- The review of “The Coutts Diaries” offers a critical yet valuable historical perspective on Jim Coutts’s role in the Trudeau government.

- The author expresses a strong personal dislike for Jim Coutts, finding him self-absorbed and driven by partisan interests.

- Ron Graham’s editing is praised for making the diaries readable and filling in gaps left by Coutts’s self-centered account.

- Coutts’s diaries reveal a conflation of the country’s interests with the Liberal Party’s political utility.

- The book provides insights into the social dynamics and inner workings of the Trudeau government and its key figures.

- Coutts’s significant gambling problem is revealed as a leitmotif throughout the diaries, contrasting with his focus on government spending.

Review of The Coutts Diaries: Power, Politics, and Pierre Trudeau 1973-1981 (Sutherland House Books, 2025), edited by Ron Graham.

I don’t like Jim Coutts.

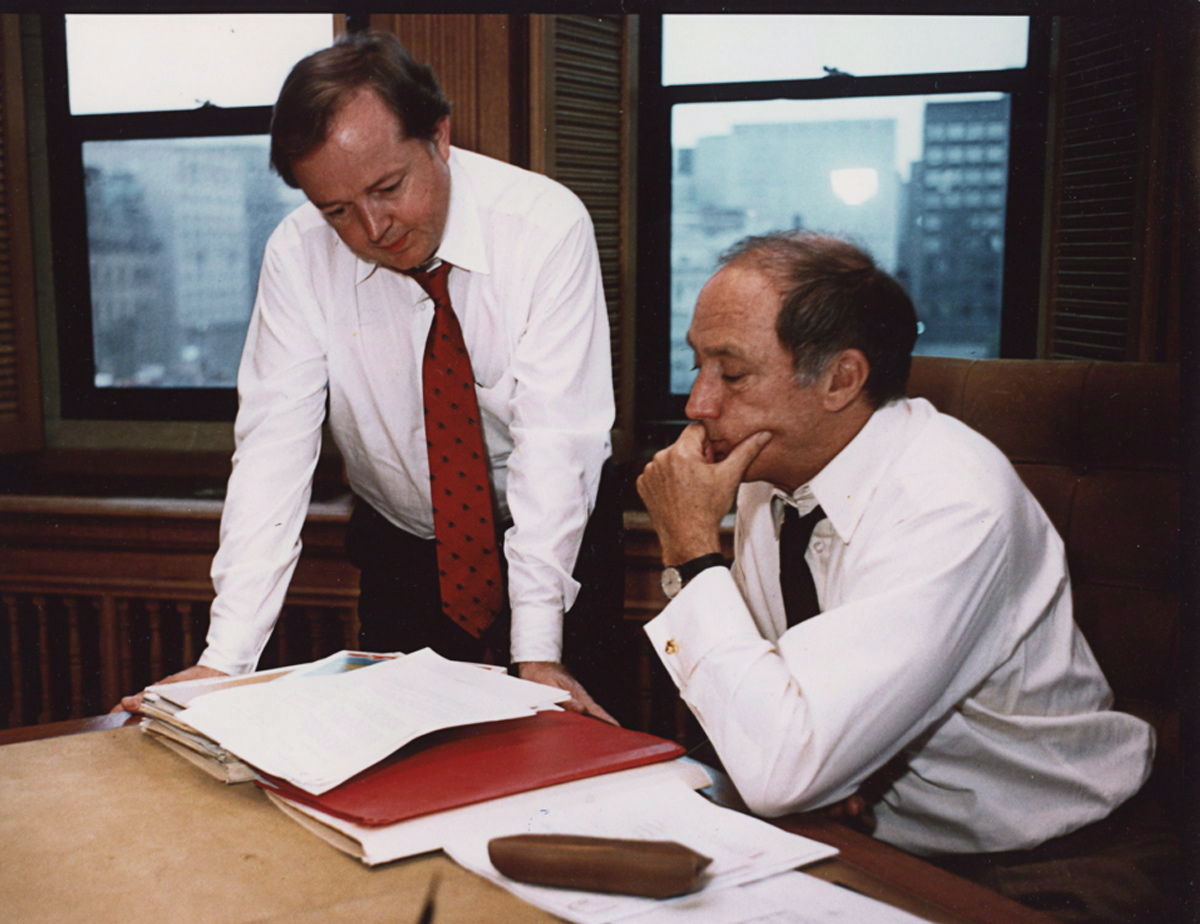

From the first time I set eyes on him, staring back at me from the dust-jacket of this book on Christmas morning, I knew I wouldn’t like him. I didn’t like his pudgy cheeks. I didn’t like his lopsided grin. I didn’t like his high-domed forehead or his wispy hair. And when I opened the book and saw more photos, I didn’t like them either. I didn’t like his cartoonish 1970s collar and tie, his satisfied mien, or pretty much anything else about him. I’m also fairly certain he broke my left foot when the book fell on it, unshod. It landed end down, maliciously aimed at my exposed second and third metatarsals. Whether he intended it or not, it didn’t improve my opinion of Coutts, and my foot is still throbbing as I write this.

