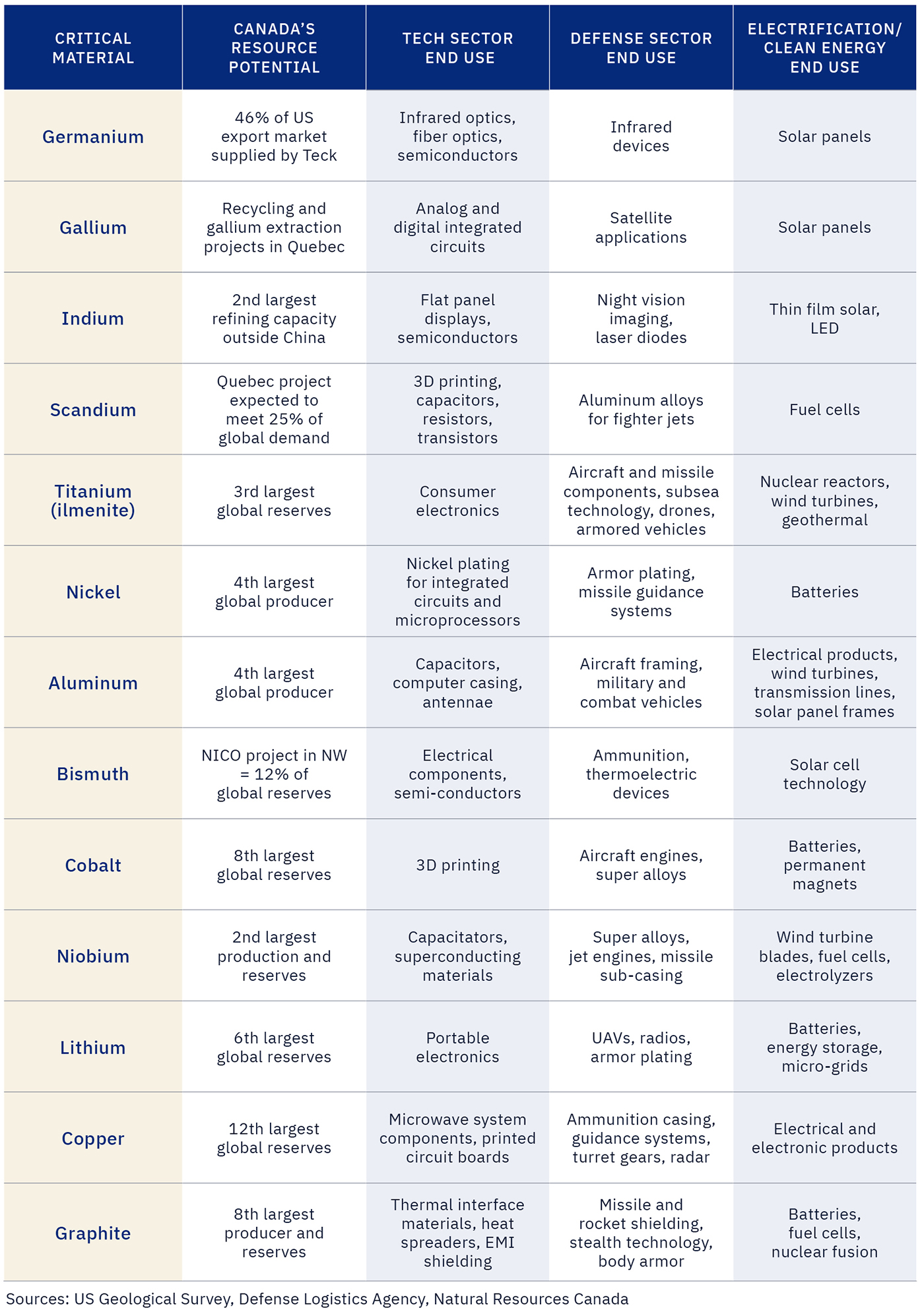

Diversification from China’s dominant position in critical minerals processing is a core goal for other OECD markets, both for pricing power concerns and often for geopolitical reasons as well. Canada cannot replicate everything China has done, but it makes sense to pick our spots. Strategic investments in lower volume but highly strategic minerals like rare earths, the “three G’s” of graphite, gallium, and germanium, or critical military inputs like titanium or zinc, align with the Canadian resource base and will have a high impact, particularly when integrated with processing. The table below provides potential Canadian “anchor” critical minerals and materials for key end-use sectors, from technology to defence to clean energy.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Canada should, within this context, focus on building a critical minerals club that the U.S. would want to be a part of. Issues such as reducing dependence on Russian energy and materials, international cooperation on supply chains, and building out minerals-intensive clean energy and electricity infrastructure will remain priorities for the G7. U.S. support for these multilateral approaches is uncertain, but Canada and its European and Japanese G7 partners need to show substantive, project-focused action that will help draw the U.S. back to the table. This could include G7 partnership and support for U.S.-led investments that leverage Trump’s recent commitment to expanded funding for the Development Finance Corporation and Ex-Im Bank.

Lastly, Canada should draw upon existing strengths in our natural resources sector, while working to mitigate well-known vulnerabilities around permitting timelines, cost overruns and low productivity, and a scarcity of patient capital for major natural resources projects. Key strengths include consolidating and building upon recent progress in economic reconciliation with First Nations, well-functioning regulation and markets for industrial GHG emissions, and the potential to deploy large-scale, clean baseload power for critical minerals processing and other energy-intensive heavy manufacturing and materials production.

None of these strengths can be taken for granted, and recent gains could easily be lost due to policy shifts. Such shifts could include a federal and/or provincial project assessment overhaul that weakens Indigenous consultation, or a breakdown in the industrial carbon price regime that limits the ability of project developers to create and monetize predictable revenue streams related to carbon credits.

Canada will need to develop additional long-distance transmission capacity that could connect future industrial mineral processing zones in Alberta and Saskatchewan, for example, to hydro power in B.C. and Manitoba. CO2 capture and storage infrastructure in the prairie provinces would be well suited to accommodate emissions from minerals processing and refining. Low-to-zero-emission processing facilities, combined with Canada’s already existing low CO2 grid intensity, would position Canadian processed minerals and materials for a carbon border adjustment mechanism-type future in EU or northeastern Asian markets.

