Ronald Reagan, Peter Thiel, and more—Matthew Continetti traces the history of American conservatism

This episode of Hub Dialogues features host Sean Speer in conversation with Matthew Continetti, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute and founding editor of the Washington Free Beacon, about his new book, The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism.

They discuss the history of American conservatism and its particularities, why populism will always be a component of the movement, and the intellectuals and leaders who have influenced the right, from Frank Meyer, William Buckley, and Bill Clinton to Ronald Reagan, Peter Thiel, and Donald Trump.

You can listen to this episode of Hub Dialogues on Acast, Amazon, Apple, Google, Spotify, or YouTube. A transcript of the episode is available below.

Transcripts of our podcast episodes are not fully edited for grammar or spelling.

SEAN SPEER: Welcome to Hub Dialogues. I’m your host, Sean Speer, editor-at-large at The Hub. I’m honoured to be joined today by Matthew Continetti, a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, founding editor of the Washington Free Beacon, and author of the important new book, The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism.

Let me just say I’ve been looking forward to reading the book ever since Matthew announced he was undertaking this ambitious project. I’m pleased to say that it doesn’t disappoint. I’m grateful to speak to him about the book and its key insights.

Matt, thanks for joining us at Hub Dialogues, and congratulations on the book.

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Thank you, Sean. It’s a pleasure to be here, and I’m so pleased to hear that you enjoyed the book.

SEAN SPEER: Your book follows in the footsteps of previous intellectual histories of modern conservatism by the likes of Russell Kirk, George Nash, Lee Edwards, and others. How does your book fit within this broader body of scholarship and popular writing? What were you hoping to achieve with this project that is separate or different from those who came before you?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Well, a few things. The first is that many of the books you mentioned tend to have a different frame of reference than my narrative. Some of them start at the end of the Second World War. Others trace American conservative thought all the way back to Edmund Burke as in the case of Russell Kirk’s conservative mind that you mentioned.

My book is a little bit different. What I do is I begin with the inauguration of Warren Harding in the spring of 1921, and I end with the inauguration of Joe Biden in January of 2021. And I did that because I thought it was necessary to show the pre-history of American conservatism, what the right looked like prior to the end of the Second World War when a self-consciously conservative movement came into being.

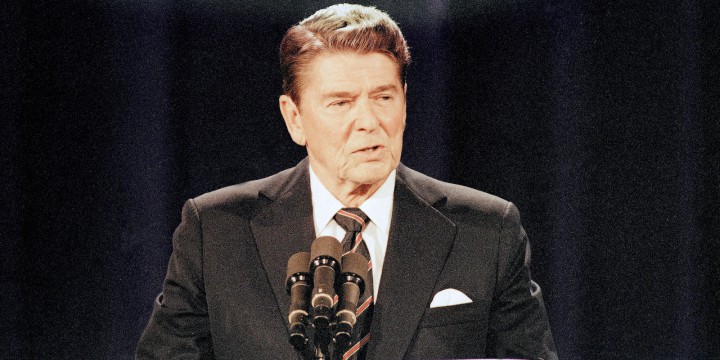

Another difference in my book is Ronald Reagan appears as a major character. It’s impossible to write the history of American conservatism without talking about Ronald Reagan. I tried to present him as simply one character among many others and it’s my feeling that in some ways, Reagan’s personality and also his political and electoral success, kind of warps people’s understanding of what the right in the United States has looked like, and ought to look like.

And then, finally, a difference between my book, The Right, and some of the other great books that you mentioned in your question is that my book is not solely an intellectual history. It doesn’t unnecessarily get into the weeds, the thickets of the subtleties of some of these thinkers. What it does is it tells a story of how writers and scholars and economists and public policy experts interacted with American politics, responded to American politics and influenced American politics. So, it’s a synthesis of the political and the intellectual, which you don’t find in a lot of the other histories of American conservatism.

