DeepDives is a bi-weekly essay series exploring key issues related to the economy. The goal of the series is to provide Hub readers with original analysis of the economic trends and ideas that are shaping this high-stakes moment for Canadian productivity, prosperity, and economic well-being. The series features the writing of leading academics, area experts, and policy practitioners.

The international system is undergoing a shift, creating fresh challenges for our economy. Prime Minister Carney recently called it a “rupture in the world order.”

This may be true globally, but the “rupture” in the Canadian economy started 10 years ago. After a lost decade of productivity stagnation and economic underperformance, punctuated by significant uncertainty, the case for fixing what we can control at home has never been stronger. As the prime minister often says: “We cannot control what other nations do. We can control what we give ourselves.”

While Trump’s tariff threats and geopolitical chaos create headwinds beyond our reach, Canada’s productivity crisis largely stems from domestic policy choices. Uncertainty from Washington makes it more critical that we get our own house in order. The convergence of external crisis and internal underperformance has opened the Overton window for reforms that seemed impossible just months ago.

What does this mean in practice? It means implementing a more competitive tax system that rewards investment and entrepreneurship. It means scaling back red tape and the administrative state that suffocates economic development. It means removing the barriers to competition in key sectors to break up protected oligopolies and invigorate dynamism. It means investing in the infrastructure that actually moves our economy forward. It means cleaning up the immigration system to prioritize quality human capital over sheer quantity. And it means bringing fiscal discipline and efficiency to government operations.

Each of these pillars reinforces the others. Together, they create the conditions for sustained productivity growth. This DeepDive sketches a blueprint to fortify Canada’s economic foundation.

The productivity problem

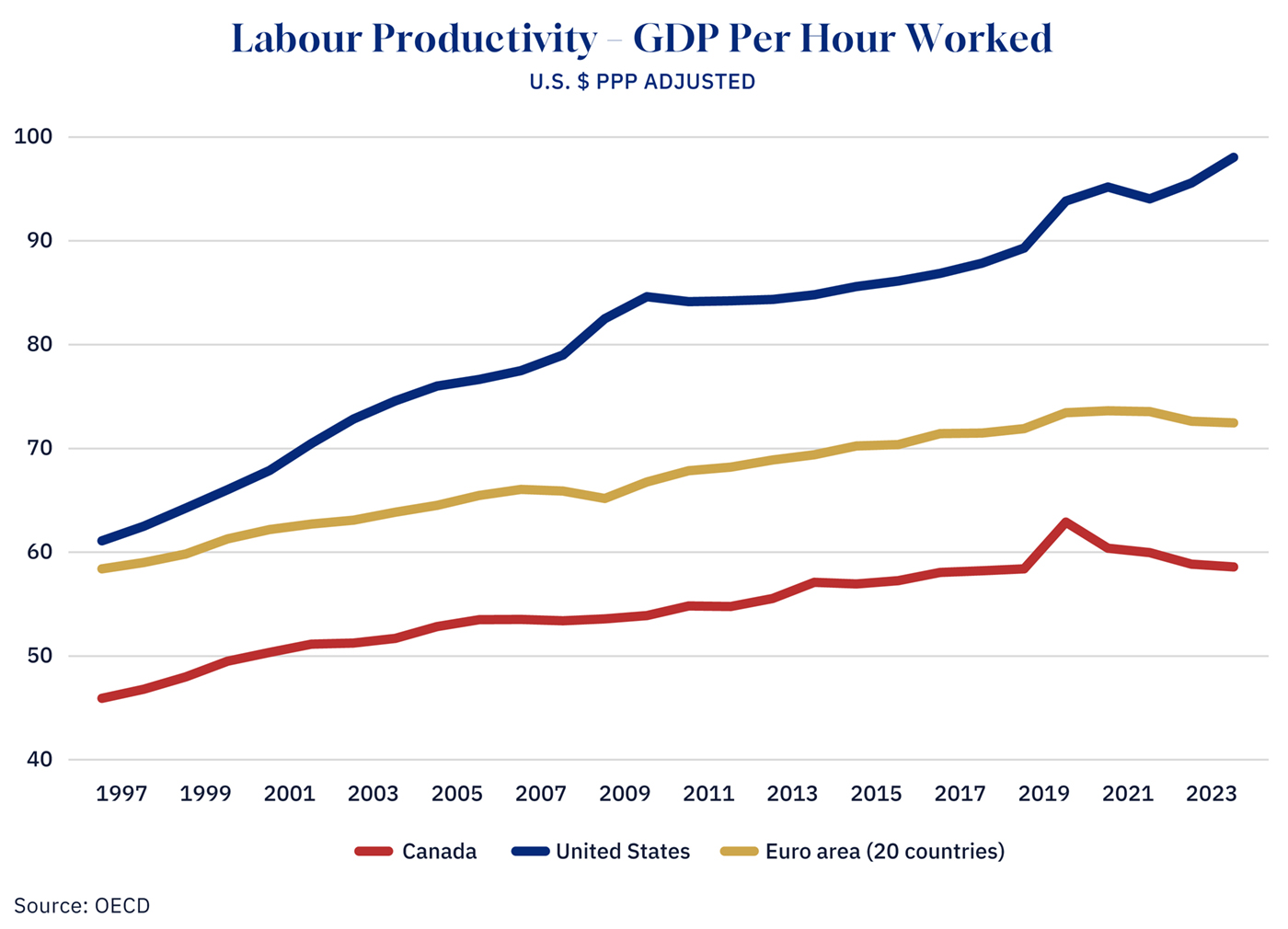

Canada’s productivity performance has been dismal. From 2014 to 2024, labour productivity barely grew, averaging just 0.3 percent annually, less than half the rate achieved in the previous decade (1 percent). The cumulative effect compounds each year, placing us further behind other nations. According to OECD data, Canada’s real GDP per hour worked in 2014 (in USD adjusted for purchasing power parity) was 67 percent of the level in the United States. That dropped to 60 percent by 2024.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Over the same period, the country has experienced what can be described as an investment crisis. Business investment per worker has been declining to the point that we now invest less per worker than most of our OECD peers. This investment deficit translates into lower productivity. Workers without modern equipment, updated technology, or adequate capital support simply cannot compete with their better-equipped counterparts abroad.

Stagnant productivity means declining living standards relative to our competitors, a shrinking economic pie, and reduced capacity to fund public services. The Bank of Canada called this a “break the glass” moment, and they’re right to sound the alarm.

