I am the CEO of the MEI, formerly known as the Montreal Economic Institute. The MEI is a public policy think-tank whose work is based on research and data and its interpretation. However, I increasingly feel that if we aspire to spread better understanding of the institutions conducive to a free and prosperous society, we must also explore and explain the philosophical foundations of these ideas. I feel that often we make it too easy for our detractors to paint us as “efficiency zombies” who would willingly sacrifice their own mothers on the altar of the market if it produced even marginal GDP growth. If we want to sell people on our ideas, we must also sell them on classical liberalism as a philosophical tradition that rests on genuinely valuable ethical foundations.

There are two common attacks that get thrown at classical liberals by both the left and the right that supposedly prove the bankruptcy of classical liberalism.

The first is that classical liberalism is essentially nothing more than an endorsement of selfishness and libertinism, and encourages a society in which people can behave without restraint or responsibility. The left accuses classical liberals of endorsing a selfish egoism, while the right accuses classical liberals of a self-centred hedonism.

The second and more subtle form of attack is that classical liberals are themselves the moralists without realizing it. These attacks, both from dyed-in-the-wool Marxists on the left and reactionaries on the right, suggest that classical liberals elevate liberty to the status of the highest good — that we make freedom an end in itself and render it the summum bonum, the highest moral value that we should prioritize.

These attacks misunderstand what classical liberalism, with its concern for liberty, is ultimately about.

We don’t value liberty purely as an end in itself and we don’t simply value liberty because we are nothing but libertines. Classical liberalism rests on a much more foundational and important insight about the central role liberty plays in enabling us to lead good, fulfilling, and meaningful lives. For classical liberals, liberty is not an end in itself, nor a licence for egoism and hedonism.

Liberty is the prerequisite of a good and meaningful life and the base condition on which human flourishing is built.

A central feature of the good life is that it is a life one chooses for oneself. While human diversity means that there is no single template for what the good life looks like, in order for us to lead good, meaningful and happy lives, we must be the agents of our own destinies and the authors of our own stories. Put simply, a good life is one that is freely chosen. It cannot be any other way.

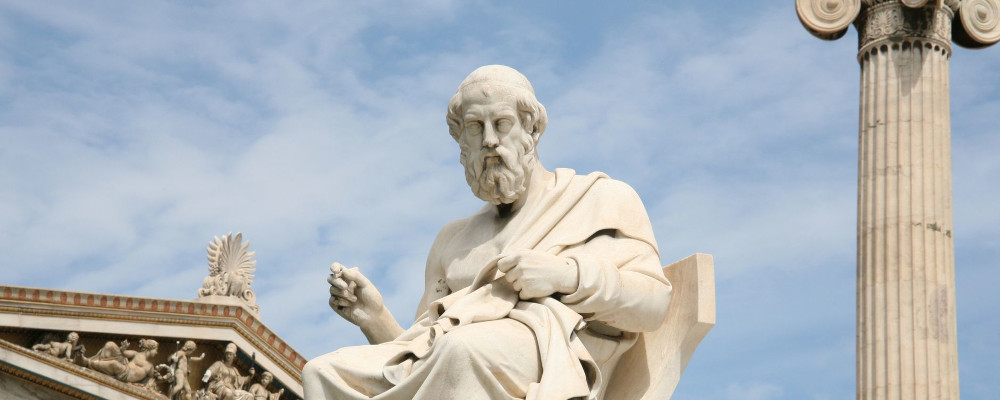

The connection between liberty and the good life is not just a concern for us classical liberals and moderns; it was a central concern of the ancients as well, including philosophers like Plato. But ancients and moderns had a fundamentally different understanding of what it means to be free.

For a philosopher like Plato, freedom is not open-ended. Platonic and ancient freedom was intrinsically connected to justice itself.

The good life for Plato is the just life. Only a man who is just is truly free. And justice, for Plato, is fundamentally about the soul. Specifically, it is about Plato’s famous tripartite account of the soul: the harmony and proper ordering of reason, spirit, and appetites. Reason and spirit rule over our appetites so that, unlike animals, we are not consumed and enslaved by our appetites and passions. These different parts of the soul work in harmony together and produce a well-ordered soul that orients us toward the good.

This seems very strange to the modern mind. By Plato’s account, we are only free when our souls are ordered in a certain way. A well-ordered soul that seeks to do good and be just is free; anyone else is essentially enslaved to their appetites or passions. For Plato, freedom does not enable us to lead good lives; we are only free when we seek the good. This is an important distinction and one that classical liberals reject, for good reasons.

Plato’s account of freedom is useful to us because it helps illustrate something important about the foundations of classical liberal liberty. Plato’s account assumes a homogeneity of persons that is both untenable and deeply counterintuitive to us moderns. It assumes that there is a uniformity amongst us and what is good, meaningful, and makes us happy is the same for all people. Classical liberalism rejects this and builds an account of human meaning on the opposite assumption — namely human heterogeneity and diversity.

The Platonic and ancient account of freedom can be understood as a kind of training process. It says you must learn through moral training how to be just, which is the only way a truly free person would want to behave. But in contrast, the classical liberal idea of liberty is best understood as a process of discovery. It is discovery, not training, that enables us to lead good and meaningful lives and allows us to be the agents of our own destinies.

People cannot be taught what gives them meaning and purpose; they must ultimately discover this for themselves.

In On Liberty, the British philosopher John Stuart Mill offers one of the seminal defences of liberty and the good life as a discovery process.

Mill argues for “freedom of character.” He says that it is best, both for individuals and society as a whole, that people have the freedom to develop their own character, to discover who they are and want to be. This is necessary, he argues, because every individual is unique, and there is not one single unitary human nature:

“Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.”