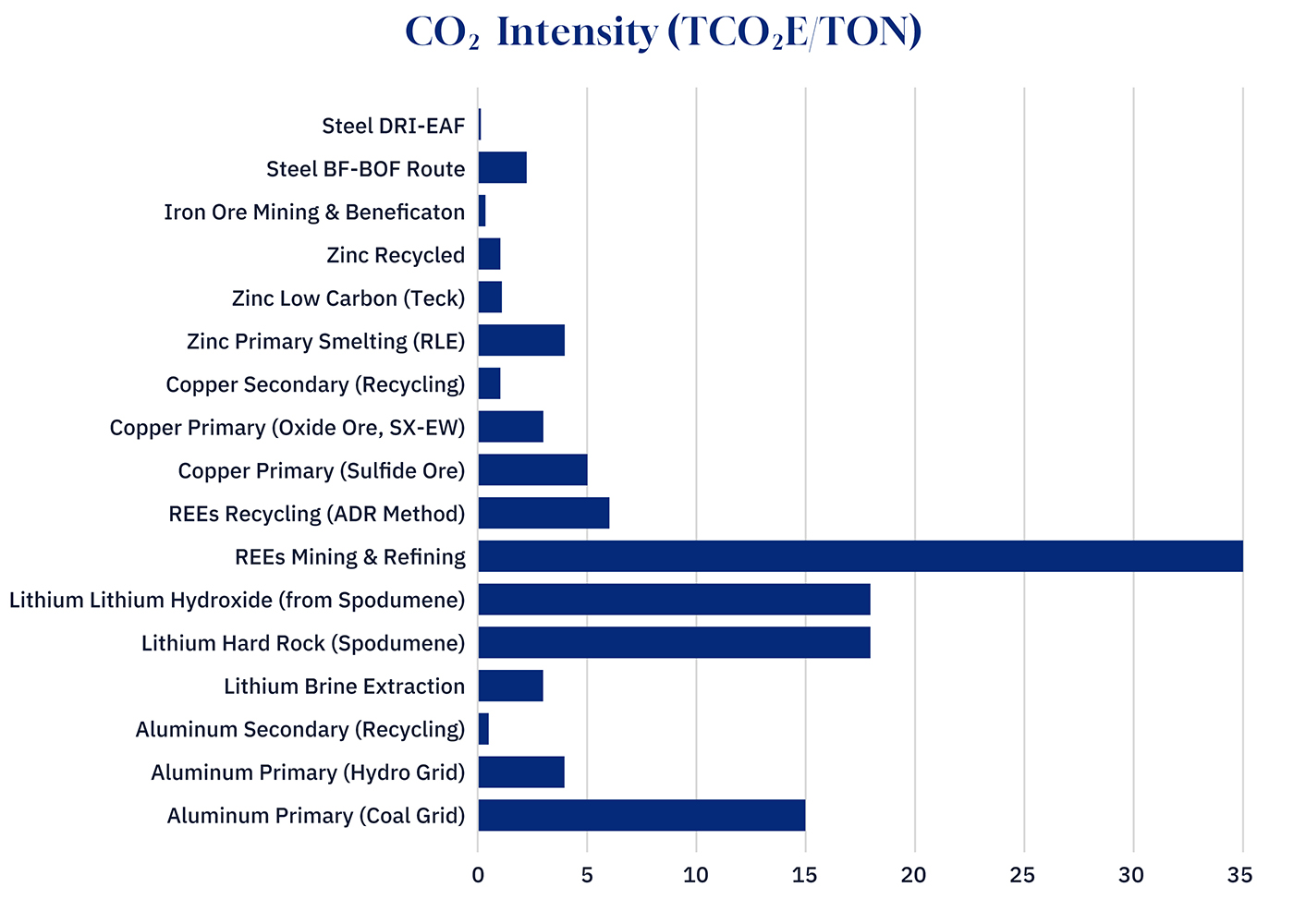

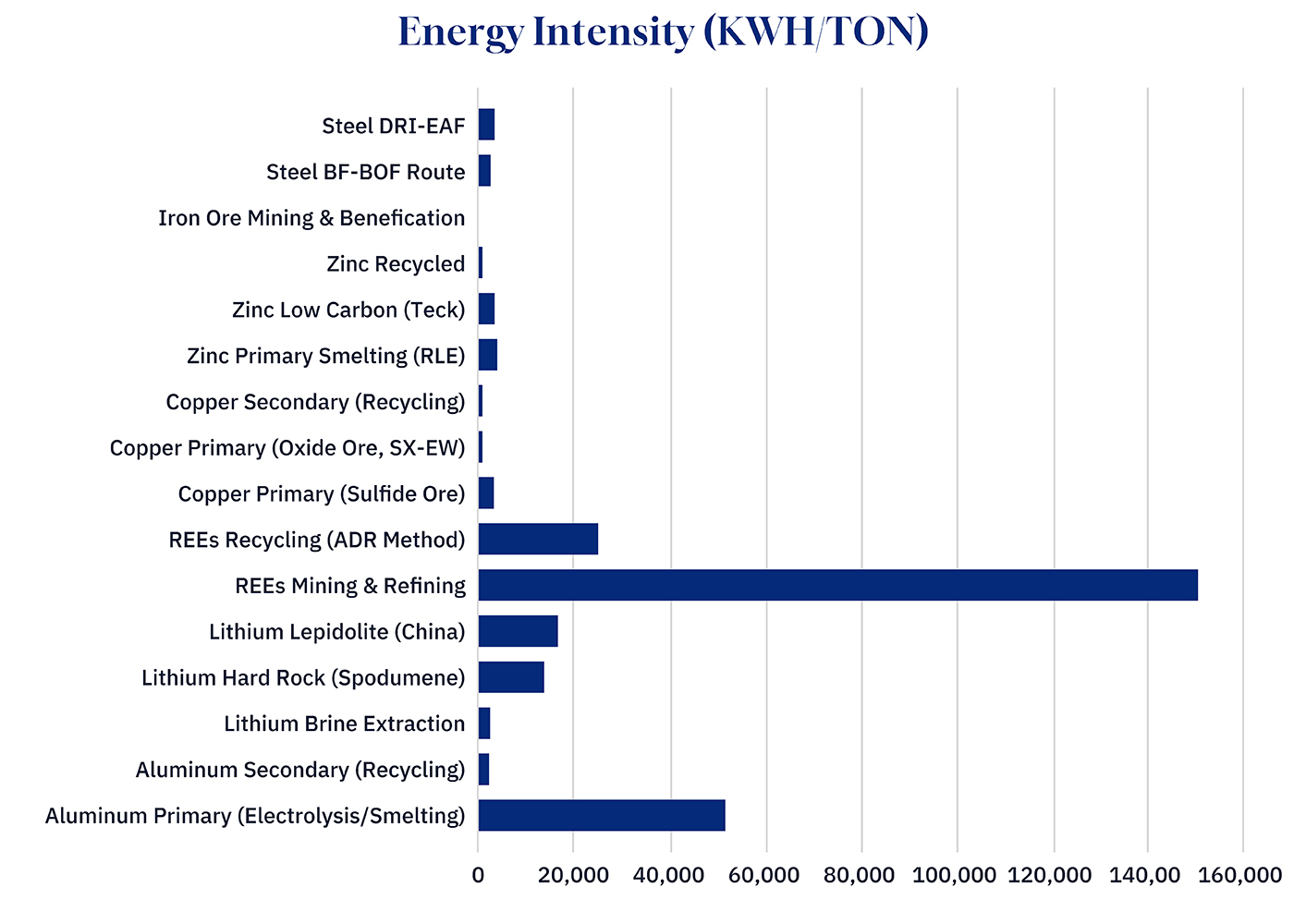

As shown in the charts below, aluminum and rare earth elements (REE) stand out as CO2 and energy-intensive processes where Canada’s low-cost, low-carbon energy—whether hydro, nuclear, renewables, plus batteries, or gas plus CCUS—should be a strategic advantage. Canada can also take further steps toward integrating its own provincial carbon markets and deepening integration with regional markets in the U.S., such as the Western Climate Initiative and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative in the northeast.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Canada’s resilience-oriented natural resources strategy should ultimately rest upon mutually reinforcing pillars. Prime Minister Mark Carney has called for Canada to be an energy superpower in both clean and conventional energy. But that call falls short both on specifics and breadth. Carney might instead position Canada as a natural resources superpower, fully embracing energy, minerals, and agriculture.

This strategy would take a cross-commodity approach by investing up and down the value chain from primary extraction to advanced manufacturing and by building on the integration points between resources.

- Critical minerals exploration, development, processing, and value-added manufacturing in transportation, steel, aluminum, electricity infrastructure, defence, and high-tech sectors

- Low-cost, baseload, clean electricity for AI/data centers and maintaining industrial competitiveness

- Oil, gas, and petrochemical development linking into export markets abroad and materials manufacturing at home

- Carbon management technologies, including hydrogen for industrial decarbonization, carbon capture and storage for power generation, and upstream methane abatement

- Uranium and nuclear fuel supply chains backstopping nuclear power, inclusive of minerals like zirconium, silver, and boron, that are essential for the construction and operation of reactors and nuclear fuel supply chains

- Fertilizer, processing, and bioenergy development strategies for the agriculture sector

Never has a comprehensive, fully national commitment to natural resource development been more urgently needed. Regional polarization and conflicting national narratives pitting one sector against another will leave Canada at the mercy not just of uncertain, potentially hostile policy from the U.S., but also ill-equipped to manage volatile and unpredictable global market conditions and shocks. By contrast, a national unity-oriented approach with a common policy signal will unlock capital and position Canada on the leaderboard for natural resources investment.

Steel coils cool at Algoma Steel Inc., in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., Friday, April 25, 2025. Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press.

A resilient industrial strategy for Canada

Natural resources is one main pillar of the Canadian economy, with manufacturing the other, though both are dwarfed by the services sector. Yet natural resources and manufacturing are also big drivers of the services sector, from housing to finance to education.

