In-demand occupations and top-hiring companies certainly reflect the demands of everyday life, and right now we can see a few trends emerging as we approach the holidays. With warnings of supply chain issues, and perhaps an eagerness to make up for last year’s lost holiday season, retail saw an increase in hiring in October. Did it stay that way in November? Are there other issues at play? This month we’re taking a look at how the nuances of the 2021 holiday shopping season have impacted hiring. The analysis draws from Workforce WindsorEssex’s unique data source which covers job postings from across the province (excluding the City of Toronto and the far north-eastern region).

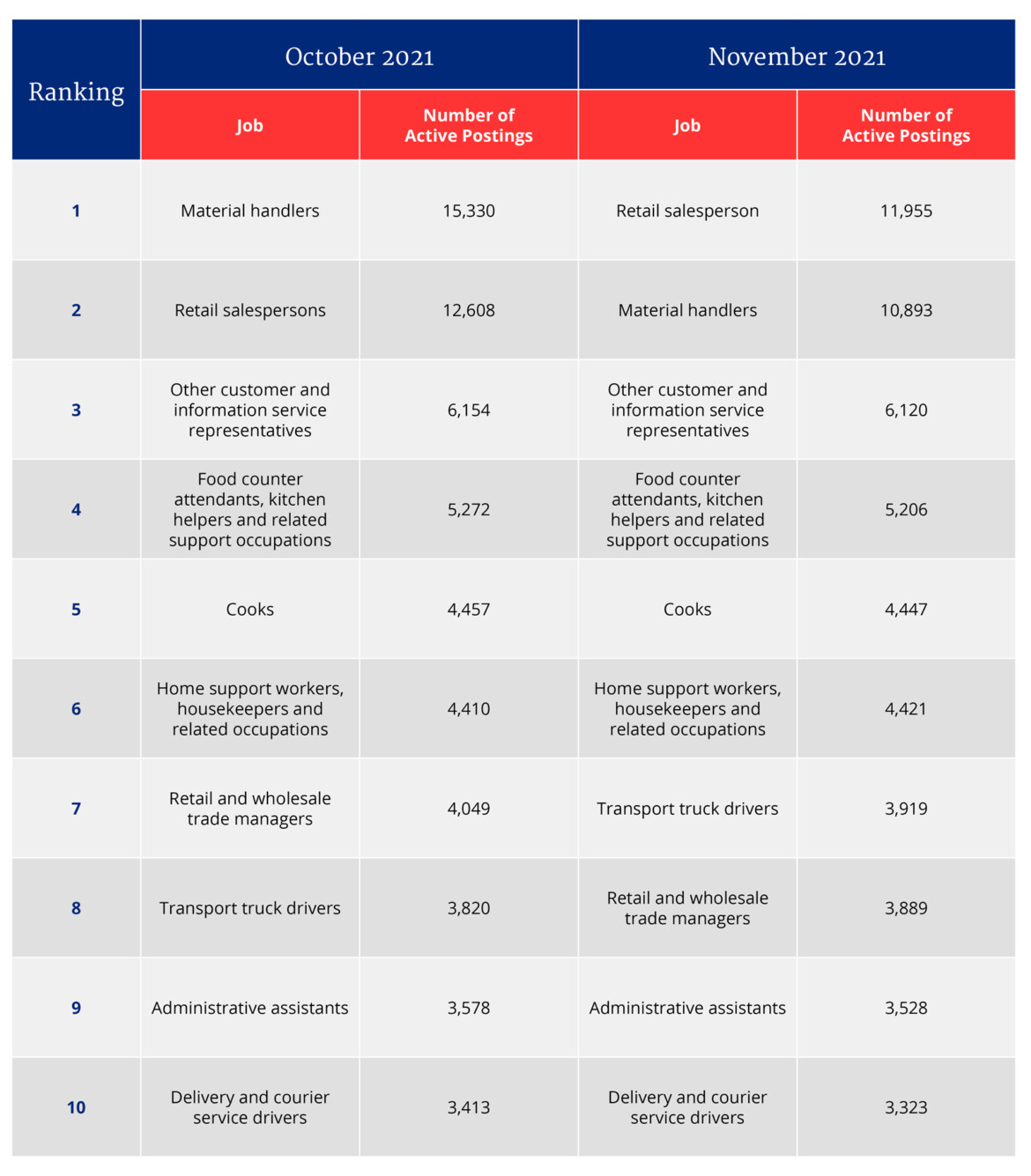

The 10 most in-demand occupations in November 2021 compared to the previous month were as follows:

