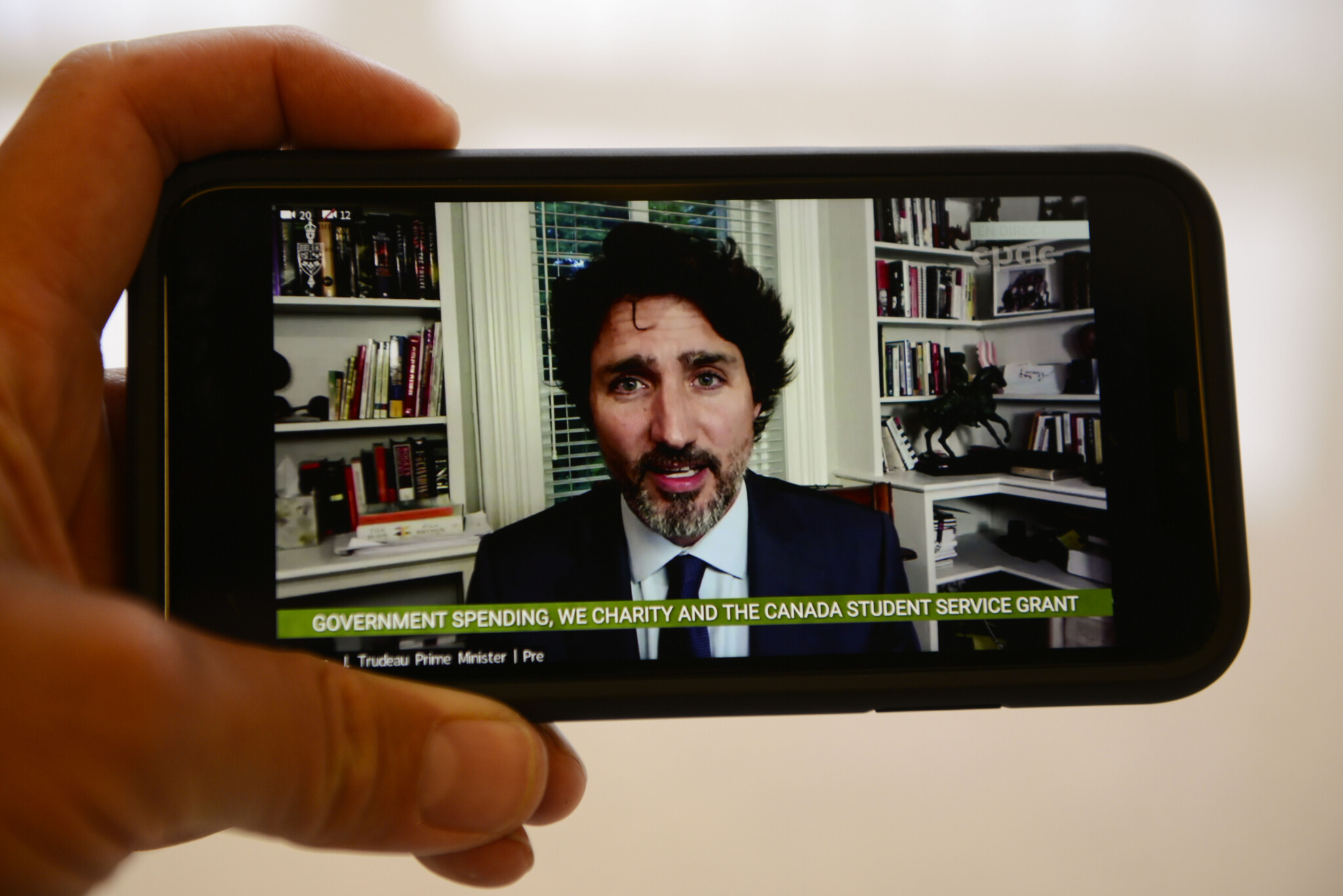

The Supreme Court of Canada has recently heard final arguments in a case that reopens the WE Charity controversy and tests how Canadians can challenge ethics-watchdog findings.

I respectfully submit to our highest court: this is not the moment for a fulsome investigation. It’s the moment for a thorough, thoughtful one.

The distinction matters.

In ethics investigations, politicians and jurists have embraced “fulsome” with gusto.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre issued a clarion call for a “fulsome audit” of the Trudeau Foundation in an April 2023 post on X.

Our House of Commons has fallen in love with “fulsome,” more than 2,800 instances and counting.

So have our appeals courts and tribunals. More than 2,600 rulings contain the malodorous word.

Our parties and public intellectuals have hijacked a word the Oxford English Dictionary calls cloying, disgusting, and excessive to the point of insincerity. “Fulsome” boasts steady growth from 1990–2022 in Google Books’ English-language corpus, doubling in relative frequency.