We all have different proclivities, interests, aptitudes, talents, passions, goals, and so on. We are all driven by different things. In short, we all have different natures.

How these natures are formed and shaped is a complicated question, but given the fact that human beings have such different and varied natures, people need the space to be able to develop and discover what it is that they most cherish and desire. People cannot be taught what gives them meaning and purpose; they must ultimately discover this for themselves.

Meaning and purpose look different for everyone; we cannot impose it. It’s not something predetermined that people can simply be trained for. But Mill doesn’t just argue for this kind of freedom out of necessity; he makes clear that a crucial component of the good life is that it be a life one chooses for oneself:

“It is possible that he might be guided in some good path. But what will be his comparative worth as a human being? It really is of importance, not only what men do, but also what manner of men they are that do it.”

This might seem so obvious to us that it isn’t even worth pointing out. Of course, a central feature of a life that is meaningful and purposeful is that we have ownership over it — that we choose it. But when contrasted with the ancient account of liberty, this seemingly basic fact is actually a crucial classical liberal insight we now take for granted.

Living freely is a prerequisite for a good and meaningful life because we draw meaning from our volition and the choices we make. And for these choices to help ultimately give us meaning, they must actually be meaningful. They must matter. This means we have to be left to face the consequences of the choices we make. When we are not left with this kind of freedom, we are not treated like adults but like children, infantilized and sheltered from the consequences of our actions, which renders these decisions ultimately trivial.

Ownership of our own choices, and of our lives, is at the core of classical liberal liberty. But it isn’t just an axiomatic claim. The brilliance of this now-obvious (to us) insight is that this kind of freedom is actually a central feature of the good life and helps produce happy and flourishing human beings. And while this might be an insight gifted to us by the philosophers, it is one that has been confirmed by modern psychology as well. The famed psychologist Nathaniel Branden, who was a pioneer of the self-esteem movement and also, for a time, a close associate of pro-market philosopher-novelist Ayn Rand, wrote:

“As a psychologist, I am keenly aware that in working with individuals, nothing is more important for their growth to healthy maturity than realizing that each of us has to be responsible for our own life and well-being, for our own choices and behaviour, and that blaming and dependency are a dead end; they serve neither self nor others. You cannot have a world that works, you can’t have an organization, a marriage, a relationship, a life that works, except on the premise of self-responsibility… We must take responsibility for our own lives and be accountable for our own actions. There is no other way for a civilized society to operate.”

We can only discover the good life when we are free to do so.

The accomplishment and esteem that we feel when we own our own decisions and take responsibility for our lives is not something that can be given to people; it is something people must earn for themselves. All that is needed from us collectively is that we give people the liberty to do so, that we don’t interfere with people’s choices and decisions unless it is absolutely necessary. When we have a society that provides and protects this minimal framework, we have given people the conditions necessary to flourish and find meaning. And it turns out that when we give people this liberty, they thrive.

In an essay series called “The Psychology of Freedom,” Dr. Sharon Presley, a social psychologist, writes that psychological research is rich in insights about the problems and issues of a free society.

It suggests what helps create psychologically healthy and autonomous individuals and why the need for individuals to be free is important. It warns us about what problems freedom faces and yet encourages us to understand that human nature is not, in fact, evil.

She argues that research on self‐determination, autonomy, and positive psychology shows that freedom is good for people.

They are healthier, happier, more motivated, and more in control of their lives under conditions of freedom. People thrive when they are free.

Giving people the freedom to govern and shape their own lives ultimately means giving both political and moral primacy to the individual.

The classical liberal defence of the individual is not about defending amoral self-interest; it’s about recognizing that freedom and dignity is inseparable from our status as individuals. The psychological characteristics of individualists have been explored in depth by psychologist Alan Waterman in his book The Psychology of Individualism. Waterman convincingly shows that people he deems “individualists” are less likely to suffer from the kinds of debilitating mental states and challenges that can cripple us — conditions like anxiety, depression, and alienation. Like Branden, he found support for a relationship between self‐acceptance/self‐esteem and qualities of personal identity and internal locus of control.

Individualism is not about treating people as isolated automatons, as is sometimes suggested; individualism actually helps ensure that our relationships with others are more meaningful.

We don’t choose our parents or where we come from, but our status as individuals does ultimately provide more meaning to our relationships with others. Part of being a free individual is choosing who to associate with. We are social creatures, and friendship and other relationships are a crucial part of our well-being. It’s a strawman to suggest classical liberals think otherwise.

Part of what makes many of these relationships so meaningful is that they are freely chosen. Take friendship: if we were simply assigned friends at birth, friendship would mean something very different. The fact that we choose our friends endows dignity and fulfilment on these relationships. You are friends with people because you want to be friends with them, and vice-versa. These freely chosen relationships have meaning precisely because we decided upon them; they were not imposed on us.

Classical liberalism is not just an approach to public policy and economic questions. It is a deep philosophical tradition built on foundational philosophical insights that we today often assume without even realizing. So much of what I have sketched out here seems very basic to many of us, yet it is important to appreciate how radical and deep these commonly accepted insights are.

We value liberty because we recognize that liberty is a prerequisite to the good life.

The good life cannot be prescribed for us; it is something we must discover for ourselves. Our diversity and the variety in human natures means people must be given the space and freedom to discover themselves and what gives them meaning. But this process of discovery and the self-esteem, authorship, and sense of responsibility and ownership it produces in people is precisely what leads to human flourishing. Liberty and the good life are not antithetical; they are inseparable. We can only discover the good life when we are free to do so, and our choices and lives can only produce meaning when they are genuinely free choices.

We must cherish our liberty and protect it, precisely because our flourishing and happiness is impossible without it.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Peter Menzies: The mainstream media should love Doug Ford, now that he’s subsidizing them

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by