The mandate of the Bank of Canada is to keep inflation in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) within a range of one percent to three percent, with a two percent target (IT). It is frequently overlooked that the Bank of Canada Act also states that the Bank must “…promote the economic and financial welfare of Canada.”

The current policy regime, if renewed, will begin its fourth decade. As former Governor Gordon Thiessen argued almost 25 years ago, other strategies may also deliver good macroeconomic outcomes, but “….the benefits of the clear operating framework provided by such targets will make them increasingly attractive in democratic societies that demand accountable public institutions.” Accountability is the cornerstone of good governance because monetary policy is managed by appointed, not elected, officials.

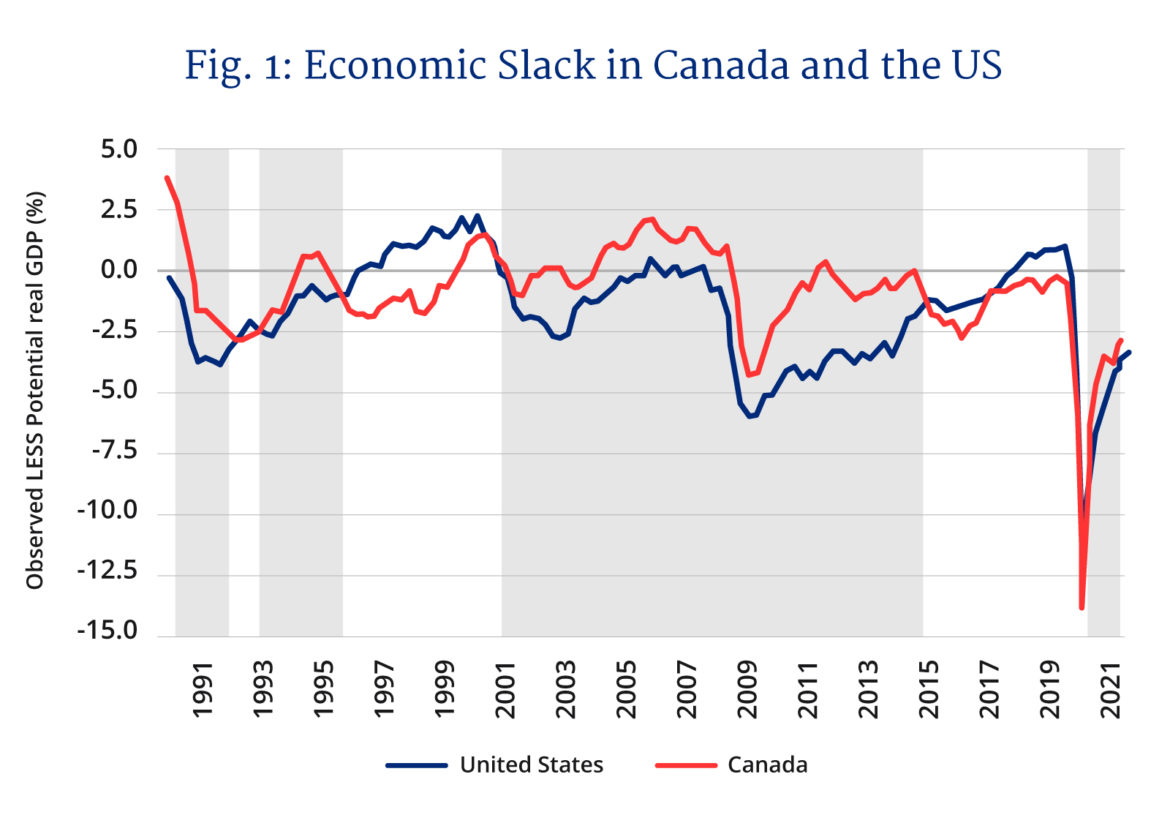

Central banks often evaluate inflationary pressures by estimating the amount of slack in the economy. When slack is low, the Bank can ease monetary conditions, and vice-versa when production exceeds the economy’s potential. The Bank’s estimate of slack or output gap is shown below, alongside U.S. data. While the U.S. Federal Reserve adopted an IT of two percent, it serves only as a guide since the Federal Reserve has a dual mandate of maintaining stable prices and economic activity around potential.

