Prime Minister Mark Carney’s first budget is leaving some Canadian economists concerned about the mounting national debt and ballooning annual interest payments eroding more and more of scarce federal resources. The “Canada Strong Budget 2025” projects that, by 2029, federal debt charges will consume one in every eight dollars of revenue Ottawa expects to bring in.

The Liberals’ budget, released this week, not only swaps out reducing the debt-to-GDP ratio for the more modest goal of reducing the deficit-to-GDP ratio, but also projects annual interest payments on the debt to swell due to large deficits, starting with a $78.3 billion shortfall this year. In two years, interest payments on the national debt will exceed Ottawa’s annual deficit, with $66.2 billion to service the debt compared to a $63.5 billion deficit.

“It’s essentially doubling down on what the Trudeau government strategy was, and in many cases, is actually accelerating spending, deficits, and debt compared to the Trudeau government’s fall economic statement,” Jake Fuss, Fraser Institute director of fiscal studies, told The Hub, adding that deficit spending over the next five years is almost double what the Trudeau government had planned last year.

By 2029, the compounding federal debt is forecasted to cause interest payments to surpass Ottawa’s combined transfer payments to the provinces for health care and child care. That fiscal year, the federal government projects public debt charges will hit $76.1 billion, while the Canada Health Transfer ($65 billion) and Canada-wide early learning and child care ($8.5 billion) will cost taxpayers a combined $73.5 billion—or $2.6 billion less.

The Carney government’s inaugural budget promises “generational investments” of about $280 billion over five years on new infrastructure, productivity and competitiveness, defence and security, and housing. But some economists believe these “investments” will merely result in costly failed programs similar to the governments of Justin Trudeau and Pierre Trudeau.

“During Pierre Elliot Trudeau’s tenure, [the government] thought that they could judge things best. They brought in the National Energy Program. And they started supply management…going through the list of things, you often see these things blow up,” said Jack Mintz, a president’s fellow of the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary. Mintz believes Carney’s technocratic approach, where the federal government acts as an investment banker picking winners and losers for major investments, will more than likely exacerbate federal spending, debt, and interest.

“You’re squeezing out other public expenditures. You’re also potentially squeezing out other private investment, because as the government requires more and more money from the international market, it starts bidding up interest rates in Canada,” Mintz said to The Hub. He added that as the government drives up the demand for borrowing—while also making Canada a riskier investment by making poor investments—interest rates can surge.

All in all, the Carney government plans to rack up a cumulative deficit of $320 billion over five years, growing the net debt from $1.48 trillion to $1.80 trillion (2029-30) in four years.

And on cue to the added borrowing load announced by the Carney Government, on Thursday one of the world’s three major credit rating agencies, Fitch Ratings, downgraded Canada’s credit score from triple-A to “AA+/Stable” due to “persistent fiscal expansion and a rising debt burden weaken[ing] its credit profile.” The top-three credit agency also warned Canada’s increased borrowing may “increase rating pressures in the medium term”—in other words, increase the interest rates on the growing federal debt.

