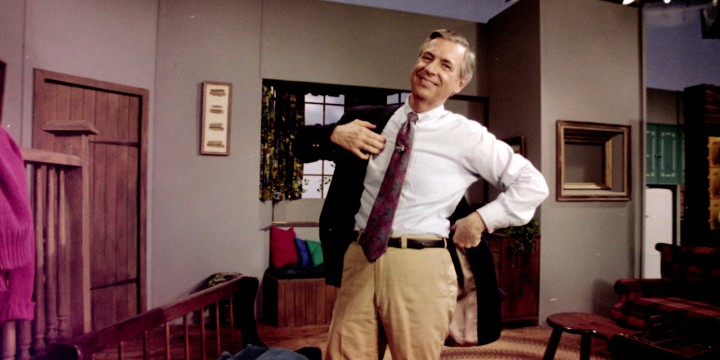

Why Mister Rogers still matters today: Gregg Behr and Ryan Rydzewski on his enduring lessons for raising kids

This episode of Hub Dialogues features host Sean Speer in conversation with child advocate Gregg Behr and award-winning writer Ryan Rydzewski about their poignant book, When You Wonder, You’re Learning: Mister Rogers’ Enduring Lessons for Raising Creative, Curious, Caring Kids.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, or YouTube. The episodes are generously supported by The Ira Gluskin And Maxine Granovsky Gluskin Charitable Foundation and The Linda Frum & Howard Sokolowski Charitable Foundation.

SEAN SPEER: Welcome to Hub Dialogues. I’m your host, Sean Speer, editor-at-large at The Hub. I’m honoured to be joined today by Gregg Behr, a father, child advocate, and director for The Grable Foundation, and Ryan Rydzewski, a science and education writer who’ve come together on a must-read book entitled, When You Wonder, You’re Learning: Mister Rogers’ Enduring Lessons for Raising Creative, Curious, Caring Kids. I’m grateful to speak with them about Mister Rogers’ philosophy of child development and how it can serve as an ongoing blueprint for happier, healthy kids. Gregg and Ryan, thanks for joining us at Hub Dialogues, and congratulations on the book.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Thanks so much for having us, Sean. We’re thrilled to be here.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s start with Fred Rogers as a cultural phenomenon, particularly for our younger listeners. Help us understand the significance of Fred Rogers and his neighbourhood. When did the show start? How many years did it run? Do we have a sense of how ubiquitous it was in terms of distribution across the United States and so on? What was the cultural significance for those like you who grew up in Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Yeah, so I could tell you a little bit about how the Neighborhood got started. Fred Rogers was a—he was actually a minister, or he was going into the ministry, and he walked into his parents’ living room in the 1940s and a little town called Latrobe, Pennsylvania, which is not far from where we are in Pittsburgh. And there he encountered his first television. And he hated what he saw when he turned it on. The first thing he saw was people throwing pies in each other’s faces. And he used to talk about how he hated to see people demeaning one another using technology. He decided he wanted to use that technology in a way that was attractive to kids, and he was going to use it to minister, in fact, to children. And so he became a puppeteer, working at a community television station here in Pittsburgh called WQED.

And he did that for a couple years before he got an invitation to actually go up to Toronto from Pittsburgh. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation called him up and they offered him a 15-minute block of time, which was the first time he ever had a television program named after himself. It was called Misterogers, just one word. It’s also the first time he ever was in front of the camera. He’d always been behind the scenes before that. And that’s really where he honed his sort of style. He stayed in Canada for, I think it was six or seven years doing the Misterogers show before he came back to Pittsburgh and ultimately built what came to be known as Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.

And in that incarnation it ran from 1968 to 2001. And it would be really hard to overstate its cultural impact here in the United States. I sometimes like to say that there’s no one else who I can think of who, when we talk about him, we have to emphasize the fact that he wasn’t a saint, that he was just a regular guy. Generations of people grew up watching Fred Rogers. And now, with a recent movie starring Tom Hanks and a brilliant documentary by Morgan Neville, and an animated spinoff called Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, Fred Rogers is just as much a part of our culture as he was when he was alive.

SEAN SPEER: Yeah. We’ll come to the Rogers resurgence that we’ve seen through some of the films and spinoffs that you mentioned, but before we get there, Ryan and Gregg, how would you capture Fred Rogers’ philosophy of child development and where did it come from?