While U.S. and Canadian macroeconomic performance has been comparable, slack is often smaller (and less volatile) in Canada. Therefore, the output is closer to potential in Canada (U.S. average real growth is 2.29 percent versus 2.12 percent for Canada between 1992-2021). Unfortunately, whereas inflation is observable, slack is unobserved and must be constructed. Unsurprisingly there is considerable debate about how much slack exists at any given time.

Accountability implies transparency. Critics of the current policy regime need to ask whether alternative strategies can improve economic prospects clouded by a pandemic. The simple answer is no. Historically, neither exchange rate pegging nor the targeting of monetary aggregates meets the standards of transparency. The former because it disguises broader economic imbalances that usually lead to a collapse of the regime; the latter because it is subject to the whims of money supply definitions. Nominal GDP targeting is also sometimes mentioned as a solution. However, it gives considerable latitude to policymakers, when aiming for a stated target, to change the weight they will place on inflation versus real GDP growth. The dual mandate presumes that the Bank is unconcerned about real economic performance. Yet, Canada’s legislation asks the Bank to concern itself with the country’s overall economic welfare.

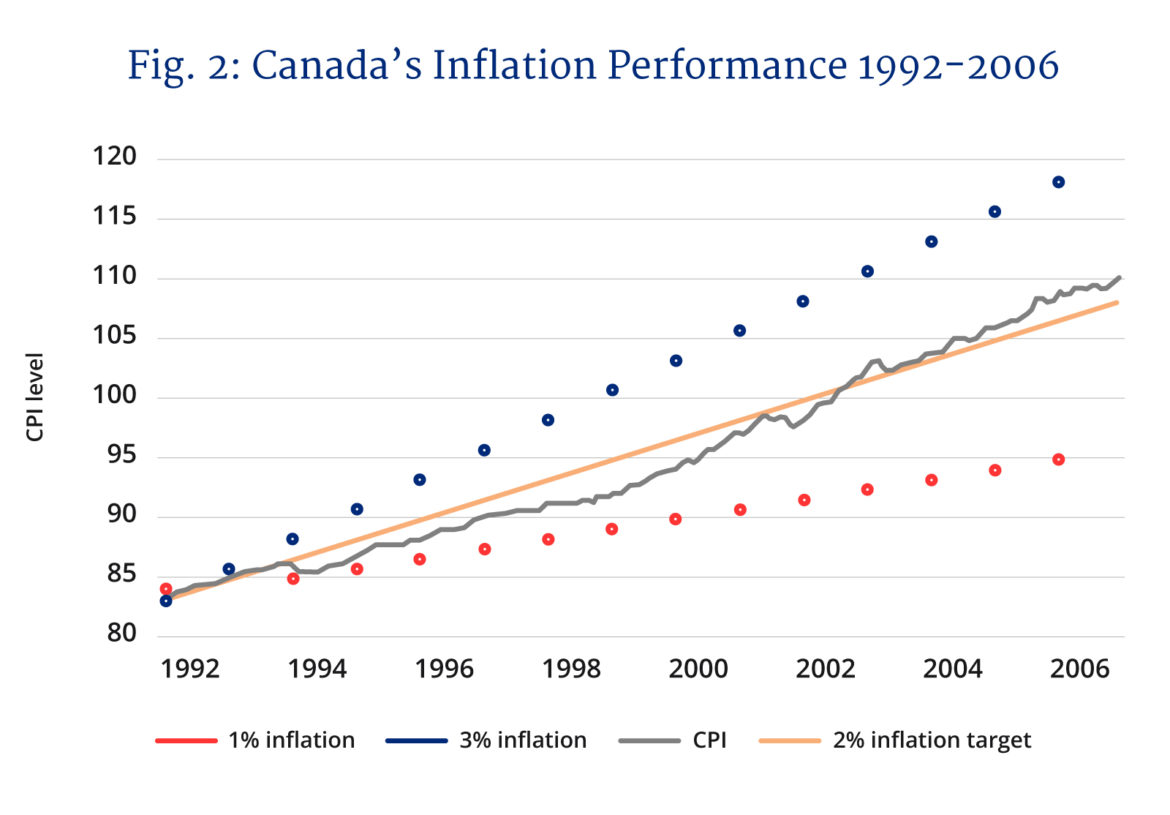

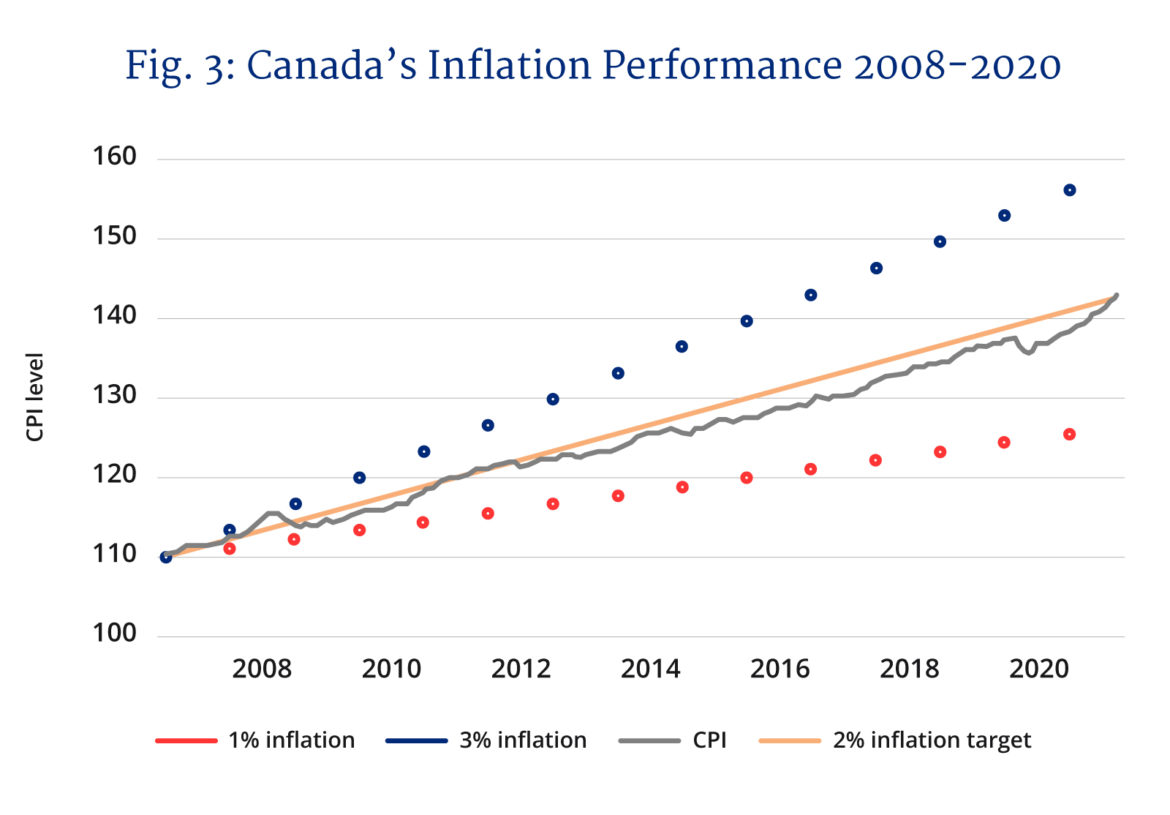

Assuming that some version of inflation targeting defines the Bank’s mandate beyond 2021, can any improvements can be made to the existing framework? It is worth briefly looking at history. The graphs below divide history into roughly two 15-years long halves. The first period begins shortly after targets were introduced until shortly before the Great Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. The second period begins thereafter until the present. Straight lines show what happens to CPI if annual inflation is exactly one percent, two percent, or three percent starting from the beginning of each period. The black line shows how actual CPI evolved over time. Actual inflation