These days, there is a lot of talk about building export pipelines. Less discussed is the bigger question: How would the upstream industry fill these steel arteries with new oil production?

Pipelines, as instruments of geoeconomic ambition, have reached the country’s highest offices. On Oct. 1st, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith announced the province will be sponsoring a new, one-million-barrel-a-day-plus oil pipeline to the northwest coast of B.C., urging fewer federal hurdles, engaging First Nations, seeding route studies, and rallying private capital. It’s a follow-on to her words earlier in the year when she declared, “The world needs more Alberta oil and gas,” calling for a doubling of the province’s production.

The prize for growing production and generating more export revenue is big for the Canadian economy. Extracting, producing, and selling crude oil and natural gas is one of the country’s largest industries. In 2025, top-line revenue is estimated to reach $177 billion, of which over 90 percent comes from crude oil sales. As such, the business is also one of the most lucrative contributors to public finances, with royalties and taxes expected to total $30.6 billion this year, not including indirect impacts on employment and GDP.

Prime Minister Mark Carney has anchored his stance in Bill C-5 and the new Major Projects Office, which has already put a liquefied natural gas (LNG) project on its initial list. For oil, he has signalled only conditional support. In May, he said, “It’s time to build,” framing any major oil projects around carbon reduction and the need for industry sponsorship. In other words, upstream producers and their pipeline peers must bring forward projects that check multiple boxes—from economic viability to decarbonization plans to Indigenous participation, among other conditions—before Ottawa steps in.

But Alberta is stepping in first to help check those boxes, because exporting more oil remains a high-stakes stalemate, even within the industry. Pipeline companies won’t sink billions without firm shipping commitments, while producers won’t invest in output growth without certainty of new export capacity. And neither will do anything without federal regulatory reform.

In the absence of Alberta’s pitch, it’s a classic which-comes-first dilemma: the pipeline or the oil wells and facilities? Until one stakeholder makes the first move, the prospect of major new expansion remains uncertain. And neither pipe builders nor producers are likely to step forward until the historical script changes.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith speaks during a press conference in Edmonton, Tuesday, May 6, 2025. Jason Franson/The Canadian Press.

A movie seen before

When talking about the odds of building a pipeline, industry pundits are apt to say, “We’ve seen this movie before.”

Over the past two decades, Canada experienced a wave of oil production growth as oilsands megaprojects came online. The early 2010s were a period of remarkable expansion but also hard lessons. Multiple facilities were built at once, straining labour markets, driving up material costs, and creating inflation, delays, and ultimately shareholder frustration. When those projects finally started producing mid-decade, the pipes to move the oil to export markets weren’t ready. The result: nearly 15 years of bottlenecks, with recurring price discounts that forfeited an estimated $49 billion USD from upstream revenue.

In large part, that history explains today’s hesitation for upstream corporations and their investors to propose any new, greenfield drilling and production facilities. With memories of cost overruns, stranded barrels, and billions in lost revenue still fresh, few in the industry are eager to sponsor the next big push if the movie risks ending the same way.

Pipeline-building history has only deepened those doubts. Keystone XL was cancelled after years of political battles on both sides of the Canada–U.S. border. Northern Gateway was approved in 2014 with 209 conditions, only to have its approval overturned politically in 2016. The 2019 Oil Tanker Moratorium Act ensured that any new pipeline to northern B.C. was effectively a brick wall to tidewater. And the Trans Mountain Expansion to Burnaby, though completed in May 2024, came billions over budget and more than a decade behind schedule due in large part to regulatory and court challenges.

In short, producers have learned that betting on pipelines risks losing billions, while pipeline companies have learned that enduring Canada’s drawn-out approvals gauntlet is no less punishing.

That is why today’s debate carries the weight of a bad movie replayed too many times. If Canada’s upstream oil and gas industry is to add another one-to-two million barrels per day of output as the province of Alberta is proposing, the challenge will be not only to align capital, labour, regulatory processes, emissions reductions, Indigenous participation, and competitive viability, but to do so with assurance that pipeline capacity will be there to match production volumes destined to high-value markets—avoiding a rerun of the past.

