DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners. The DeepDives series is made possible thanks to the ongoing support of the Centre for Civic Engagement.

Canada is a high-trust country. Surveys consistently show that Canadians are more likely than most people in the world to say “others can be trusted,” to respect the rules, and to view government and civic institutions as broadly legitimate. In Q4 2024, for instance, 43.5 percent of Canadians reported that “most people can be trusted”, which is significantly higher than global averages and among the highest in the OECD.

This sense of collective trust is a huge advantage for the country. It helps to explain why our markets function as well as they do, why our democracy is relatively stable, and why Canada is generally seen as a good place to live and invest.

Scholars often note that only a small cluster of countries consistently report that a majority of people can be trusted. That makes Canada an outlier in the global context. Preserving that advantage has, among other benefits, major economic upside. Economic research, for instance, links a one-point rise in generalized trust to several percentage points of GDP per capita in the long run.

Trust isn’t a static inheritance. It’s continually shaped by social change, economic developments, and political choices. Immigration, in particular, has long interacted with these trust dynamics—sometimes straining them but more often reinforcing them. For decades, newcomers have contributed to Canada’s economy, enriched its culture, and, over time, come to share in its high-trust norms.

But the unprecedented scale of today’s immigration experiment raises new questions that haven’t yet been squarely addressed by policymakers or commentators.

The central issue is this: What happens when a high-trust society welcomes large numbers of newcomers from countries with lower levels of trust? Do newcomers converge toward Canada’s institutions and norms of cooperation, or does the sheer scale of change begin to alter those norms themselves?

In the past, the answer has generally been positive. Over generations, immigrants and their children have converged toward Canadian levels of trust. Yet scale, speed, and segregation matter. When half the population in some of our cities is already foreign-born, and when housing and settlement patterns reduce day-to-day mixing, can we still assume the same outcome?

This DeepDive essay aims to explore that question by surveying the best theoretical and empirical research on the relationship between immigration, diversity, and social trust. The research shows that high-trust societies can remain resilient, but only if their institutions function well and integration is actively managed. Canada’s unprecedented immigration levels make those conditions harder to sustain.

A Canada Day parade in Montreal, July 1, 2023. Graham Hughes/The Canadian Press.

Defining and measuring trust

Before surveying the theories about trust, it’s worth clarifying what social scientists mean by the term, how they measure it, and where Canada stands in comparative perspective.

Most of the research distinguishes between two kinds of trust: particularized trust and generalized trust. Particularized trust refers to confidence in people you know—family, friends, neighbours, and members of your own group. Generalized trust refers to confidence in people you don’t know—strangers, people outside your ethnic or social circle, the proverbial “someone on the street.” It’s this second form of trust that matters most for how societies function. High levels of generalized trust make it easier to cooperate with others, form civic associations, build large companies, and sustain effective government institutions.

Measuring trust may sound difficult, but the dominant tool is surprisingly simple. For decades, surveys like the World Values Survey and the OECD’s trust surveys have relied on a straightforward question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” The share of respondents who choose the first option is taken as a proxy for the level of generalized trust in a society.