GREGG BEHR: It came from science, and that’s partly why Ryan and I wanted to write this book, to represent Fred Rogers not just as that loving host that we experienced on our television ourselves as kids growing up here in western Pennsylvania, in Mister Rogers real-life neighbourhoods, but we want to tell him about his work as a learning scientist who was decades ahead of his time. So Ryan mentioned that Fred studied at the Pittsburgh Theological Seminary, and it was his teachers there who said, “Fred, if you want to get involved in children’s multimedia and some of these other practices, you better learn something about child development theory and practice.” And that’s how Fred ended up at a place called the Arsenal Family and Children’s Centre here in Pittsburgh. Now, this is where the story gets incredibly interesting because there was a remarkable coincidence of people who were at this place called Arsenal.

There was Benjamin Spock, the doctor whose book Baby and Childcare is one of the best-selling books of all time. There was Eric Erickson. There were others like Brazelton, the pediatrician, and others who were coming through Arsenal. And most importantly for us and for Fred’s story, there was Margaret McFarland, a psychiatrist at the University of Pittsburgh, who became Fred’s lifelong mentor and dear friend. Now, we mentioned that to say that you could imagine Fred in this setting absorbed all of this science, this cutting-edge Mount Rushmore of 20th-century child development theory and practice, and he applied it in the most seamless of ways through puppetry and lyrics and wardrobe and a physical set itself. It’s incredible when, as adults, we look back and go beyond the emotional connection we had to see how it is that Fred did what he did and to appreciate how much it was grounded in what today we would call the learning sciences—not a phrase that was used 40 and 50 years ago.

And when we talk about Fred and his methods, we now like to talk about it as the Fred Method. But again, two phrases that weren’t used during Fred’s time: old child; learning sciences. If there’s a simple equation that conveys Fred and his philosophy and what he was creating, it was the sense of the academic, social, and cognitive growth that every child experiences in whole-child development, along with all that we’re learning about learning itself through the learning sciences. Whole Child plus learning sciences equals the Fred Method.

SEAN SPEER: Wow, what a great answer, Greg. Just so much insight there. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t want to diminish the importance of science and its underpinnings for Fred’s philosophy and how it manifested itself on the program, but you also talked about his human touch. How did that diverge from the norms of the era, including, for instance, male expressions of emotions like love, kindness, and vulnerability? How was that ultimately part of his conception of reaching the whole child?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Yeah, I think if there was one message at the core of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, it was, “I like you just the way you are.” Fred used to say that in all sorts of different ways. He would sing it in his songs, he would tell us at the end of each episode. And when Fred said that—a seemingly simple phrase—there is a lot wrapped up in that. If somebody likes you just the way you are, that means they accept you with all of your big feelings, positive and negative. That means they accept you with all of your flaws, all of your shortcomings, and all of your joys and your strengths. Fred used to say that it’s important to love and accept someone right now exactly as they are, not for what he or she will be, but exactly as they are right now.

And that’s not always easy, right? Fred used to say that love is an active noun; it’s an active noun like struggle. And I think what we saw in the neighbourhood was a daily practice of Fred showing what it means to like someone just the way they are right now—as they are exactly. And we saw what that can do; we saw what it did for the characters in the show, and we felt what it can do for ourselves as viewers to be told day in, day out that someone out there likes you just the way that you are. There is all sorts of science, as Gregg mentioned now, that shows that when people feel that way, their academic outcomes improve, they actually end up in jobs making more money, they’re more likely to vote, they’re even healthier physically. So that one simple phrase, “I like you just the way you are,” conveyed a whole lot, and it presented some measurable, tangible benefits for millions of kids over decades on the air.

GREGG BEHR: And Sean, just think about how incongruous Fred was for his time. I mean, it’s crazy to think about in a 2023 context, but if we go back to the ’70s when I was a kid watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood alongside my brother, oftentimes with my mom in the living room, what were our alternatives? There were other great children’s television shows like Captain Kangaroo and superheroes in the Hall of Justice, but there was something uniquely different about Fred and the slowness and deliberate approach that he took.