But that’s the full story arc. For now, let’s take a barrel-half-full view and assume that a new pipeline for up to 1.5 million barrels per day (MMB/d) is coming online. Let’s return to the key question: How much upstream capital investment would it take to develop and produce enough oil to fill those steel arteries?

The ghost of oilsands’ growth past

In the early 2000s, tight global supplies and rising fears of “peak oil”—the belief that aging fields could not keep up with surging demand—drove commodity prices higher. The price signal was heard, and capital investment quickly followed, flowing into exploration and development projects worldwide.

Alberta’s oilsands, holding 166 billion barrels of proven reserves, became a darling for that wave of investment. Over $227 billion poured in over a decade, much of it from foreign multinationals. The region went through two booms: 2005 to 2008 and 2010 to 2014, interrupted only by the Financial Crisis. These surges of capital financed greenfield mines and steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) projects, plus peripheral infrastructure like roads and airfields. Although these investment booms have long passed, the foundations laid during that era still underpin ongoing brownfield production growth in smaller increments.

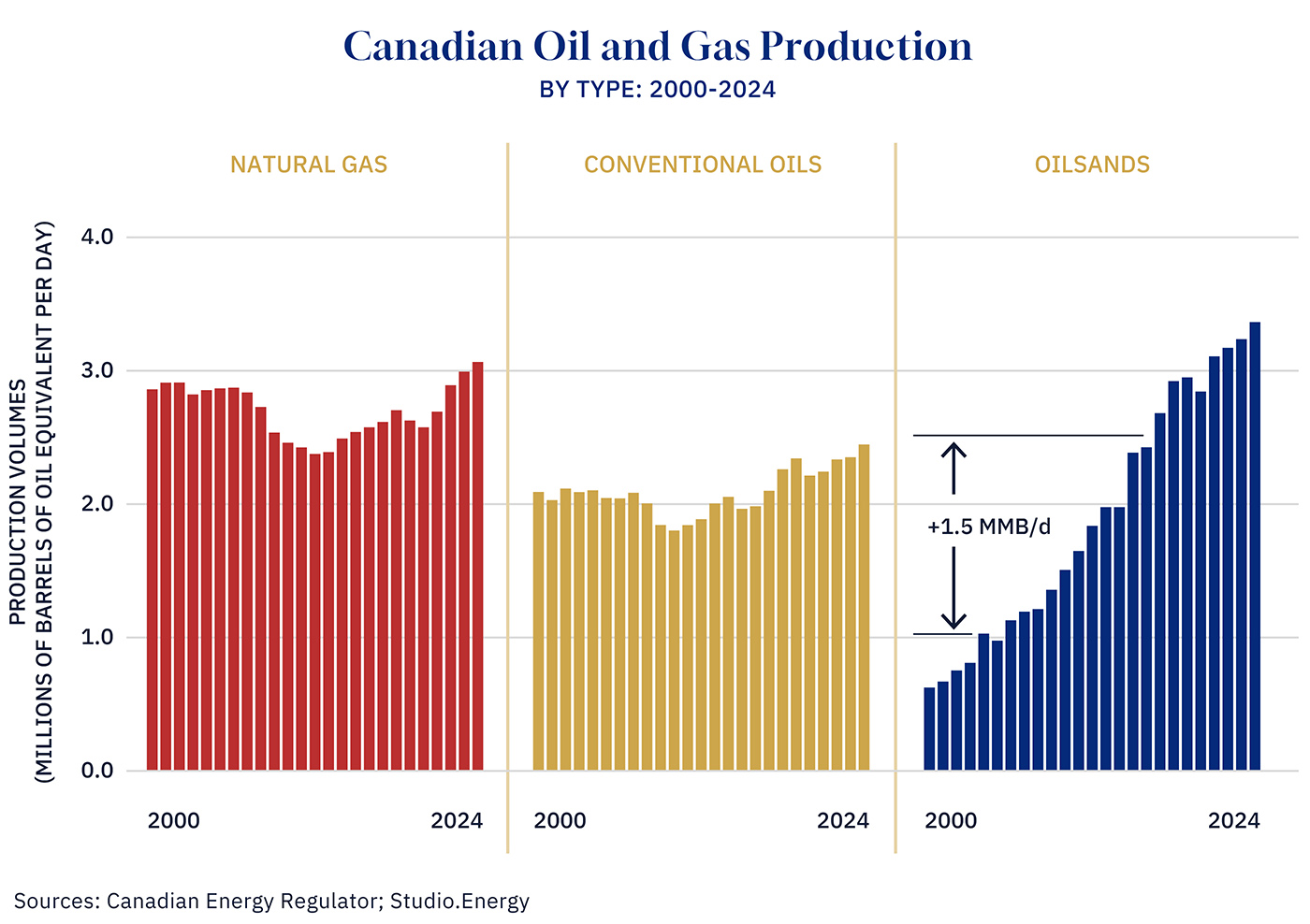

The result of the historical investment surge was transformative. Over two decades, Canada’s oil output nearly doubled, from 3.0 MMB/d in 2005 to 5.8 MMB/d in 2024. As the below chart shows, with conventional oil output only rising mildly; the oilsands provided virtually all that growth.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Notably, the chart also shows that it took over a decade for oilsands output to grow by 1.5 MMB/d between 2005 and 2016. Past dollar amounts and resultant volume increases serve as benchmarks—a prologue—for considering future growth to fill new pipeline expansions.

How much capital will it take?

Filling a new pipeline is not just an engineering challenge but a financing one. Let’s take a closer look at that past $227 billion of investment.