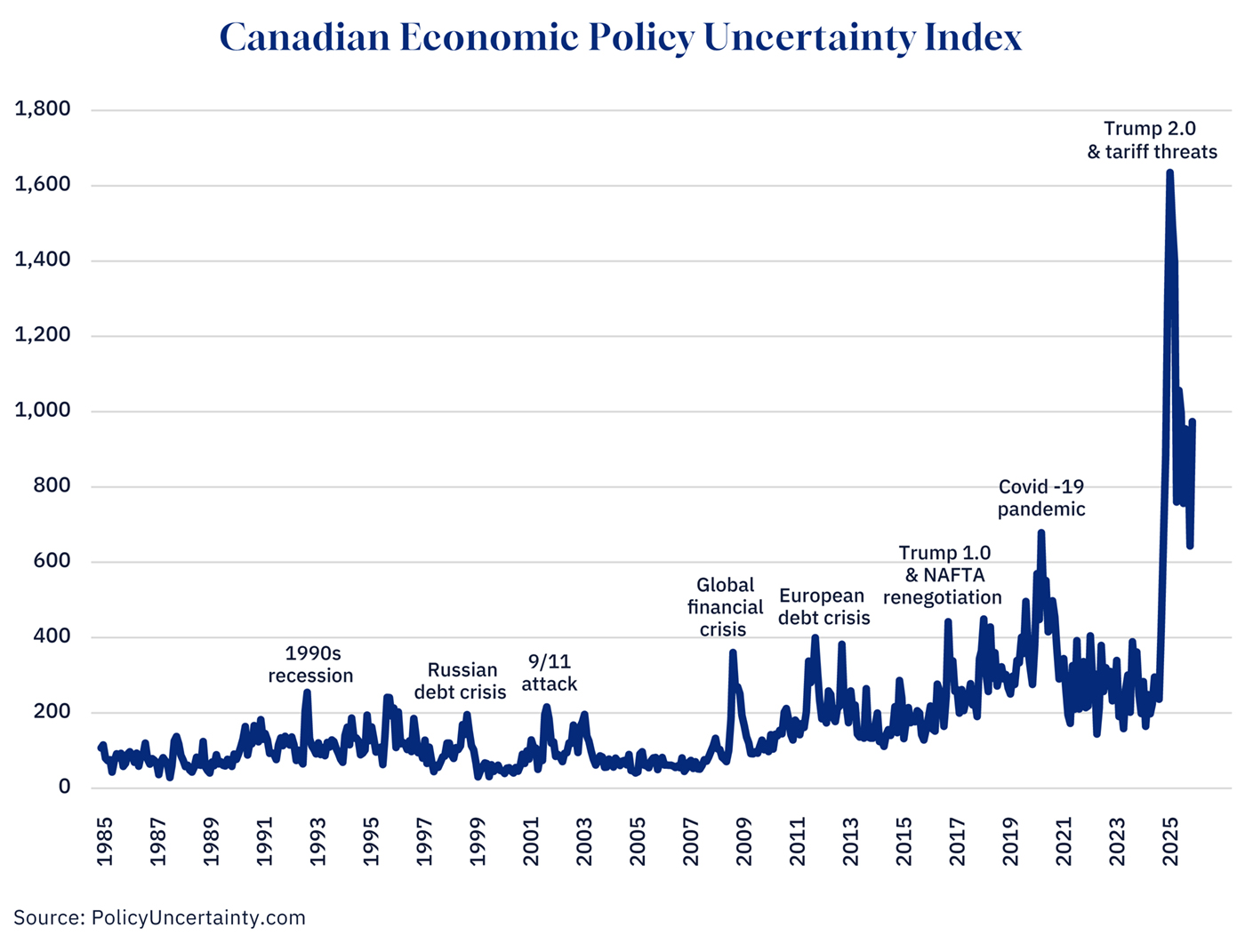

The challenge, which has built up over time, is now compounded by external factors. Trump’s tariff threats since his November 2024 election have created a new layer of uncertainty. Canada’s Economic Policy Uncertainty Index climbed sharply after the election and has remained elevated on a historical basis through January 2026 (the latest monthly data at the time of writing).

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

This uncertainty functions as an “invisible tax,” discouraging investment and ultimately hampering productivity and economic growth. When the rules keep changing, and the future remains murky, businesses hesitate to expand, new ventures are paused, and capital flows elsewhere.

We can’t control American trade policy. We can’t eliminate geopolitical uncertainty. But we can control our domestic policy environment. We can provide certainty where we have jurisdiction. That means committing to clear, stable, predictable policies across the reform pillars that follow.

Pillar one: Tax reform

Tax reform is a foundation, not a panacea. Canada urgently needs to clear away the disincentives that discourage and drive Canadian capital and talent elsewhere.