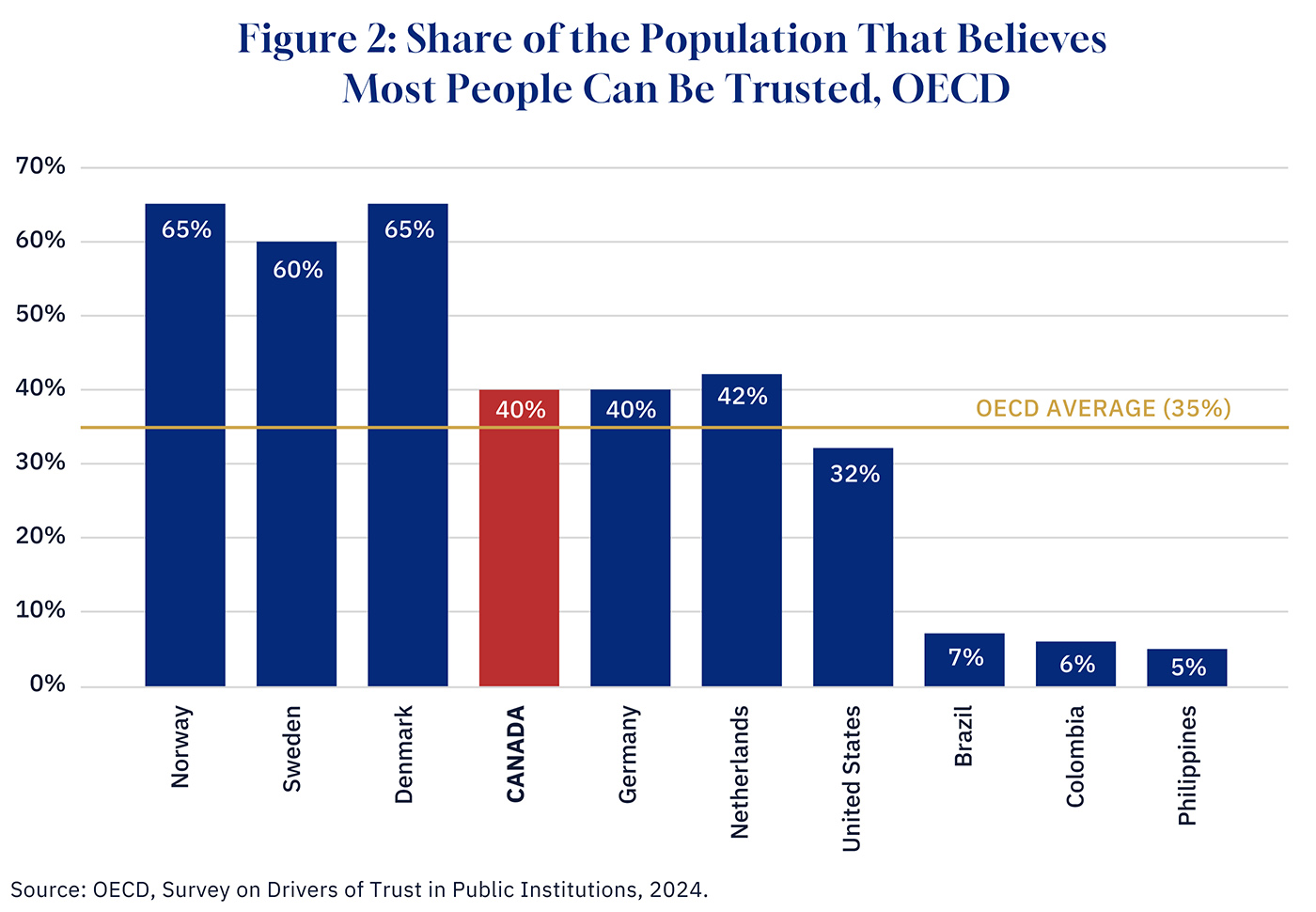

The results show wide variation across countries. The highest-trust societies are typically in Northern Europe. In Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, for instance, more than 60 percent of respondents say that most people can be trusted. At the other end of the spectrum, in countries like Brazil, Colombia, and the Philippines, the share can be as low as 5 percent. The United States falls somewhere in the middle, with roughly a third of respondents expressing generalized trust.

