While the evidence may be in short supply these days, everyone does, in fact, have a brain. Understanding what they are and how they actually work is an essential task when trying to assess what’s going on in the world and with the people who inhabit it. Attempting to do just that, neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett has written a fascinating book on the subject, Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain, in order to demystify our body’s most essential component.

The Hub’s executive director Rudyard Griffiths recently sat down with Barrett for a Munk Debates Dialogue to discuss how our brains operate, the societal problem of stress, the fact that our nervous systems are socially dependent, and the importance of training your brain the same as you do your body.

You can watch the full discussion below or on YouTube. An edited transcript focused on the parts of the conversation dealing with politics and polarization is available below.

This conversation has been revised and edited for length and clarity.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Thank you, Lisa, for spending some time with me today. I want to begin with having you extrapolate for us what you’ve learned from your extensive physical study of how the brain actually works. What insights can we draw from your work to better understand how we interact individually and collectively? What is actually going on in our brains when we reason with each other?

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: There is so much to say about this.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Take your time—that’s why we enjoy this format. We are not doing a five-minute cable interview. You’ve got time to expound on your thinking and ideas. So, please go ahead.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: One important thing to remember is the most expensive things that your brain can do are move your body, like exercise, right? And learning something new. Learning something new is expensive. And I think everyone has maybe an intuition about this because if you’re working really hard to learn something new— like you’re working in school or you’re working hard to learn to play the piano or you’re working hard to learn some skill—there always comes a point where it’s kind of unpleasant. You’re tired, you’re struggling, and you have to really push through that. It’s true with exercise; it’s true with learning. It’s also true with engaging with people who have deeply-held beliefs that maybe don’t match yours. So, that’s the first thing to understand.

The second thing to understand is that—so, let me just back up and say, so feeling unpleasant doesn’t mean something’s wrong necessarily. It could just mean that you’re working really hard at something.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Good point.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: And you have to really push through that. The second thing to understand is, remember how I said that uncertainty is expensive? And so, one way that we engage with each other is to manage that predictability.

So, if I make myself predictable to you, then you are more predictable to me and everybody’s brains kind of benefit from that, right? But if you are unpredictable, if I can’t predict what you’re going to do next or say next; if you look different from me; if you sound differently for me; if you smell differently from me; if you have different ideas than I do; if I’m just largely unfamiliar with you, I’m not going to be able to predict as well. And that is going to increase uncertainty for both of us, which is going to increase the unpleasantness of the interaction, potentially.

Because really the truth is that people love novelty when it comes to food and clothes and all kinds of things, except when it comes to each other. When it comes to other people, humans tend to gravitate to similarity, to people who love the same way they do, or behave in predictable ways, or have the same beliefs and values. But that may be comfortable in the moment, but it’s not necessarily the best way to conduct your life. Just like to be healthy, you exercise. So, you deliberately expend energy; you deliberately try to dysregulate your body, so that your brain can find a way to get itself back into a good regulatory state.

So, your brain throws itself out of regulation in order to work hard to get back into a good state, as long as it replenishes what it spends. And similarly, I don’t know about you, but I’ve lived in Canada for a number of years, and every year at the first snowstorm, I would get into my car and I would deliberately put myself in a tailspin so that I could try to remember muscle memory, how to get out of it automatically.

We often will invest energy, spend energy, actually put ourselves in uncomfortable situations to learn something new so that we can predict better automatically in the future so that we cannot just survive but thrive. And that includes engaging with other people who maybe believe different things than we do, because there may come a time when that information would be really useful to you.

You can look at discussions about democracy, for example, as a great human invention harnessing the sort of value and productivity that comes from debate. So, in a sense democracy, which requires engaging with people and arguing and debating, sometimes great insights and great solutions come out of the fires of intense debate. And that’s one of the founding ideas behind the value of democracy, and that means that there’s a certain amount of discomfort that comes along with democracy. It’s sort of like the price of democracy.

As Anne Applebaum, a historian—I think it was Anne Applebaum who said that discomfort in engaging with ideas that are different from yours is one of the prices that you pay for democracy. Or if she didn’t say it, then maybe I said it in response to something she said, but basically, I’m giving her this insight, and it’s a really important insight.

You never know when a piece of knowledge is going to be useful to you, more generally, to solve a societal problem. Just in the same way that animals forage for new sources of nutrients, we forage for information. And some of that information comes from other people who maybe we in the moment disagree with intensely, so, there’s a value there.

There’s also a value just in terms of our own day-to-day health. I haven’t lived in Canada for a long time now, but in the United States, there are tremendous ideological disagreements to the point where people are demonizing each other. Really, it’s very serious for a number of reasons, but one of the ways it’s very serious is that it’s probably contributing to a public health problem.

