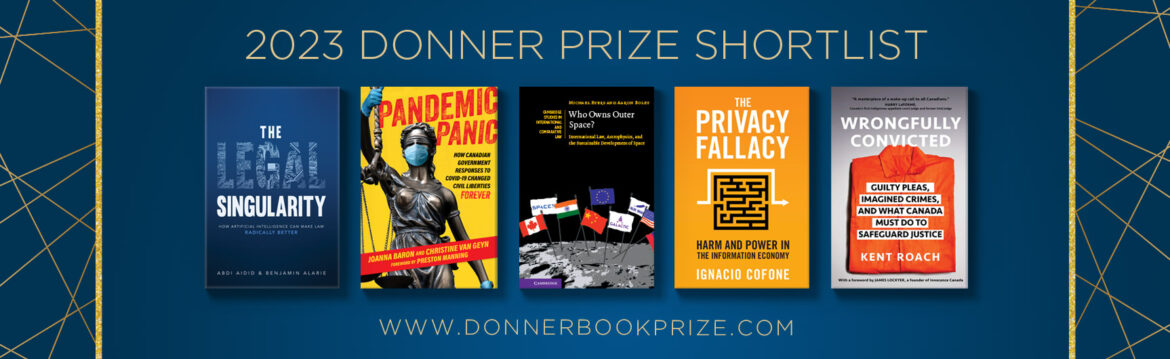

As part of a paid partnership, this month The Hub will feature excerpts from this year’s five shortlisted books for the Donner Prize, awarded to the best public policy book in Canada. Our podcast Hub Dialogues will also feature interviews with the authors. The winning title will be awarded $60,000 by The Donner Canadian Foundation on May 8th.

The following is an excerpt from The Privacy Fallacy: Harm and Power in the Information Economy (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

All your interactions, movements, and decisions are collected in real-time and attached to profiles used by advertisers to compete for your attention. Not because they think you’re special or because they’re interested in learning about you for the sake of getting to know you, but because, regardless of your age, gender, or country of origin, you’re monetizable. When combined, these little pieces of ourselves fuel a trillion-dollar industry that threatens livelihoods, lives, and democratic institutions.

The worst part is not that we get little in exchange. It’s that, much like companies that pollute the atmosphere or that offshore production to places where they can violate workers’ human rights, every step of the data industry creates losses and harms that are opaque but real. Companies that collect, process, and sell our personal information create harms that are out of sight but have dire consequences for those affected.

Clara Sorrenti experienced firsthand the consequences of data harms. She received death threats, had her home address found and shared, saw intimate documents about her family revealed, and was “swatted”—the practice of falsely reporting a police emergency to send armed units to an innocent person’s home, an experience that, for Clara, ended up with an assault rifle pointed at her head. Clara was a victim of Kiwi Farms, a platform that coordinates the gathering of information available online to target trans people. For the law to consider that you harassed someone, you need to contact them several times. So, if a platform pools information and coordinates people who each contact a victim once, as was the case for Clara, it produces harassment while avoiding its legal definition.

Describing her experience, Clara explained: “When you get your own thread on Kiwi Farms it means there are enough people who are interested in engaging in a long-term harassment campaign against you.” She left her home after the swatting incident, but Kiwi Farms found her by comparing hotel bedsheet patterns from a picture she took with information available online. Clara fled the country to escape abuse and Kiwi Farms found her again.

Viewing Clara’s harassment as the work of a few bad individuals ignores a broader systemic problem. In our digital ecosystem, it’s easy to obtain and use our data in ways that inflict harm on us —like a roommate exploiting a teenager’s sexuality for entertainment or a website exploiting trans women’s physical safety for dollars. Because Clara’s harms weren’t just a result of individual trolls, but rather emblematic of an ecosystem that enables and magnifies data harms, her situation is not exceptional. Part of what’s shocking about her stories is that she faced enormous harm from something as common as webcams and blogs.

Data harms differ. Some are visible and affect people such as Clara on an individualized basis, with immediate consequences on their livelihood. Daily victims include women facing online harassment and abuse, racialized individuals experiencing magnified systemic discrimination, and anyone going through identity theft because their financial information was taken without their knowledge. Most harms in the information economy, however, are opaque and widely dispersed. Examples are online manipulation to make personal and financial choices against our best interests (called “dark patterns”) and the normalization of surveillance to constantly extract personal data (called “data mining”).

Clara and other victims are pulled into the information economy—the trillion-dollar industry fueled by the collection, processing, and sharing of personal information to produce digital products and services. When we look at data interactions, we sometimes forget that it’s there. For example, in the nonconsensual distribution of intimate images, there’s a tendency to concentrate all blame on the first perpetrator. But when intimate photos go viral, that means hundreds of people reposted them and websites derived ad or subscription profit from them. Victims are harmed because there’s a data ecosystem that facilitates and encourages it.

The information economy enables corporations and individuals to instrumentalize others for their own gain—and it amplifies them. So cases of one perpetrator and one victim barely exist. We lack accountability over what happens with our data and what harms happen to us because of our data. By having a better picture of that data ecosystem, laws can better reduce and repair data harms.