Over the past few decades, women in Canada have made major economic gains. More are going to university, entering the workforce, and earning higher incomes.

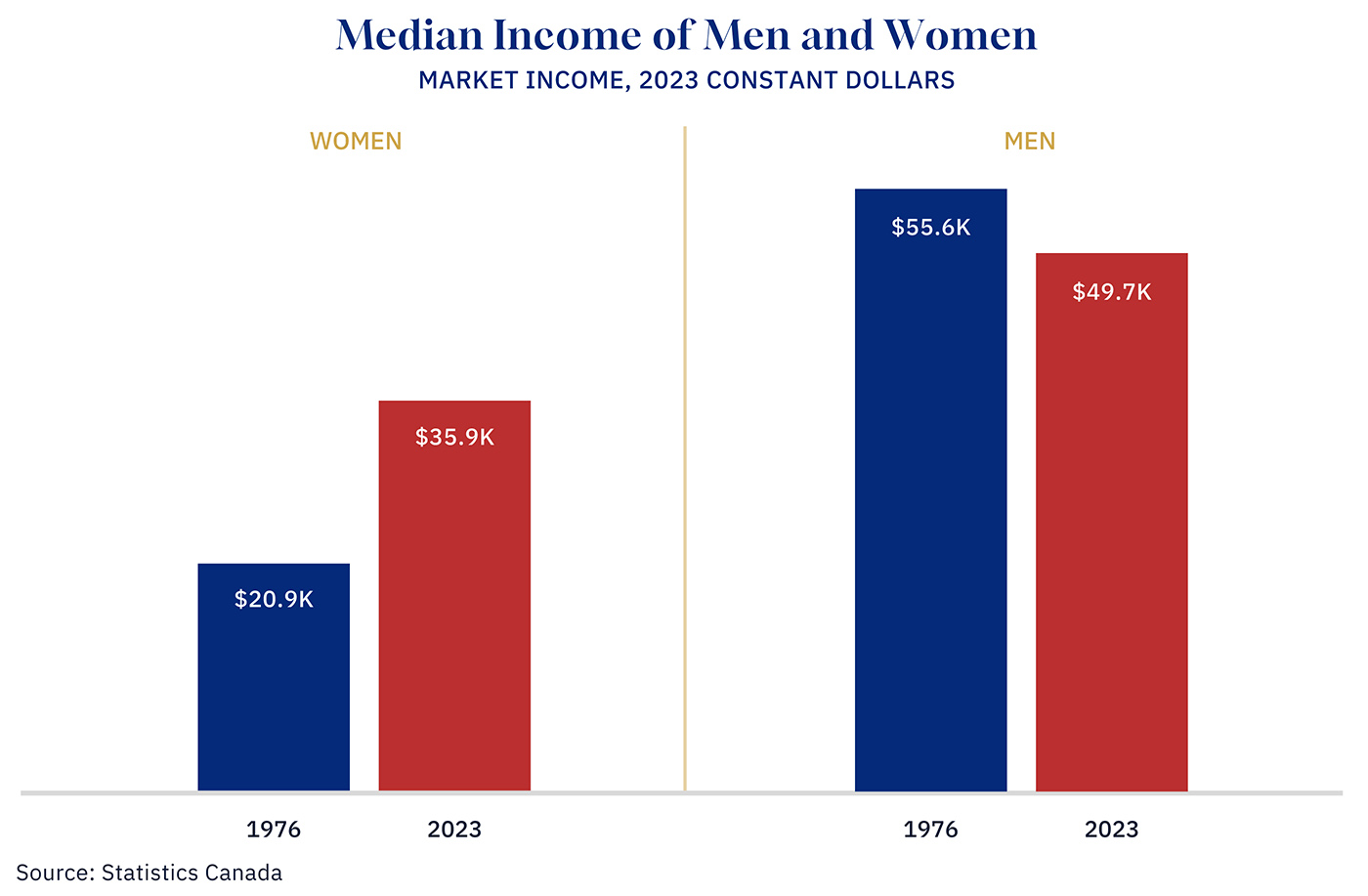

Also encouraging: the gender wage gap has narrowed significantly. Back in 1976—the first year with available data—women earned just 38 percent of what men made (based on median earnings before any taxes or government support). By 2023, that number had risen to about 72 percent.

Of course, the fact that a gap still exists is a problem. And one of the biggest—and most complicated—reasons it persists isn’t job choice or outright bias. It’s what researchers call the “child penalty.” After people have kids, men’s and women’s earnings diverge—a trend seen in other rich countries.

Still, the progress made is pretty incredible—and worth celebrating.

But there’s a “but.” If you take a closer look at the wage gap, you’ll see the narrowing gap isn’t just because women are earning more. It’s also because men’s earnings have stagnated.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson.

Since 1976, median income for women has grown by about 1 percent per year. Over the same period, men’s earnings have actually fallen by around 0.2 percent annually. In today’s dollars, women are making about $15,000 more than they were nearly 50 years ago, while men are making about $6,000 less.

Why men haven’t seen any improvement isn’t entirely clear, but there are some likely explanations. One is the loss of high-paying manufacturing jobs traditionally held by men. As automation and globalization reshaped the industry, the share of men working in manufacturing fell by half—from 23 percent to 11 percent. Meanwhile, the jobs that remain tend to pay less than they used to. An increase in high-paying resource jobs may have provided a temporary cushion, but those, too, have declined with the oil price collapse in the mid-2010s.

Education is another part of the story. Compared with young women, men are less likely to pursue higher education, which is increasingly essential to access high-paying jobs. For decades, men had the edge in university education, but that flipped in 2011. Now, women are more likely to hold university degrees than men.

More concerning still, young men are less likely than young women to be doing anything at all to set themselves up for financial success. About 12 percent of young men aged 20 to 29 are not in employment, education, or training—a group referred to as NEET. While overall NEET rates have declined since the late 1990s, the gender gap has reversed, with young men now more likely to fall into this category. That’s likely to weigh on future earnings.

Canada should keep working to close the gender gap in earnings, especially after parenthood. But it can’t afford to ignore how men are doing, too. The fact that men’s earnings have been stagnant for decades is a serious concern.

If income growth stays weak and young men continue to fall behind in education and work, they’re likely to see lower lifetime earnings. That’s more than a financial problem; it could mean a growing disconnection from work and society, mental health struggles, and even social unrest. That’s not just bad news for men—it’s bad for everyone.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.