When politicians speak of energy consultations or Indigenous partnerships or fiscal policy, the word pops with a metronomic beat. Discussing the One Economy Act, Liberal parliamentarians promised that “fulsome consultation will be pivotal to the success of future projects.”

Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language defined “fulsome” plainly: “nauseous; offensive… a rank and odious smell.” The stench suits Shakespeare’s King Lear, mad and incoherent, wandering the countryside.

In Canada, the same people who think “impactful” sounds profound have, I suspect, hijacked “fulsome” to mean “fullness.”Across the Atlantic, Britain’s political class has embraced the word with equal enthusiasm and equal ignorance.

Consider Rishi Sunak. In April 2024, the then-prime minister found himself embroiled in a controversy of surpassing triviality: he had worn Adidas Sambas, a sneaker of choice for discriminating young Londoners, thereby committing the unforgivable sin of trying too hard. Under pressure from the Samba lobby, Sunak capitulated. “I issue a fulsome apology to the Samba community,” he told LBC Radio.

Fulsome. The word choice was exquisite in its awfulness. An apology for wearing the wrong shoes, delivered with language suggesting insincerity so thick you could spread it on toast.

Britain’s outgoing Prime Minister Rishi Sunak speaks outside 10 Downing Street in London, Friday, July 5, 2024. Vadim Ghirda/AP Photo.

More recently, Sir Keir Starmer, the current prime minister, a Leeds-and-Oxford barrister who speaks with the careful joylessness of a man reading terms and conditions, offered a still more telling example. On December 27th, he announced his “delight” at the return of British-Egyptian activist Alaa Abd el-Fattah from an Egyptian prison. Then surfaced Abd el-Fattah’s odious social-media posts: calls for violence against “Zionists” and “white people,” the sort of activism that resists tidy contextualization.

Facing a bipartisan rebuke, Abd el-Fattah apologized “unequivocally.” The posts, he said, were “shocking and hurtful,” merely “expressions of a young man’s anger.” Mr. Starmer’s anonymous spokesman declared the renunciation “a fairly fulsome apology and that’s clearly the right thing to do.”

Fulsome? The effrontery.

An apology can be unreserved. It can be complete. But “fulsome” suggests the opposite of sincerity: the apology so thick it sticks to the palate, the remorse so lavish you can smell the calculation beneath it. It is the language of the suitor who praises your “rare intellect” on the third date, or the lawyer whose “fulsome disclosure” is a thousand-page haystack designed to hide the needle.

Blame the lawyers first, as a matter of civic hygiene. The legal mind has a particular genius for turning language into a protective coating. Mediocre briefs are met with “fulsome praise.” Defeats are reframed as “fulsome engagement.” In every case, the word is a Soylent ooze, like gravy over a dry cut of meat.

Canadian government audits tout “fulsome overviews.” Osler, the law firm, offers “fulsome reviews of health and safety policies and procedures.”

One hears this ubiquitous word and pictures rhetoric inflated beyond its load-bearing capacity.

The etymology is instructive. Old English ful (full) became the 13th-century fulsum (copious), which by Shakespeare’s time had acquired its toxic edge. The anodyne modern usage is not Darwinian evolution; it is sloppiness dressed as sophistication.

What is to be done? Not much, except to be a little more Johnsonian. If you mean an apology that admits wrongdoing, say “unreserved.” If you mean a careful account, say “thorough.” If you mean someone has buttered you up insincerely, say “unctuous.” And if a prime minister apologizes for his footwear in fulsome terms, hear the sentence as Johnson would have: with the nose. Rank, odious, overdone.

Language is a moral instrument. When we allow words to be bleached of their meaning, especially their bite, we become easier to fool. Sunak’s apology to sneaker enthusiasts and Starmer’s spokesman’s praise for a forced mea culpa are not mere malapropisms. They are symptoms of a political culture that cannot speak plainly because it cannot think clearly.

The cure is simple: say what you mean. If you cannot, well, you know what to do.

The overuse and misuse of the word “fulsome” in political and legal discourse has diluted its original meaning, leading to insincerity and a lack of clarity. “Fulsome” has been hijacked to mean “fullness,” when its true definition implies something cloying, excessive, and offensive. This includes examples from Canadian and British politics, including the WE Charity controversy, Pierre Poilievre’s call for a “fulsome audit,” Rishi Sunak’s “fulsome apology” for wearing sneakers, and Sir Keir Starmer’s spokesman describing an apology as “fairly fulsome.” A return to precise language, advocating for words like “thorough” or “unreserved” instead of “fulsome,” ensures clear communication and prevents manipulation.

Why does the author argue against 'fulsome' investigations in politics?

What is the author's proposed alternative to 'fulsome' language in public discourse?

How does the author connect the misuse of 'fulsome' to a broader political issue?

Comments (0)