Half the country felt disenfranchised when Trump was president and found it really stressful to have him be president. What is stress? Stress is just your brain preparing your body for a major metabolic outlay because it can’t predict well or it’s predicting something. They have to do something or learn something, or there’s so much uncertainty that your brain is basically trying to prepare for multiple possibilities. And that’s really all stress is. So, there can be good stress where you learn something and you replenish what you spend.

And then there’s bad stress, chronic stress where cortisol, for example, is not a stress hormone, it’s a hormone that gets glucose into your bloodstream quickly because your brain predicts that you have to either learn something quickly or do something quickly. And so, it’s a hormone that is secreted during a major stressful event, but it is also secreted when you drag your butt out of bed in the morning because that’s also a metabolic event. So, half the country was chronically stressed when Trump was president. But for the four years before that, or maybe even the eight years before that, the other half of the country was chronically stressed when Obama was president.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: And you’re saying that chronic stress is born out in real physical illness? It’s not just simply a mental state of stress?

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: Yeah, so there is no mental state of anything which doesn’t have a biological basis. And the important thing to understand, health or anything to do with regulating your body illness, is that there’s rarely a single cause. Usually, there are multiple causes; they’re all kind of working together in an ensemble, like a blanket of cause, if you will. And so, if your energy regulation, if your metabolics, is inefficient or you’re living in chronic stress, meaning there’s a lot of chronic uncertainty, you’re basically paying a little metabolic tax. Not a huge tax, but a little one. And those little taxes add up over time and predispose you to some kind of metabolic illness, and metabolic illnesses are rampant in our society. Not just diabetes and heart disease, certain types of cancer.