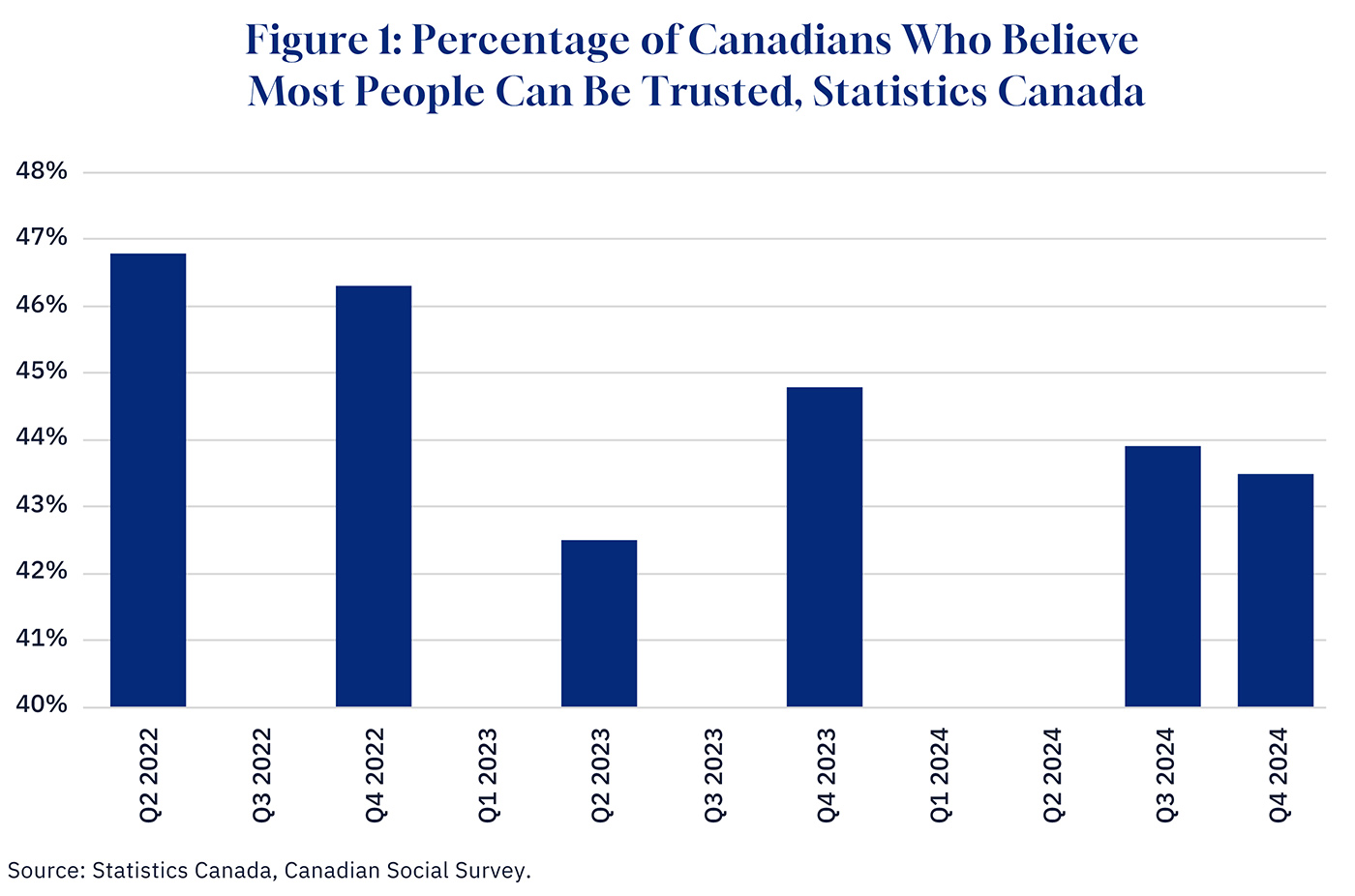

Canada consistently ranks as a high-trust country. Roughly 40 percent of Canadians tell survey researchers that most people can be trusted—though the number has been falling in recent years. According to Statistics Canada’s Canadian Social Survey, for instance, the share of Canadians who believe that most people can be trusted has fallen from 46.8 percent in Q2 2022 to 43.5 percent in Q4 2024 (see figure 1).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The downward drift in Canadian trust levels may seem small, but longitudinal research shows that even modest declines can signal important shifts. A fall from the mid-40s to the low-40s is equivalent to millions fewer Canadians who would say that strangers can be trusted. By comparison, trust levels in the United States have fallen from over 50 percent in the 1960s to the low 30s today. Canada’s trajectory isn’t nearly as steep, but the direction is worrisome.

Canadians’ trust levels are nevertheless still higher than the OECD average and comparable to Germany or the Netherlands (see Figure 2). The picture that emerges is of Canada as a relatively high-trust society, but one where trust levels show signs of softening. That makes it all the more important to understand what sustains generalized trust, and what might threaten it, before turning to the role of immigration and diversity.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Why does trust matter?

High levels of social trust are rightly seen as a civic and engagement advantage. Scholars have shown that trust acts as a source of social capital that lowers transaction costs, facilitates cooperation, and enables societies to organize at scale. High-trust societies can build dynamic economies and robust democracies. Low-trust societies often rely on family ties, informal networks, or heavy state coercion.