Carney enters office at a time when global industrial policy is undergoing a renaissance, albeit along an increasingly turbulent trajectory. The turbulence reflects a pivot away from green industrial policy focused on the energy transition that dominated the Trudeau government’s thinking, as well as in the Biden administration and in the EU.

Industrial policy is evolving rapidly toward a resilience-based framework. In this context, sector-level policy interventions in support of green industrial policy and electrification are increasingly secondary to national security and high-tech industries like semiconductors as the major drivers of policy for both critical minerals and industrial policy.

This shift is not just a Trump-driven phenomenon but has deeper roots in trends toward deglobalization, kinetic geopolitical conflicts, and growing state interventionism in the economy.

Canada has not adapted well to this environment from a policy perspective. Even on rare occasions where there is alignment on which sectors are strategic, follow-through is slow, below scale, and too often caught up in federal-provincial conflict. Industrial policy can easily become mired in regional economic development objectives, which have their own vital role, but should be viewed as a distinctive program.

Economic resilience is a much more elastic basis for industrial policy than a net-zero green strategy that must exclude greenhouse gas-intensive resources and sectors, or limit funding to programs that focus on decarbonization as opposed to other forms of innovation, or even levelling the playing field with global competitors benefiting from industrial subsidies.

The defence sector will be a priority area as part of an effort to meet higher NATO spending commitments and strengthen Arctic and border security through means such as helicopters, drones, icebreakers, and similar technology. The Canadian auto sector is also likely to be a priority sector in a resilience-based industrial policy, in part because of its vulnerability to U.S. trade action, its economic and political significance, and the fact that a range of facilities are in place to support Trudeau-era programs for EVs and batteries. Canada also has the critical minerals foundation, from aluminum and nickel to lithium and scandium, to support the legacy auto industry as well as emerging electric and hydrogen-powered technologies.

Many of the prominent public investments related to electric vehicles in Canada have been delayed or have collapsed outright. Yet Canada should continue to consider opportunities to find its place in the electrification of global transportation, particularly where it leverages critical minerals production. A more direct offtake link from battery and EV manufacturing could provide a vital source of capital.

Canada should look at where there are opportunities for alignment with the U.S. and other G7 partners on energy security, industrial supply chains, and the defence industrial base. While the Trump administration wants to manufacture at home first, its second choice is Canada and G7 partners, especially in strategic sectors where the competition—or in some cases, threat—is China.

The integration of critical minerals and energy into manufacturing underpins a resilience strategy, including sectors well beyond autos. The defence industrial base also starts with the resource base. The NATO/G7 frameworks could provide a leadership opportunity for Carney to reinvigorate the Minerals Security Partnership, with or without the U.S. The EU defence procurement strategy and reinvestment in the defence industrial base will provide an opportunity for Canadian critical minerals, including aluminum, nickel, titanium, zinc, and rare earths.

The high-tech sector relies on rare earths as well as China-dominated minerals such as gallium, germanium, and graphite. Establishing a price advantage on reliable, clean, and affordable energy will support energy-intensive minerals processing, which creates further downstream cost advantages for advanced manufacturing.

Previous proposals to support the Canadian critical minerals sector were primarily driven by the need to scale clean energy. In this way, critical minerals are viewed as a supply chain input for batteries, wind turbines, electric motors, electrolyzers, and solar panels. Many of the same financial incentives, derisking tools, and market reform structures proposed for low-carbon energy would also enable critical mineral development for sectors such as defence and high-tech.

The new EU Clean Industrial Deal embraces critical minerals in this way, as part of a strategy that seeks to combine a competitive, resilience-oriented response with the ongoing commitment to a stronger industrial base for clean energy. The EU plan acknowledges the continent’s “limited resources,” highlighting both the need to embrace circularity and recycling in its critical minerals strategy and the need to ensure that European industry is “secure and resilient in the face of global competition and geopolitical uncertainties.”

Ore is hauled from the Kennecott’s Bingham Canyon Copper Mine Wednesday, May 11, 2022, in Herriman, Utah. Rick Bowmer/AP Photo.

