Canada’s investments in the United States aren’t a “trillion-dollar gift.” They’re the natural result of deep, long-standing ties between our two economies—and they reveal something important about Canada’s own competitiveness.

Prime Minister Mark Carney recently underscored this point after meeting with U.S. President Trump. He noted that Canada is already the largest foreign investor in the U.S., with nearly $500 billion flowing south over the past five years, and projected that this could reach $1 trillion in the next five.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre quickly seized on the remark, calling it a “trillion-dollar gift” to the Americans. “Where in his platform did he promise to give a trillion of our investment dollars to the Americans?” he asked.

But that framing misses the mark. Is a trillion dollars unusually large? Does it signal capital leaving Canada at our expense? The data suggest otherwise. Far from a giveaway, these flows reflect the depth of Canada–U.S. economic integration—if anything, Carney’s estimate may understate it. And that might be the real problem.

What the numbers actually say

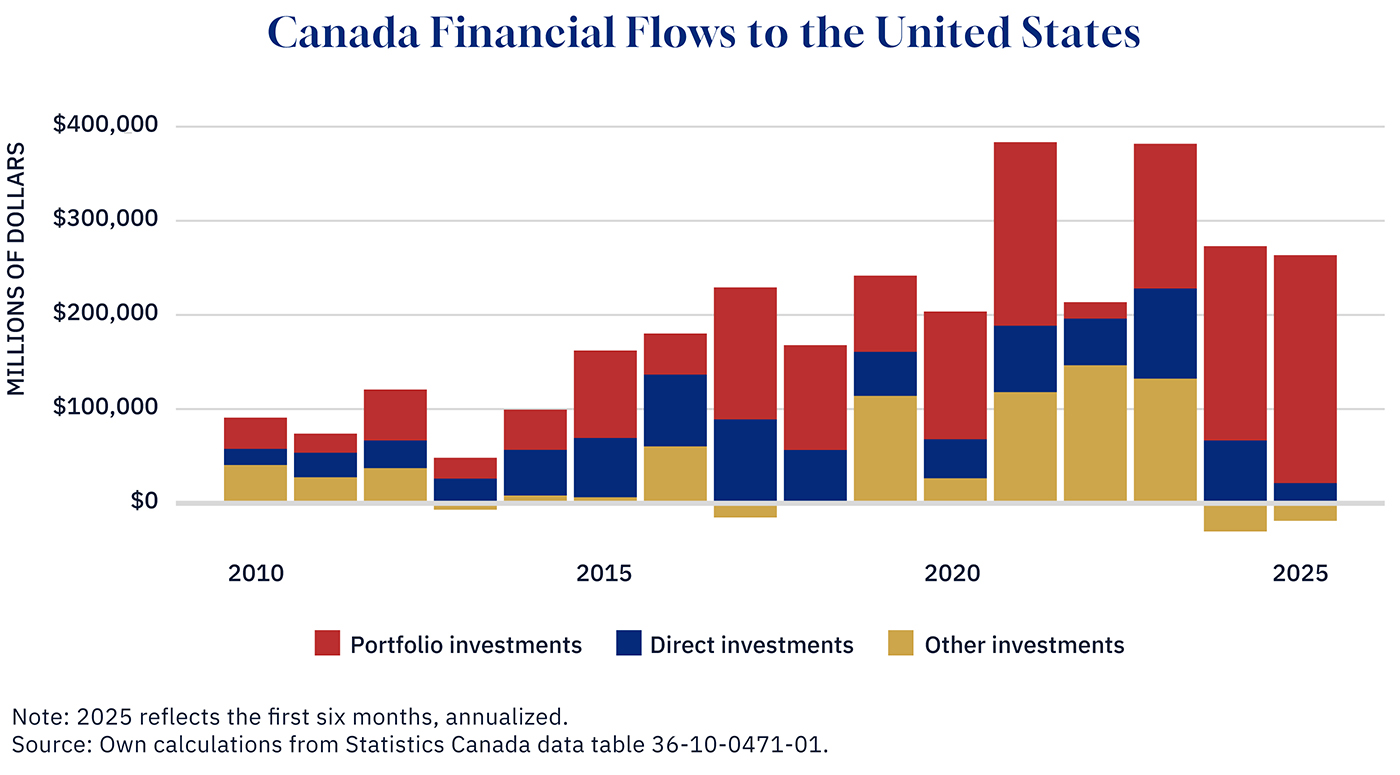

Canadian capital flowing to the U.S. is nothing new. In 2024 alone, Canadians invested about $250 billion south of the border—roughly half of it through individuals buying American stocks and bonds, the rest through businesses expanding operations there. Over the past five years, total investment exceeded $1.4 trillion.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

The prime minister’s “$500 billion over the past five years” figure likely referred to direct business investment, which has grown steadily—from $730 billion in 2019 to nearly $1.3 trillion in 2024. But the broader story is that both households and firms see strong returns in the U.S., and have for decades.