Now that I’ve read the diaries of Pierre Trudeau’s longtime political factotum, my first impression stands, but I am darn glad he wrote them, that Ron Graham took the time to edit this book, and that Sutherland House took the chance on publishing it. It’s a handsome volume of historical importance. The readability is significantly aided by Graham’s sensitive editing, sparing footnotes, and thoughtful chapter introductions that fill in the blanks Coutts’s self-absorbed account leaves out. We couldn’t hope for a better guide to the era of the diaries than the author of One Eyed Kings and The Last Act: Pierre Trudeau, the Gang of Eight, and the Fight for Canada, who was there and saw the story unfold firsthand.

Canada has not been blessed with many great political diarists, the great exception being Mackenzie King. Like the Americans, our political class prefers memoirs, which give the author the advantage of recalling events in hindsight. This has significant advantages for the author, if not the seeker of truth. Then-prime minister Harper once told me that political memoirs fall into two types: the “see, I was right about everything all along” type, which aren’t reliable, and those that are honest, which means offending friends and former colleagues who are revealed for the flawed and fallible men they are. We will see which category his memoirs fall into when they are eventually published.

The British, on the other hand, have a mania for diaries. From Samuel Pepys, who invented the genre and has never been bettered, to Chips Channon’s waspish social commentary–Anthony Powell meets Anthony Blance–to Tony Benn’s seven meticulous volumes, to Alan Clarke’s scabrous, scandalous entries (uniquely, published while he was still a sitting MP), to Gyles Brandreth’s brutally candid account of life at the periphery of the Major government, British diarists set the gold standard. Learned, literary, and ripe with gossip, they show that the reason British upper lips are so stiff is to conceal the sneer underneath.

Coutts’s diaries are not literary. A few short passages show a talent for descriptive prose that one wishes he had indulged more often. A verbal pencil sketch of the view of Saint-Gédéon-de-Beauce from the window of the Motel Bel Rive (April 17, 1979), a flock of gulls circling Parliament Hill above the Ottawa River (November 12, 1980), and several lovely descriptions of the Alberta foothills near Pekisko, where the Prince of Wales had his ranch and Coutts imagines building a cabin near his old family homestead stand out vividly. I may be alone in feeling that it would have been better for the country and for Coutts’ soul if he’d opted for travel writing over politics.

But politics is what readers of political diaries want, and here they won’t be disappointed. Coutts gives us the view not just from the centre of the Trudeau government, but of the man who, for the most part, directed Canada’s domestic policy for a decade. If he had done it for the good of the country, he might be remembered as a great Canadian. Unfortunately, as the diaries make clear, he did it for the benefit of the Liberal Party, and we are still paying the price. Much of Alberta’s current alienation, for example, can be traced back to Coutts’ personal intervention to insist on stricter terms for the National Energy Program than the government was prepared to offer (June 19, 1980).

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (C) accompanied by Allan MacEachen (R) Rene Levesque , (FR), Jean Chretien, (L), and Bill Davis, (FL) at the Constitutional conference Nov. 5, 1981. Ron Poling/CP Photo.

Coutts was an Alberta Liberal, and it’s an open question whether one can authentically be both. Coutts, I suppose to his credit, never bothered to try. He seems always to have been an aspiring Laurentian, which in Canada is more a state of mind than a geographic marker. A Laurentian may come from Nanton, like Coutts, or even Fort Smith, like Mark Carney. I assume that Coutts never married because the Liberal Party of Canada was his great passion. This can make the diary’s partisanship cloying at times. In Coutts’ telling, Tories are all dimwits unless they are being personally helpful to him, and businesses and provincial premiers who disagree with the government are selfish and unpatriotic (June 26, 1980).

The conflation of country and party is brazen. As Jeffrey Simpson wrote at the time, “Coutts viewed policy from the exclusive perspective of its political utility in enhancing the Liberal Government’s popularity.”Jeffrey Simpson, Discipline of Power: The Conservative Interlude and the Liberal Restoration, p 7. The diary vindicates this assessment. The politically-appointed Clerk of the Privy Council participates in election planning with the senior PMO staff; government planes ferry Coutts to and from Liberal Party events; and cabinet discussions move seamlessly from policy considerations to partisan calculation, and it’s clear that in Coutts’ mind he sees no difference. You might say this is just politics, but I had a job not unlike Coutts’ working for a different prime minister, and I can tell you it isn’t, or doesn’t have to be.

View reader comments (3)

The best parts of the diary are when Coutts offers his private opinion on public figures and events that have passed into national lore. An extended account of Ronald Reagan’s visit to Ottawa in March 1981, including a private dinner with Pierre Trudeau, is particularly fascinating. It also shows how someone as smart as Coutts can be at the same time so insightful in his observations and so wrong in his assessment (Coutts is convinced “Reaganism” is doomed to fail fast). Beyond these set pieces, there are not many extended character sketches, but a sense of the major recurring characters emerges from a profusion of asides. Jean Chrétien: moody, difficult, ambitious; Paul Martin, Jr.: anxious, petulant, impatient; Trudeau: Apollonian, detached, cerebral; Paul Desmarais: eager, comforting, thoughtful; Keith Davey: competent, occasionally peevish; Michael Pitfield: academic, methodical, a worrier.