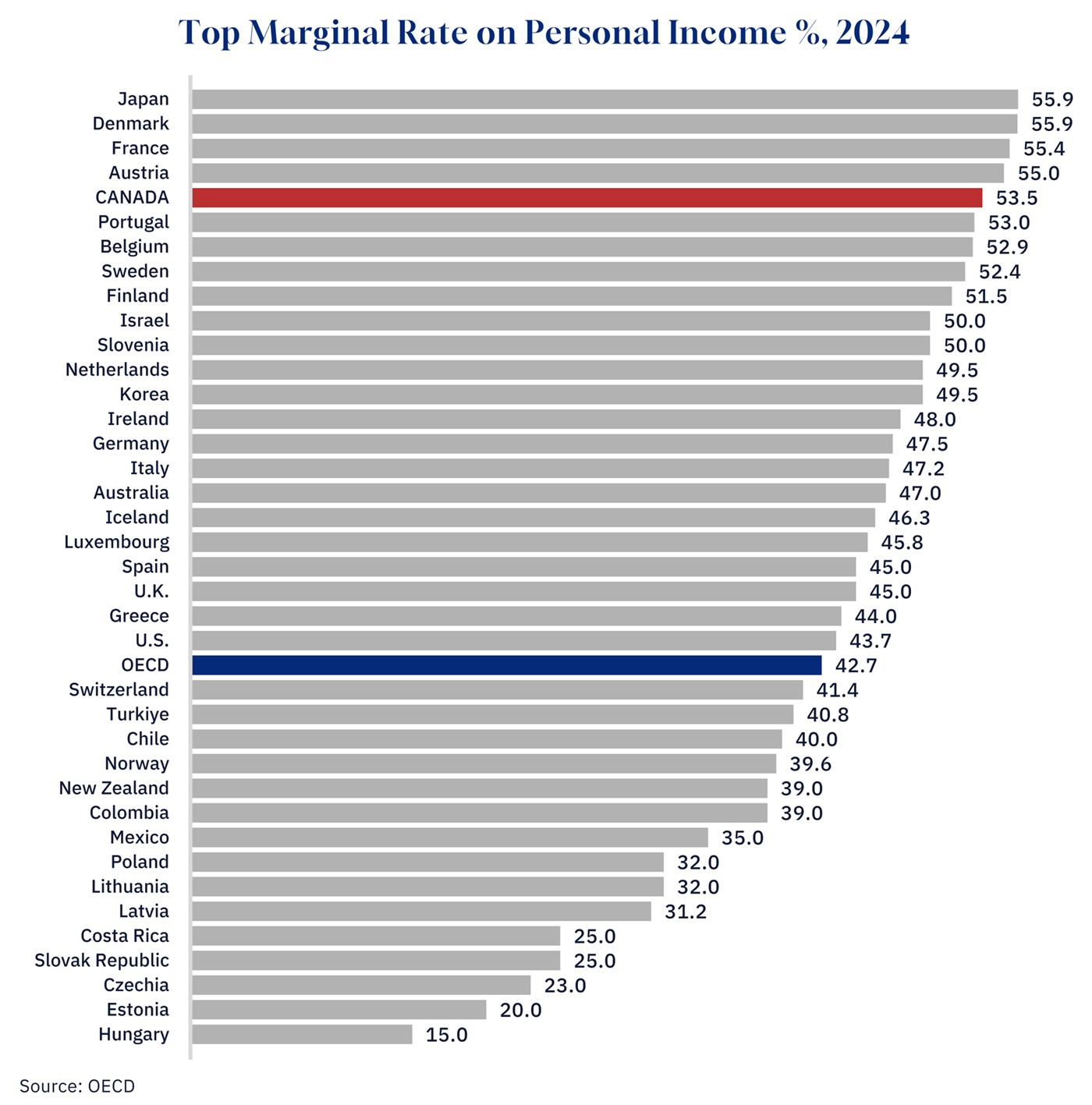

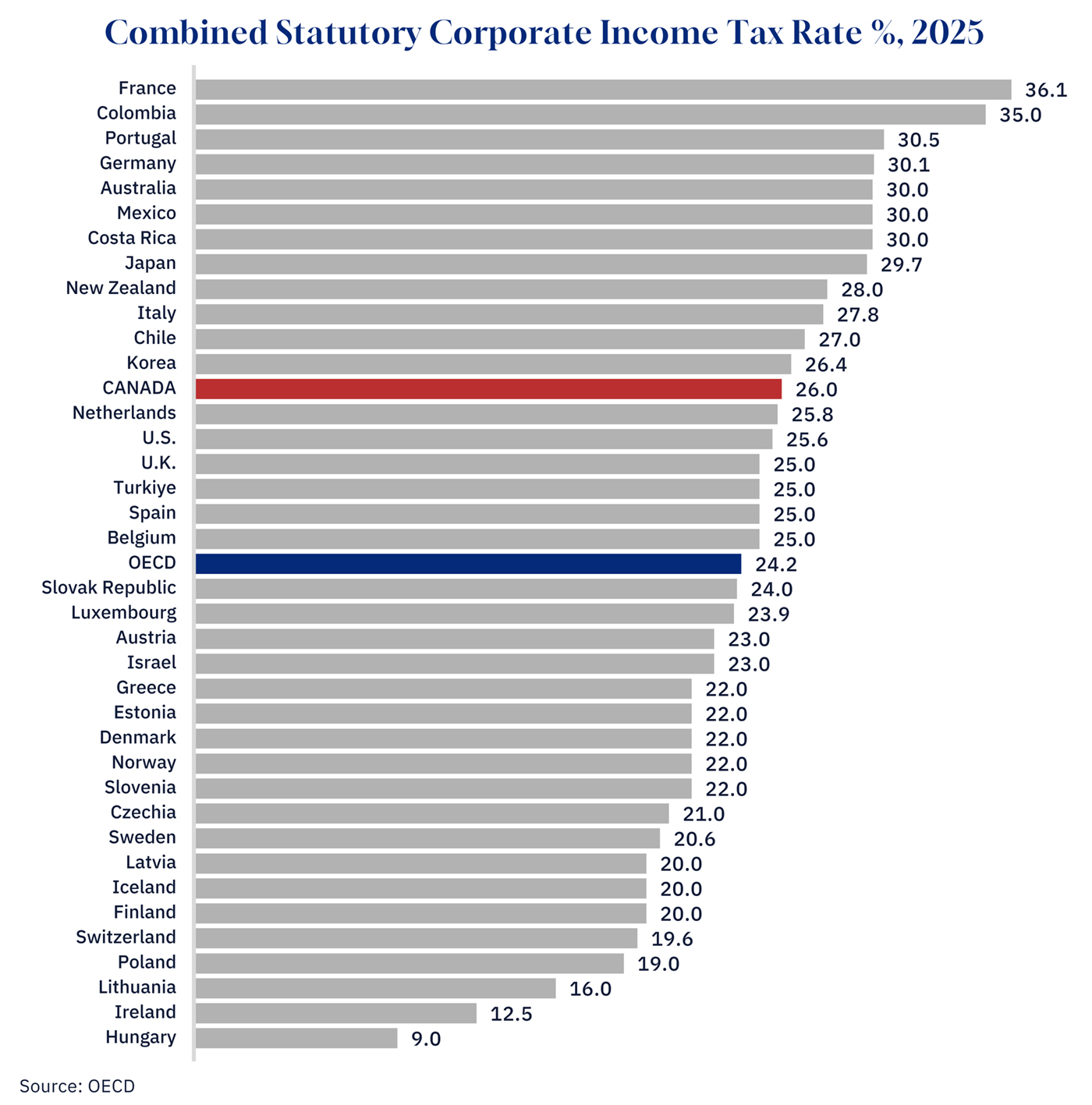

The case for fundamental tax reform rests on a simple observation: our current system punishes what we need to encourage. High marginal rates at relatively low income levels discourage work and talent. Uncompetitive and uneven corporate rates deter business investment and scaling. Punitive capital gains treatment locks in unproductive capital. Complexity rewards tax planning over productive activity. The cumulative effect makes Canada a less attractive place to deploy capital.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

My proposal for Big Bold Tax Reform addresses this by shifting incentives for businesses, along with major marginal rate reductions for individuals. A lower and uniform corporate tax rate makes Canada more competitive for capital. More generous treatment of capital investment encourages businesses to equip workers with better tools and technology, directly boosting productivity. Streamlined rules that reduce compliance costs free up resources for productive activity rather than tax planning.

But tax reform alone cannot solve our productivity crisis. If we fix the tax system but leave the rest of Canada’s structural straitjacket in place, we’ll simply have a more efficient way of doing very little. Big Bold Tax Reform is the foundation, but we need multiple pillars to fortify the complete structure.

Pillar two: Regulatory modernization

Excessive regulation imposes another “invisible tax,” estimated in Canada to cost small businesses alone $51.5 billion annually. Some have called tax and regulation the “silent killers” of competitiveness.

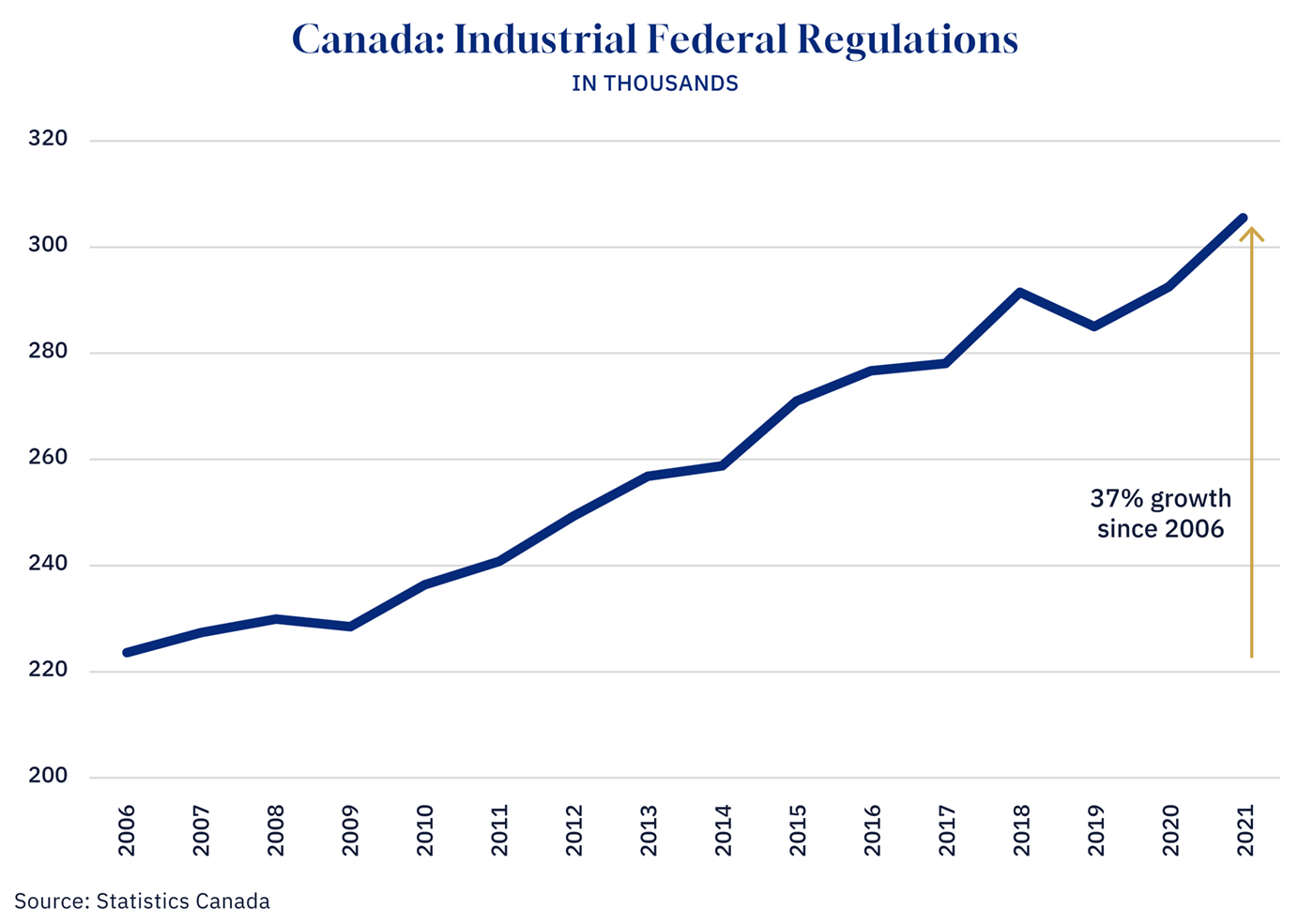

The empirical evidence supports this characterization. After studying the growth in federal industrial regulatory requirements from 2006 to 2021 (up 37 percent), Statistics Canada found a direct link to a 1.7 percentage point drop in GDP growth, along with declines in business investment, productivity, employment, and rates of business entry and exit.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

More broadly, the economic benefits of regulatory reform are well-documented. And the OECD’s latest economic outlook dedicated an entire chapter to the need for a regulatory reset, emphasizing that excessive regulation in network sectors hinders dynamism, innovation, and ultimately productivity.