And to your point, it is talking about big things. I mean, it’s just nuts to think about, in today’s context, a children’s television host taking on issues of race or war or assassination, or the things that we as kids wondered about. He made it possible. He recognized our big, crazy feelings and invited us in. And it’s why today, as Ryan and I have the privilege of travelling through America and through Canada, the stories that people have about the connection to Fred Rogers—and oftentimes, I was alone in my house, and I turned on that television show, and I felt a connection, and I knew there was a caring human being on the other side of my television screen. He did something magical in that television exchange that we experienced.

SEAN SPEER: As you both have alluded, Rogers was a Christian, and though he was a true pluralist, he was probably more outwardly religious than many might be accustomed to in today’s era. How did Fred Rogers’ religious values and personal theology influence him? How did he balance living out who he was without risking turning people off or creating a space that wasn’t perceived as inclusive?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Sure. So yeah, you’re right. Fred was an ordained Presbyterian minister. He was a pluralist in the sense that he studied all sorts of religions. He really got to the universal heart of several of those religions, which is love, right? It’s love, it’s acceptance, it’s taking care of your fellow man. But I think if there’s one phrase that expresses Fred’s theology, it was a quote that he actually loved himself, of course, attributed to St. Francis of Assisi, and that’s “preach the gospel at all times, if necessary, use words.” So in many ways, the Neighborhood was Fred’s ministry, but Fred was not—he didn’t talk about God. He didn’t talk about being a Presbyterian minister. He didn’t talk about Catholicism on the air.

Instead, Fred was a living example of what he stood for, of what he believed in. In the foreword to our book, which was written by Fred’s now late wife, Joanne, she wrote that no one worked harder at being Fred Rogers than Fred Rogers himself. So we like to say that the Fred you saw on screen, it wasn’t an act. The Fred you saw on screen was the Fred you’d see on the street, walking down the street in Pittsburgh. But it was a practice. Fred was a practicing minister. Fred knew that he had to lead, he had to live by example. And that’s exactly what he did. I think that’s why we’re still so in awe of him in so many ways today.

GREGG BEHR: He often talked about the sacred space, right? The sacred space of that screen and the child that’s on the other side of that screen to whom I’m filming. I think that expresses a remarkable sensibility of his grounding in his religious studies and creating an atmosphere that was grounded in goodness. In fact, at the turn of the millennium when a journalist turned to Fred and said, “What’s the greatest challenge facing humanity?” You could think of a thousand things he might have said. And in a really profound moment, he said, “Make goodness attractive.” That sensibility that is indisputably grounded in his theological training and one grounded in goodness and an expression of goodness, and making goodness real in this world.

SEAN SPEER: Ryan, I’m so grateful that you referred to that beautiful quote from the foreword: “No one worked harder at being Fred Rogers than Fred Rogers.” It’s one of the ones that jumps off the page, amongst others, reading the book. The foreword alone is reason for our listeners to rush out and take it up.

Before we get to the lasting implications of Mister Rogers and his model, why don’t you just talk a bit about what he meant to the two of you and others from your generation?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Well, I should say, Sean, that we are of separate generations.

SEAN SPEER: [laughs] Pardon me.

GREGG BEHR: Yeah, that’s fair.

SEAN SPEER: Do you want to start Gregg?

GREGG BEHR: Yeah, I go back to what I mentioned previously. I’m a child of the ’70s, and I was an avid and active viewer, along with my brother and particularly my mom, of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. And I still remember, Sean, the first time that I met Mister Rogers. I met him as an adult. That giddy seven-year-old self that I experienced at that moment. If I have two heroes in this life, one of them is Fred Rogers. My other one is Roberto Clemente, the famous Pittsburgh Pirate baseball player. And both of them, for me, lived out this idea of making goodness attractive. And I’m not someone who believes one needs heroes in this life, but you need markers, and Fred Rogers is a marker in my life.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Yeah, I would say for me, he was—I don’t have specific memories of being a kid and watching Fred. I think that’s because he was just on all the time; he was this constant presence. The fact that Gregg mentioned earlier, the way he put so much science into the program, every scene you could pick out, once you understand the science behind it, you see it everywhere. And the fact that he put that much intention into everything he did for more than 900 episodes over the course of almost more than 30 years, and that he was in my house every day doing something that was grounded in science because he knew that was best for me, I don’t think I quite understood that at the time.