Studies estimate that differences in trust can explain up to one-fifth of the variance in economic growth across advanced countries. Trust lowers the cost of credit, increases investment horizons, and reduces reliance on costly monitoring. In low-trust societies, firms tend to remain family-owned and small; in high-trust ones, large corporations can emerge because strangers are more willing to collaborate.

Political theorist Francis Fukuyama’s 1995 book, Trust, remains one of the most influential accounts of how cultural norms shape economic and political outcomes. He distinguished between high-trust societies such as the United States, Germany, and Japan, and low-trust ones such as China, France, and Italy.

The distinction wasn’t merely descriptive but analytic: in high-trust contexts, people are able to cooperate beyond kinship networks, which in turn enables the rise of large-scale firms, vibrant civic associations, and credible political institutions. In low-trust societies, by contrast, confidence rarely extends beyond the family, constraining organizational scale and leaving more functions to the state. For Fukuyama, generalized trust is a cultural inheritance that’s transmitted across generations and rooted in historical experience.

Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam offered a complementary perspective in his landmark study, Bowling Alone, published in 2000. Where Fukuyama emphasized cultural inheritance, Putnam focused on the observable decline of “social capital” in the United States. He documented the ways in which Americans were disengaging from civic groups, community associations, and even informal networks, and how that erosion of associational life was mirrored by declining interpersonal trust.

In a subsequent essay, E Pluribus Unum, Putnam addressed the role of diversity more directly. His large-N empirical work showed that more ethnically diverse communities often reported lower levels of trust—not only between groups, but even within them. He described this response as people “hunkering down.” Yet Putnam was careful to stress that this outcome wasn’t inevitable. In his view, the long-term trajectory could still be one of rising trust if institutions fostered integration and common identities. The critical variables were the scale and speed of demographic change, and the strength of institutions tasked with absorbing it.

Political scientist Eric Uslaner advanced the debate by shifting attention from observable networks to moral orientation in his 2002 book, The Moral Foundations of Trust. For Uslaner, generalized trust isn’t simply a reflection of civic participation or rational calculation, but an ingrained belief that society is fair and the future is hopeful. In this sense, trust functions almost like an ethical disposition: it’s passed down across generations and thus proves remarkably “sticky.”

Yet, once eroded, it’s extraordinarily difficult to rebuild. This perspective helps to explain why some societies remain stably high-trust across centuries, while others persist in low-trust equilibria despite sustained economic growth or democratization. Uslaner’s account reminds us that generalized trust isn’t only fragile but also path-dependent, shaped by historical experience and cultural transmission as much as by contemporary conditions.

People carry Chinese and Canadian flags while marching in the Chinese New Year Parade in Vancouver on Sunday, Feb. 10, 2019. Darryl Dyck/The Canadian Press.

Other scholars have drawn a distinction between “bonding” and “bridging” forms of social capital. Bonding refers to the ties within homogeneous groups such as families, ethnic networks, or religious communities. Bridging refers to ties that cut across lines of race, class, or religion.

Both forms matter, but generalized trust ultimately depends on bridging. Immigration, for example, can either expand bridging trust if managed well or reinforce bonding trust in ethnic enclaves if managed poorly. The difference hinges on whether newcomers are successfully integrated into broader networks and institutions, or whether they remain confined to narrower circles of solidarity.

Institutions themselves also play a decisive role in shaping trust. Fair courts, effective public services, and predictable laws reinforce generalized trust, while weak or corrupt institutions corrode it. Immigration interacts with this institutional dynamic. Large inflows of newcomers from low-trust societies are less risky if public systems—health care, housing, education, justice—are resilient enough to absorb the additional demands. If they falter under pressure, the risks to social trust rise accordingly. Strong institutions can, in effect, serve as bridges; weak ones can deepen fragmentation.

Trust also underpins democratic resilience. Research shows that when citizens lose confidence in one another and in institutions, they become more susceptible to populist appeals, conspiracy theories, and polarization. In this sense, Canada’s high-trust inheritance has acted as a shock absorber against global currents of populism.

Taken together, this body of theoretical literature leaves us with two central lessons. First, trust is both a cultural and institutional inheritance that underpins prosperity and democracy. Second, it can erode under pressure from fragmentation, rapid demographic change, or weak governance. The question for Canada is whether today’s immigration scale risks crossing that threshold.

