It’s like tariff déjà vu: once again, the U.S. is threatening Canada with new tariffs. And, once again, policymakers are faced with big questions: what could Canada offer to avoid them? Should it even try?

The federal government has already backed off its proposed digital services tax, which would have mostly hit big U.S. tech firms like Google and Amazon. And instead of a bargaining chip to gain concessions, Canada was rewarded with a new tariff threat. Now, the next, and most obvious, bargaining chip is Canada’s supply-managed dairy industry—something the president has repeatedly blasted as ripping off American farmers.

While similar accusations were made about the digital services tax, the prime minister has asserted that changes to supply management are a hard no in negotiations with the U.S. At the moment, that seems unlikely to change given both the issue’s political sensitivity and the fact that there’s now legislation on the books essentially stating as much: the minister of foreign affairs is prohibited from using supply management as leverage in negotiations.

As a quick primer, supply management basically works like this: marketing boards limit how much dairy (and poultry) is produced in Canada so that they can control the prices we all pay. But that only works if foreign competition is restricted. Otherwise, Canadians would likely forego domestic products and instead buy cheaper imports. That’s why most dairy and poultry imports into Canada can potentially face tariffs of at least 200 percent.

It’s worth noting that supply management hasn’t always been completely off the table in trade talks. In response to pressure from trading partners in recent years, the government has allowed a small but growing amount of foreign dairy to enter Canada before those high tariffs kick in—something known as a “tariff rate quota.” These quota increases were made under both the 2017 trade agreement with the E.U. and the 2020 CUSMA agreement with the U.S.

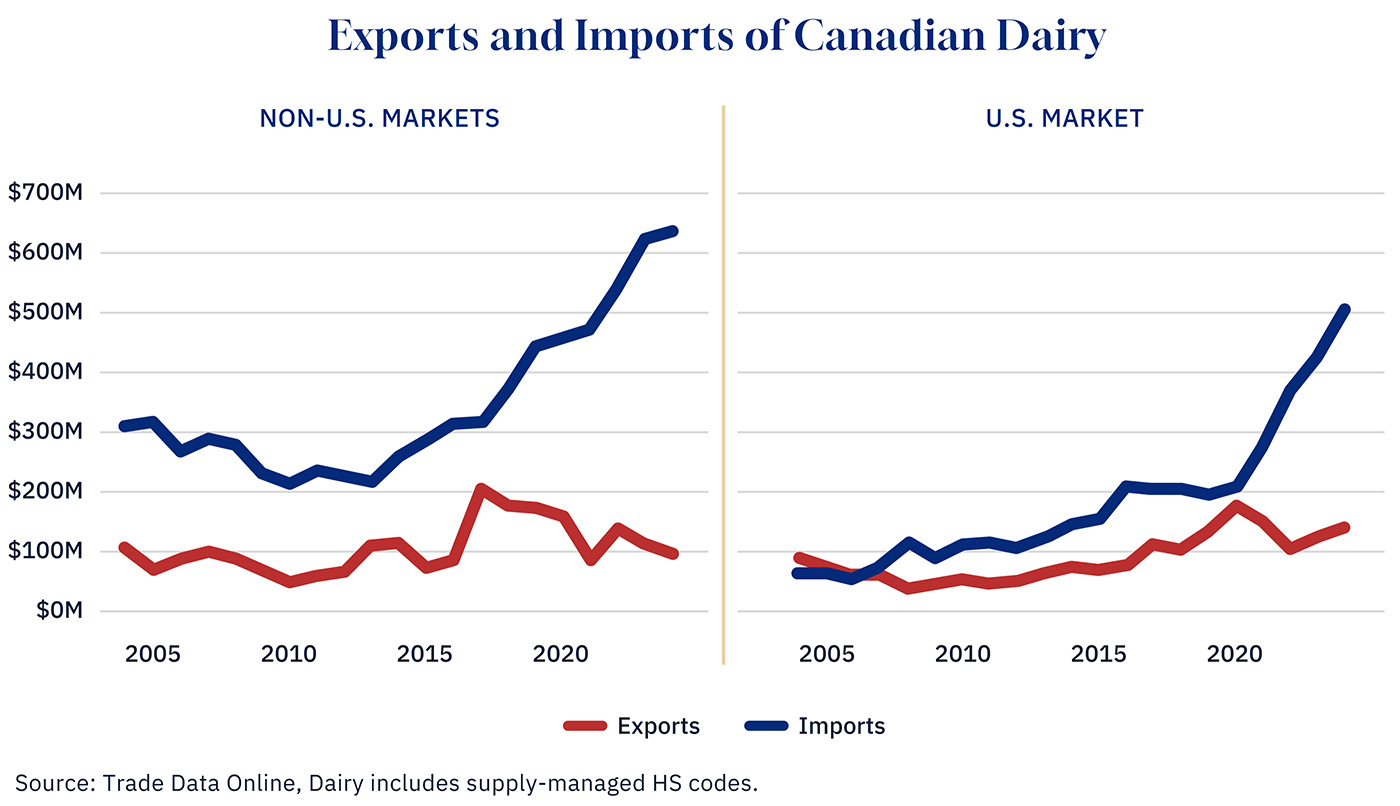

As a result, Canadians now purchase more foreign dairy than ever before. And, since supply-managed industries don’t prioritize the export market, we import more dairy from other countries than we export to them, especially with the U.S. But, when it comes to the U.S., there’s also more at play.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The U.S. is no free-market angel either. Though they don’t manage the supply of the industry, they still very much support and protect dairy farmers through large subsidies and their own system of similarly high tariffs beyond quota limits. Together, these factors lower the cost of American dairy stateside and price Canadian and other foreign dairy out of the market.

In the end, neither country may be playing entirely fairly. Regardless, Canada could view expanded access to foreign dairy not as a concession to the U.S., but as a benefit for Canadian consumers who pay higher prices for essentials like milk and butter.

A version of this post was originally published by the Business Council of Alberta at businesscouncilab.com.