SEAN SPEER: There’s so much there to unpack, Matt, maybe just start with this question. Why did you call it The Right? What does the descriptor “the right” capture that other nomenclature, like conservatism, or classical liberalism, or something else, doesn’t?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Yes, well, one of the themes of The Right is that conservatism is not monolithic, that there are many different conservative groups; many different types of conservatives; many different flavours, if you will, and not all of them fit under the banner of what has come to be known as the American conservative movement. It really begins after the Second World War with the foundation of National Review magazine, the publication of Barry Goldwater’s book Conscience of a Conservative in 1960, and then carries on through the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. And in some ways, still exists today.

There are many figures who identify on the right, that is, they are opposed to the left—they are anti-liberal, both in modern liberalism or progressivism, as it’s sometimes called, and classical liberalism stretching back to John Locke and Thomas Hobbes. I needed to include those voices in my narrative to show not only that conservatism is a many-headed beast, but to say that there’s nothing inevitable about the shape that the right takes at a given moment. And the current American conservative movement, which in many ways, in my view, is influenced by the ideas of classical liberalism, is not the only right on offer.

And we see that today in particular, some of these other rights that do not trace themselves back to classical liberalism, that have differing views of the American Constitution, and the Declaration of Independence, that for most American conservatives are so important. Well, these different rights now are feeling energized and contesting what it means to be on the right today. So, that’s why I use this broader category of the right to title my book, and to talk about all of the various anti-left, anti-liberal thinkers and actors who have populated American political thought and American politics over the last century.

SEAN SPEER: You mentioned, Matt, that your book begins in the early 1920s. What are the key sources of continuity between that era and the present in terms of understanding the American conservative movement?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Yes, I’m so glad you asked this. I think it’s one of the major things I learned while researching the right, which is that in many respects, today’s Republican Party resembles the Republican Party, not of Ronald Reagan, but the Republican Party of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge in the 1920s. And I think this becomes clear, as I explored the history of the 1920s. You look at the Republican Party at that time, it was very reluctant to intervene overseas as a result of American’s experiences in the Great War, in World War One. The party in the 1920s was for immigration restriction, supported the laws that basically ended immigration to the United States for about forty years. The party at the time was for tariff revision, but in principle for a tariff, a protective tariff, to insulate American industry from international competition. And you see analogs to that in the current Republican policies toward not only protective tariffs against China but also this new idea—it’s not really a new idea, it’s a new one for the Republicans—to have an industrial policy of subsidies and protections in order to compete in the global economy.

You also see the importance of religion to Republican identity. You see the texts of President Coolidge in the 1920s linking fidelity to the religion, not any particular religion—this is America so there’s no established church but basically a generalized Protestantism more or less—with national strength. And I think you see that today on the right and in the Republican Party, the importance of religious belief, really emanating from a different sector of American society. In this case, today, the evangelical Christians, self-identified evangelical Christians, powering that linkage between religious piety and national strength.

So, for all these reasons, when I look at the Republican Party today, I see a reversion to what the GOP looked like in the 1920s, and it raises this idea that in fact, perhaps the aberration wasn’t the Trump years. It was the Cold War conservatism that I grew up with, the conservatism of Ronald Reagan and Barry Goldwater, and kind of ending in the George W. Bush presidency. So, it’s very important to understand the connections between today’s Republican Party and this older Republican Party. And that’s one reason why I wanted to widen the horizon of my story, and really start before World War Two and even before the New Deal.

SEAN SPEER: Those are just fascinating insights. Matt. You also write that this one-hundred-year period that the book documents is marked by something of a tension between an elite-driven intellectual and political movement and a more populist political expression represented by figures like Joseph McCarthy, Pat Buchanan, and even Donald Trump.

Let me ask you about the current place of the populism in the American conservative movement. Is contemporary populism something different than these past episodes? If so, what makes it different? And how should we understand the current fit of populism in this broader one-hundred-year context that you cover?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: So, I’ve been fascinated with American populism for many years. A previous book I wrote was about Sarah Palin and the response to her when she became the Republican nominee. I did a lot of writing about the Tea Party phenomenon during Barack Obama’s presidency in the 2010s. And so, as I researched this history of the right, I found that populism is a feature of American politics. That there’s something about our country, its nature, and also the way in which our polity is structured, provides the space for these periodic upsurges of populist sentiment aimed at political elites. And you find that these upsurges of grassroots animosity toward the people in charge often empower Republican elections—empower Republican elites to take the place of the democratic or liberal elites who are who have failed to respond to changing circumstances or simply offered the wrong answers in the view of the electorate, which gives us a populist moment.