Regulatory delays translate into capital sitting idle. General construction permits took nearly 250 days in Canada as of 2020 (the latest year of available data), three times longer than in the United States and among the longest in the developed world. Major mining project approvals stretch to 10-15 years compared to seven in Australia. When capital is mobile, delays kill deals. Projects that never get built represent productivity gains that never materialize.

The Carney government’s Major Projects Office promises to reduce federal timelines to two years for “national interest” projects. The federal government has also signed cooperation agreements with Ontario and other provinces under a “one project, one process, one decision” model to defer to provincial environmental assessment processes and reduce duplication.

The shift in tone toward investment and productivity represents a welcome departure from previous priorities, but the actual policies remain government-selected, contingent approaches rather than broad-based deregulation.

Projects must be referred to the MPO and designated by Cabinet based on opaque criteria. Some have noted that candidates are identified through a “cloaked process” without published evaluation standards. Even Prime Minister Carney cautioned that the referral “does not mean the project is approved.”

Canada needs universal regulatory certainty with equal application, including clear rules, strict timelines, and predictable outcomes for all projects meeting objective standards, not selective acceleration for politically favoured projects. International experience demonstrates that faster approvals, strong environmental protection, and Indigenous consultation are not mutually exclusive. The policy must be: get to yes or get to no, but get there fast.

We also need to remove all duplicative requirements across levels of government and scale back red tape that creates little to no value but imposes significant inefficiencies, driving up compliance and administration costs and dulling innovation and dynamism.

Pillar three: Competition policy reform

Put simply, our economy is a series of walled gardens that inhibit competition, dynamism, entrepreneurship, and innovation—the drivers of productivity.

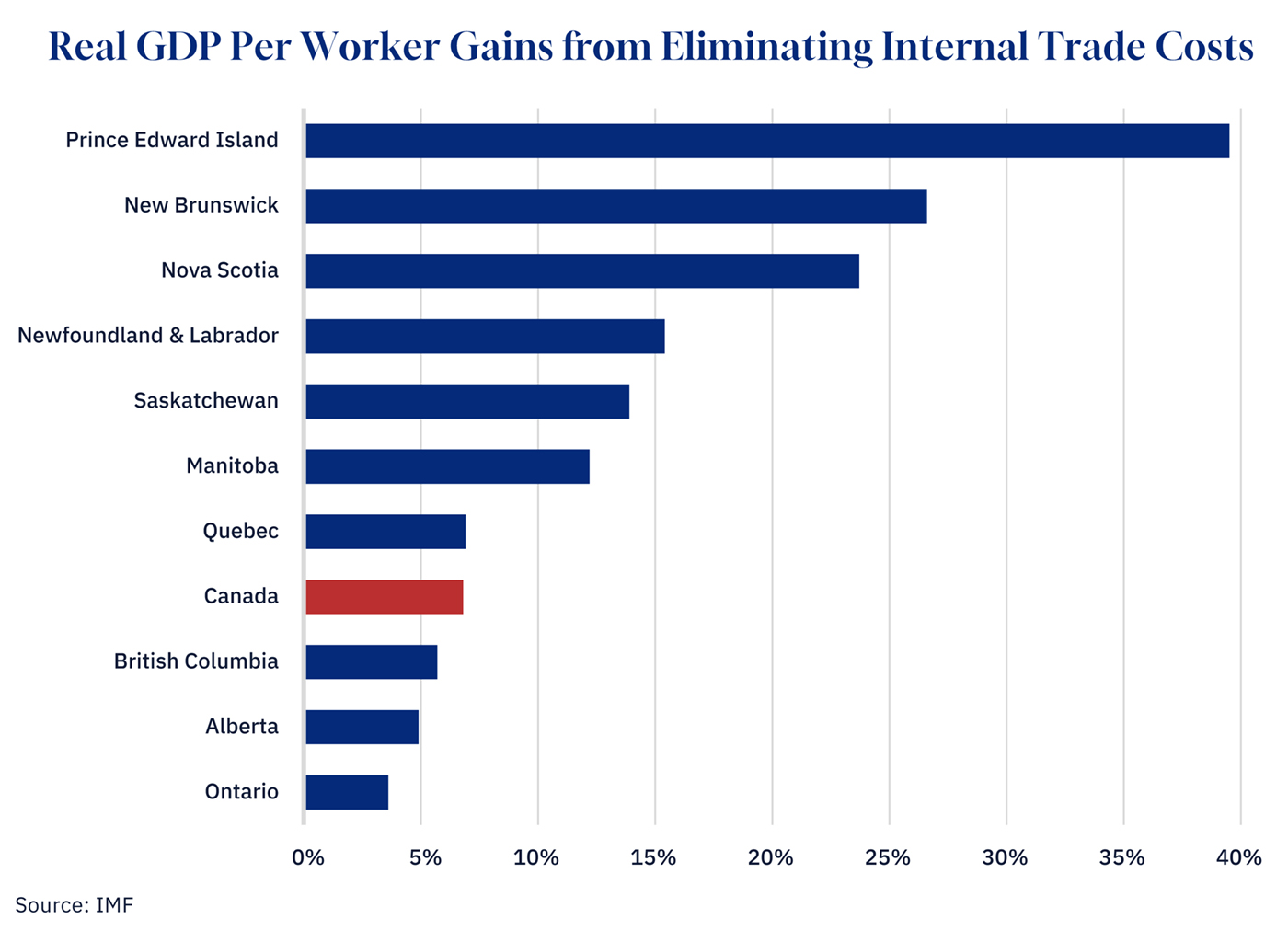

Interprovincial trade barriers act as internal tariffs, the equivalent of 9.5 percent nationally, according to the latest IMF estimates. Canada’s real GDP could increase by roughly 7 percent over the long run, or $210 billion in 2025, by fully eliminating internal trade barriers between the 13 provinces and territories.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

The infamous Comeau case confirmed that while we may be one country politically, we are often 13 separate markets economically. Progress is happening but remains slow, though Ontario and select provinces in December advanced mutual recognition on goods and services to unlock interprovincial trade.

Key sectors (telecom, banking, air travel, agriculture, groceries, professional services) continue to operate as protected oligopolies. The OECD has repeatedly pointed out that restrictions on services trade remain high in network sectors, hindering dynamism and innovation.

Competition drives productivity. As Bank of Canada Senior Deputy Governor Carolyn Rogers observed, competition forces firms to cut costs, innovate, and stand out. It also shifts resources toward the most efficient and growth-oriented businesses. When you’re protected from competition, you don’t need to innovate to survive. When you face real competitive pressure, you must find ways to produce more with less. That’s the essence of productivity growth.