Who’s investing—and why it matters

These figures don’t reflect government spending. They reflect the decisions of individual Canadians—through RRSPs and TFSAs, for example—and Canadian businesses seeking returns in the U.S. economy. This isn’t charity. These are income-generating investments made to fund retirements, support business operations, and drive economic gains on both sides of the border.

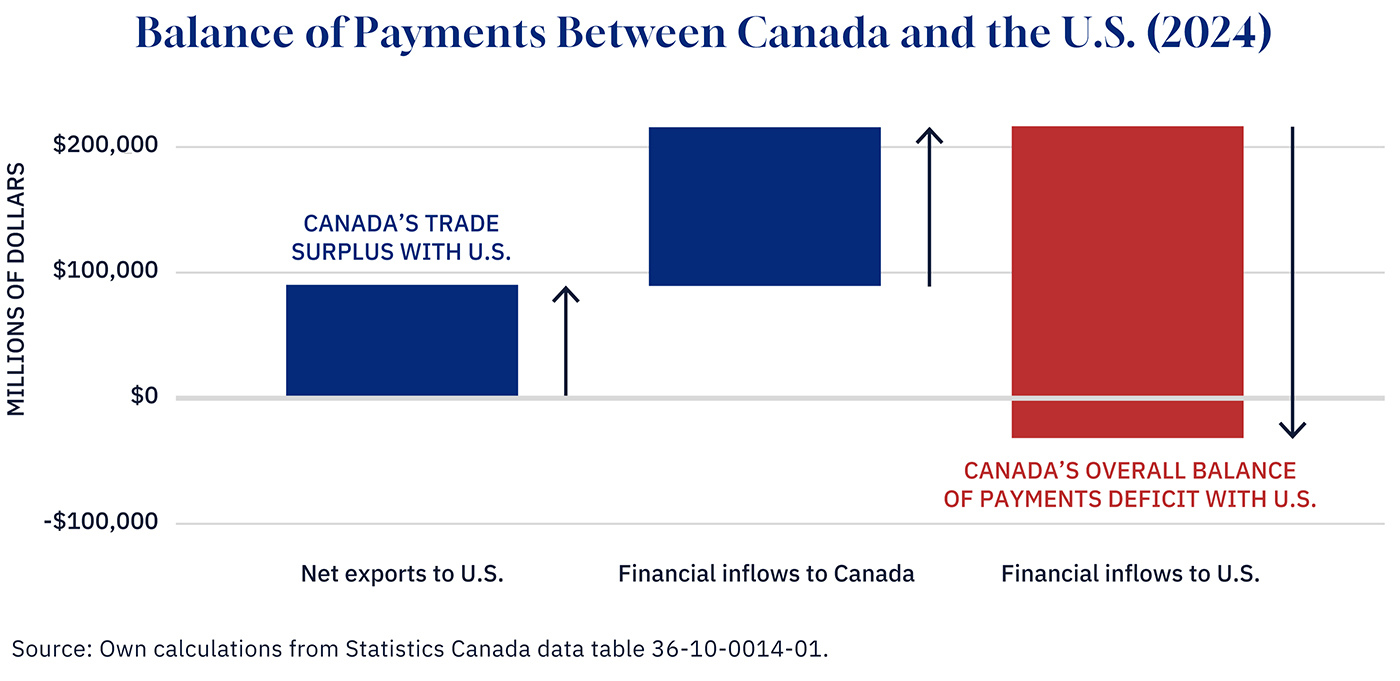

It’s also important for Canadian leaders to highlight these capital flows, particularly as President Trump continues to emphasize trade imbalances as justification for tariffs. While he hasn’t clearly explained why a trade deficit should matter to the U.S., the implication is that it represents a net outflow of wealth to Canada. That isn’t the case. Trade, after all, is mutually beneficial. And when capital and current account flows are combined, there’s a consistent net outflow from Canada to the U.S.—modest in 2024, but even larger in prior years.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

Last year, the net flows to the United States from Canada totalled nearly $31 billion. Modest, yes, but anything but a U.S. deficit. Highlighting this fact can potentially help smooth negotiations if it means the president is less focused on trade flows.