I think we’re still living through a populist moment that began, really in the second half of George W. Bush’s second term. So, around 2006-2007. Conditions in the country deteriorated to such a degree, arguments over national identity and the place of immigration in our society grew so intense, and then the responses to the financial crisis, and also, to recurring crises on the border and international terrorism, kind of fueled this ongoing populist upsurge. This latest iteration is now empowered by mainly parents who are extremely upset at what—not only the school closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic—but what they learned about the curriculum in the public schools, from that experience when their children were home with them. And one theme I found is that many of these populist moments are fueled by people rebelling against government and perceived government interference in the raising of children.

And so, if we look at an earlier populist moment in the 1970s, late 1970s, a lot of the same issues surface surrounding the place of schools: where do you go to school, what is taught in the school, the ideas about sex-ed. All of these things tend to really get under the skin of parents, many of them religious and social conservatives, and they drive this populist support. And it’s up to the Republican and conservative elites to not only understand this phenomenon and the sources of populist revolt, but provide realistic solutions that address the conditions driving the revolt. That is something that the modern Republican Party has not been very good at. So for that reason, I expect this populist energy to persist for at least a few more years.

SEAN SPEER: You mentioned in a previous answer the role of National Review in the modern history of American conservatism. Let me take that point up: the magazine in general, and Frank Meyer in particular, provided the intellectual glue to hold the American right together in the form of fusionism in the 1960s. Yet one of the underlying assumptions of contemporary conservative populists that you’ve just described is that fusionism is dead. For our listeners, what is fusionism, and do you, Matt, think it’s reached its expiry date?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: So, the idea of fusionism comes from an argument that took place in the pages of National Review in the early 1960s. And one of National Review magazine’s senior editors at the time was an ex-communist named Frank Meyer, who had been converted, by a reading of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom, to a free-market constitutionalism that he adhered to until his death in 1972. Meyer often made the case that economic conservatives, or what we might call libertarians, are the allies of social conservatives, or what we might call traditionalists. That libertarians and traditionalists are not opposed, that they’re working toward common ends, and that they share a common enemy not only in the Communist Party and in the Soviet Union, but also in the growth of the centralized bureaucratic state at home.

This idea has always been contested. So, a lot of the arguments we’re having over fusionism today are not new to me, and they won’t be new to anyone who reads the right because they’ve been going on for at least 60 years.

And Meyer’s position was lampooned by another National Review editor named Brent Bozell, who was very much on the social religious side of the equation as “fusionist.” He said, “You’re trying to fuse two things that don’t go together.” Well, the name stuck, because Meyer basically said, “Fine, if you want to call me a fusionist, I’m a fusionist.” Meyer believed that American conservatism traces its roots to the American founding, and the American founding took place at a historical moment when libertarians and traditionalists had not separated, right? We are pre-French Revolution in the United States. Our revolution is unique, according to Frank Meyer, and the principles of natural liberty allow not only for free markets but also for a flourishing civil society. So, anchoring conservatism in the Constitution is a very important part of the fusionist idea.

Now there, Meyer tended toward the libertarian side, there’s no question about it. And there are some theoretical issues with his position that Bozell was able to tease out, and they get into this idea of do we always choose the good? How are our moral choices are actually formed? Like many libertarians, Meyer was often very quick to just assume the existence of children, right? That children would just appear at age eighteen ready to be moral agents. So, what roles do families, churches and the state play in character formation—but the government and the law also play a role that Meyer often neglected.