What do we know about immigration and social trust?

The empirical record on immigration, diversity, and trust is mixed—but not meaningless. It highlights both the risks and the resilience of high-trust societies.

Canada

Canadian scholars note that our immigration and settlement policies have served as institutional buffers. Yet these studies often drew on periods when annual immigration was in the range of 200,000 to 300,000. Today’s levels are several times higher, and the evidence base for what happens at this unprecedented scale is thin.

Canada has long been a case study in successful immigration. Research has found that while ethnic diversity can reduce neighborhood-level trust, strong national institutions and redistributive policies mitigate the effect. Other Canadian studies likewise find that the diversity–trust effect is strongest at the micro level (e.g., neighbourhoods) but tends to dissipate at larger scales where institutions and national identity buffer it. World Values Survey data shows second-generation immigrants often converge toward Canadian levels of generalized trust. This convergence has historically underpinned Canada’s reputation as a multicultural success.

But scale is a new variable. Immigration levels today are unprecedented. In some metropolitan areas, more than half of residents are foreign-born. In 2021, nearly 47 percent of Toronto’s CMA residents were foreign-born, and several GTA municipalities—Markham, Richmond Hill, Mississauga, Brampton—are now majority-immigrant. Vancouver is at about 42 percent. Rising housing costs, long health-care wait times, and crowded transit raise the risk that institutions may no longer deliver the same integrative outcomes. There is, in short, less margin for error.

United States

The U.S. offers a mixed picture. Putnam’s findings showed diversity initially lowered trust—people withdrew not just from “others” but even from their own group. This “hunkering down” effect is well-documented: diversity can dampen associational life in the short term. Follow-up research has shown that while immigrants themselves tend to exhibit lower initial levels of generalized trust, their children’s trust levels generally converge upward. This suggests that integration is real, but the process can take decades. The short-term dip is real, and can therefore complicate politics in times of rapid demographic change.

In this photo from Tuesday, May 1, 2007, protesters are seen through an American flag as they rally to support immigration reform in Las Vegas. Jae C. Hong/AP Photo.

Europe

Europe, especially Scandinavia, has been a laboratory for studying trust under immigration pressure. Denmark, Sweden, and Norway are historically the highest-trust societies in the world.

Yet research shows immigration has modestly lowered generalized trust, particularly where migrants cluster in segregated neighbourhoods. Swedish studies find that negatives tend to weigh more heavily than positives in diverse neighbourhoods, and the effects are strongest when segregation and socio-economic disadvantage overlap. Germany’s experience with Turkish “guest workers” illustrates how weak integration policies can entrench bonding trust within enclaves, which in turn slows convergence.

In Scandinavia, where trust has historically exceeded 60 percent, even small declines are taken seriously. Danish and Swedish policymakers debate immigration in explicitly trust-related terms, reflecting an awareness that their high-trust inheritance is both precious and fragile.

Cross-county evidence

Cross-country studies add nuance. A 2020 meta-analysis found that while ethnic diversity often correlates with lower trust, effect sizes are small to moderate and heavily context-dependent. Where institutions are strong, education is high, and integration policies are robust, trust recovers. Where those conditions are absent, the negative effects are more persistent.

One of the most striking findings from cross-national reviews is that perceived diversity can matter as much as objective diversity. If citizens believe that neighbourhoods are becoming less cohesive—even if the actual demographic change is modest—trust can erode. That helps explain why the politics of immigration often intensify ahead of the underlying demographic realities.

Intergenerational convergence is another consistent finding: children of immigrants across Europe and North America tend to approach host-country trust levels, though the pace and completeness of convergence vary.

Lessons

The empirical literature suggests three takeaways. First, immigration can lower trust in the short run, especially at the neighbourhood level. Second, over time and across generations, convergence is possible, but it’s not automatic. Repeated, structured contact across groups—through schools, public services, or civic programs—consistently improves outcomes. The policy lever isn’t diversity itself but how it is managed in daily life. Third, scale and speed matter. Smaller, gradual inflows are easier to integrate; rapid, large-scale inflows can overwhelm institutions and delay trust-building.