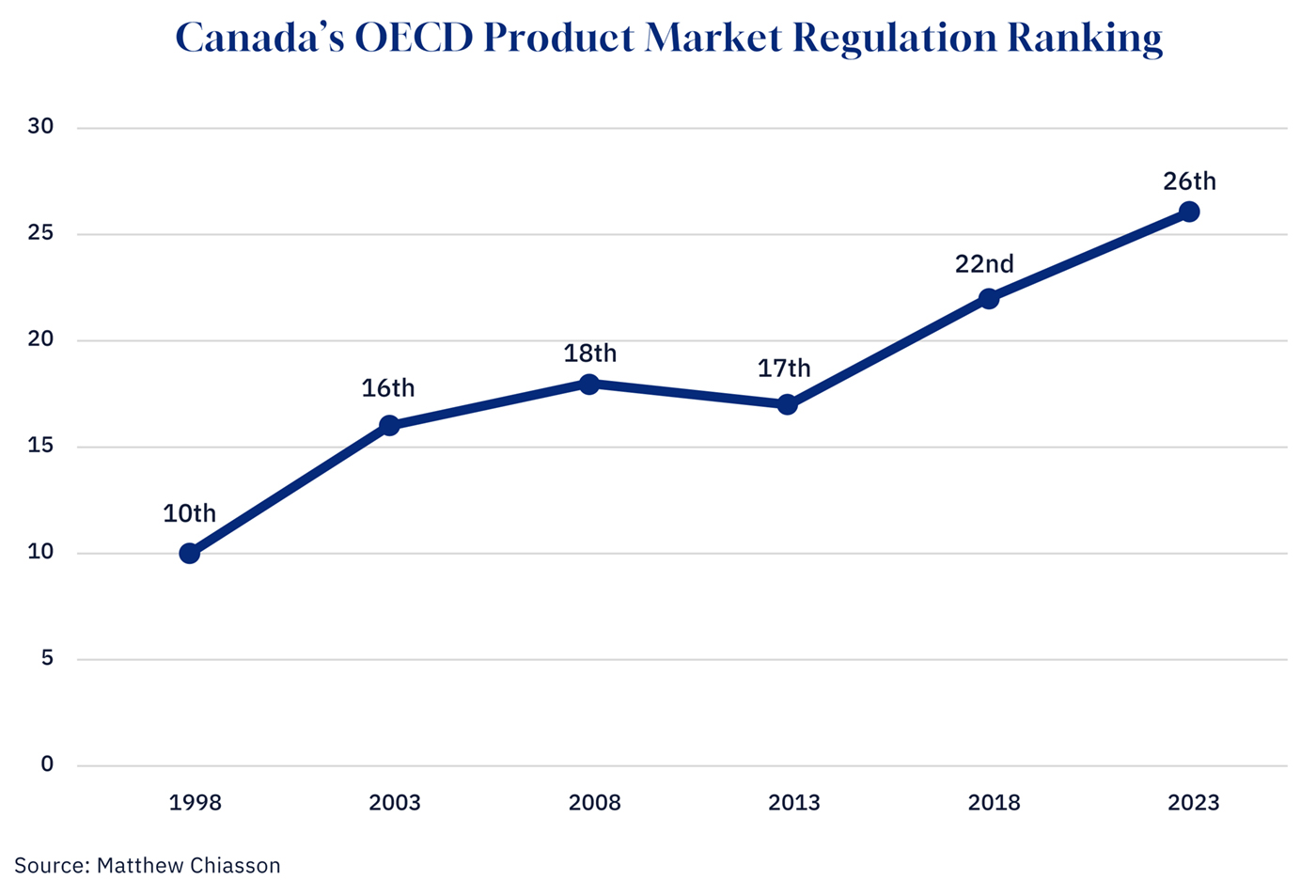

The data confirms how badly our competitive environment has deteriorated. Canada’s regulatory framework, as measured by the OECD’s Product Market Regulation indicators, ranked 10th most competition-friendly in 1998. By 2023, we had plummeted to 26th.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

This deterioration carries steep costs. A new Competition Bureau-commissioned study analyzing 15 OECD countries across 19 sectors over 25 years, estimates that aligning Canada’s regulations in four key sectors—energy, transport, retail distribution, and professional services—with best international practices could boost GDP by 6.5 to 10 percent over the long term. Anticompetitive regulations in these upstream sectors cascade through the economy, dampening productivity in downstream industries. These estimates are conservative, excluding gains from eliminating internal trade barriers and attracting greater foreign investment.

This regulatory drag shows up in Canada’s declining business dynamism. Business entry and exit rates have nearly halved over the past 40 years. When new firms can’t enter markets and challenge incumbents, the competitive pressure that drives productivity improvements disappears.

A recent Statistics Canada study found that increasing industrial concentration and declining entry rates dull firm investment, a leading cause of Canada’s weak productivity performance.

This insight builds on economist Joseph Schumpeter’s fundamental observation about “creative destruction,” the process through which innovation continuously revolutionizes economic structures from within, destroying old business models while creating new ones.

Last October, the Nobel Prize in Economics recognized three scholars whose work built directly on these insights. Canadian economist Peter Howitt of Brown University, alongside Joel Mokyr and Philippe Aghion, won for their research on how innovation drives economic growth and how new technologies replace older ones through creative destruction.

Their warning could not be timelier for Canada. As Rudyard Griffiths recently documented in The Hub, six of Canada’s top 10 companies by market capitalization are over a century old. When grouped together, our top 10 have been in business for more than a millennium, beating equivalent lists for the U.K., France, and Japan, and dwarfing their American counterparts.

View reader comments (0)

Compare this to America’s top 10, dominated by companies like Nvidia, Apple, and Amazon, firms born from the internet revolution and now the AI revolution. These are companies that didn’t exist 50 years ago. Many didn’t exist 25 years ago.

The rate of new business creation has also collapsed, with nearly half as many people launching businesses today compared to 20 years ago, according to a Business Development Bank of Canada study. This stagnation is compounded by a “brain drain” of our best talent; research from Leaders Fund reveals that fewer than one-third of Canadian-educated founders launch their ventures domestically, while nearly half leave to build their companies in the United States.

Even among those who stay, David Watt notes that the number of self-employed Canadians hiring employees is declining, with growth shifting toward sole proprietorships rather than job-creating enterprises.

The capital required to reverse these trends is also drying up: the latest RBCx report characterizes 2025 as the worst year for Canadian venture capital fundraising since 2016, with just over $2 billion raised, a bottleneck that threatens to starve the next generation of Canadian innovators.

The decline in business dynamism threatens future job creation, since small firms have historically been a key driver of job growth. While there has been much focus on big initiatives like the Major Projects Office, we also need to invigorate small and medium-sized enterprises and entrepreneurship, or there will be a weak foundation for sustained economic transformation.

Equally damning: Canada’s business R&D intensity has declined or stagnated at around 1 percent of GDP since 2000, remaining essentially flat while the OECD average climbed from 1.3 to 2.0 percent over the same period. As a result, Canada’s business R&D intensity has fallen from roughly 77 percent of the OECD average in 2000 to just 57 percent in 2023. Canada is falling further behind other OECD countries in the business R&D that drives innovation and productivity.

We need to build on recent momentum and completely eliminate internal trade barriers for goods and professional credentials. In parallel, we should review the Competition Act to explore whether the Competition Bureau needs greater power to block anti-competitive mergers and address abuse of market power by dominant firms.

More importantly, we must reduce product market regulations in sectors like telecommunications and air travel and ease foreign direct investment restrictions to encourage new entrants, investment, and productivity. Doing all this will force our incumbents to sweat. It will create the conditions for Schumpeter’s “perennial gale” to blow through the Canadian economy again.

Pillar four: Trade and transport infrastructure investment

Public infrastructure investment is crucial for long-term economic growth, addressing gaps, stimulating private sector activity, and boosting productivity. But it must be focused on foundational infrastructure. These investments are critical as Canada seeks to build resilience in light of tariff uncertainty, geopolitical shifts, and trade policy changes.