However, despite these intellectual nuances, I think, fundamentally, the fusionist position is alive and well in the Republican Party, and among most conservatives. Most American conservatives don’t worry about whether something works in theory. They’re most concerned about whether it works in practice. What you find when you survey Republicans and you survey self-identified conservatives is that they find no issue with being both religious and supportive of capitalism. The question becomes, what do we mean by capitalism? And does that support for capitalism also mean that in some cases you might have a tariff? Or you might have some type of a welfare policy, income support policy? But in the main, I think, this fusion that one can both be for free markets and competition and choice, and have a belief in a supernatural order, in biblical revelation, a traditional family life—I mean, we see it in a lot of places today. It persists, despite I think, a renewed and reinvigorated challenge from the social and religious right.

SEAN SPEER: You mentioned Meyer’s origins as a communist. Matt, as one of the leading intellectual historians of the American right, I have to ask this question: Why do you think so many of the leading conservative intellectuals of the 1950s and 1960s were formerly communists?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Well, as the title of one collection of ex-communist writings put it, Communism was the God that failed. We forget Marxism’s hold on intellectuals in the latter part of the 19th century and, in particular, the beginning of the 20th century. And even more in particular, during the depression years, when it was largely thought that capitalism and democracy, what we call the liberal democracy now, had failed. So, many people turned toward radical ideas, explanations, and solutions, and the one that was on hand and had been since 1848 was Marxism and Communism. But many of these intellectuals quickly became disillusioned, and it was a question of the shape of their disillusionment that determined where they might fall.

And so, someone like Meyer, who was taken by the libertarian thinker Friedrich Hayek, really moved toward a more libertarian view of things. For another ex-communist who became very important to National Review, Whittaker Chambers, it was a religious conversion. He became convinced that Marxism just didn’t explain that there was a design to the world, that there was something more than sheer atoms in the void, and so he became a much more spiritual thinker.

Then later versions of ex-Marxists who kind of deradicalized from Marxism into a form of Cold War liberalism and were Democrats, well, by the time they get to the late 1960s, and 1970s, many of them, really a few important ones, become Republicans as well. Those are the first wave of neo-conservatives. I think Communism, as Hayek points out in his great essay, “Socialism and the Intellectuals”, it just appeals to a certain type of mind that is intrigued by ideas, that wants to explain politics and economics, and offers not only a library of resources to draw from but also a method of inquiry and debate that’s very appealing to young people in particular. But lucky for those of us on the right, many of these young people eventually find, correctly in my view, that Marxism doesn’t explain everything or much of anything, and in fact, is very self-contradictory. That sets them on the path toward conservatism and the right.

SEAN SPEER: The book documents the lives ideas and writings of so many fascinating figures of 20th century American conservatism, from Albert Jay Nock to Wilmoore Kendall, to Irving Kristol, and of course, Bill Buckley himself. Who, in your view, is the conservative intellectual who is most underappreciated for his or her contribution to the right’s intellectual life?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Well, you know, we’ve mentioned him a few times already, so, he’s not unappreciated in this podcast, but I think it would be Frank Meyer, who was called by Buckley, “air traffic control,” because he really kept everyone at National Review alert to what it meant to be an American conservative, the idea of that adjective doing a lot of work. And I think it is often forgotten today because he died at a relatively early age. He died in 1972 of cancer, and so I think his legacy is not fully appreciated. But I’m happy to know that there are actually a few biographies of him in the works.