The top-10 in-demand occupations constitute just under one-third of all job postings (57,701 job postings or 31.2 percent) in the regions. The number of active job postings decreased by 2,573 in November relative to October for a total of 182,267, compared to 184,840 active job postings in October. This is a decrease of 1.4 percent across the regions for November.

We did see a decrease in hiring in some of the top-10 in-demand occupations from October to November. Most notable is the 28.9 percent decrease in hiring for Material Handlers, from 15,330 total active job posts in October to 10,893 in November. Retail Salespersons job postings are also down 5.2 percent from 12,608 total active job postings in October to 11,955 in November. Both of these figures are, however, closer to what they were in September (11,935 total active job postings for Material Handlers and 11,690 total active job postings for Retail Salespersons).

The increase in job postings for Material Handlers and Retail Salespersons in October is connected to retailers preparing for their Black Friday sales in November. This kicked off an earlier holiday shopping season, with many shoppers eager to make up for the lost holiday season of 2020 due to the pandemic. In fact, the Retail Council of Canada noted that Ontarians estimated they will spend $863 during the 2021 holiday season versus the national average of $792 as part of their 4th Annual Holiday Shopping Survey.

On the other hand, demand for Transport Truck Drivers increased 2.6 percent in November from October. Transport Truck Drivers are employed in the Transportation and Warehousing sector by businesses in transportation, manufacturing, distribution and moving companies, or they may be self-employed. To accommodate a busier shopping season, many companies, especially those on the top-10 hiring companies list below, would need additional employees at this time of year. In fact, looking at Statistics Canada’s employment by industry for the whole of Ontario, there were 382,500 employed in the Transportation and Warehousing sector in November, up 1.5 percent from 377,000 employed in the sector in October. This is also up 10.4 percent from 346,400 employed in November 2020, but not quite at pre-pandemic levels (down 3.7 percent from 397,100 jobs in November 2019, as a reference).

The top-10 companies hiring were as follows:

While the companies on the top-10 list remained the same (with some changes in the top-10 spots), most decreased their hiring. Companies typically hire in advance of the holiday season so their recruitment process, hiring, and onboarding and training would be completed before they get extremely busy. As well, we are seeing well-publicized supply chain issues this year, sparking a sense of urgency in shoppers. With employers beginning their hiring process in October so the workforce can be in place before November, it was anticipatable that job postings would start to reduce.

The Home Depot Canada tops the hiring companies chart with 2,635 total active job postings, up 21 percent from 2,083 in October. The Home Depot Canada carries many seasonal items and as well, many people may be looking to continue home improvements and other projects at home as the pandemic continues.

Also notable is the 16.7 percent increase in McDonald’s Restaurants’ hiring. This could be in preparation for increased business due to the holidays and already having the infrastructure in place to accommodate food orders quickly for drive-thru, take-out, and delivery options in the event additional public health measures are put back into place to address rising COVID-19 cases, as well as to cover vacation for some of their regular year-round employees. In addition to this, McDonald’s Restaurants is likely experiences a high turnover rate.

Looking ahead to December, we may see reduced job postings across Ontario as the holiday shopping season will have concluded and employers would not typically begin the recruitment process for any open positions in December, especially employers who either close or reduce capacity between the Christmas and New Years period.

For more information about Workforce WindsorEssex and their valuable LMI, please visit workforcewindsoressex.com.

Recommended for You

Sean Speer: Investing in critical minerals isn’t just good business, it’s a national security imperative

Michael Kaumeyer: Polite decline: Canada’s aversion to being our best is holding us back

‘Nobody cares who your daddy is’: John Whittaker and Rahim Sajan on what makes Alberta attractive to dreamers, strivers, and entrepreneurs

Women’s economic outcomes are improving—but what’s happening with men?