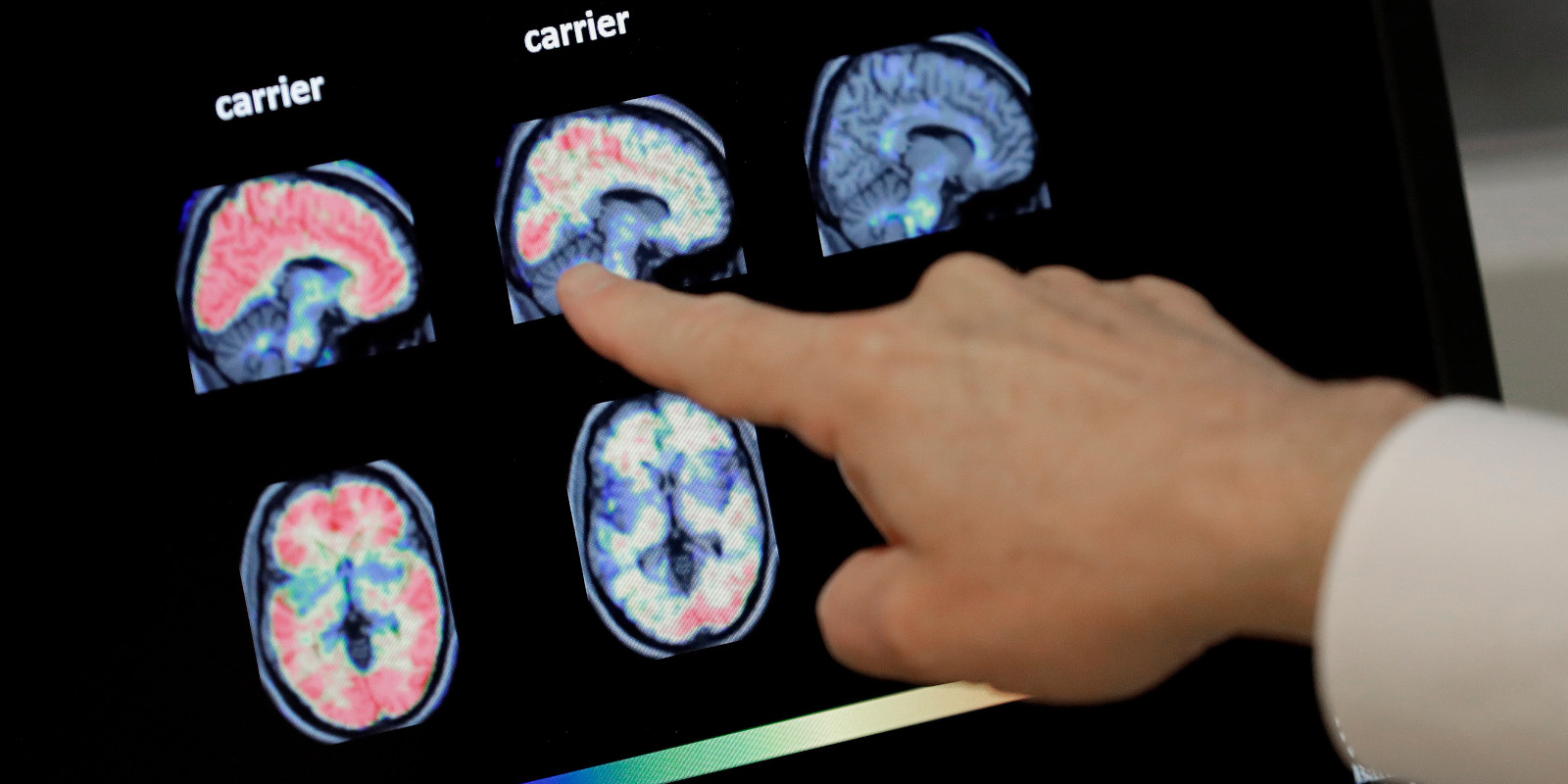

Depression is a metabolic illness. It’s an illness also that involves your immune system. It’s really a whole system set of problems. But metabolism is a key feature that has been overlooked for a long time. Anxiety, even Alzheimer’s disease and dementia have a metabolic basis to them. And again, I’m saying not reducing everything to metabolism. I’m just saying this energy regulation is one key feature; one key factor in a larger kind of ensemble or blanket of factors. And if your environment is very unpredictable, chaotic even, if you can’t make yourself predictable to others, they’re not predictable to you.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: You’re living in a polarized tribalized society like we are today then you’re going to incur these metabolic costs.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: You absolutely are. And so, what do you do when you’re running a deficit in your bank account? You stop spending. What does the brain do when it’s running a deficit in its body budget? It slows its spending. What is slowing your spending mean? It means you’re fatigued. It means you don’t want to move as much, literally. You are lethargic; you have apathy. It means that you’re not learning as well, that you actually avoid people and conditions that are novel, and that’s a problem. So, this was the situation that we were in before COVID-

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Then add COVID to that, right?

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: And add COVID to that, but you know what—

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: The stress and the cortisol goes right through the roof.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: Yeah, and here’s the thing that nobody’s talking about really. I mean, when they’re talking about it, they talk about people; talk about it justifiably in terms of certain segments of the population being more at risk for infection. But the way viruses work, most viruses, there are a number of factors that influence whether or not a virus can take root essentially in your cells and cause infection. So, there are these really classic studies done more than a decade ago where they took people and sequestered them in hotel rooms—this is work by Sheldon Cohen at Carnegie Mellon University and a whole slew of colleagues, takes people, sequester them in hotel rooms, control everything about what they eat and how much they sleep and so on. They place a virus, and in one study was a coronavirus—not the COVID virus but another variant of a coronavirus—and they place the virus in the person’s nose and they’re controlling viral load here. Depending on the study, only 20 to 40 percent of people develop respiratory symptoms.

The point is that a virus is a necessary cause, but it’s not a sufficient cause of illness. The state of your immune system; the state of your own metabolism, which is related to your immune system; the state of your brain, these are also necessary, but not sufficient conditions, right? So, there is no simple single cause of illness in most cases. It’s possible that if you’re exposed to a viral load, like you’re basically bathed in an environment of the virus, a high concentration of the virus will overcome even a very robust immune system.

But the fact is that most people, certainly people who are disadvantaged in our society but actually also everyday citizens across the country—not just people who are subjected unfortunately to adversity—basically just a wide swath of the population began the COVID pandemic in a state probably where their immune systems were somewhat compromised. So, when I say this, I want to make it really clear. I’m not minimizing first-line workers or people who live with adversity. I’m not minimizing the burden that—

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: The additional stresses.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: Yeah. I’m just saying that the stress didn’t begin with the pandemic, it began before that. I read in The New York Times a couple of weeks ago about how people are feeling exhausted because they’re on their fight and flight, circuits are so overloaded and I’m thinking, “That’s not at all what it is.” What it is, is that we’re living with tremendous uncertainty and so brains aren’t predicting well. And the uncertainty isn’t just about the virus. It’s about people’s behaviours in response to the virus.

If I go to the store, if I go to the supermarket, are people going to be wearing their masks correctly? Do I have a close friend who’s having a birthday party for their kid and they want me to come, and I think it’s unsafe? All of these things are actually small little instances, but they add up over time to cause big problems, including putting democracy at risk.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: It’s fascinating stuff. I want you to reflect on the insight that people’s words have a direct effect on your brain activity, and your bodily systems and your words have the same effect on other people. Do we have some kind of duty of care, Lisa, to each other? A kind of a neurological responsibility to understand that words, as you’ve just talked about, create these metabolic responses; these reactions in the brain that are literally harming each other through how we interact with each other?

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: Yeah, so as a scientist, I’m going to answer this question in two ways. I’m going to answer it in the scientific way and then I’m going to take my lab coat off and answer it in a more personal way. So, as a scientist, what I can tell you is we live in a world where we really prize individual rights and freedoms, but we have socially dependent nervous systems. I mean, scientists don’t like to use the F word “fact,” but that’s about as close as to a fact as I can probably think of. We influence each other’s nervous systems in ways we’re completely unaware of. And one of those ways is by using words.