Another thinker who really was one of my ways into writing The Right was James Burnham, another ex-Marxist, who became very influential in National Review for many decades, though Burnham has found kind of a revival in recent years among many on the so-called New Right, or the newest right. I think they get him wrong in a lot of ways, and I think they are reading Burnham through one of Burnham’s main interpreters, a paleo-conservative writer named Samuel Francis. But nonetheless, Burnham was very important to this history. Buckley called Burnham the most important intellectual influence on National Review, and to the degree that National Review really was the site of American conservative intellectual activity for several decades, I think that’s a pretty high commendation.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s move forward a bit closer to the present. How does Newt Gingrich and The Contract with America fit in your narrative? Was it a continuation of Reaganite politics? Or in hindsight, was it more disjunctive? Did it have more in common with today’s populism? Are we, in effect, living in the world that Newt created?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Yeah, a lot of people say that. Here’s the way I think of it. I think the way into thinking about the 1990s and conservatism is to start with Bill Clinton. And in my view, and as I discussed in The Right, Clinton consolidated the Reagan legacy from the perspective of a 20th-century conservative. The policy results of the last six years of Bill Clinton’s presidency were really good. Here we’re talking about a guy who signed into law the North American Free Trade Agreement; the guy who signed into law welfare reform; the guy cut capital gains tax rates; he presided over a balanced budget agreement. He was prepared to introduce personal accounts into Social Security but for the Monica Lewinsky scandal in 1998. I think Clinton is, in some ways, the dominant conservative figure—small “c”—of the late 1990s.

How does Gingrich fit in? Well, Gingrich has gone through many different personas in his decades-long political career. He’s always been very interested in futurism—the idea that technological innovation will improve American life, and that American economic dynamism is the fuel for technical innovation. That puts him on the American right in that sense. Gingrich really was responsible for ideologizing the Republican Party by making it take a stance against the entrenched House leadership. You know, by the time that the Republicans win Congress in 1994, the House had been controlled by the Democrats for 40 years.

So, Gingrich goes after corruption, public corruption, and that is a very populist trope. But he’s also talking about how Zero-G health innovation and space will revolutionize medicine and the life of people with disabilities, and that almost sci-fi quality. That’s to me the real Newt. That’s really why he wakes up in the morning and gets involved in politics. But he was able to incorporate some Reaganite ideas. He was also very interested in identifying the sources of popular discontent during the first two liberal years of the Clinton presidency. He is the man, I think, most responsible for the Republican takeover of Congress in 1994.

However, once he got in charge, once he becomes Speaker of the House, his strategic vision does not translate into tactical victories. And so, Clinton very carefully and cleverly basically stole the Republicans’ thunder, which led to all those public policy results I mentioned earlier, but infuriated Republicans because what they’d look up and Clinton had beaten them once again.

SEAN SPEER: Your observations about Gingrich’s futurism are a good segue into a question that I’ve wanted to ask you since we scheduled this interview.

In March 2020, the George Mason University economist Tyler Cowen was interviewing New York Times columnist Ross Douthat on his podcast, and he asked Douthat whether he agreed that Peter Thiel, the Silicon Valley investor, was the most important public intellectual on the right. Douthat instantly said he mostly agreed. The question, and the answer, surprised me. I hadn’t thought of Thiel as a public intellectual or even someone on the right.

What do you think of Thiel as a conservative figure? How does his set of ideas fit in the current moment of the intellectual ferment?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: I do mention Peter Thiel in The Right. I talk about him and how he fits into the present shape of American politics and American conservative and right-oriented thought. You know, Peter Thiel, the tech entrepreneur, has only given us a few clues as to his actual beliefs. He did become the first out gay man to speak to a Republican convention in 2016, and that speech I recommend to many people as a kind of an outline of his worldview. He co-wrote the book Zero to One, actually with the Senate candidate in Arizona who he is funding, Blake Masters, his former student and employee. Basically, Thiel believes that globalization has led to a stagnation in American innovation, a stagnation in our politics, and he’s very interested in correcting that, in basically overthrowing the applecart with the idea that if you disrupt everything politically, then perhaps technological progress could resume.

So Thiel supported Donald Trump’s insurgent candidacy in 2016, and was slightly less supportive in 2020, I think, much to Trump’s chagrin. And he has supported many of the institutions, scholars, and politicians associated with this New Right with this idea that the American right has too many connections to classical liberalism, that the libertarian-traditionalist fusion is no longer operative, and that conservatives, who might not even call themselves conservatives, they might better refer to themselves as counter-revolutionaries, or insurgents, should try seize state power and direct it for conservative ends. Thiel has been supportive of many of the figures in this movement.