But going back to the Neighborhood as an adult, when Gregg and I set out on this project and rewatching episodes, and suddenly I’d see a scene and be like, “Oh, I remember that.” I’m in awe of Fred, the amount of work he was able to sustain over such a long period of time, and the genuine wanting the best for his viewers over such a long period of time. He rejected sponsorships that could have made him fabulously wealthy because he wanted to give kids the best possible television program. The fact that he did that for so long, for so many kids I think he deserves all the accolades that he continues to get.

SEAN SPEER: Yeah, I would just make two quick observations before we pivot to the potential for a new generation to engage the ideas and model of Fred Rogers. The first is, one idea that really is prominent throughout the book is the sense of responsibility that, as you say, Ryan, he felt like he had to his audience. This is not someone who was flip at all, ever, about the work that he was doing. The second, I would just say, the extent to which we have, from my era anyway in Canada, something of a comparable model it would probably be Ernie Coombs, who was famously Mr. Dressup. I’m afraid I don’t know if he was inspired by the same understanding of the science behind child development, but he similarly, I think, sought to produce child programming that reflected that same sense of goodness that you both have been talking about so far.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Yeah. It’s amazing when you watch those two programs side by side, they’re remarkably similar. And in fact, Ernie Coombs started his career here in Pittsburgh as an understudy for Fred Rogers. When Fred was called up to Toronto and offered the 15-minute Misterogers spot, Ernie went with him. And when Fred decided to come back to Pittsburgh, he said, “Ernie, you should stay. You have an opportunity here.” And that opportunity, of course, became Mr. Dressup. The two have been compared often: Ernie’s called the Canadian Mister Rogers, or Fred is called the American Ernie Coombs. They knew each other well, they studied together, and the influence they had on one another is quite apparent.

SEAN SPEER: Yeah, that’s wonderful. We’ve spoken a lot, Gregg and Ryan, about Mister Rogers’ educational philosophy and the key principles that underpinned his work. What would you say to those who might argue that his approach is no longer applicable in today’s age of the internet and short attention spans and the kind of zero-sum competition that parents face to get their kids into good schools and get good jobs, and all the rest? Make the case for the ongoing relevance of Mister Rogers and the ideas and values that underpinned his work.

GREGG BEHR: In our world, Fred Rogers’ name is etched into the sides of walls and schools of education across this continent, around the world. There is Vygotsky, Montessori, and Fred Rogers. He was an extraordinary educator who understood and appreciated the atmospheres for learning, as he used that phrase. The atmospheres for learning, that we need to create for young people so that young people feel safe, that they feel loved, that they feel accepted, that it’s okay to ask great, big questions. He understood the incredible grounding that every child needs with the support of caring adults in their lives, before they then pursue academic or extracurricular, or whatever pursuits it might be that drive some sense of excellence for that person, or, I suppose, for that person’s parents, or whatever it might be. He understood the atmosphere that we need to create for kids so that they could be their authentic selves and also be best positioned to succeed on their own terms.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: I would add that I think something that gets lost when we talk about Fred as adults is we tend to look back at him with a bit of nostalgia, we look back on him as maybe a little quaint, maybe a little dated. I certainly did before we began this project. But then you go back and you realize that the tools for learning that Fred was cultivating in the Neighborhood, things like curiosity, and creativity, and collaboration. When you look at the cutting-edge science coming out of our top universities around the world today, again, what Gregg mentioned earlier, what we’re learning about learning itself, they’re saying what’s most important is exactly what Fred was cultivating 50 years ago. These tools they cost almost nothing to develop. They hinge on the very things that I think make life worth living: self-acceptance and close and loving relationships, and a deep regard for our neighbours. I think most wildly to me is that they’ve been shown to be up to 10 times more predictive of children’s long-term success than test scores. Fred Rogers is absolutely relevant, not just because he was a nice guy, not just because he reminds us of our childhood, but he demonstrably, measurably, tangibly can still continue to have an impact on children growing up today.

SEAN SPEER: Why do you think there’s been something of a Fred Rogers resurgence in recent years? What does it tell us about how people feel about him? But, perhaps more importantly, how they feel about our current cultural landscape and the messages and ideas that our children are being socialized in?

