One of the most interesting features of the COVID-19 pandemic is the wide gulf across different countries in death and positivity rates.

Some of the most heavily affected countries to date in terms of total cases include the United States, India, Brazil, France and Russia. Next come Turkey, the United Kingdom, Italy, Spain and Germany. On the other hand, countries like Taiwan and New Zealand have done very well.

There are of course unique features about the progression of COVID-19 in each of these countries based on timing of the initial infections as well as the effectiveness of response mobilization, particularly in the early stages. One might be tempted to conclude there is no real pattern here other than some really bad luck.

However, what at first may seem like a diverse collection of the more heavily affected countries in terms of characteristics such as level of economic development, urbanization, geographic size and population density obscures the fact that many of these heavily affected countries have a common feature. Half of them — the United States, Brazil, India, Russia and Germany — are federations. Of the remaining five, three of them have high degrees of regional political devolution or decentralization, namely the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy.

This raises the question: has political decentralization been bad for COVID-19 response and management?

Fiscal and political decentralization has long been advanced as an important policy goal as it allows for tailoring of programs and policies to grassroots populations, accommodates regional and cultural diversity, allows for innovation in public policy through jurisdictional experimentation and may even restrain tax growth and public sector size via competitive governments.

Decentralization has achieved its highest expression in federalism, which is an economic and political institutional organization designed to combine the advantages of a central state and unified economic space with those of autonomy and regional preferences.

For some, federalism may be the optimal form of government especially in countries marked by large degrees of cultural, geographic or regional diversity. And federations like Canada, the United States and Australia have been among some of the most successful countries in the world in terms of standards of living, public freedom and political stability. And yet, any federation has inherent tensions between the centre and the periphery, between lower and upper tier authorities. Canada has been no exception with its perennial tug of war between Ottawa and the provinces.

Remember the old joke about federalism that goes something like this? The United Nations asks for a report on elephants from all of the member countries. The United States submits: “How to Raise Elephants for Fun and Profit,” the United Kingdom responds with: “Should We Invite an Elephant to Tea,” while France chimes in with: “The Love Life of the Elephant.” And Canada? It appoints a Royal Commission to draft the report and comes up with “The Elephant: A Federal or Provincial Responsibility.” That is funny, well, at least to some people.

On the other hand, during a pandemic, “Vaccines: A Federal or Provincial Responsibility?” is not so funny to anyone given the current spread of COVID-19 variants and the race to vaccinate.

Have federations been dysfunctional in their pandemic response?

Good question and one that needs to keep as many things constant in the mix as possible. For starters, let us just stick to the thirty-five advanced economies as defined by the International Monetary Fund. Of these, seven are officially federations, that is they have governments that are an amalgam of two or more tiers that are both separate and coordinate each with some degree of political and economic power. These are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Switzerland and the United States. However, to this list we should also add countries which, while not officially federal, have over time devolved more powers to regional authorities: Spain, Italy and the United Kingdom.

Spain is not a federation but a unitary state with substantial decentralization as well as autonomous regions. Italy is also a unitary state but again with substantial devolution over the last 50 years. For example, while there is a national health service in Italy, the delivery is by regional authorities and health care service quality can differ across the regions. Then there is the United Kingdom, which is not a federal system, but there has nevertheless been political devolution to Scottish, Welsh and Northern Ireland assemblies and as a result different and asymmetrical relationships with London which also affects spending and taxation.

In other words, the dividing line may not be federal versus non-federal but more decentralized versus less decentralized countries.

So, if we obtain some pandemic statistics for the first twelve months of the pandemic for these thirty-five economically advanced countries and compare between more decentralized and less decentralized countries, what do we get?

