When the intersection of law and technology presents seemingly intractable new challenges, policymakers often bet on technology itself to solve the problem. Whether countering copyright infringement with digital locks, limiting access to unregulated services with website blocking, or deploying artificial intelligence to facilitate content moderation, there is a recurring hope that the answer to the policy dilemma lies in better technology.

While technology frequently does play a role, experience suggests that the reality is far more complicated, as new technologies also create new risks and bring unforeseen consequences. So too with the emphasis on age verification technologies as a magical solution to limiting underage access to adult content online. These technologies offer some promise, but the significant privacy and accuracy risks that could inhibit freedom of expression are too great to ignore.

The Canadian debate over age verification technologies, which has now expanded to include both age verification and age estimation systems, requires an assessment of both the proposed legislative frameworks and the technologies themselves. The last Parliament featured debate over several contentious internet-related bills, notably streaming and news laws (Bills C-11 and C-18), online harms (Bill C-63), and internet age verification and website blocking (Bill S-210). Bill S-210 fell below the radar screen for many months as it started in the Senate and received only a cursory review in the House of Commons. The bill faced only a final vote in the House, but it died with the election call. Once Parliament resumed, the bill’s sponsor, Senator Julie Miville-Dechêne, wasted no time in bringing it back as Bill S-209.

The bill would create an offence for any organization making available pornographic material to anyone under the age of 18 for commercial purposes. The penalty for doing so is $250,000 for the first offence and up to $500,000 for any subsequent offences. Organizations can rely on three potential defences:

- The organization instituted a government-approved “prescribed age verification or age estimation method” to limit access. There is a major global business of vendors that sell these technologies and who are vocal proponents of this kind of legislation.

- The organization can make the case that there is “legitimate purpose related to science, medicine, education or the arts.”

- The organization took steps required to limit access after having received a notification from the enforcement agency (likely the CRTC).

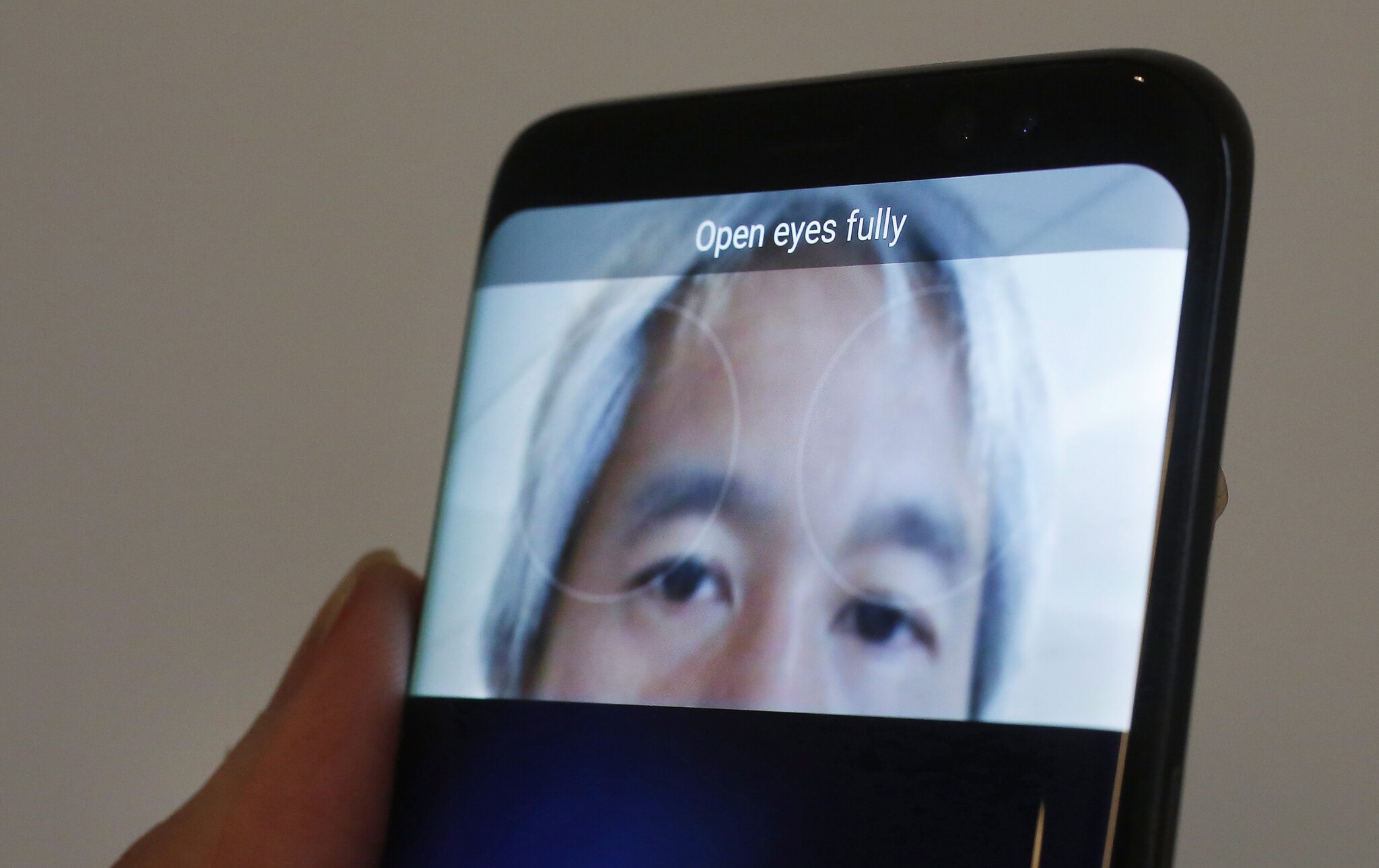

Note that Bill S-209 has expanded the scope of available technologies for implementation: while S-210 only included age verification, S-209 adds age estimation technologies, which estimate a person’s age from a photo. Age estimation may benefit from limiting the amount of data that needs to be collected from an individual, but it also suffers from inaccuracies. For example, using estimation to distinguish between a 17-year-old and an 18-year-old is difficult for both humans and computers, yet the law depends on it.The government would determine through regulation what constitutes valid age verification or age estimation technologies. In doing so, the bill says it must ensure that the method: (a) is highly effective; (b) is operated by a third-party organization that deals at arm’s length from any organization making pornographic material available on the Internet for commercial purposes; (c) maintains user privacy and protects user personal information; (d) collects and uses personal information solely for age-verification or age-estimation purposes, except to the extent required by law; (e) limits the collection of personal information to what is strictly necessary for the age verification or age estimation; (f) destroys any personal information collected for age-verification or age-estimation purposes once the verification or estimation is completed; and (g) generally complies with best practices in the fields of age verification and age estimation, as well as privacy protection. This list is more expansive than the previous bill, and it states that the government must ensure that it meets these requirements, not merely consider them. The list notably limits the technology providers to third parties, meaning that the sites themselves cannot operate the age verification system. It also requires the system to be “highly effective,” while the previous bill only required reliability. As noted, age estimation may struggle to meet these standards.