Canada’s past experience has been largely positive, but past performance doesn’t guarantee future results. The unprecedented scale and pace of today’s immigration experiment test these findings.

Canada’s current immigration experiment

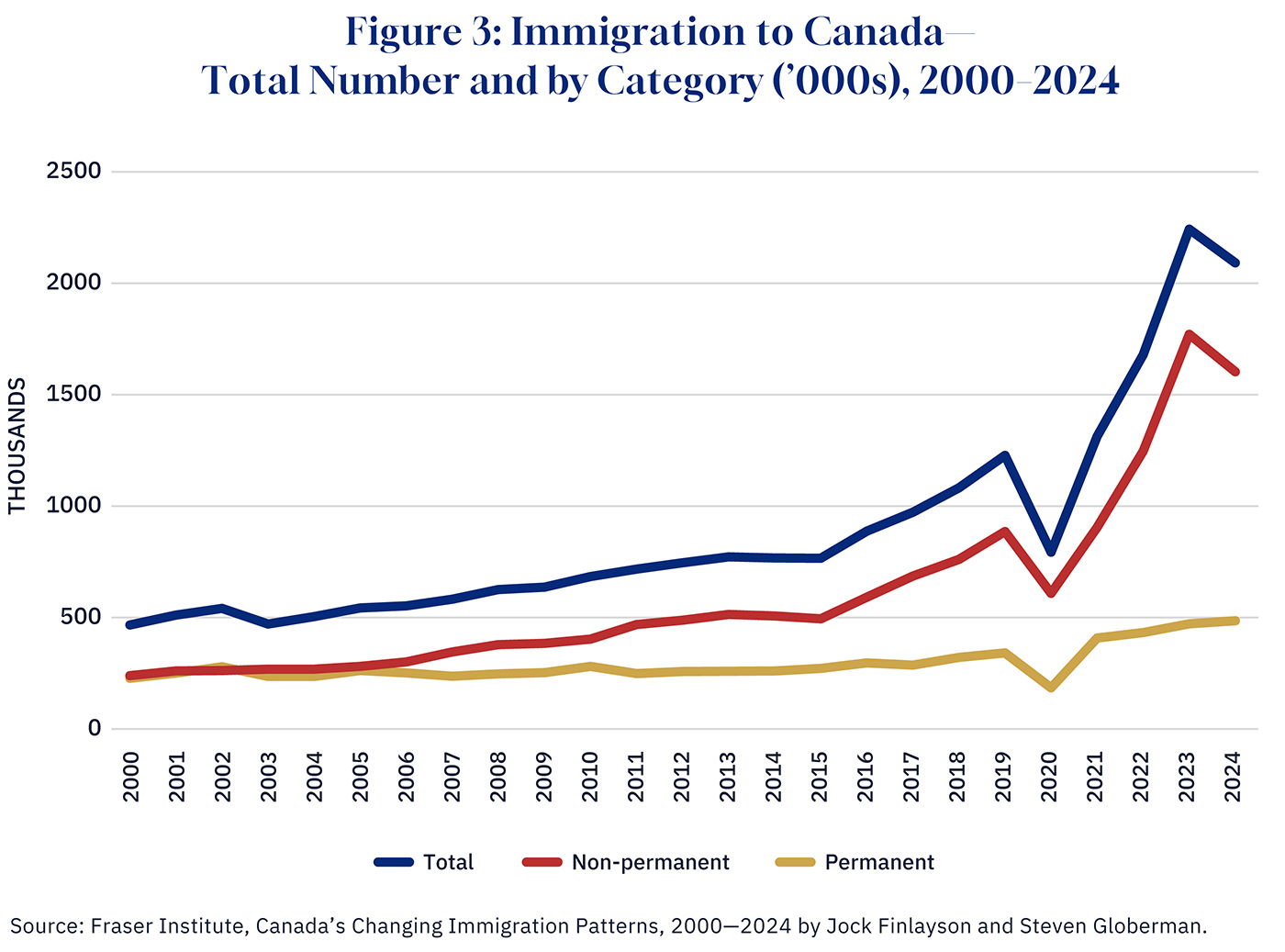

Immigration has always been central to Canada’s national story. But today’s scale is unprecedented. Annual inflows of newcomers—including permanent and temporary residents—surpassed 1.2 million in 2023 and roughly three-quarters of a million in 2024. That represents population growth of nearly 3 percent in 2023—the fastest in 66 years and among the highest rates in the world. For perspective, it’s the equivalent of adding a city the size of Calgary every 12 months.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The speed and scale of immigration are unprecedented. It’s fundamentally different from past experiences. In earlier decades, immigration was significant but gradual, which gave time for convergence in trust, culture, and civic identity. Today’s scale compresses those timelines and strains the capacity of institutions to mediate the process.