The overall impression of the Liberal Party is one of dynastic and incestuous tribalism. The pages are littered with complex relationships. There’s Michael Pitfield, father of Carney’s current principal secretary; three Rae siblings, including “Bobby” and Jennifer, who dated Trudeau before becoming Coutts’ unrequited love interest; the Axworthy brothers, Tom and Lloyd; the Ignatieffs, senior and junior; the Martins, senior and junior; and young Justin Trudeau, whom Coutts chides for his crassly political eulogy at his father’s funeral. And flitting between them all is Coutts, a louche Screwtape in the body of a debauched choir boy, looking out for his friends, simpering to power, and froward when denied his way.

Speaking from my own experience inside Ottawa, I was struck by how much more social life was before smartphones. The issues may not have changed much–the diary deals with fighter plane purchases, auto bailouts, Quebec separatism, Western alienation, and a Liberal government making nice with a centrist Ontario PC Premier–but the way of handling them has. Thinking back to protein bars consumed at my desk, I envy their long lunches and long dinners. In Coutts’ Canada, there are only about 100 people who matter. I suppose that hasn’t changed, though, allowing for population growth, there are now perhaps 200. Today, they can be found in dozens of overlapping WhatsApp chats; back then, they could be seen together in the flesh–often, if Coutts’ experience is typical, in the grill rooms of the nation’s leading hotels.

Coutts’s account of this lost world lines up with the splendid sketch of him in Christina McCall-Newman’s Grits, which is too delicious not to quote in full:

He would sit on the velvet banquette like an Irish landowner on rent day, bestowing his benign interest on the waiters (“How’s your wife, Pasquale?”), ordering the same food and drink (martini straight up, minced steak medium rare, sliced tomatoes, black coffee, and then, oh sin, oh sweet sublimity, a fat chocolate cream from the silver bonbon dish that was brought only to the tables of the favoured), dropping his pearly perceptions for the benefit of his guests, waving in acknowledgement as privy councillors and deputy ministers respectfully passed by, his clear eyes surveying, small presence commanding, the room that lay before him. It had taken Coutts a quarter of a century to propel himself to that table and he was shrewd enough to savour its significance.

The Coutts that emerges from his private diaries is little more vulnerable than this, and frequently more sorry for himself, but all the smarm and arrogance are still there. So too is an astonishingly reckless and serious gambling problem.

Looking back at his time in politics, Bismarck compared the job of a statesman to “gambling for high stakes with other people’s money.” A leitmotif of Coutts’ diaries is the weekly record of his winnings and losses at his late-night poker game. Coutts records more losses than wins, some of as high as $40,000 (in today’s money), in whisky-fueled games that often ran to 3 am and occasionally to 8 am, even on week nights. Given his obsessive concern with the loss of his own money, there is curiously little attention to the Trudeau government’s squandering of Canadians’ money. Nothing, not even a spiralling national debt, could be allowed to stop the Liberal way of politics, in which to govern was to govern politically and to govern politically was to spend profligately.

At least the story has a happy ending. After years of public and private speculation about running for Parliament and dozens of discussions with Pitfield, Davey, and Trudeau about exactly how quickly he will enter cabinet once elected, what portfolio he will have, and when he will begin his run for leader and prime minister, Coutts finally tossed his hat in the electoral ring in the summer of 1981. It was, naturally, in a by-election that he engineered specially for himself in the safe Liberal seat of Spadina after the incumbent was pushed out and up into the Senate. Coutts lost by 214 votes. Alas, the diary ends just days before his defeat,There is a brief epilogue of diary entries that covers Pierre Trudeau’s death and funeral in 2000. so the reader is denied Coutts’ reaction to his overdue comeuppance. After being subjected to almost a decade of grandiose pretensions from this jumped-up partisan majordomo, we are left to imagine his humiliation alone. It’s nothing less than the man deserved.

In this review of The Coutts Diaries: Power, Politics, and Pierre Trudeau 1973-1981, Howard Anglin writes that the book presents a “frustrating” yet historically important look into the life of Pierre Trudeau’s political advisor, Jim Coutts. The review highlights Coutts’s partisan focus, conflating party and country, and his role in shaping policies that have had lasting negative consequences for Canada, particularly Alberta. The diaries also reveal Coutts’s social maneuvering, personal flaws like a gambling problem, and his eventual electoral defeat.

Did Jim Coutts prioritize party over country? Discuss.

How did the social dynamics of Ottawa politics differ then vs. now?

What economic policies of the Trudeau era are still debated today?

Comments (3)

Bravo, Howard. This confirms all my darkest thoughts about the Trudeau era. And his “Alberta advisor”–Jim Coutts.