drifts around the two percent target for as long as we’ve had an IT. There have been no real threats to breach the upper or lower edges of the target range. Nevertheless, the CPI has tended to drift away from the two percent objective for considerable periods of time. While the first period overlaps with what former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke called the Great Moderation, the era since the end of 2007 has been anything but placid. The Great Financial Crisis, the Eurozone debt crisis, and the ongoing pandemic have dominated economic events since 2007.

How much credit should the Bank get? There are those who have argued that luck helped many central banks until 2007 thanks to small surprises (called shocks by economists). The rise of China as a global economic power may also have helped moderate price increases.

Something else happened after the Great Moderation ended. The policy rate, an interest rate used by the Bank to keep inflation under control, was on average 4.35 percent until the end of 2006. Since that time the average policy rate has stood at 1.24 percent. This is a substantial decline that shows no signs of being reversed any time soon.

Next, central banks in Japan, the U.S., Europe, and the UK purchased financial assets of various kinds and generally eased credit conditions. The collection of these policies is termed quantitative easing (QE). The Bank also joined the QE club when the pandemic erupted since there was little scope to ease monetary conditions via interest rate cuts. Measures were taken, such as the purchase of long-term government bonds, provincial bonds, and even corporate bonds. As a consequence, the Bank’s balance sheet swelled 11-fold between the end of 2006 and its peak, reached in February 2021. To its credit, the Bank ended QE in October 2021as pandemic conditions ease. While the balance sheet will shrink over time it is also likely to remain at historically elevated levels for the foreseeable future. Nevertheless, this episode, along with other ongoing economic and societal forces, has potential repercussions for the Bank’s mandate going forward.