I can text three little words to my friend who lives in Belgium. She doesn’t have to hear my voice; she doesn’t have to see my face, but with those three little words, I can change her heart rate, I can change her breathing, I can change her metabolism. People read the Bible, they read the Quran, they read poetry from the 14th century, and it can enrage them or it can soothe them, and there’s a biological basis for those feelings. So, like I said at the beginning of our chat, the same regions of the brain which allow you to understand and use words also regulate your body. That’s just there in the anatomy and this conflict that we live with is there, whether we recognize it or not. So, that’s me being a scientist. Now, I’m going to take off my lab coat and say I do think we have a duty of care. Every time, I get myself into a lot of hot water when I talk about this because people think that I’m somehow advocating against free speech, which I’m really not doing, but I am advocating freedom of choice and freedom of responsibility. That is, your freedom comes with a certain responsibility. I suppose you’re free to accept that responsibility or not, but because you have freedom, you also have responsibility. So, who do you want to be as a person? Do you want to be someone who adds a metabolic load to somebody else?

Well, sometimes you do, right?

I’m a professor, I have students, and sometimes I am actually adding to their metabolic load on purpose. I’m trying to teach them something new and maybe something that’s hard or something they don’t like or something that violates their deeply-held belief. And so, I’m trying to support them. It’s just like exercising with a friend, you’re throwing your body into a deficit position, but you’re doing it with someone, and so, that makes it a little bit easier.

But there are times when we don’t want to do that, and so sometimes people really react to this and they go, “Well, my words, aren’t really harming people.” And my answer is, “Your words are not going to immediately strongly cause someone harm, but they will contribute to harm for that person over a period of time, and that could happen. And is that who you want to be?”

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: And just for all of us to think, when we’re banging at those tweets or on a social media site like Facebook, I guess, Lisa, it’s not consequence-free. You are literally, as you say three words, you’re changing somebody’s metabolism; you’re possibly spiking their cortisol. You are having a direct physical effect in the same way. I don’t want to exaggerate here, but in the same way as if you reach out and push somebody.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: The point I think that’s important to understand is that over a period of time, and again, this is really clear in data, children who experience adversity are more vulnerable to metabolic illnesses in adulthood; adults who experience metabolic adversity in young adulthood are more likely to experience or more vulnerable to metabolic illness later in life. And the evidence suggests that bullying, verbal bullying, the calling names, the idea of “sticks and stones don’t break my bones, names will never hurt me,” it’s actually not true. It’s just really not true because the evidence suggests that verbal aggression over a period of time can have similar physiological causes to actual physical violence, which I know is shocking. And if I hadn’t seen the data with my own eyes, I’m not sure I would believe it either. I’m sure I’d be motivated not to believe it, but it is what it is.

We are social animals. We evolved to have socially-dependent nervous systems because for very good reasons. But those reasons also leave us vulnerable, leave us open to unforeseen negative effects. And so, one way that you can, I think, protect yourself in a sense from those negative effects is to engage mindfully and deliver with people who disagree with you, just the way you would exercise. Every morning, I throw my body, my brain, my body budget into a deficit position, and then I replenish afterward. That’s exercise. So, why would I do that? Because if there’s ever a time when you need to do something unexpected, but very physically strenuous, I’ll be in a better position to do that because I’ve made the investment in training my body.

You can do the same thing with your brain. So, in an ironic kind of way, mindfully and carefully engaging people who disagree with you is like exercise for your brain as long as you replenish. So, for example, during the last federal election here in the United States, I signed up to call people in states, that was going to deliberately put me in contact with people who probably disagreed with me so that I would have a chance to talk with them. And I did that throughout the entire election, partly because I felt like it was my civic duty, but also because I felt like it was a good exercise for my brain. It was a way to sort of engage with something stressful in a way that was under my control so that the rest of my life would not be so stressful every time I pick up a newspaper.

RUDYARD GRIFFITHS: Well, Lisa Feldman Barrett, thank you so much for the conversation. You speak as beautifully as you write, and I recommend to everyone that they get a copy of Lisa’s latest book Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain. Lisa, thank you so much for coming on the program. I really enjoyed this talk.

LISA FELDMAN BARRETT: Thank you so much for the invitation. It was really an honour.

Recommended for You

Adam Zivo: No Dr. Bonnie Henry, drug prohibition is not ‘white supremacy’

DeepDive: Two-parent families: why they’re so important—and why there’s cause for concern in Canada

Patrick Luciani: Does liberalism make us better people?

Alicia Planincic: Want to regain support for immigration? Prioritize economic immigrants once again