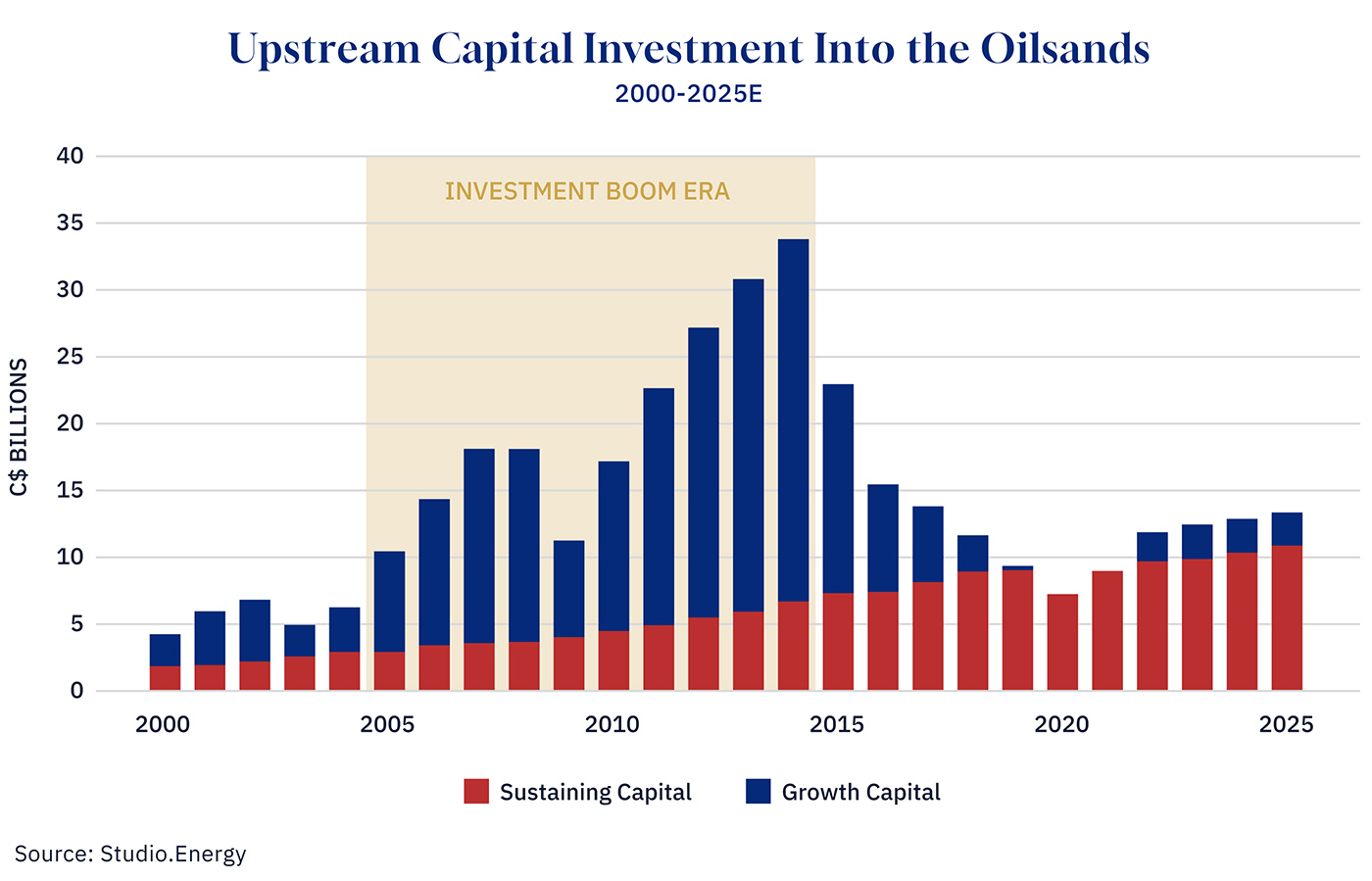

With a smaller base of production in the 2010s, three-quarters of that investment—about $174 billion —went into growth CAPEX (upper blue bars in the below chart) that directly added new barrels, rather than sustaining CAPEX to keep existing output from declining (lower red bars).

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The lesson is simple: As production grows, so does the dollar burden of sustaining the production base. In 2005, sustaining capital was only about $3 billion. By 2025, it more than tripled to about $11 billion. In other words, the first $11 billion of the industry’s cash flow today must be reinvested merely to hold output steady. Growth happens only if spending rises above that threshold.

In 2025, total investment into only the oil sands is estimated to be $13 billion a year. At the moment, that’s leaving only a narrow wedge of just over $2 billion for incremental growth, in the absence of new investment.Canadian Oil and Gas Economic Model, Studio.Energy, 2025

Over the past 10 years, oil sands producers have become adept at optimization and debottlenecking, adding incremental barrels at lower cost. But big step-ups in volume, certainly above 1 MMB/d, would require a return to greenfield projects, likely with higher capital costs than in prior years.

In today’s math, filling 1.5 MMB/d of new pipeline capacity would take roughly a decade of sustained additions—many 30 to 100 thousand barrels per day (kb/d) projects advancing. The front-end-loaded requirement would be at least $100B to fill a big pipe. If a decade is the target, the cadence would need to mirror the last growth cycle, when a surge of capital drove steady builds and expansions.

But unlike that era, today’s upstream industry would have to hold inflation in check, manage labour constraints, ensure Indigenous participation, reduce emissions intensity, and satisfy investors, who are increasingly drawn to high-growth sectors such as AI.

