President Lyndon Johnson reportedly said that Gerald Ford was so dumb that he couldn’t walk and chew gum at the same time. Canada will have to do both as it crafts a China strategy in the shadow of the growing competition between the United States and China.

The relationship between the United States and China will be the scaffolding of the international order that emerges from the ashes of two global events that bookended the last decade — the global financial crisis and the pandemic. These last ten years have played to the relative advantage of China — a financial crisis that started in the United States and went global, and a global pandemic that started in China and was then horribly mismanaged in the United States. American own goals at the beginning and the end of a decade enabled China to gain rapidly on the United States. But the game is far from over.

The United States has never faced a challenge like the one it faces now from China. The analogy to the “cold war” with the Soviet Union is a poor fit because the Soviet and American economies were barely connected. The two powers competed intensely, but on a narrow band of security and ideological issues. The broad competition between China and the United States is of an entirely different order.

China is a significant economic competitor. Its economy is growing fast in the part of the world that is growing the fastest. China’s economy is already larger than that of the United States in purchasing parity power and will likely overtake the American economy sometime in the next 15 years. In this last decade, China has become the largest trading partner of 100 countries, while the United States is the largest trading partner for only half as many. Beijing has also invested trillions of dollars in infrastructure all over the world through its Belt and Road initiative and an equivalent amount in building digital infrastructure powered by its national champion, Huawei.

In this past decade, China has emerged as an innovator and a leader in many of the technologies that will shape the next twenty years. Its companies — Alibaba, Tencent, and Huawei — now compete with the best of U.S. companies and lead in digital payments and integrated platforms. China currently lags badly in semiconductors, but is investing massively in robotics, biotechnology, quantum computing, and advanced artificial intelligence. In many of these next-generation technologies, China is already a formidable rival to the United States.

The gifts of this last decade enabled China to close the gap with the United States much more quickly than its leaders expected. Beijing nevertheless faces big challenges that can get in the way of its ambitious plans. Its population is aging rapidly and will peak in the next few years. Its population could shrink by half a billion over the next several decades and the number of workers per retiree is expected to decline dramatically. All of this leads to reduced productivity and slower growth at a time when China’s debt is now over 300 percent of GDP. At the National People’s Congress last month, Xi Jinping promised annual growth of around 6 percent, a sharp reduction from the sizzling growth of the last several decades.

At home, China is cracking down harshly on even mild dissent and is engaging in genocidal actions against its Uighur population. It has suppressed the remnants of democracy in Hong Kong and ratcheted up the pressure on Taiwan.

China is also increasing its defense spending more quickly than its GDP is projected to grow as it tries to establish itself as the undisputed hegemon of Asia. It has asserted expansive rights in the South and East China Seas, accelerated its border skirmishes with India, and grown more strident in its dealings with Australia and Canada. This far more assertive posture is consistent with Xi Jinping’s conclusion that China is rising and the United States is in decline.

Ottawa may have preferences, but little in the way of meaningful choice.

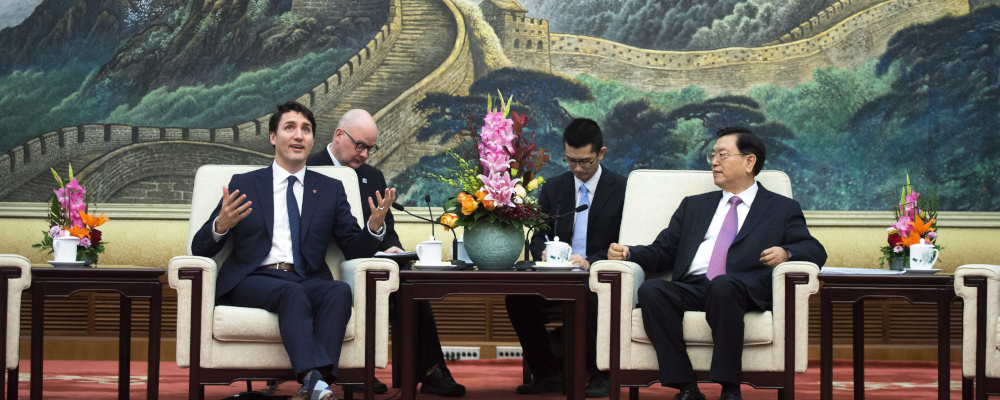

A newly assertive and dynamic China challenging the United States head-on is uncharted waters for the United States and its closest allies. The Biden Administration has yet to define its strategy toward China as it rebalances from the shambolic Trump presidency. What strategy it ultimately chooses will be of enormous consequence for Canada.

Canada will have to choose between two broad strategies.

In a world where globalization is retreating, supply chains are shortening, and resilience has become more important than efficient just-in-time delivery, Canada is more dependent on access to the U.S. economy than it ever has been. It is conceivable that this new world order will push us over the line into an integrated North American economy. We can already hear rumblings in discussions of integrated markets for electric vehicles, vaccines, and essential goods. In this world, Canada contracts out its China policy to Washington and is first in to Biden’s coalition of willing democrats. If the Biden Administration opts for a hybrid of containment and collaboration, so much the better. That option leaves the door open for progress on climate change, global health governance, and modernization of the trading system, all issues that matter to Canadians. If it opts for confrontation, so be it. In an increasingly integrated North American economy, Canada has little choice but to get in line with whatever strategy the United States chooses. Ottawa may have preferences, but little in the way of meaningful choice.

At the other end of the spectrum, Canada continues to plead for exemptions from U.S. protectionism and does what it absolutely must do but no more to accommodate the United States. Ottawa then makes a sustained effort to grow its trade with China and other Asian markets. It walks softly and carries a small stick, all in the name of the preservation of the autonomy Canada still has in a world that is regionalizing. Ottawa stays out of the headlights of the U.S.-China competition and reaps marginal advantage whenever it can.

Neither strategy is cost free. That Canadian public opinion has swung massively against China is an important constraint on the second option, at least for the short-term. Nor will Canadians cheer the creation of truly integrated North American markets and the contracting out of policy. That is a constraint on the first option.

Likely then, our government will mix and match, cherry picking the elements from each that best promote Canadian interests and leave Canada some voice on values. Whatever the mix and match, Ottawa will do far better acting in concert with others than alone.

As a perennial pragmatist, Canada will have to be extraordinarily proficient at walking and chewing gum at the same time.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Peter Menzies: The mainstream media should love Doug Ford, now that he’s subsidizing them

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by