I don’t know if I would say he’s the most important public intellectual on the American right today. I would say, he’s certainly among the most important right-wing philanthropists alive today. And the kind of a seeder of ideas, a funder of ideas, in the same way that he was a funder of start-up companies.

SEAN SPEER: As we look ahead at the state of American conservatism, there are different factions making a claim for its centre of gravity. There are the post-liberals or the New Right, as you mentioned, who may be best represented by the group who organized and recently participated in the second national conservatism conference in Orlando. But the pandemic has also exposed a strong strain of folk libertarianism on the right, which has been called by some Barstool conservatism after the irreverent and popular sports website. These groups may share in their disdain for cancel culture, and other aspects of elite culture, but they obviously have quite different values and preferences.

How should we think about the current intellectual battle for American conservatism? What are some of the different paths that it may go down? And in your view, Matt, does any particular persuasion have a current advantage in defining the future of American conservatism?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Sean, I think it’s very hard to tell. I have a lot of concerns, and not only with some of the ideas that are being put forward today on the right, but also with the idea that somehow these ideas are connected to what’s actually happening in the Republican Party. I think it’s interesting that many of the figures on this New Right are really linked by their support for Donald Trump. And yet, if you asked President Trump about some of their ideas, I think he would kind of like blanche and say, “What are you talking about” right? In fact, when you look at the Trump presidency, those four years in office, Trump achieved some long-standing conservative goals.

Some of the things that people call “Zombie Reaganism”: he had a tax reform; he swung the Supreme Court to originalism; he increased the defense budget; he opened the Arctic National Wildlife Reserve to oil drilling, something that conservatives had wanted for forty years. It’s not like he spent his four years instituting the blue laws, right, preventing commerce on Sundays. In fact, I don’t think he’d want to.

I’ve always found that odd. I think there’s no question that Donald Trump remains the most important Republican in the country, and there’s no question in my mind that he changed the character of the Republican Party, its personality, its demeanor in ways that actually I had doubted he would do. I thought he was such a unique personality that he wouldn’t have that effect, but I realized I was wrong.

I think there’s no question he did modify the GOP on some major issues. For example immigration. Very few Republicans now openly discuss an amnesty of illegal immigrants in the United States anymore, which pre-Trump half the party was willing to do. Very few Republicans bring up entitlement reform, and those that do, like Senator Rick Scott from Florida who included it in his recent proposal for a GOP agenda, were kind of swatted down. The idea of China as a competitor, and as a real threat in the 21st century that’s kind of President Trump, he forced the party into that position. It’s not clear to me that that’s necessarily what the figures on the New Right are talking about. Obviously, it has some commonalities with them, but it’s not quite the full-on rejection of classical liberalism and the reassertion of religion in terms of our politics that you see in some of those corners. So, I view a lot of this debate very skeptically.

For me, I’m most interested in what do Republicans believe, and because one of the lessons from writing my book, The Right, is that we have to draw distinctions between the Republican Party and the conservative movement. And we have to draw distinctions between the conservative movement and the conservative intellectuals, or the right intellectuals. And that third group, the intellectuals, they’re the smallest group, and they’re also the least influential, right? That takes many decades for their ideas to have an impact because there’s contingency involved. They have to be connected to institutions, and then they need to convince political actors.

Another reason why I am I’m often cautious in answering this type of question is it’s very hard to know which ideas will have a great effect down the road. I do think, especially among younger people today, there is a great deal of interest in what the New Right is saying. The question is, is that an intellectual fad? About 10 years ago, there was a great interest in what the libertarian right was saying, and what Ron and Rand Paul were saying. Not so much interest anymore. Now, there’s a great interest in what the New Right is saying. Is that going to be the case in 10 years? I don’t know it may be, but I think there are other factors that may militate against it.

SEAN SPEER: Matt, I am sensitive of your time. If I can just ask two final questions. The first is that one of the long-standing tensions within the American Conservative intellectual movement is whether the goal ought to be to infuse conservative ideas into mainstream institutions or create an alternative ecosystem. Jonah Goldberg often argues, for instance, that conservatism and the country would be better off if there were more conservatives at Harvard than if there was another Hillsdale College.