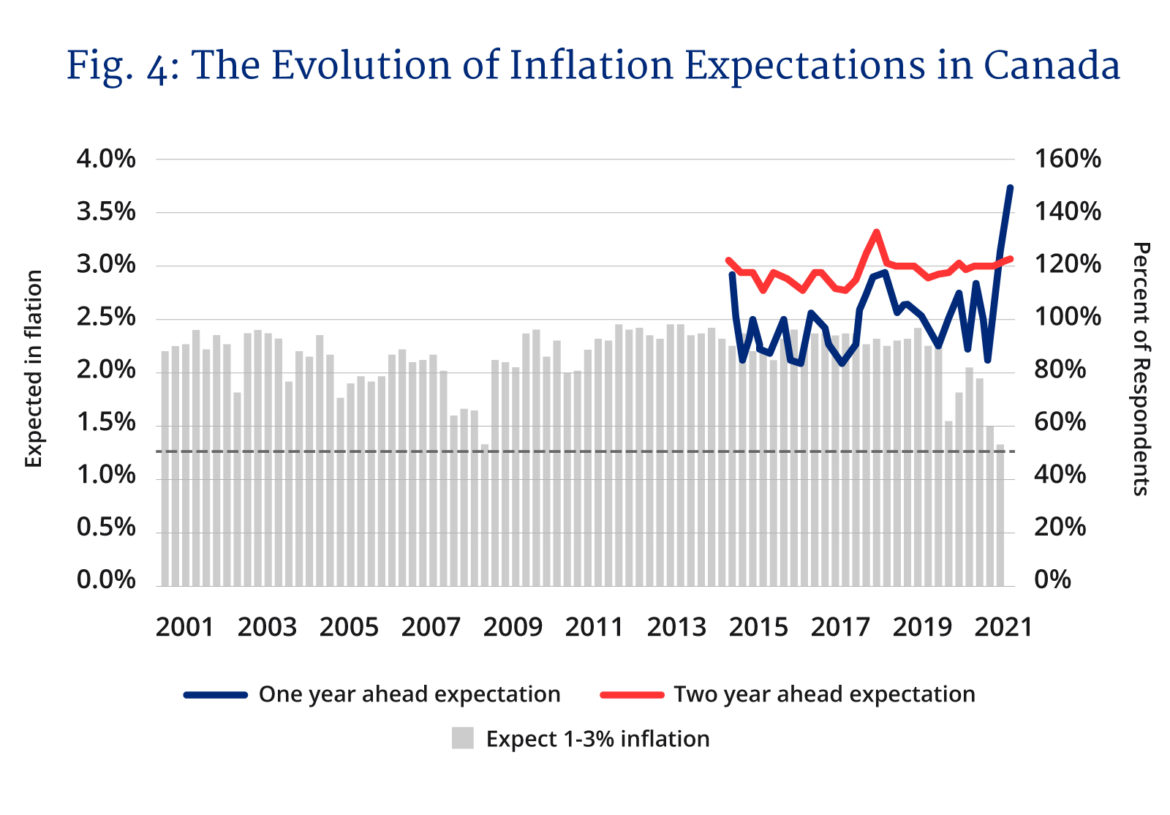

Returning to the Bank’s performance, another measure of its impact is reflected in how well it steers the public’s expectations about future inflation. After all, if the central bank is committed to two percent inflation, then the public should have confidence that it will deliver it in the future.

Other than in 2009 and again following the pandemic, the majority of businesses believe inflation will remain in the one to three percent target range. However, notice that it does not take long for bad news about inflation to reverse businesses’ faith in the target. The public, on the other hand, is less confident, with inflation expectations over the next two years close to the top end of the target range. Notice the volatility of one year ahead expectations, which may indicate that consumers are quite sensitive to recent news about inflation. Ideally, central banks aim to anchor expectations at two percent. The burning issue now is whether the recent rise in inflation is transitory or more permanent. If the anchor is lost then the upper range of the IT will be threatened, as will the Bank’s credibility. Faith in the maintenance of the target is fragile and any mandate must seek to strengthen the public’s view about the Bank’s ability to achieve its target.

Where do we go from here? The old adage: “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” applies. However, the Bank faces greater threats. Even before the pandemic, climate change, inequality, and lacklustre economic growth, to name just three issues, were challenges faced by public officials. The arrival of digital currencies may tempt some governments to ask central banks to issue the proverbial “helicopter money”. QE, largely essential