A deeper issue

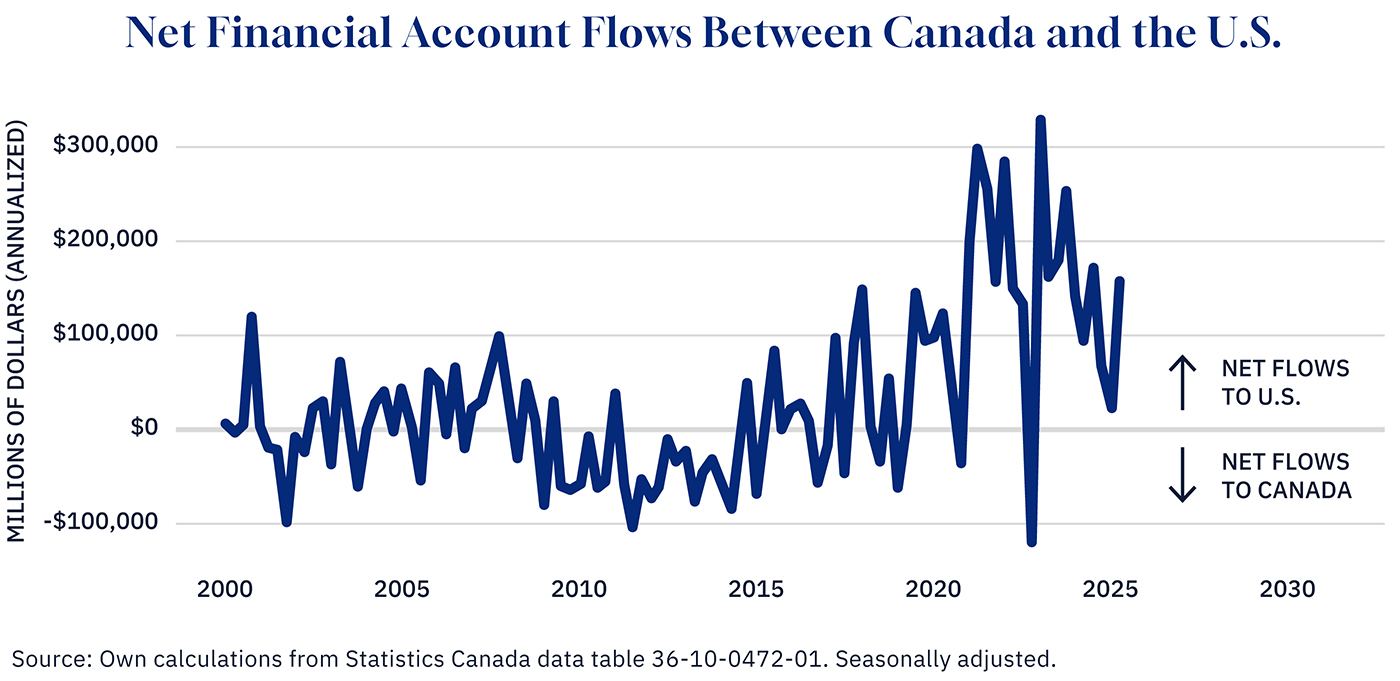

But if Canadian money so reliably flows south, we should ask why. For years, direct investment into the U.S. has outpaced American investment here. That imbalance points to a deeper problem: Canada has made it harder, not easier, to invest at home.

Before 2015, investment flows between the two countries were roughly balanced (depending on the year). Since then, Canadian policy has increasingly emphasized environmental and social goals over economic competitiveness—an area ripe for debate, but not without consequences for growth and productivity. Overly stringent regulations, especially in capital-intensive sectors, and higher marginal tax rates can lower the after-tax rate of return on investments and therefore lower the incentive to invest in the first place.

Graphic credit: Janice Nelson

With capital accumulation such a critical part of labour productivity growth (and therefore of our average living standards), this recent trend is a warning sign.

In fairness, the federal government and several provinces have started to recognize this problem. Ottawa’s recent measures to speed up selected project approvals and simplify permitting processes through Bill C-5 are a start. And various provinces, notably Nova Scotia and Ontario, have moved to boost internal trade by easing barriers there. These are steps in the right direction. But Canada’s regulatory and tax environment still lags.

Reframing the debate

If we want more of our own savings and capital to stay here at home—funding new plants, equipment, and technologies that raise productivity—then a more flexible and competitive business environment to increase the returns to investing in Canada’s economy is essential.

This is where the opposition may better aim its fire. There is so much that federal and provincial governments could do to improve our economy. An opposition holding the government’s feet to the fire to push these needed reforms forward is critical. Mischaracterizing outbound investment as a “gift” only confuses the public and distorts the nature of our economic relationship with the U.S.

If highlighting existing Canadian investment in the U.S. helps avert disruptive American trade actions, so much the better. It costs Canada nothing and may serve President Trump’s political needs. While showcasing the capital already flowing south—and what may yet come—seems wise, there’s much we can and should do in the meantime to make Canada a more attractive place to invest once again.

Is Canadian investment in the U.S. truly a 'trillion-dollar gift,' or does it reflect deeper economic ties?

Why is Canadian capital increasingly flowing to the U.S., and what does this imply for Canada's competitiveness?

How can highlighting Canadian investment in the U.S. benefit Canada in its economic relationship with its neighbor?

Comments (6)

You did happen to see the $ net outflow graph included in the article, didn’t you?

Pretty much flat with $ flowing into Canada until about 2015, then a pretty sharp reversal with $ going more & more to the USA.

I wonder what else might have happened in 2015?

Hmmmmmmmmm…………..