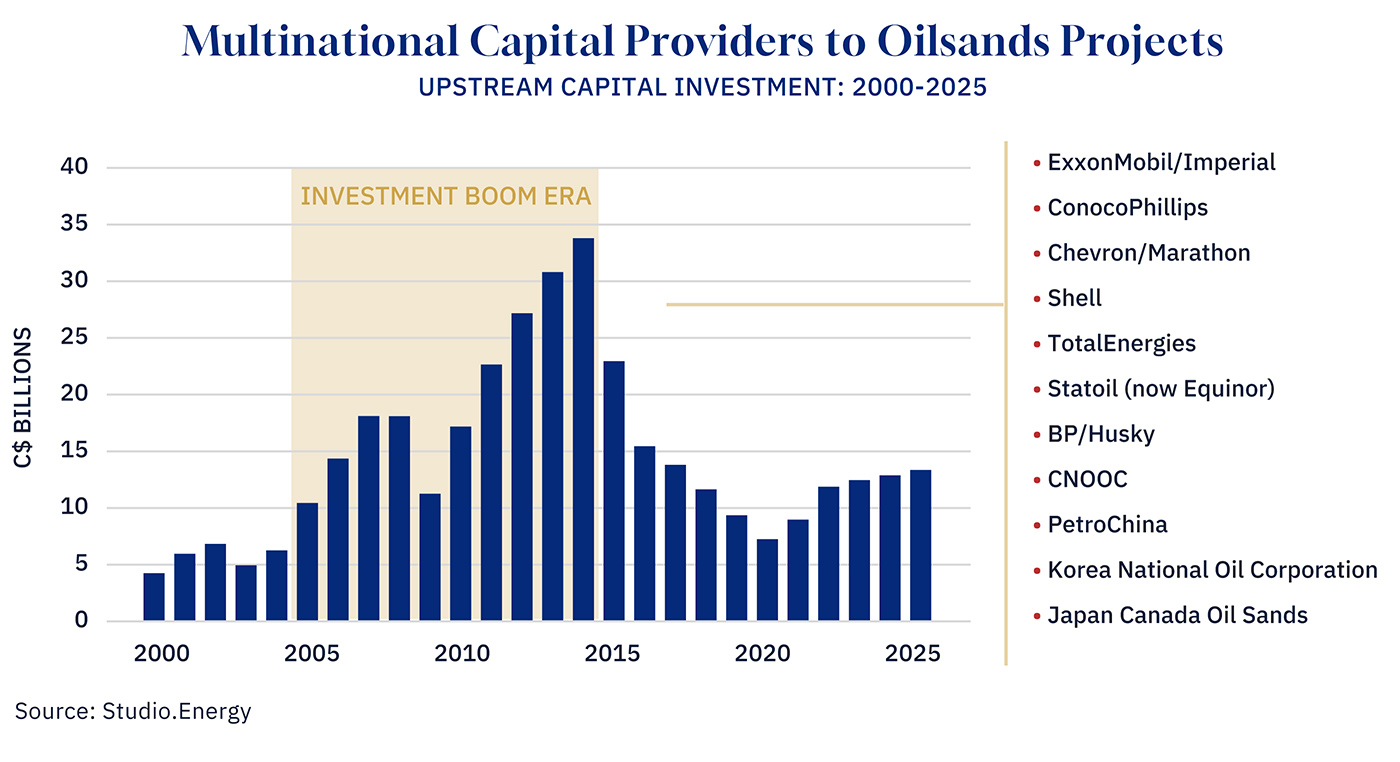

The repatriation of the oilsands

A defining feature of the oilsands boom years was foreign balance-sheet support. U.S., European, and Asian supermajors bankrolled Canada’s multibillion-dollar projects, viewing the oil sands as a rare combination of scale, stability, and security. The chart below highlights the multinational investor base that underpinned the 2005–2014 surge in oilsands CAPEX.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

After 2014, most of those international players exited, and Canadian firms — CNRL, Suncor, Cenovus, Imperial, and Athabasca Oil—consolidated the oil sands assets, representing a repatriation into domestic control. And that shift brought sharper focus and greater operating discipline (not to mention the positive aspects of greater control in Canadian boardrooms), but it also substantially limited the global pool of corporate capital available to finance the next wave of growth. Balance sheets and discretionary cash flows of domestic firms now have less scale than those of the foreign multinationals, companies that once had both the appetite and the capacity to take on multibillion-dollar risk.

Efficiency gains and debottlenecking can still extend the life of existing assets, potentially delivering up to a few hundred thousand barrels of additional supply. But that outcome depends on incumbents boosting their capital investment above today’s meagre $2 billion per year. To grow that million-plus-barrels-per-day would require stronger commodity prices and a green light from investors to recycle about $10 billion per year of their cash returns back into funding more production. In the absence of that, new sources of investor capital from foreign multinationals would likely be required.

All this sounds extraordinary. Yet the last time this movie played, the opening scenes were full of excitement. Canada was seen as a desirable place to invest, a place where vital commodities could supply the world in greater quantity. In today’s geopolitical environment, that part of the old movie is emerging as the easy one to rescript. In Asia-Pacific refineries, Canada’s heavy oil is increasingly in demand. The rest of the script is ours to write.

This article was co-authored with help and research by Carmen Velasquez, Studio.Energy.

Comments (0)