GREGG BEHR: There are many answers to this question. Previously, Ryan mentioned the word generations. Generations of Americans, and even, to some extent, Canadians, grew up with Mister Rogers. And so there’s an emotional catch to that, and add to that context, then, that Fred Rogers Productions is now once again the largest producer of children’s television for PBS, the public broadcasting system here in America. Such that you have programs like Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, the modern animated successor to Fred Rogers. So you have a generational connection, and I think that inevitably raises up Fred and his impact. It’s also true Ryan mentioned the cultural impact. You had Tom Hank’s biopic, you had Morgan Neville’s amazing documentary. So you’ve had some very popular and commercially successful pieces that have brought Fred Rogers back to the cultural fore.

And then I do think, sadly, especially given the violence in this country and how often, in those moments, people will turn to something that Fred once said, and that is, in these moments of despair to look for the helpers. And the second part of that is look for the helpers, because then you’ll know there’s hope. And even just that phrasing and bringing forward the wisdom of Fred in those tragic moments has brought Fred back to the fore. So I think it’s a bit complicated as to why Fred is so much part of our current landscape, and he deserves to be.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: Yeah. And I would just add that Fred used to say that we all need to know that we’re worth being proud of, right? Whether we’re a preschooler or a young teen, or we’re a retired person, we all need to know that our existence makes a difference in somebody else’s life, right? And I do think that we don’t get that message too often that we’re worth being proud of. In fact, there are all sorts of tools and applications and programming out there that tells us the opposite. I don’t know that many people scroll through Instagram and think, “Oh, I’m worth being proud of.” I think they have the opposite effect, “I need to be more X, Y, Z. I need to make more money. I need to be more attractive.” There is something timeless and I think increasingly urgent about our need to feel that we’re worth being proud of. And Fred continues to offer that.

SEAN SPEER: Yeah, that’s right. It’s just such a powerful vision of a radical sense of dignity that, as you say, Ryan, is needed now as much as ever.

Let me ask a penultimate question. I alluded to it earlier. I have young children, and I’m struck by how competitive parenting seems to be. Let me ask a two-part question. First, is this, in your view, a new phenomenon? And second, how does it contrast with Fred Rogers’ conception of parenting and child development?

GREGG BEHR: Well, here, you’ve stumped us because we would never profess to be perfect parents. In fact, one of the hardest things I think about writing and publishing this book is that, in some senses, we’re now looked to by some as experts in education and parenting, and we’re far from perfect people. I do find personally that I am challenged all the time by Fred’s lessons. And sometimes it’s in the very small moments. My kids, who are a bit older than yours, asking a thousand questions and just being frustrated and not having the answer, and I just want to say, “Stop,” right? But just being mindful of these sorts of simple things Fred might have said to invite those questions and let them know that it’s okay to have those questions, and we’ll wonder about them together.

I’ll share a very personal story. This was a couple of years ago. There’d been a terrible mass shooting in Atlanta of Asian Americans. I mention that because my wife is an Asian-American, so my kids are of mixed race. And out of the blue, in a very quiet moment, sitting in our living room, my daughter turned to me and said, “Daddy, am I going to be shot?” Well, apart from being frozen, in that moment, I realized the news of the day had gotten into our living room, despite my best efforts to protect her from the sometimes craziness of this world that can be beautiful and it can be awful, right? And Sean, it was like the lessons of Fred came rushing home to me at that moment. I need to let her know that she’s going to be okay, that she has caring, loving parents, adults right around here, that it’s okay to have these big questions and these big feelings, and that it was okay for me not to have the answers and to let her know that, but to let her know that we’re going to think about those things together.

We are challenged, I think, in every day in ways big and small about Fred Rogers’ philosophy. I think for the parents and the teachers, and others across this continent who’s read this book, it’s been both a reminder of the atmosphere that he created for us and the things that we can do—the doable, spreadable, actionable things that we can do to be a little more Fred-like in our own work.

SEAN SPEER: Based on our conversation so far, which has just been so insightful and also encouraging, what can a rediscovery of Fred Rogers’ philosophy do for a new generation of kids?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: I can tell you what it’s going to do for the new generation of kids in my house. My son is nine months old. And you mentioned parenting, feeling competitive, and I’ve absolutely seen that already. We live in a neighbourhood with tons of young families, and we’re confronting all of these questions that I never had to think about before. Like, where’s he going to go to school? What kind of toys does he need? Is this developmentally appropriate? And all that stuff. I don’t want to minimize that stuff because those are important questions and things that all families have to grapple with. But I will say what has been most helpful for me, what’s been most clarifying for me, has been that sense that if I can just show my son, if I can just let him know every single day that there is someone who loves him just the way he is, even on his worst days, and letting him know that there is nothing he could do that could ever change that, that’s the most important thing. That is the thing that supersedes all else. Without it, the schools don’t matter. The toys don’t matter; nothing matters.