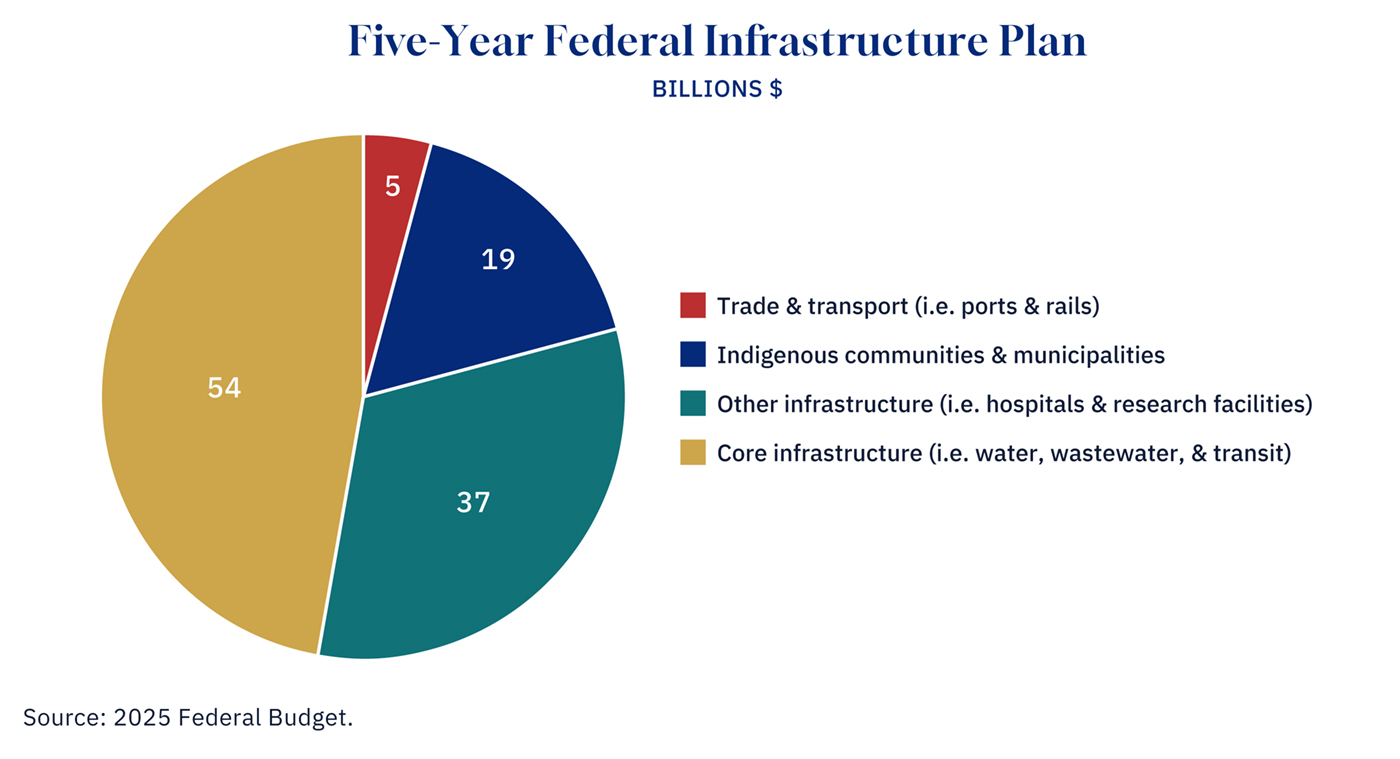

When we look at the federal government’s infrastructure plan unveiled in the November budget, very little of it will boost productivity and growth. The government touts a substantial $115 billion in planned “infrastructure investment” over five years. Yet only $5 billion of that amount (4 percent) is dedicated to trade and transport infrastructure, the critical arteries needed to diversify markets, build supply chain resilience, and actually drive productivity.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Better ports, railways, and highways reduce the time and cost of moving goods. This lowers input costs for businesses and expands market access. When transportation bottlenecks are removed, businesses can serve larger markets more efficiently, allowing them to capture economies of scale. Workers become more productive because the infrastructure supporting their work is more efficient.

We should prioritize public investments in trade corridors (ports, railways, energy grids) to diversify exports and reduce dependence on a single trading partner. Roads and highways that reduce congestion are equally vital for moving people and goods efficiently. These infrastructure investments can help lower transportation costs, improve supply chain efficiency, and open new markets.

Instead of sector-specific subsidies protecting inefficient firms, we should direct public funds toward infrastructure that all businesses can use, fostering broad-based growth and competition. We need to invest in the ports, rail corridors, roads, and energy grids required to get our goods to market. The bottleneck in our economy is physical as much as fiscal. If we cannot move our resources and products efficiently, tax and regulatory reform won’t save us.

Pillar five: Immigration reform

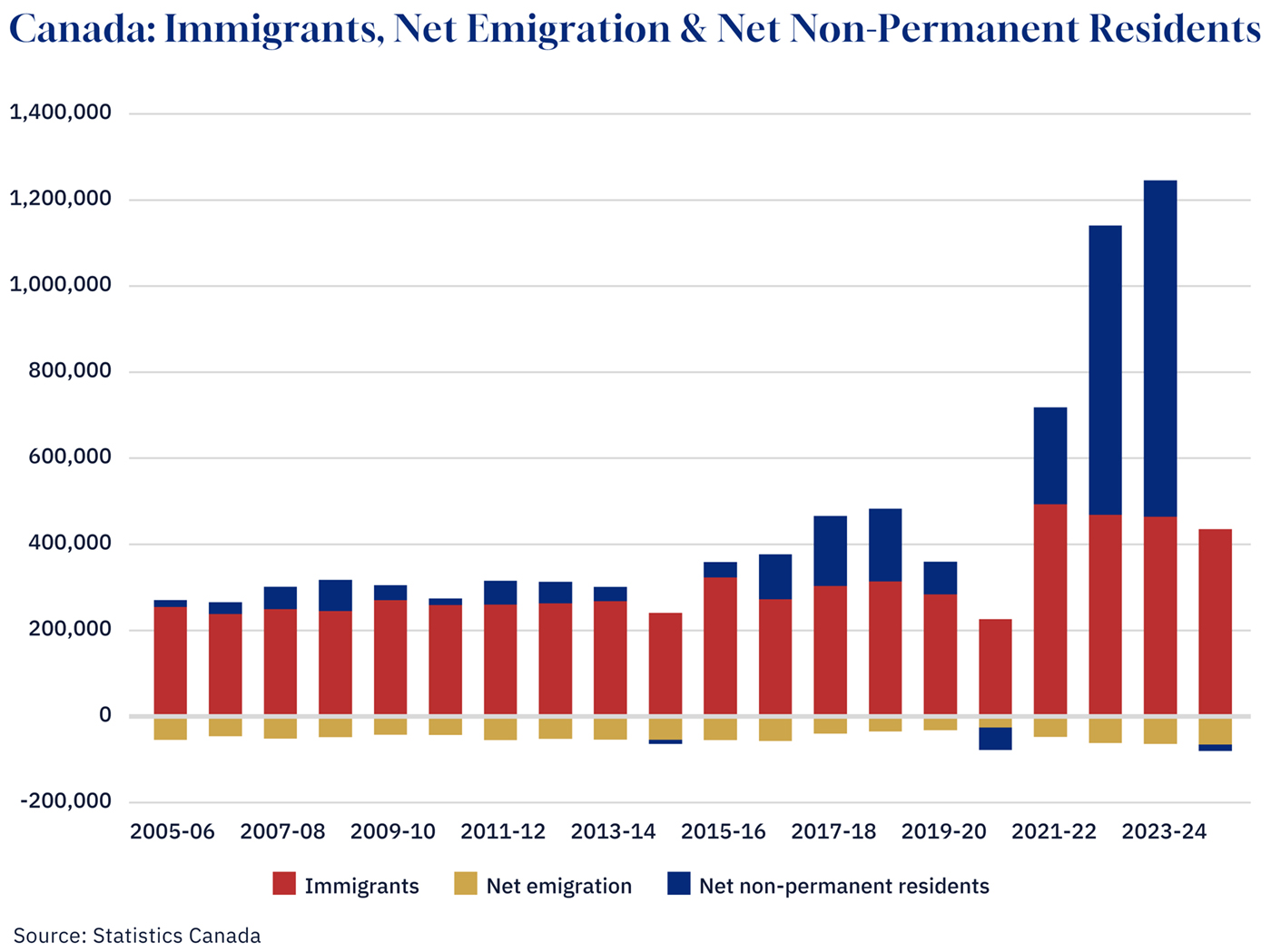

We need to realign our demographics with our economics. Immigration policy under the Trudeau government saw a massive surge in numbers and drifted toward utilizing low-skilled temporary labour to plug gaps in low-wage sectors. The influx reduced incentives to invest in automation by making cheap labour readily available. And the sheer volume of population growth also strained housing and public services such as health care, education, and infrastructure.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

When businesses can easily access low-wage labour, they have less incentive to invest in the capital equipment and technology that make workers more productive. Why buy a machine when you can hire someone cheaply to do the work? This substitution of labour for capital directly undermines productivity growth. Meanwhile, high-skilled immigrants who could complement capital investment and drive innovation were crowded out by the emphasis on temporary, low-skilled workers.

The system’s lack of integrity compounds these productivity challenges. With possibly over half a million migrants unlawfully present and a 38 percent missing rate for non-permanent residents (2021 census), businesses face profound uncertainty in workforce planning. Companies cannot make sound capital investment decisions when they don’t know the actual size or skill composition of the available labour pool. This uncertainty further discourages the productivity-enhancing investments Canada desperately needs.

Dialling back immigration targets for both permanent and temporary residents acknowledges that managing recent rapid population growth is necessary. But the new numbers for permanent resident admissions stabilize at 380,000 per year, keeping the permanent stream of immigration well above pre-Trudeau government levels of approximately 260,000. On top of these baseline targets, the federal government has introduced “one-off” measures to transition roughly 150,000 existing temporary residents to permanent status over the next two years.

