Defined as a political regime in which the people rule, populism seems to be growing in many countries. However, opinions on populism often ignore a basic question: who is “the people”? Over the past 50 years, economists and political scientists have demonstrated that “the people” as a governing agent does not exist. Although the topic may appear abstract or theoretical, it has momentous practical implications for how to interpret election (or referendum) results.

The reality is that “the people” does not exist except as a collection of individuals with different preferences and values. Only on very few issues (a minimum of public order, for example) is there presumptive agreement among all members of a society. Should more milk or more cars be produced, and in which quantities? Who should earn more? On such questions, it is difficult to find many individuals sharing the same opinion. Saying that the people should rule or govern thus means, in practice, that a subset of the people will rule over another subset of individuals whose preferences and values will be violated.

The elusive will of the people

People (the individuals who make up “the people”) can govern through elections (including referendums). However, it has been shown that voting results do not represent what “the people” wants. The results can be as incoherent as if “the people” are irrational. This fact was first discovered by Nicolas de Condorcet, an 18th-century French philosopher and mathematician, and has since been the object of many mathematical confirmations and elaborations. It is called the “Condorcet paradox” or the “paradox of voting.”

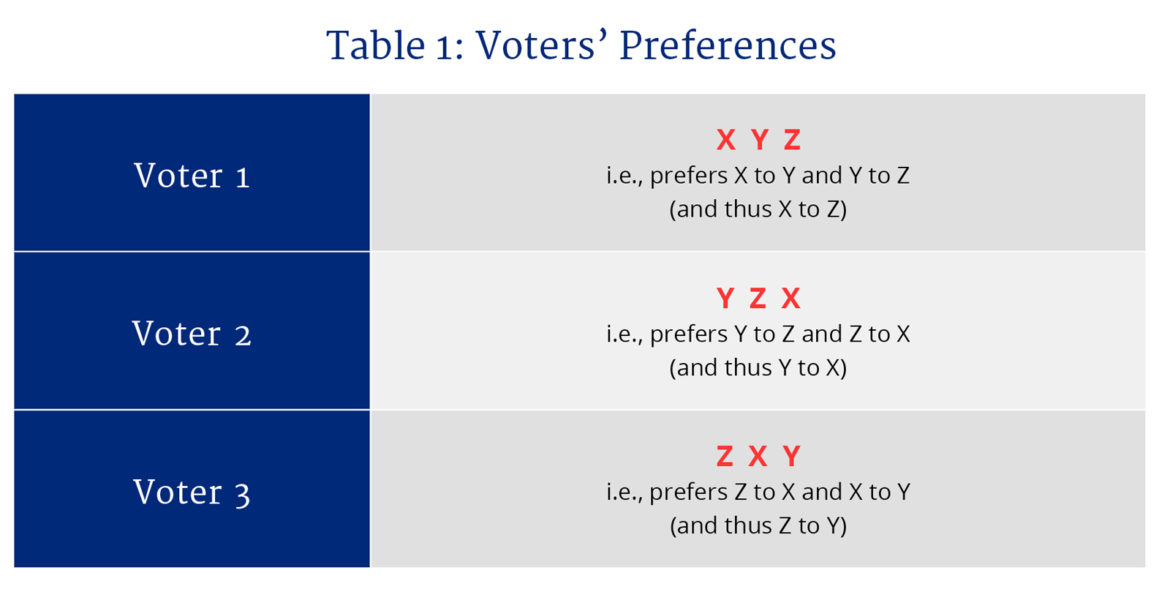

To illustrate, consider an electorate composed of three voters, Voter 1, Voter 2, and Voter 3; and three policy options, X, Y, and Z (such as, for example, an employment subsidy, increased family allocations, and a higher minimum wage). Table 1 shows the hypothetical preferences of the three voters. Voter 1 prefers X to Y and Y to Z; hence his ordering can be represented as “X Y Z.” If this voter is coherent or rational, he prefers X to Z—that is, his preferences are assumed to be “transitive.” Voters 2 and 3 have different preferences, which are also transitive.

Now suppose that the three voters are asked to choose between X and Y. Given their preferences, it is easy to see that X will win with two-thirds of the vote because both Voter 1 and Voter 3 prefer X to Y (see Table 2). If the choice is between Y and Z (perhaps in a subsequent election), Y will win. But if the alternative presented to the voters is between Z and X, it is Z that will win. The electorate prefers both X to Z (as the first two elections imply, through the transitivity property) and Z to X—a clear contradiction.

Despite each individual voter being rational, the aggregation of their votes is not. An incoherent majoritarian cycle will occur even if no voter changes his or her mind. We cannot know what “the people” wants. “The people” does not exist as a rational chooser.

If we modify the hypothetical preferences of our three voters, certain configurations will avoid the Condorcet paradox. However, the more voters there are, the more likely the paradox will mar voting results.

One empirical confirmation of this phenomenon was observed over seven days in January 1925. With only one senator changing his mind (or being incoherent), the U.S. Senate voted to refer a hydroelectric project to a study commission (X) instead of allowing private development (Y); to support private development (Y) instead of public ownership (Z); and then, finally and inconsistently, to approve public ownership (Z) instead of a study commission (X).

It would not be surprising if, as in the old jest, the Quebec electorate once literally favoured (and perhaps still favours) “an independent Quebec in a united Canada,” even if each individual voter had coherent preferences.

A crucial discovery was made when Kenneth Arrow, then at Stanford University, mathematically demonstrated that the Condorcet paradox generalizes to all voting methods that respect a small number of simple axioms (such as transitivity of individual preferences, non-dictatorship, and independence of irrelevant alternatives). He later won a Nobel Prize in economics. To simplify, Arrow’s “Impossibility Theorem” established that the result of a vote is either irrational (somewhat like in the Condorcet paradox) or dictatorial in the sense that one individual’s preferences win, whatever other individuals’ preferences are.

Thus, the people cannot rule. You either have an irrational people (in the aggregate) who rule, or else a dictator (of the right or the left) who claims to embody the so-called “will of the people.” To feed the illusion that there is one unified people, a populist leader has to find “enemies of the people” that are defined out of the people he claims to represent. History provides multiple illustrations of this.

Other problems exist as well. Notably, different voting methods can produce different results. So, too, can control of the agenda to determine which alternatives are put before voters.

What democracy is good for

There is one sense in which populism would be possible: if it is defined as a political regime in which, as much as possible, each individual citizen governs himself—“self-government” literally. However, there is already a label historically associated with such a political philosophy: classical liberalism, as represented by theorists of limited government such as Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, James Buchanan, and many others.

Populism as commonly and historically understood is an exaggeration and corruption of democracy. Democracy is a good way of changing the political personnel in government. But it does not say anything about what “the people” wants; it just reveals whether a majority, the current one, is or is not satisfied with the current government. This is useful enough, and this is the democracy that is realistically possible.

Recommended for You

Ginny Roth: J.D. Vance, Pierre Poilievre, and how they slice their economic pie

David Polansky: As President Biden leaves the race, will the Democratic Party hodgepodge hold?

Peter Menzies: The mainstream media should love Doug Ford, now that he’s subsidizing them

Geoff Russ: A future Conservative government must fight the culture war, not stand idly by