What do you think about this tension and the proper goal for contemporary conservatives?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: I think, ideally, a strategy of permeation would be the most effective. Conservatism was meant to create a counter-elite to the liberal elites who came into power with Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, and there have been mechanisms that have helped create counter-elites, certainly in media and in the legal profession. But many of those mechanisms ended up being counter-institutions that were created, or that were used to kind of provide a home for conservatives as they ascend through the more mainstream institutions.

I think of the Federalist Society as perhaps the most effective conservative institution of the last fifty years. It was formed in 1982, so it’s forty years old. Talk radio is a counter-institution to the mainstream media: extremely successful, very popular. So, I think ideally, that they would work together with the strategy of permeation, and then the strategy of building counter-institutions, but they seem to have come apart lately.

It’s also hard to have a conservative at Harvard if Harvard won’t let any conservatives in. Professor Mansfield is still there. They’re a few others. Actually, one of the New Right thinkers, Adrian Vermeule, amazingly to me is a tenured law professor. Liberalism worked out for him there. So, we’re often forced as conservatives to build these counter-institutions, and I do think they could do some good. I’m talking to you today from my office at the American Enterprise Institute. At its best, AEI serves as a home for thinkers who can’t find purchase in liberal institutions and is able to provide the space and the resources for them to develop their ideas. So, I do think we shouldn’t just shun counter-institutions. We should also try to permeate the existing mainstream institutions to the best of our ability.

SEAN SPEER: Let’s wrap up with a final question. It speaks to a point you made earlier about the importance that the adjective American plays in the phrase American conservatism. Do you want to just elaborate a bit on this idea that American conservative ideas are particularistic. This is especially important for a Canadian audience, that, of course, draws a lot of intellectual sustenance from the American conservative debates, but obviously finds limits in the kind of translation of those ideas, particularly as they manifest themselves in politics when it comes to our own intellectual and political debates?

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Well, I think it was Samuel Huntington who first really pointed out in an article in the 1950s that conservatism always requires an adjective to modify it. Because conservatism means very different things under very different circumstances. For most people, they think conservative, they think Edmund Burke. Edmund Burke, a Whig, actually a reformer, in England, in the late 18th century opposing the French Revolution. And then in the post-revolutionary period, the movements of reaction are thought of as the great examples of conservatism in the 19th-century. European conservatism standing for the defense of established institutions. And those institutions in the European context were the established church, the monarchy, and the aristocracy, the nobility. Well, in an American context, we don’t have an established church, we don’t have a king, and we don’t have a title of nobility, okay? Everybody has a class system, but we don’t have baronesses and barons and lords and viscounts and such, right?

So, what does it mean to be an American conservative? I think it means a defence of the particular American institutions and those institutions we traced to the founding of the United States: the Declaration of Independence; the Constitution; the political thought of the Constitution, which is expressed in the Federalist and the Federalist Papers. The political tradition that emanates from those documents and the system they established. That’s what I think American conservatives ought to defend. And that means that American conservatism is going to be more small “l” liberal, have a larger place for freedom in it because of the nature of that tradition. It’s also going to mean that American conservatism will be more populist than many other forms of conservatism. Just as we were saying earlier in our conversation, that there seems to be this link between populist energy and the American political system. You can’t divorce the two.

The question is, are you able to internalize popular sentiment and respond to it concretely in a good way, rather than follow it down rabbit holes of scapegoating and conspiracy theory? These are the things that make American conservative thought American. And one of the lessons of my book is that people on the right in the United States should embrace that identity and should understand that and recall the tradition. And when we do that, we learn that there’s nothing new under the sun. It’s all been said before, and that should give us I think, hope for the future.

SEAN SPEER: Well, for those who need to relearn and recommit themselves to that tradition, there’ll be well served by reading The Right: The Hundred-Year War for American Conservatism. Matt Continetti, thank you so much for taking the time to speak to us today at Hub Dialogues.

MATTHEW CONTINETTI: Thank you, Sean.