over the past 18 months, will return if the economy continues to disappoint. Japan has relied on QE-style policies for over two decades while the U.S. has followed the same strategy for well over a decade. While there is a case to be made that, absent QE, economic performance would have been worse, QE did not reverse the low inflation-low growth combination. Clearly, monetary policy is not enough.

It has always been true that monetary and fiscal policy must function in concert. A reminder is needed that the central bank is an institution within government and not outside of it. The greater risk is that central banks will be asked to do too much, not whether or not a new form of IT is adopted. A cynic would argue that this suits politicians because the blame for poor outcomes can be shifted elsewhere. A more charitable view is that to promote the welfare of Canadians, monetary and fiscal authorities must work together. It is the checks and balances provided by the institutions jointly responsible for monetary policy and financial stability that provide the best guarantee of accountability. The Bank’s focus on inflation is the best guarantee against a mandate that tries to be all things to all people. However, once the target is renewed, the contract between the central bank and the government will need to be improved.

Recommended for You

Falice Chin: A tale of two (Poilievre) ridings

Evan Menzies: Calgary at 150: Why is it so hard to celebrate our history?

‘We’re winning the battle of ideas’: Conservative MP Aaron Gunn on young men moving right, the fall of ‘wokeness,’ and the unraveling of Canadian identity

Laura David: Red pill, blue pill: Google has made its opening salvo in the AI-news war. What’s Canadian media’s next move?