Prime Minister Carney is likely to pursue an industrial strategy for critical minerals that seeks to offer a supply solution to the EU while mirroring its balanced approach between a continued focus on low-carbon energy and key supply chains around defence and high-tech manufacturing. The government will have to navigate proposed “Buy EU” criteria that could limit opportunities for Canada, although this is less likely in raw materials than in manufactured clean energy products.

The Carney government’s proposal for a “First and Last Mile” Fund (FLMF) provides an attractive vehicle for critical minerals. It will likewise retain and/or expand Trudeau-era programs such as the Canada Growth Fund, the Canada Infrastructure Bank, indigenous loan guarantees, and the Strategic Innovation Fund. These investment programs, alongside expansion of investment tax credits, are well-suited to support a resilience-based industrial policy strategy.

The FLMF proposal reflects the realization that these other Trudeau-era programs were not fit-for-purpose when it came to the mining sector. This industry has a diverse array of financing needs, from small-scale exploration and early-stage technological innovation to multibillion-dollar mine and smelter development. The first mile (exploration) and the last mile (processing/value-add) have particularly high-risk profiles that limit the available pool of investors and drive up hurdle rates and cost of capital.

Clean energy will remain on the table. Carney will look to align with elements of the EU Green Industrial Deal, particularly around critical minerals and GHG-intensive materials such as steel, aluminum, cement, and fertilizer, which will fall under a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The government campaigned on a Canadian CBAM, which could align with the EU program, given that Canada and the EU have carbon pricing equivalency.

Other clean energy sectors, such as hydrogen and wind, may be viewed as not sufficiently strategic or impactful as pathways for building resilience against the U.S. challenge. Meanwhile, sectors such as nuclear and LNG may offer greater return on investment for taxpayer dollars from a resilience and nation-building perspective. Nuclear and LNG are sectors that offer leverage not just with the U.S., but with target diversification markets in the EU and Asia as well.

Japan has its own Green Transformation (GX) industrial plan that will probably align with both the EU and Canada, although its approach to carbon pricing and carbon border adjustment is much more iterative. Japan’s downstream energy and minerals sector represents significant partnership potential for Canada through government investments available through agencies such as Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC).

Conclusion

International alliances, market diversification, and public-private partnerships will all play a vital role in constructing a new natural resources strategy and resilience-oriented industrial policy for Canada to unlock the potential of sectors such as critical minerals. Yet clearly, a much broader suite of policy tools must also be deployed to strengthen Canadian economic resilience. These include areas such as tax reform, infrastructure investment, support for R&D and skills development, immigration policy for entrepreneurs and investors, and removal of interprovincial trade barriers.

The question of regulatory reform to fast-track resource development in Canada looms above all other policy questions for the natural resources sector. Prime Minister Carney appears poised to distance himself from the climate-heavy regulatory agenda of the Trudeau government and promises a faster, more efficient process for energy, mining, and infrastructure projects that promises project decisions in no more than two years.

It’s important to note that the process of reform in Canada is taking place at the same time as Republican leaders in Washington are pledging deregulation to benefit natural resources projects, especially in the mining industry, through new laws and executive actions. There’s considerable uncertainty around these efforts, however, including the risk of failure for the U.S., which could put Canada into a stronger, competitive positioning by comparison. Congress has already failed twice in three years at prior bipartisan reform efforts.

If Canada can tighten timelines for assessments and permitting without overreaching, as the Trump administration may risk doing, it could become a more stable draw for investment in North America. It’s critical, too, that these reforms in Canada do not reverse hard-won gains on Indigenous consultation, which could return Canada to a higher-risk business climate with a greater probability of social and legal conflict with First Nations.

These policy areas can be important on their own, but would be most effective as part of an integrated, top-down strategic framework. The Trudeau government tried to use this approach to align regulation, subsidies, carbon pricing, and legislation to backstop its green industrial/low-carbon economy plans. The same spirit of ambition and broad coordination could be applied to an industrial strategy with the goal of economic resiliency. Close coordination with provinces, First Nations, business, capital providers, labour, and environmental groups will be essential to create stronger alignment and lessen execution risk.

This DeepDive was made possible by Rio Tinto and the generosity of readers like you. Donate today.