While the target reductions address the quantity of new arrivals, a critical issue remains unaddressed: the mix. The system, emphasizing low-skilled non-permanent residents, shifted focus away from prioritizing higher human capital. If most temporary residents already in Canada transition to permanent status rather than leave, this will perpetuate the skill-mix problem and make the shift to high-skilled immigration more difficult.

We need to recalibrate our immigration system to better support long-term growth and innovation. This means adjusting immigration levels by reducing total residents to a level aligning with Canada’s absorptive capacity. We must prioritize human capital by shifting policy focus from low-skilled temporary workers to high-skilled permanent residents, increasing human capital intensity to foster innovation and boost productivity. We need a pivot back to high-human-capital immigration, prioritizing engineers, scientists, and entrepreneurs who complement capital investment rather than substituting for it.

The Carney government has acknowledged the problem and taken steps to reduce intake levels. But more work remains to fundamentally restore the system’s integrity and reorient it toward human capital intensity to ensure immigration policy supports rather than undermines productivity growth.

Pillar six: Public sector reform and fiscal certainty

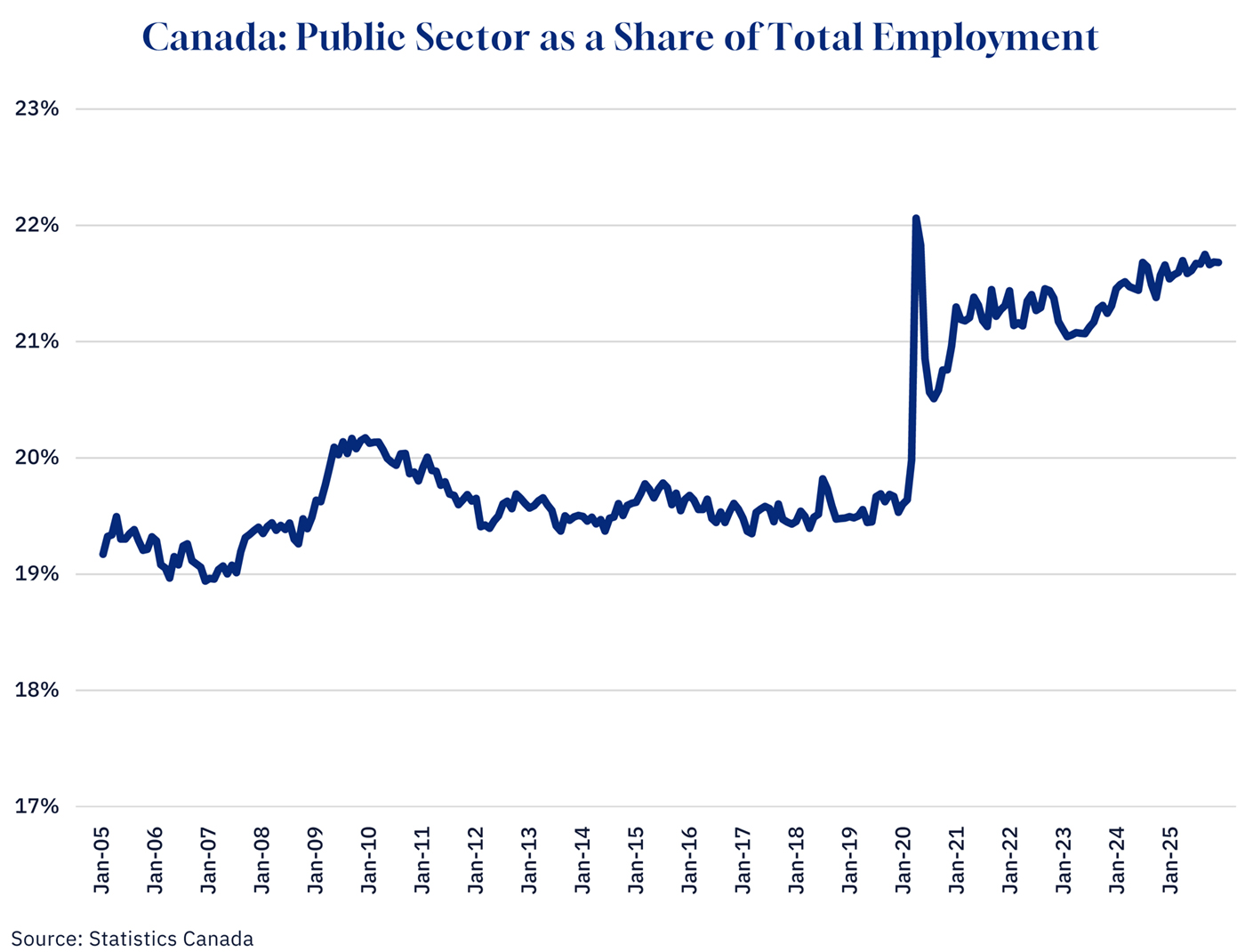

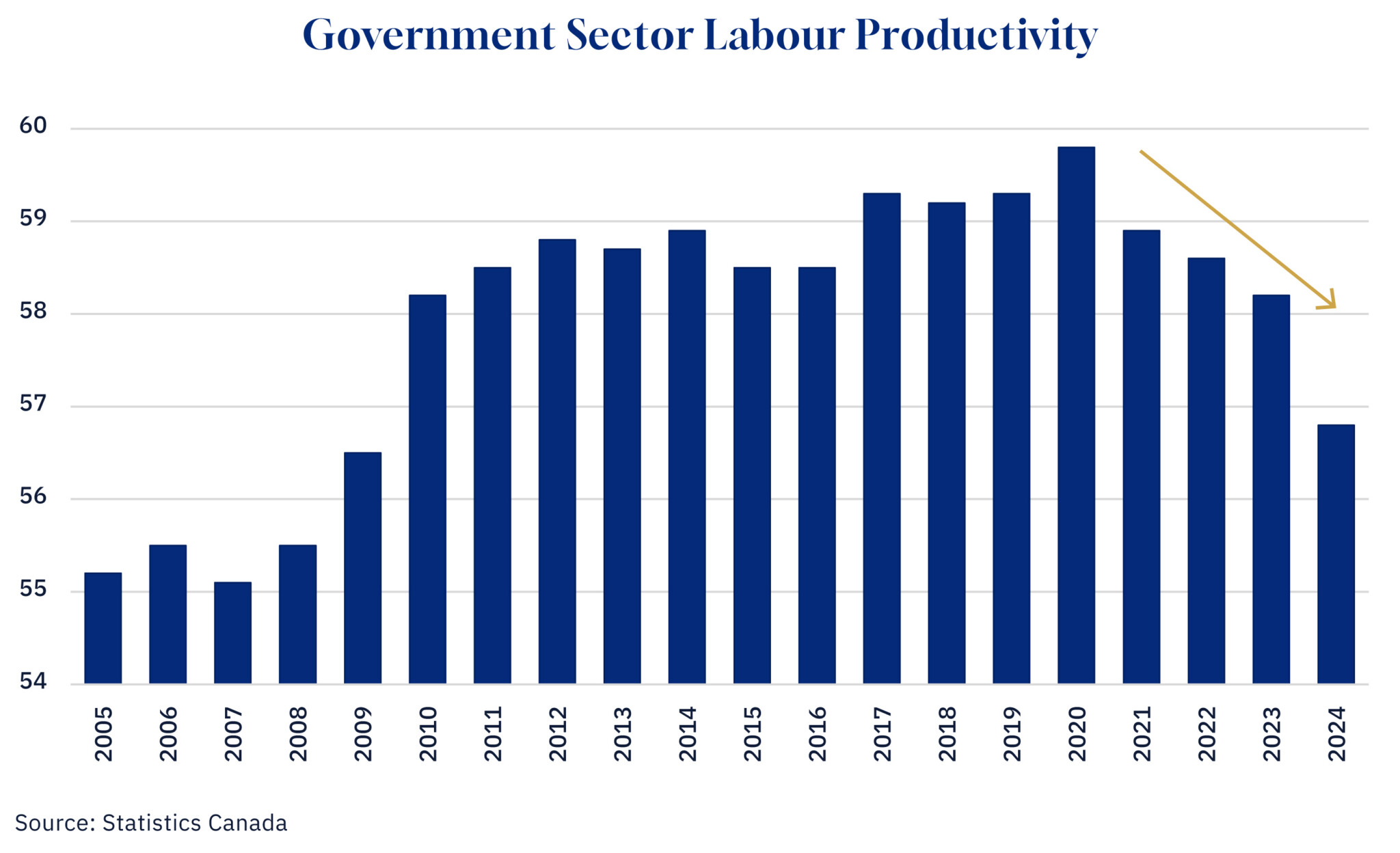

Finally, we must address the “government gap.” A recent study highlights a diverging trend where the government sector is growing in size but declining in productivity. We cannot afford a bloated, inefficient state apparatus acting as a drag on the productive economy. Administrative efficiency is about boosting productivity and restoring state capacity to deliver essential services without crowding out private activity.