It’s also far more highly geographically concentrated than historic patterns. More than 90 percent of newcomers settle in just four provinces—Ontario, British Columbia, Quebec, and Alberta—and within them, overwhelmingly in a handful of large metropolitan areas. In Toronto, Vancouver, Calgary, and Montreal, the scale of immigration is transforming the cities’ demography and putting pressure on housing, infrastructure, and social services.

Housing is the best-known example. A supply-constrained housing market is absorbing record demand from newcomers, which in turn has pushed affordability to historic lows. But growing evidence from other parts of civic life is notable too.

The Hub recently published an analysis, for instance, that showed in some of the country’s largest school districts, a third or more of students spoke neither English nor French. The school system is a bellwether. When more than 30 percent of students speak another language at home, the classroom becomes a primary site of integration. If schools succeed, they can generate bridging trust. Yet if they struggle, they risk entrenching divides.

These bottlenecks matter for trust because effective institutions are the mechanisms through which integration takes place. When institutions falter, both newcomers and existing citizens may lose confidence in them—and, by extension, in each other.

Spatial segregation compounds the problem. Rising housing costs have pushed newcomers into concentrated enclaves. The 2021 Census showed that 46.6 percent of residents in the Greater Toronto Area were immigrants, and municipalities like Markham (58.6 percent), Richmond Hill (58.2 percent), Mississauga (53.2 percent), and Brampton (52.9 percent) are now among the most immigrant-concentrated in Canada. Over time, the clustering trend has accelerated: in the early 2000s, visible minority shares in Mississauga rose from 40.3 percent (2001) to 53.7 percent (2011), and in Brampton from 40.2 percent to 66.4 percent, which points to intensifying ethnic concentration in suburban areas.

Economists note that segregation can produce “tipping points”: once a neighbourhood crosses a certain threshold of linguistic or cultural concentration, the likelihood of further out-migration by majority residents increases. That dynamic, documented in U.S. and European cities, may already be unfolding in parts of the GTA and Metro Vancouver.

This matters because segregation slows the development of bridging trust and increases reliance on bonding trust within communities. The long-run risk is that instead of convergence toward Canadian norms, we see the persistence of parallel yet separate societies.

None of this is inevitable. But it raises legitimate questions. Can Canada’s institutions, which once successfully integrated large numbers of newcomers, sustain that role under today’s conditions? Or does scale itself alter the dynamics of trust in ways that make past performance less predictive?

Key takeaways

Canada’s high-trust inheritance is a huge advantage. It underpins prosperity, democratic stability, and a culture of cooperation that distinguishes Canada in a fractious world.

Immigration has historically fit within this inheritance: newcomers and their children have converged toward Canadian levels of generalized trust, reinforcing rather than eroding the country’s social fabric.

But the present moment is fundamentally different. The combination of unprecedented scale, compressed timelines, and geographic concentration raises the possibility that past patterns of convergence may no longer hold. Annual inflows have recently exceeded one million newcomers, most settling in a handful of metropolitan regions already grappling with housing shortages, strained schools, and other overburdened services. These pressures, in turn, heighten the risk of segregation into parallel communities where bonding trust flourishes but bridging trust falters.

The research is clear: diversity itself isn’t destiny. Context matters. Where institutions are strong, integration deliberate, and social contact widespread, trust can recover across generations. But where change is too fast, too concentrated, or poorly managed, trust can erode. Canada’s trajectory over the next decade will depend on whether its institutions can sustain their bridging role under these conditions.

The key takeaway is that scale, speed, and segregation alter the calculus of trust. They make it more uncertain that today’s newcomers will follow the same path of convergence as past cohorts. The danger isn’t simply slower integration but the possibility of an overall decline in social trust.