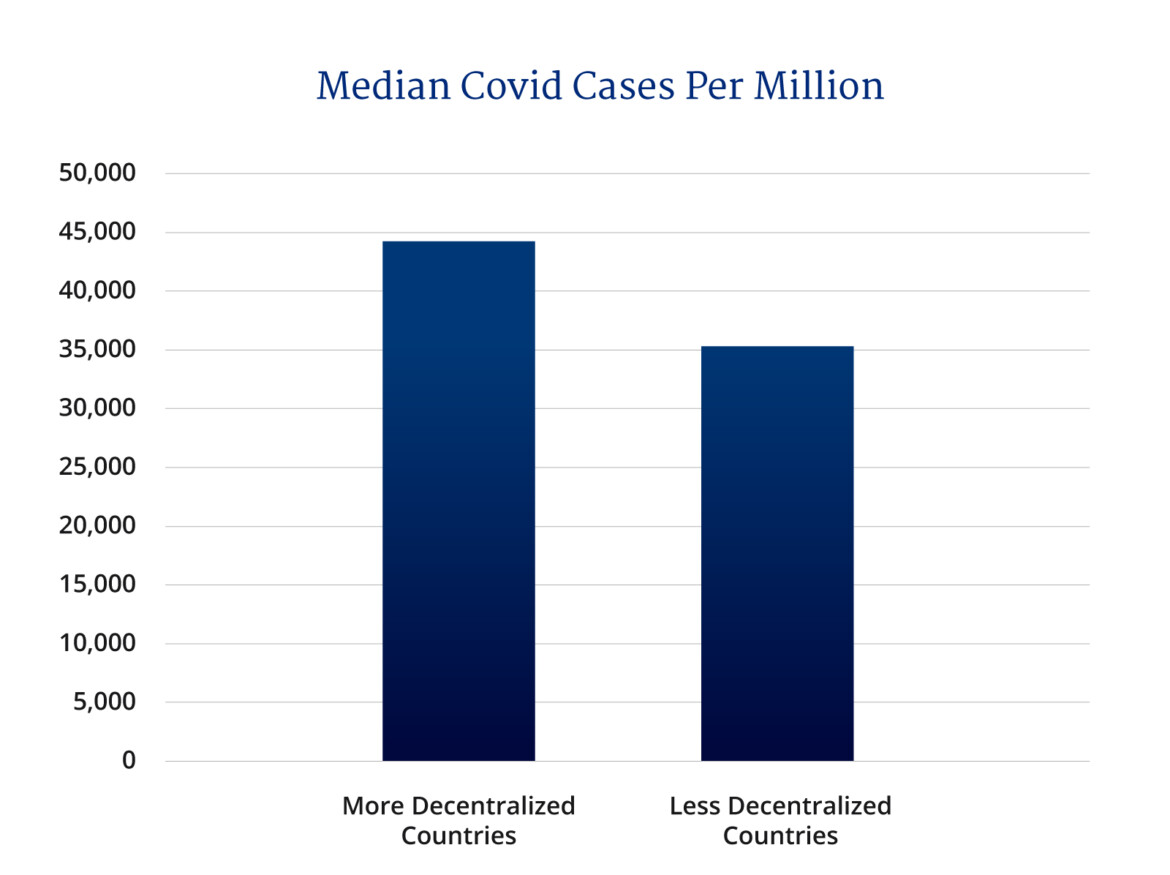

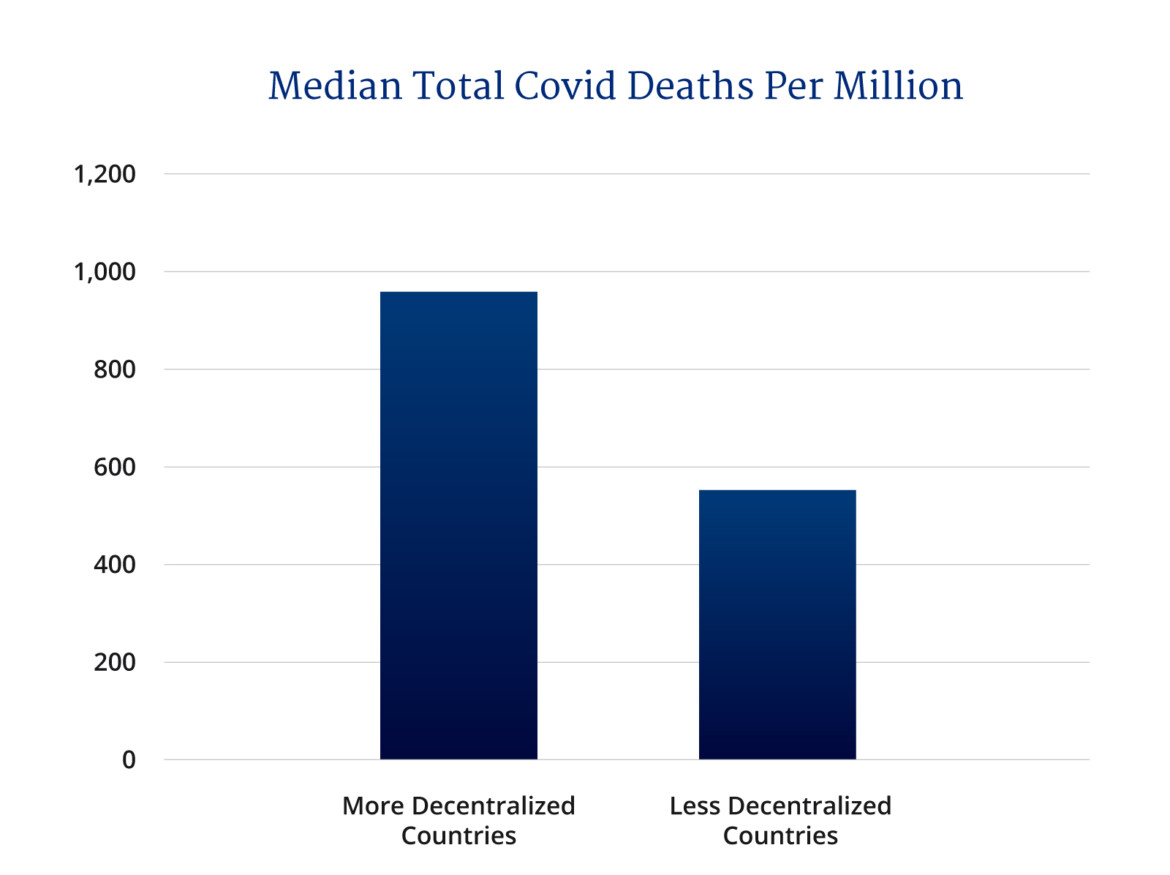

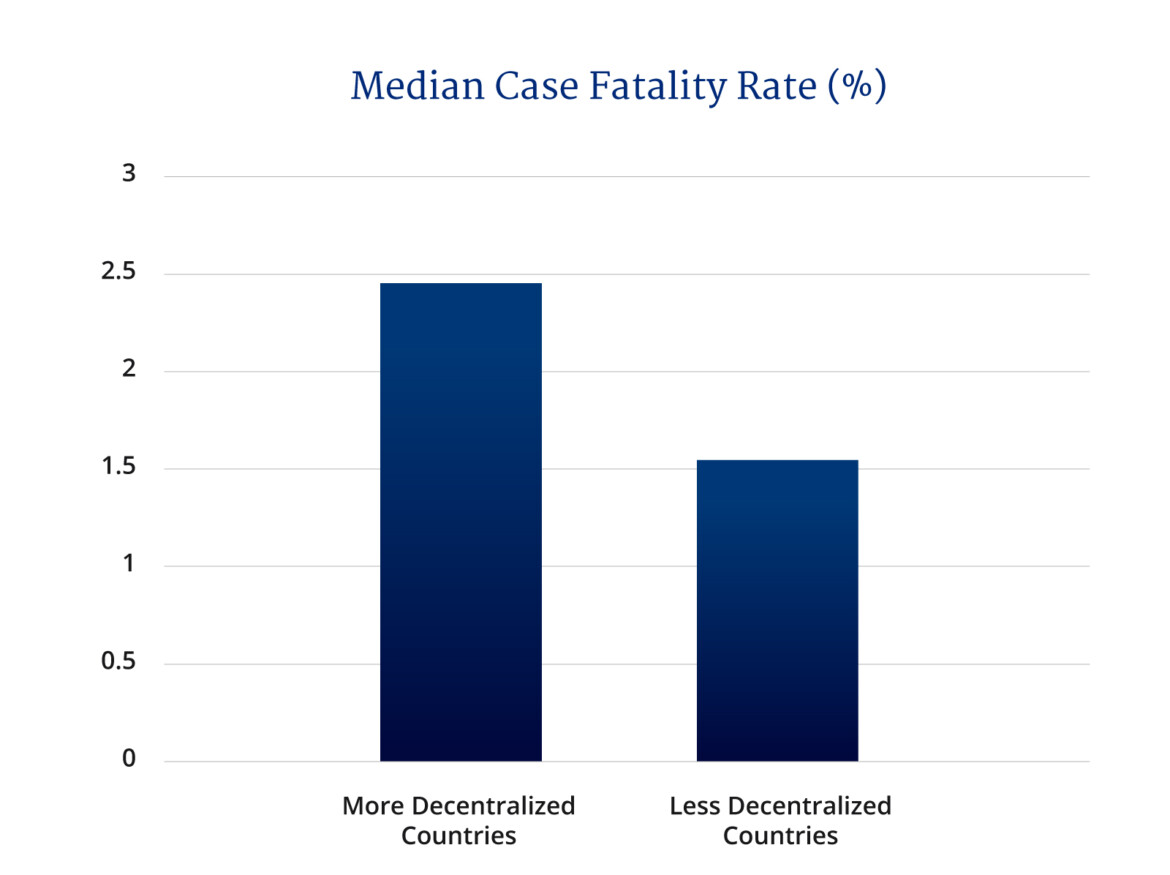

Well, when you look at median COVID-19 cases per million, the more decentralized countries had 25 percent more cases per million than less decentralized countries. As for median COVID-19 deaths per million, these ten more decentralized countries clocked in at 74 percent more, whereas the case fatality rate was 59 percent more. How about responses and dealing with the pandemic? These ten more decentralized countries conducted 16 percent fewer median COVID-19 tests per million population and the median stringency response as measured by the Oxford Stringency Index was 5 percent lower. Not a big difference but still a difference.

Of course, there are all kinds of unique factors for each of these countries when it comes to dealing with the pandemic that, taken together, might contribute to the difference. Italy and Spain for example have some of the oldest age distributions in the IMF advanced economies.

Meanwhile, the United States entered the pandemic with a particularly dysfunctional commander in chief. As for Canada, it did particularly poorly on protecting its elderly in long-term care facilities. Australia, on the other hand seems to have done rather well but it is an island continent and history shows they did relatively well during the Spanish Flu 100 years ago also.

Still, as the analysis and research on the pandemic unfolds in the years to come, a lingering question will remain: how much of the relatively poorer response of decentralized countries with overlapping jurisdictions during the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to the difficulties in coordination of response across governmental tiers during times of crisis?

More importantly, assuming there is anything to be learned here, what can they do to improve crisis performance the next time around?

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Peter Menzies: The mainstream media should love Doug Ford, now that he’s subsidizing them

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by