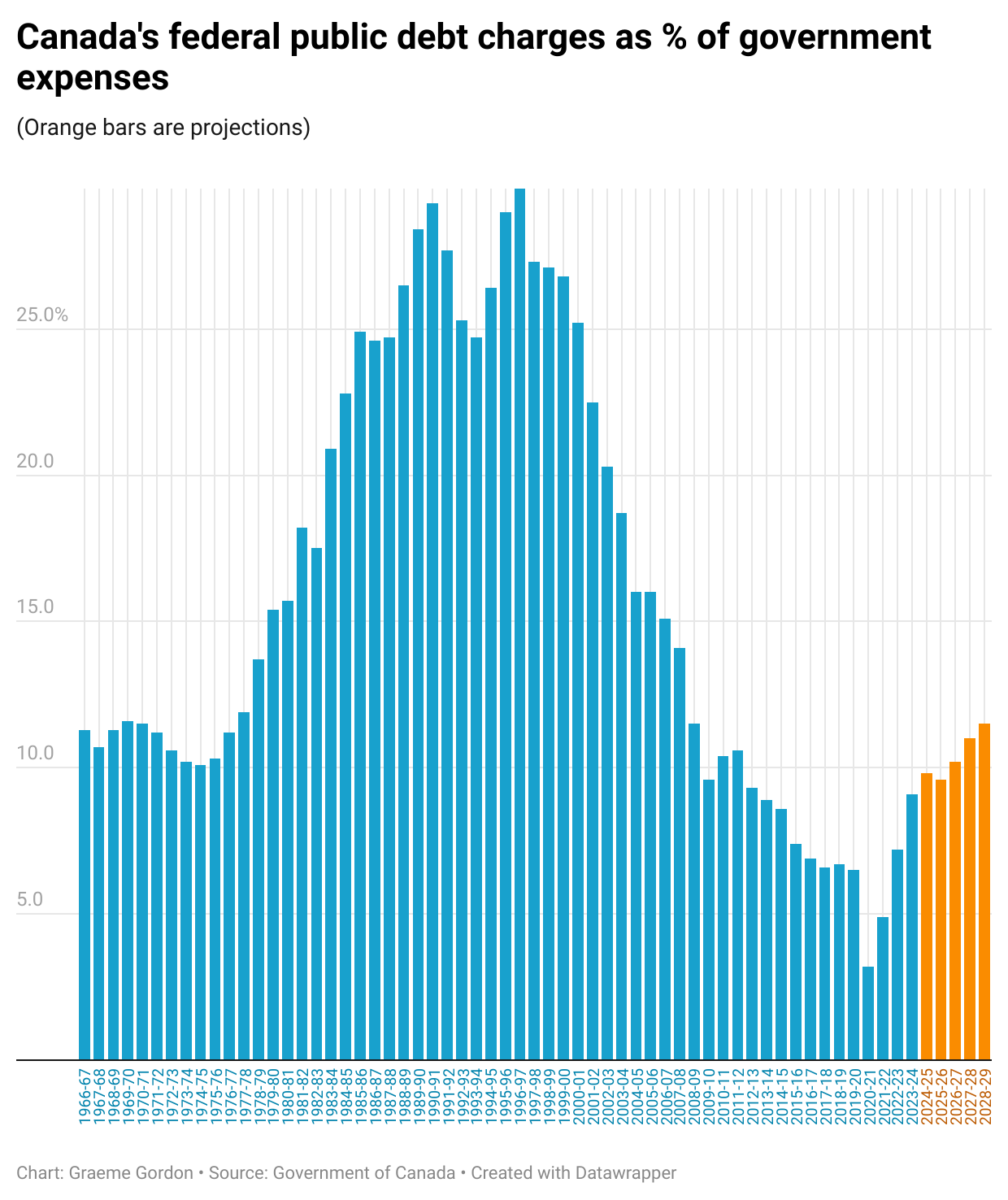

Although interest payments on the national debt are projected to only inch up from 1.8 percent of GDP this fiscal year, to 2.1 percent of GDP by 2029-30, Fuss says Canada may be headed for a dire situation in the not-too-distant future mirroring that of the ‘80s and ‘90s, when interest rates skyrocketed to a point where Canada’s interest payments on national debt hit 6.5 percent of GDP in 1990-91.

“Debt interest costs consumed about 7.5 percent of revenues when the Trudeau government took office in 2015; by the end of 2029, they’re going to consume about 13 percent of revenues,” Fuss explained. “Obviously, we’re not quite in the situation that we were where one in every three dollars of revenue was going to debt interest payments back in the 1990s, [but] we’re definitely going in that trajectory.”

This fall, the Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates the public debt payments will hit $55.3 billion this fiscal year, slightly under the government’s own projection of $55.6 billion. If the PBO’s projections remain accurate, taxpayers will be paying somewhere in the vicinity of the PBO’s estimate of $82.4 billion in interest payments for the 2030-31 fiscal year (the budget only set projections until 2029-30).

Carney’s budget already mentions that the interest rate trendline has caused interest payments on the national debt to rise “over the forecast horizon primarily due to increased borrowing requirements and long-term interest rates [going up].” Interest payments on the national debt could be adversely affected by unforeseen higher interest rates in two ways: the maturity of existing debt needing to be refinanced, as well as the higher cost of required future borrowing.

Debt interest payments could be even higher if budget projections continue to underestimate actual federal spending. As C.D. Howe Institute president and CEO William Robson highlighted in The Hub earlier this week, the federal government’s spending estimates have been leaping more than $20 billion every year.

Is Canada deeper in the red than the budget lets on?

In the budget, the Carney government touts Canada as having the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio in the G7 at 13.3 percent, compared to the next lowest country, Germany, at 48.7 percent. The G7 average debt-to-GDP ratio is 101.4 percent (excluding Canada).

“The federal debt-to-GDP ratio will remain stable over the budget horizon. We also have one of the lowest deficits in the G7, and one of the strongest fiscal positions in the world,” Finance Minister Champagne told the House of Commons. “We must use this fiscal firepower to make generational investments.”

However, economists believe that Canada’s net debt is highly misleading because it includes the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Quebec Pension Plan (QPP) as assets.

“Net debt essentially looks at the total amount of debt, and then it subtracts out financial assets. But included in our financial assets in Canada are the CPP and the QPP, which are valued at about a combined $890 billion in mid-2025,” Fuss said. “And we can’t use those financial assets to actually offset total debt, because we would be compromising the benefits of current and future pensioners.”

Other G7 countries, like the U.S., include pensions as both an asset and a liability, so they aren’t subtracted from net debt like Canada does with CPP and QPP.

“A more accurate measure of Canada’s indebtedness is to look at…total liabilities or gross debt. And if we look at our total debt as a share of the economy, we actually rank fifth-highest among G7 countries at 113 percent of GDP,” Fuss explained. “That’s higher than the total debt burden in the U.K. It’s also higher than Germany, and we’re close behind France as well.”

Is Canada's debt trajectory sustainable, or are we heading for a fiscal crisis?

Should the government act as an 'investment banker' picking winners for major projects?

How does Canada's calculation of 'net debt' potentially mislead about its true indebtedness?

Comments (2)

You know it’s not a great idea when you hear were going to spend our away out of debt.