And I think getting back to that sort of foundational philosophy that Fred expressed for so long and that he expressed so well, that’s become my North Star. And like Gregg mentioned, we’re far from perfect. It’s not always easy, right? But if I can do that one thing, then I feel like I’m moving in a direction in which I am more like Fred. And his message to parents, his message to adults, was never try to copy me; try to be the next Mister Rogers. It was always be more yourself. So the work for me, the work for parents is trying to figure out how, in my own way, am I going to show kids, how am I going to show a new generation, that they are liked, that they are worth being proud of just the way they are?

GREGG BEHR: So much of this rediscovery is about the grownups; it’s about the things that we do. And it’s why in our book we try and give very concrete examples in schools, in museums, and libraries in ways that, in 2023 and beyond, the caring adults in kids’ lives are creating these atmospheres for learning that cultivate and promote curiosity and creativity and working together in communications and connection in ways that are powerfully important for the learning experiences in these young kids’ lives. And it’s the systemic approach that we grownups can take again, in our school systems and other sites of learning, that could have the most powerful impact if we genuinely study what it was that Fred did.

SEAN SPEER: I said this would be the final question. One of my favourite introductions to a book is the biography of Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, by the well-known British historian, A. J. P. Taylor, who was friends with Beaverbrook. He wrote in the book’s introduction that he had promised himself that if he discovered something about Aitken over the course of the project that caused him to see his friend differently in a negative way, he would simply cease the project. And instead, the more he worked on it, he said, “I learned that I loved him even more than I realized.” What did you guys learn about Fred Rogers that you didn’t know before you started this project?

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: I could tell you mine that something that jumps to mind because it was probably the most profound experience that I had when we were putting this book together, and I was in the Fred Rogers Archive in Latrobe, which I mentioned earlier is Fred’s hometown. It’s a small town, just about 40 miles to the east of Pittsburgh. There’s a little college there called St. Vincent College. And this house is the Fred Rogers Archive, which is a totally unremarkable room. It’s an office like this with fluorescent lighting and a bunch of boxes. So if you walked in, you wouldn’t even know where you were. But in those boxes are decades worth of correspondence to Fred—every letter he ever received. And Fred received a lot, sometimes upwards of 50 to 100 letters a day, and he responded to all of them.

So if any of your listeners have ever written a letter to Fred, they can probably go find it in this archive. So we spent hours just going through these letters and reading them. And what people shared with Fred was so vulnerable, especially what children would share, “Mister Rogers, I’m sick,” or “Mister Rogers, my dog died,” or “Mister Rogers, my parents are getting divorced.” What was so remarkable to me was the fact that you can look at Fred’s notations in the margins and you see him thinking about how he’s going to respond. And in many ways, you could draw a direct line from those letters to the things he then would turn around and talk about on Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. I really came to see this television program, which of course is a one-way medium, began to see the Neighborhood as a conversation. Fred was always listening; he was always in conversation with his viewers. And that, to me, was so profound in a new way of thinking about him as a television host.

GREGG BEHR: And it speaks to Fred’s kindness. I mean, even still today, it’s hard not to think of him in a saint-like way. And Joanne Rogers, whom we had the pleasure of knowing, and I knew the last decades of her life, she was really careful to say to us like, “Don’t present Fred as a saint.” Like the guy could get mad, he could get angry. He had troubles like the rest of us did. Fred Rogers was no saint, but what he did do was he was deliberate and intentional. Whether it was about practicing kindness or about thinking through the words, the puppetry, the songs that he put together on each television program, he was deliberate and intentional. And that’s the thing that blew me away in the course of this work.

SEAN SPEER: Well, guys, this has just been a wonderful conversation about a wonderful figure and a wonderful book. It’s entitled, When You Wonder, You’re Learning: Mister Rogers’ Enduring Lessons for Raising Creative, Curious, Caring Kids. Gregg Behr and Ryan Rydzewski, thank you so much for joining us at Hub Dialogues.

GREGG BEHR: Sean, thank you for having us.

RYAN RYDZEWSKI: It’s been a pleasure. Thank you.