The scale of the challenge is substantial. Twenty years ago, the public sector accounted for approximately 19 percent of Canada’s employed workforce. By the end of 2025, government employees at all levels comprised 21.7 percent, with a marked expansion starting in 2020. These figures exclude contract workers, meaning the true scale of government employment is even larger.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

The federal numbers, in particular, tell a stark story. The federal public service grew by over 110,000 employees (from about 257,000 to 368,000) between 2015 and 2024. The Carney government plans to reduce the headcount by an estimated 40,000 workers through measures like attrition. While necessary, this adjustment (approximately 10 percent of the peak workforce) represents a slow scaling back from an unsustainable hiring spree, not a paradigm shift in civil service efficiency.

An expanding public sector draws resources from the private sector, which is where productivity growth primarily occurs. Government productivity itself has lagged, meaning we’re getting less output per tax dollar spent. This matters for the broader economy because higher government spending must eventually be funded through higher taxes on the productive sector, creating a drag on private investment and growth.

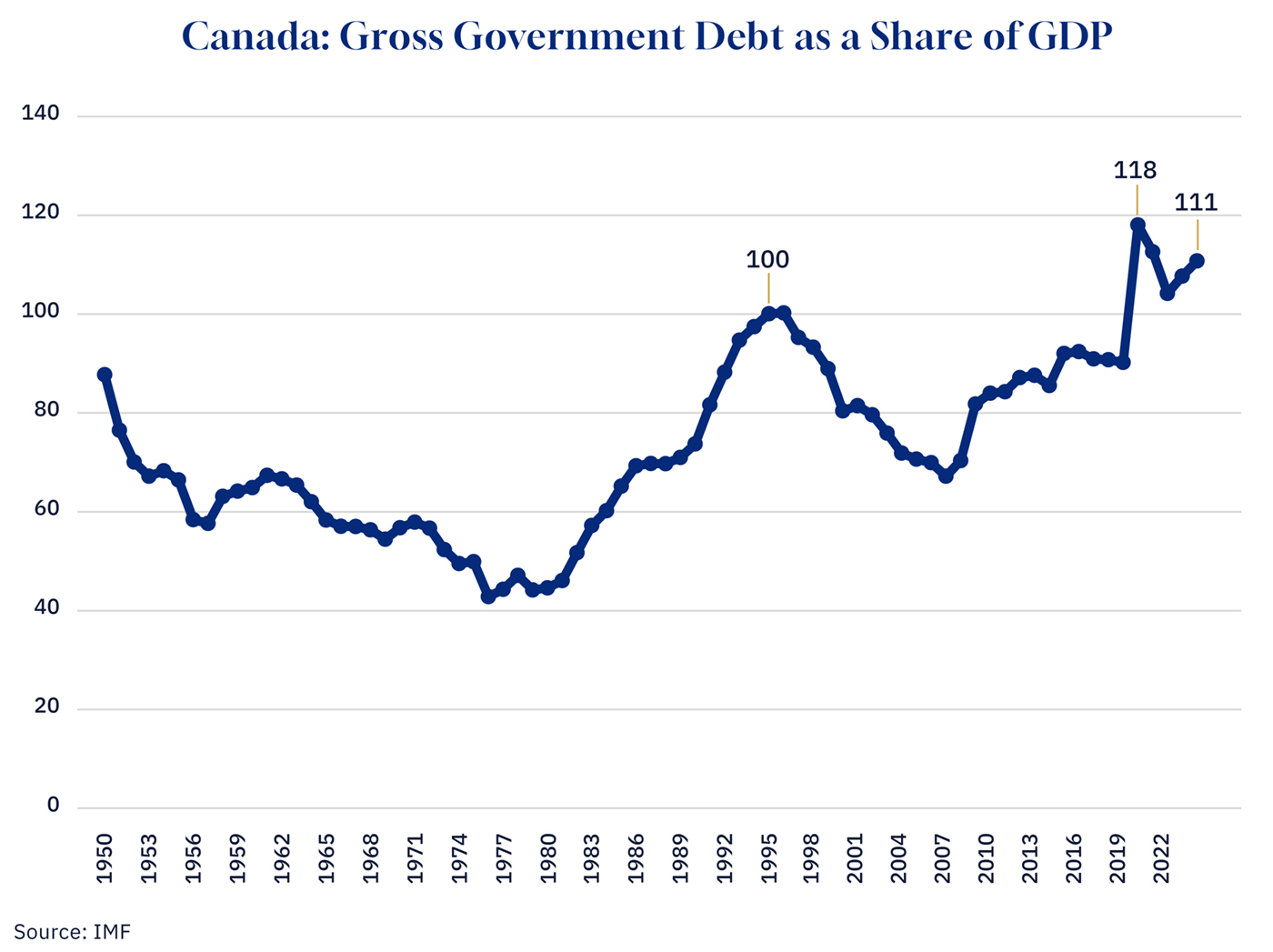

This connects to a broader imperative: fiscal certainty. Collective government gross debt in Canada has risen since 2007. This steady accumulation creates its own form of uncertainty, as businesses and investors reasonably worry about future tax increases needed to service growing obligations. Fiscal prudence matters not just for government balance sheets but for the investment climate. When businesses fear higher taxes tomorrow to pay for today’s deficits, they invest less today.

Graphic Credit: Janice Nelson.

Scaling back federal public sector personnel to sustainable levels that the private sector can support, while maintaining essential services, is part of this puzzle. So is committing to credible fiscal frameworks that provide certainty about the tax and spending trajectory.

Sound public finances and productivity growth are mutually reinforcing, as Scotiabank Economics demonstrates. Higher productivity means higher wages and income tax revenues, and more profitable businesses mean higher corporate tax revenues.

What it will take

Breaking the cycle of low investment and weak productivity requires comprehensive reform across all six pillars simultaneously. Tax reform without regulatory modernization leaves capital trapped by red tape. Competition policy without infrastructure investment creates demand we cannot supply. Immigration reform without a growth-oriented tax system deepens our productivity gap. One-off measures and selective interventions won’t cut it.

We cannot control Trump’s tariffs or global chaos, but we can control our own policies. The choice is between continuing to protect incumbents and punishing innovators, or building an economy strong enough to handle whatever external shocks come next.

This agenda goes after sacred cows. It challenges corporate giants enjoying protected markets. It threatens bureaucracies that have grown comfortable. It requires honest conversations about immigration that politicians would rather avoid. It asks public sector workers to do more with less. Every pillar will face pushback from powerful interests with everything to lose from reform.

But with crisis comes opportunity. External pressures have created unusual political space for bold action. Leaders at all levels of government now have license to pursue reforms that would have seemed impossible in calmer times. The question is whether they’ll seize this moment or let it pass.

Canada’s economic future hinges on addressing internal weaknesses amid global uncertainty. There are six key pillars for reform: tax reform, regulatory modernization, competition policy reform, trade and transport infrastructure investment, immigration reform, and public sector reform. Canada’s productivity has stagnated, lagging behind other nations, exacerbated by external factors like U.S. trade policies. Canada needs comprehensive, simultaneous reforms across all pillars to unlock productivity growth and build a resilient economy.

The article identifies 6 pillars to secure Canada's economic future. Which pillar do you think is most crucial and why?

How does the article suggest Canada's immigration policy is hindering productivity, and what changes are proposed?

The author mentions 'external shocks' and 'domestic policy choices'. Which does the article suggest is more responsible for Canada's economic underperformance?

Comments (0)